|

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

THAT THE PAST SHALL LIVE... the history program of the National Park Service |

|

MISSION 66 a bold new program for the parks

"... to stop time at a great moment in history so as to cause men busy about present things to pause and look with understanding into the past . . ."

Briefly stated, this is the basic objective of the National Park Service in administering the priceless historical heritage entrusted to its care.

This objective is stated somewhat more formally in the National Park Act of 1916 which declares that the fundamental purpose of the Service is to "conserve the scenery, and the natural and historic objects and the wildlife" in the areas comprising the National Park System, and to "provide for the enjoyment of the same in such a manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations."

Accordingly, the Park Service, since its establishment, has sought to accomplish two ends in each historic site:

First, to preserve the site and its historic structures and objects and where possible and feasible to restore the scene as it was at the time of the area's greatest significance, and,

Second, to so administer and develop the area that it would provide the greatest possible spiritual refreshment, inspiration, and enjoyment to the people of the United States.

But in the decade and a half following the outbreak of World War II, work toward these ends became all but impossible. During the war years, the pressing demands of national defense placed the national parks virtually on a stand-by basis, and appropriations in subsequent years were not large enough to make up for lost ground. The meager funds available had to be thinly spread to cover only the most urgent emergency needs, and as a result not only the historical areas but the entire Park System fell into a state of dangerous disrepair.

To meet this growing threat, the National Park Service, in 1955, decided upon a dramatic new approach.

It drew up a list of the physical improvements, staff increases, and additional lands and operating procedures that would be needed to give the American people the kind of National Park System they deserve and have a right to expect.

By mid-1956 this planning had been completed and incorporated into a bold new program known as MISSION 66.

Vigorously endorsed by the Secretary of the Interior, and President Eisenhower, the program—designed to produce a "model" park system by 1966—won the immediate approval of the Congress and, with adequate new appropriations thus assured, work was begun on one of the most far-reaching park conservation and improvement programs ever undertaken in this country, or elsewhere in the world.

Under MISSION 66, exciting new developments are taking place throughout the far-flung chain of historic and prehistoric areas linked within America's great National Park System.

In all of these developments there is one basic, overriding aim: to turn back the pages of time and establish a vital relationship between the visitor and the memorialized people and events. To the Park Service, this goal is only successfully achieved when the prehistoric ruin, for example, somehow manages to convey the feeling in the visitor that the ancients who lived there might come back this very night and renew possession.

These things, then, are being done under the MISSION 66 program to help bring about this feeling of living history:

Historic buildings are being rehabilitated, refurbished, and restored.

New Visitor Centers are being built and modern museum exhibits prepared to help recreate the atmosphere and mood of the time or event commemorated in the historic site or shrine.

New lands are being acquired whenever possible to prevent or eliminate jarring intrusions on the historic scene.

Civil War sites are being developed so that fitting observances may be held at each as its centennial occurs in the years 1961 to 1965.

Archeologists, historians, architects are at work delving more deeply into the historic past, and already their findings in numerous areas throughout the System have thrown important new light on the nation's origin and growth.

New markers, new trailside exhibits, new interpretive publications—these and many other products and activities are facets of the "re-awakening of history" under MISSION 66 in the sites and shrines which form so important a part of the National Park System.

a few examples of the 'Reawakening of History'

SOME idea of the scope of what is taking place throughout America in this vigorous new program can probably best be given by citing a few examples of the types of projects being undertaken.

One of the most interesting is the work of developing Independence National Historical Park in Philadelphia.

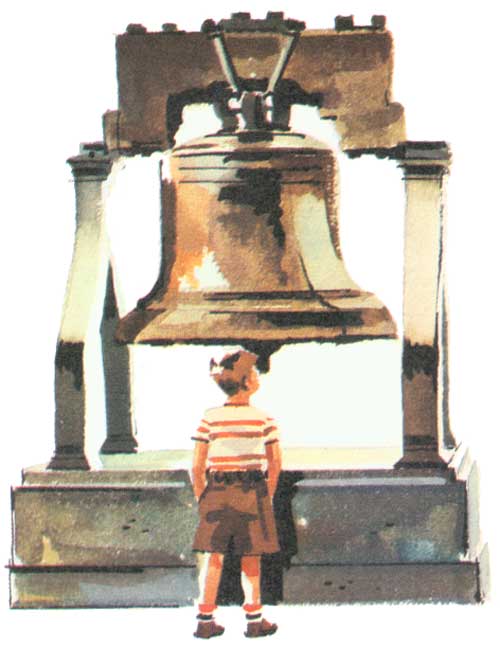

There the Liberty Bell and Independence Hall form the core of a unique undertaking designed to preserve for all time the cradle of American independence.

This colossal project is a joint venture in which the nation, the State, the city, and private agencies are linked in partnership. It has as its goal the development of a dignified and park-like setting for Independence Hall in those few blocks of Old Philadelphia where more significant history took place than anywhere else in America.

Announcement of plans for the project captured the imagination of patriotic citizens all over America. Some idea of the enthusiastic support engendered may be gathered from the fact that the General Federation of Women's Clubs raised nearly a quarter of a million dollars to finance the restoration and refurnishing of the Hall's first floor as it was when the Declaration of Independence was signed and work on the Constitution was completed.

Here many thousands have had the memorable experience of witnessing the process of time being turned backward to recapture stirring moments of the nation's early history as they watched the skillful hands of artisans restoring the old assembly hall to its original state, as they saw the old park-like setting of the area being recreated in the ancient streets.

This is only one example of the broad restoration program. Elsewhere many other historic buildings are being rehabilitated and reconstructed. These include such places as the old tavern and jail at Appomattox; the historic Beauregard House on the ground where the Battle of New Orleans was fought; the home built in 1777 by the American Revolutionary hero, General Philip Schuyler, in Saratoga National Historical Park; the frontier military buildings of Fort Laramie and Fort Union; and many others. In each, the visitor is being helped to relive history through being able to see places and things as they actually were at the moment when they were touched by the finger of destiny.

And here, too, in the presentation of these and other historic sites—in such places as the Adams Home in Massachusetts, Arlington, the Vanderbilt Mansion at Hyde Park, N. Y.—the efforts to bring the past alive do not stop with simply installing the furnishings and objects of the times. Instead, every possible effort is made to make the visitor feel that the occupants may return and take up living there at any moment.

This process is graphically described in an incident related by the noted author, Freeman Tilden, in his book entitled "Interpreting Our Heritage."

"On a Sunday afternoon," he writes, "I went to the Custis-Lee Mansion, 'Arlington House,' just across the Potomac from Washington. As I entered, somebody was playing the piano. It seemed so perfectly natural that somebody would be playing a piano in a house that had sheltered the Custises and the Lees, or indeed in any historic house where people had lived! I had been many times in this famous home and had delighted in its beautiful maintenance. I had, in truth, never actually felt it to be cold; but like so many other precious relics of the past, its treasures have to be safeguarded, and most of the rooms can be seen only from their doorways. That is a penalty we must pay for preservation.

"But now, I felt that this house was peopled. Not by visitors like myself, but by those who had best right there—the men and women who loved the place because it was home. In a drawing room an attractive girl, costumed in the period of 1860, was playing the very tunes that were current at that time. It could have been a neighbor lass of Miss Mary Custis at the instrument, which itself was of the very period. There was nothing obtrusive about the music, and I noted with pleasure that most of the visitors were not curious about it, a sure sign that it was in perfect harmony and accepted as part of the recreation."

Thus the Park Service is engaged in an unending search for truth—and reality—in its presentations.

This search extends to the careful and painstaking studies and excavations of archeologists, historians, and architects working jointly and separately in MISSION 66 projects designed to insure the authenticity and accuracy of the stories of history and prehistory spread before the millions of visitors to the Park System's sites and shrines.

important new facets of history are being brought to light

AS a result of this work, piece by piece, important new facets of early times on this continent are being brought to light.

These are a few of the significant discoveries:

A recent study provided a fully documented record of the exact appearance of Fort McHenry as it appeared in 1814, and of the events of the Battle of Baltimore that swirled around it. This study showed a number of marked differences between the fort as it was during the historic British shelling throughout the night of September 14, 1814, and the reconstructed fort of today; placed the defense against the attack on Baltimore in its true perspective; and made it possible for the first time for the Park Service to present a fully accurate account of the events of that stirring moment in history. But perhaps the most exciting find at Fort McHenry was the discovery of what is believed to be the actual site of the flagpole from which Old Glory flew throughout the bombardment, thus inspiring Francis Scott Key to the composition of the words of our National Anthem. By this discovery a mystery that had lasted for nearly a century and a half was solved.

In Alaska, in another project, the exact location of the fort where the Sitka Indians made their last heroic stand against the Russians in 1804 was brought to light after more than 150 years, when remains of the heavy log fortification were found in what is now Sitka National Monument on Baranof Island.

In the Painted Rock Reservoir area of southern Arizona, a thousand-year-old Mexican-type platform mound was unearthed—the first structure of this type found in the American Southwest, and a find which helped to answer long-standing questions as to the origins of the early culture of that area.

In Yorktown Battlefield, Park Service archeologists working with historians uncovered the remains of historic "Redoubt No. 10" in which Washington received and signed the articles of Cornwallis' surrender.

These are a few of the projects, and a few of the significant discoveries. There are many others. The unearthing of the long-buried parade ground and 12 original gun rooms of historic Fort Sumter in Charleston harbor. The exploration of rugged new areas in the Mesa Verde and the excavation of important ruins known to be located there. In all parts of America, the work of reclaiming new and fascinating details of history from the past goes on.

And closely linked with this is the ever-developing program of presenting to the American people—in the clearest and most meaningful manner possible—the lessons and inspiration of their own story of this continent.

One of the most important contributions of MISSION 66 to the interpretive program of the National Park Service is the provision of modern, well-equipped Visitor Centers as the focal point for the re-creation of a living moment in history or prehistory. Visitors to many areas—such sites as Yorktown and Jamestown in Virginia, Fort Frederica in Georgia, and Fort Caroline in Florida—have already seen how these Centers serve to provide a ready understanding of the meaning and significance of what they have come to see. Other such Centers are planned or under construction in other areas. All together, more than 100 are scheduled for construction in the 10-year course of MISSION 66.

The Visitor Center is the key to the entire information and public service program for a park. It provides such things as publications, maps, exhibits, and it is staffed with uniformed personnel to provide the visitor with authentic information about the things they want to know. All of these things combine to bring the story of a particular time or event clearly into focus. But actually the Visitor Center does much more than this. It is designed to re-create within itself, insofar as possible, a portion of the past.

An outstanding example of what this means may be found by the visitor to Dinosaur National Monument, parts of which are located in Utah and Colorado. In the Utah section, at the famed Dinosaur Quarry, the new Visitor Center has been constructed against the face of the ridge where exposed fossil-bearing strata show huge dinosaur bones in high relief. From an 180-foot paralleling gallery, visitors may see and study the fossilized remains of the prehistoric monsters in strata deposited millions of years ago. They also may watch paleontologists continuing the work of reliefing dinosaur bones and preparing specimens. Here, then, as in many other places in the System, it is not in the least difficult for the visitor to "feel" the story of the past.

in many ways, the past is brought to life

OUTSIDE the Visitor Centers, markers and trails, displays and modern audio devices take up the story and provide even further details as one walks the earth on which history was made. Heroic paintings—such as those at Jamestown—help to re-create the scene. Carefully placed markers locate the exact site of some lost landmark, or assist in following the course and flow of history in that spot. At the Liberty Bell, at Jamestown, and in other places the visitor's sense of reliving history is stimulated, too, through stirring messages relating to the bygone time, recorded and available at the press of a button for any who would listen—and many do. Great dioramas depicting scenes of pioneer and prehistoric life; museum exhibits containing articles intimately associated with the daily lives of our forebears on this continent; new publications, including an important series of Historical Handbooks providing absorbing, penetrating studies of significant sites and areas and times—these and many other methods and techniques are being used in increasing volume under MISSION 66 to satisfy the need of growing millions of Americans for a closer, more personal association with their inspiring past.

Of course, the very earth itself in these hallowed places is of importance. For example, the student of military history can fully comprehend the ebb and flow of battle—the troop dispositions, the tactical maneuvers—only by studying the actual topographical conditions of the battlefield. To enable those interested to grasp the character and course of military operations, the National Park Service preserves as nearly as possible the physical conditions prevailing at the time of battle; stabilizes existing remains of fortifications, trenches, and earthworks; makes sample restorations when they will help in the visualization of the scene; and maintains museums for the display of weapons and other objects used in battle.

This is one way in which participation is provided for the visitor. Moving over the rolling fields of Gettysburg, for example, with its reconstruction of the historic scene, he can easily imagine himself a part of, or at least a witness to, that climactic clash of arms.

Wherever possible, this sense of participation is provided in another way—through authentic demonstrations that re-create specific facets or functions of the past.

To illustrate, few people can look at pictures and read a description of a water-driven gristmill and actually visualize how grain is made into flour between revolving stones. But on the Blue Ridge Parkway or in Rock Creek Park in Washington, D C., visitors can see such mills in operation, grinding out flour just as it was done generations ago. Similarly, visitors to the Craft Center at Moses H. Cone Memorial Park on the Blue Ridge Parkway can see weavers at work making cloth just as their pioneer ancestors did.

At Jamestown, visitors can witness demonstrations of handmade glassmaking in a glasshouse patterned after the Jamestown Glasshouse of 1608, at the place where the Jamestown colonists first produced glass in their effort to find a profitable commodity in their new American home. At Mesa Verde, Navajo Indians help to recreate the historic past by taking part in colorful, ancient tribal dances.

No book, no series of photographs or drawings can speak as convincingly of the way of life of our forebears as these demonstrations in which the visitor experiences an active sense of participation in the past. Freeman Tilden describes this sensation most eloquently when he writes of a park visitor: "I am quite sure that when he takes the barge ride on the old C&O canal, in our National Capital Parks, he feels the distinct pleasure of reverting to a period that has long gone. He sees the mules tugging at the towrope, and passing through the locks can easily imagine himself a traveler to Cumberland, taking his ease on deck and greeting his neighbors at the halting places."

These are but a few of the stimulating experiences awaiting Americans today in the historical and archeological areas of the National Park System.

Other plans, other programs, other projects are being evolved day by day as MISSION 66 moves forward into full development.

All of these developments have a cogent meaning for every school child, writer, artist, educator, student—every American. They will be carried on through 1966 until all essential work is completed—and until each site and building will form a link in a living chain of history in which every citizen can take the deepest sort of pride.

public use is expanding at an unprecedented rate

IN response to this bold new program, public appreciation and use of the places of historic value in the National Park System is expanding at an unprecedented rate.

Ten years ago, less than 10,000,000 people visited the System's hallowed sites and shrines. In 1958, this figure had more than doubled. By 1966, according to present estimates, the total is expected to rise to 35,000,000 or more.

A striking demonstration of the deep and growing interest of Americans in the places and events associated with their past was given during 1957 when more than 2,000,000 persons were drawn to one park area to witness and participate in one special historical event. The place was Colonial National Historical Park, and the event was the Jamestown, Williamsburg, Yorktown celebration commemorating the 350th anniversary of the founding of the first permanent English settlement in the New World at Jamestown in 1607, the flowering of Virginia culture and statesmanship at Williamsburg on the eve of and during the Revolution, and the final winning of American independence at Yorktown in 1781. The celebration was marked by the opening of new Visitor Centers and museums at Jamestown and Yorktown, by the visit of Queen Elizabeth II and many other distinguished personages to Jamestown and Williamsburg, and by the reenactment of the siege of Yorktown and the surrender of Cornwallis. The State of Virginia cooperated by building replicas of the three ships that brought the first colonists to Jamestown and by reconstructing a full-scale replica of James Fort at Glasshouse Point.

A striking spectacle, to be sure. But it was something deeper than the spectacle itself that attracted more than 2,000,000 Americans to link themselves personally with those great events of the nation's past.

Certainly it is nothing in the nature of a spectacle that brings literally hundreds upon hundreds of thousands of school children to Washington each year to visit and stand in reverence before the historic buildings and hallowed shrines of the nation's capital.

Nor is there a spectacle atmosphere in the pilgrimages made by millions of individuals and family groups each year to the scores of historic sites and shrines located in every section of America.

These people do not come for spectacles. They come to learn. This is evidenced by the fact that they request, and use, more than 4,000,000 pieces of instructive literature in a year to help them know more about their history and their parks.

And they come to feel.

The American today is kept uncomfortably aware of the challenges to our way of life. Living with these threats, he has a deep desire to understand more fully the meaning and roots of American democracy, to grasp it more firmly so that he can not only cherish, but help defend it.

Because of this he is appreciative of the fuller depth of meaning being provided for him in the historical parks through the vigorous new program known as MISSION 66—and he is demonstrating this appreciation through an ever-growing use of these priceless treasures of our heritage.

America's historic places are facing a grave crisis

FOR the sake of preserving this rich legacy, the strong upsurge of public appreciation and understanding of our historic sites and shrines could not have come at a more opportune time in our national development.

Because, paradoxically, at this time of their greatest popularity, many of America's irreplaceable historic places and buildings are facing their greatest crisis. From one border to another, they are being threatened with impairment and destruction on an unprecedented scale. Problems of many sorts beset them, problems large and small which must be solved if a significant portion of this rich heritage is to be passed on unimpaired to future generations.

The greatest threat, of course, results from our rapid population growth and the almost awesome mushrooming of urban development.

Everywhere across the land this swelling tide of people is demanding more living space—more subdivisions, more freeways, more supermarkets, more reservoirs, more pipelines, more parking lots, more irrigated land.

The public officials and private entrepreneurs who must meet these demands are understandably impatient with anything which stands in their way—particularly if those things happen to be old buildings or "worthless" historic or prehistoric sites.

The result—for those who feel that some of the old values of our nation deserve consideration with the new—is little short of appalling.

At Gettysburg, for instance, artillery pieces placed in the positions of original batteries now point into the kitchen doors of subdivision homes. And this is only one of many hallowed spots where modern developments—often garish and unsightly—have moved ever closer on adjacent lands to mar or destroy the meaning of the historic scene.

Along the Missouri River the habitation sites of five prehistoric civilizations have been sacrificed to the advance of modern progress, disappearing beneath the artificial lake created by new flood-control dams.

On Staten Island, New York, we find a striking example of the accelerating rate of obliteration of the historic past. Before the year 1809, records show that a total of 477 structures were erected there. In 1919—110 years later—one out of four of these buildings was still standing. But in the next 30 years all but some 50 or so of the original 477 had disappeared. At the present rate of demolition, all will be gone 10 years from now.

Many other examples could be cited. Few people fully realize the swiftness with which this trend toward severing our links with the past has been developing within the last brief span of years, nor the total cost in cultural losses that has been the end result. Unfortunately, those who advocate or endorse the spoiling or destruction of a single historic site that stands in the way of a particular new subdivision or commercial development have no way of observing the cumulative effect of the many thousands of such actions across the country.

Of course, no one maintains that every old house, every ancient Indian village site, or every rotting sailing vessel should be saved. Admittedly, many of the 100,000 or more historic places in this country are not as important as the new schools, new shopping centers, and new highways which will replace them. But many thousands of these sites and buildings do have something to say to the present and the future. They do throw light upon our history and the development of our culture. They do bring history to life by presenting the only possible authentic environment.

The nation cannot afford to lose its buildings, sites, objects, or environments of substantial historical or cultural importance.

saving our historic sites is a tremendous undertaking

OBVIOUSLY, the task of saving our most valuable historic sites is a tremendous undertaking, requiring skillful direction, imaginative planning, determination—and money.

In recent years the American people—with their growing realization and appreciation of the value of their historical heritage—have called on the Federal Government to take a larger part in the preservation of historic sites. Cities and States and private historical societies have in many cases turned to the Government for help in expanding their conservation programs. Since 1950, an average of some 70 sites each year has been recommended for establishment as units of the National Park System.

Clearly, the Federal Government cannot undertake historical preservation on such a scale. Yet demands for additional national historic sites and monuments continue to increase. And important places of national significance continue to disappear.

Today, under MISSION 66, the National Park Service of the Department of the Interior is moving forward on many fronts to meet and cope with the numerous problems besetting and threatening the nation's historic values.

For example, larger staffs are making it possible to give better protection to many sites threatened with serious harm as a result of the great upsurge in public use. Before MISSION 66 was launched, some of the fragile and irreplaceable Indian ruins in the Southwest were being rapidly worn away by "human erosion" resulting from too many people tramping the same floor areas and crowding against ancient, weakened walls. The same was true of many of the historic old homes in the East and South. Now, with additional personnel, the Park Service is able to reduce such wear through better guidance and supervision of visitors.

With larger funds and the granting of needed legislative authority, progress is being made in combatting the threat posed by unsightly developments and other types of encroachments on the historic settings of the nation's great places of history. Where possible, the Service is now providing the landscape treatments, or acquiring lands, needed to correct such situations.

MISSION 66 has made it possible, too, to resume work on the long-dormant National Survey of Historic Sites and Buildings. The purpose of this study—begun in the 1930's but suspended since the beginning of World War II—is to identify the nation's most significant places of history and prehistory so that they may be watched over and protected in case of threatened destruction. Rapid progress is now being made in this important work.

A second suspended study now resumed is the Historic American Buildings Survey, which too will go far in the preservation of the nation's outstanding historic values. A joint undertaking of the American Institute of Architects, the Library of Congress, and the National Park Service, the Survey is in effect a national plan for making and preserving records of existing significant structures in the United States and its possessions. Under it, all architecturally important structures in the nation will be inventoried, with the primary aim of conserving our national resources in historic architecture. A secondary purpose is to provide a service to the public by making available exact records, through measured drawings and photographs, of this cultural background of American history.

Another important conservation project being carried forward under MISSION 66 is the Inter-Agency Archeological Salvage Program. Sponsored and coordinated by the National Park Service, this large-scale cooperative enterprise is designed to salvage as much information as possible from the many and varied archeological, historical, and paleontological remains which are disappearing beneath the waters impounded by giant reservoir and flood-control projects. Already, the scientific results of this program have been impressive. From it have come many valuable contributions to the sum of knowledge of the history of man on this continent which otherwise would have been forever lost.

the Federal Government cannot carry the burden alone

A significant feature of the archeological salvage program has been the cooperation of private power companies and pipeline construction firms in financing the salvage of archeological values threatened by their construction projects. These private interests have realized—as a result of explanatory conferences with the Park Service—what is probably the most important fact concerned with all of the efforts to save as much as possible of our rapidly diminishing historical heritage.

That fact is simply this:

The Federal Government alone cannot carry the entire burden of saving from destruction the most significant portions of our historic past.

To hold any hope of success, this gigantic undertaking must be a joint venture in which Federal, State and local agencies—as well as patriotic private individuals and organizations—work as partners.

This basic fact was recognized by Congress when, in 1949, it chartered the National Trust for Historic Preservation, an independent, non-government organization created for the specific purpose of encouraging public participation in the conservation of America's historical resources.

Supported entirely by the bequests and donations of individuals, groups, and organizations with a sympathetic interest in the preservation of the American way of life, this voluntary agency has already been given several properties and is encouraging and aiding numerous other historical conservation projects throughout the nation.

But with wider public knowledge of its existence—and broader understanding of its operations, aims and methods—a great deal more can be accomplished.

Under MISSION 66, the National Park Service is working closely with the National Trust, and seeking in every way possible to assist in generating a wider base of public support for its vital work in preserving our cherished links with the past.

At the same time, the Service is devoting time and energy to the encouragement of other State and local historical conservation programs. Within the limits of available personnel and funds, its advice and assistance are available to conservation groups and agencies and local governments wherever needed in the preservation and administration of historic sites.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

that-the-past-shall-live/sec9.htm

Last Updated: 15-Sep-2011