|

TUMACACORI

Guidebook 1940 |

|

Tumacacori NATIONAL MONUMENT

AMID the semiarid deserts of northern Mexico and southern Arizona lie long, green river valleys, astonishing in their fertility. Up through these valleys came the slow but steady advance guard of Spanish civilization, building missions and establishing presidios, or fortified walled towns, among the Indian natives.

The mission of San Jose de Tumacacori, which lies in the verdant Santa Cruz River Valley of southern Arizona, was one of these outposts of Spanish exploration. Established in 1691 by Father Kino, it was the Spaniards' answer to the request of the Indian village of Tumacacori for the establishment of a mission.

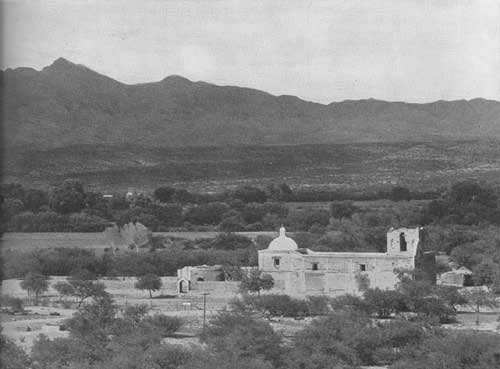

Near the present mission, between the highway and the Santa Cruz River, lies the site of the old Indian village, marked by tall old cottonwood trees. The name Tumacacori, meaning "slanting rocks," is still given to the range of mountains west of the mission, while to the east rises the purple head of San Cayetano Mountain, with the Santa Ritas to the northeast.

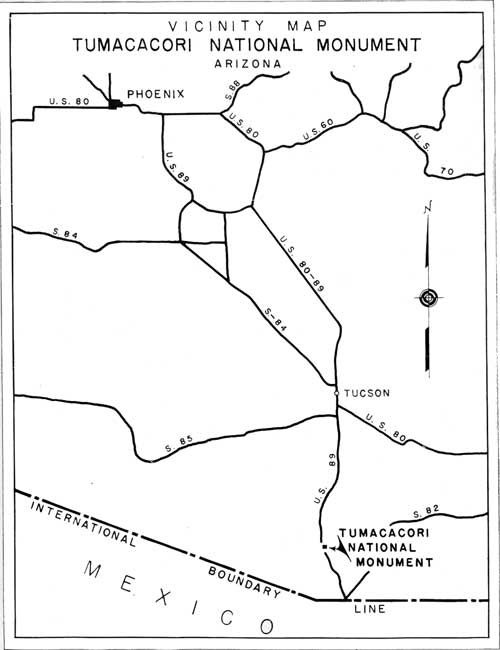

Situated on U. S. Highway 89, less than 50 miles south of Tucson and about 18 miles north of the Mexican border, Tumacacori is still on a principal artery of north-south travel, just as it was in Spanish colonial times.

Tumacacori National Monument has been under Federal Government protection since 1908 when it was proclaimed a national monument. Today, as one of the Southwestern National Monuments it is administered by the National Park Service of the Department of the Interior, with a custodian in immediate charge, whose address is Box 797, Nogales, Arizona.

A guide fee of 25 cents is charged each person, except children 16 years of age, or under, or groups of school children 18 years of age, or under, when accompanied by adults assuming responsibility for their safety and conduct.

Ruins of a structure east of the cemetery wall, believed to have been a dormitory. According to Indian tradition it was a convent |

MISSIONARIES IN PIMERIA ALTA

THE SPANISH CONQUEST of northern Mexico would have been much more difficult but for the work of the missionaries who accompanied every expedition. To these zealots fell the task of converting and educating the Indians wherever the civil and military power of New Spain penetrated. The missions they established served not only to win new members for the Church, but to provide cultural centers in the conquered lands.

Since the state of Sonora was far from Mexico City, it was not until 1630 that missions were established there. But by the end of the century the padres, led by Father Kino, had set up a chain of missions which extended up through Sonora and into what is now Arizona, including Tumacacori with its sister missions.

The country in which Father Kino began the work for which he is remembered today was popularly known as "Pimeria Alta," or the "country of the Upper Pimas," to distinguish these tribes from the Pimas to the south. The Pimas and their neighbors, the Seri, were generally more or less friendly to the Spaniards.

Living in agricultural communities along the rivers, the Pimas raised crops of maize, beans, squash, and cotton, supplementing this diet with wild nuts, seeds, fruits, and game. Perhaps their most important single food was the bean of the mesquite tree. Gathered in July when it ripened, it was crushed into a meal and stored away in large thick cakes.

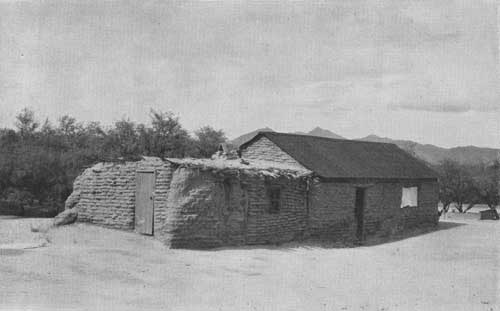

The Pima houses were similar to modern Pima dwellings. Upright posts supported a latticework of light poles and branches and a heavy adobe plaster. Adjoining the houses were ramadas, large roofs supported by four posts and used as sun shelters. It was beneath these structures that most of the family activities, such as cooking, eating, spinning, and sleeping, were carried on.

The Pima village usually consisted of a loose cluster of houses grouped around a large plaza where games and ceremonies were held.

In constant conflict with both Pimas and Spaniards were the bands of Apaches who lived in the mountains north and east of Pimeria Alta. These hardy, nomadic tribes had little respect for the agricultural Pimas who often encouraged the conquerors from the south to establish missions in their midst. Bitterly opposed to the Spanish conquest, the Apaches were a formidable obstacle to Father Kino and his fellow missionaries.

The work in the Sonora mission field was assigned to the Order of Jesuits, who labored among the Indians there for a century and a half. In their long history of patient work, suffering, and even martyrdom at the hands of the Indians, no name stands out like that of Father Kino.

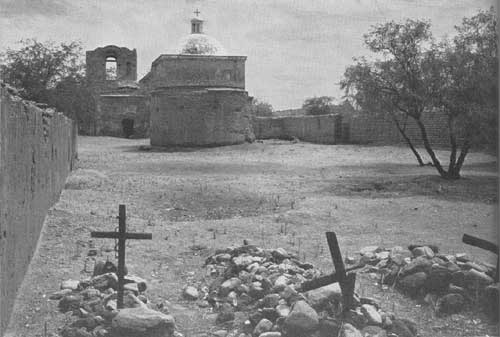

The circular mortuary is in the center of the cemetery, north of the mission proper |

THE LIFE OF FATHER KINO

EUSEBJO FRANCISCO KINO, whose name is so closely linked with the history of the Southwest, was born in 1645 in the Tyrolese Alps, the son of a well-to-do family. At the age of 18 he became desperately ill, and vowed to devote his life to the Church if he should recover.

When his health was restored, he undertook the fulfilment of his promise by preparing to become a Jesuit priest. He began his novitiate in 1665, studying for 12 years at the University of Ingolstadt and other German universities, where he excelled particularly in mathematics.

Obsessed with the idea of serving as a missionary in the Orient, Kino sent one petition after another to his superiors, asking an assignment to China or some other eastern land. When in 1681 he was ordered to go to Mexico, he overcame his bitter disappointment and sailed for America, never to return to the Old World.

Father Kino's first task in New Spain was to accompany Admiral Isidro Atondo on his expedition to Lower California, where the Spaniards hoped to set up presidios and missions. The hostility of the Indians, the difficulty of shipping supplies to Lower California from Sinaloa in western Mexico, and the lack of financial support from Mexico City soon forced them to abandon their plans.

Returning to the capital, Father Kino now had to wait a few years before his next assignment. In 1686 he was given orders to go to Pimeria Alta, where he was to set up a chain of Jesuit missions. For this task he had to raise what was then the huge sum of $30,000, and succeeded. Accompanied by Padre Aguilar, he set forth in 1687 toward the vast country to the north, where he was to spend the remaining 24 years of his life.

For many years the Indians of Pimeria Alta had been aware of the benefits which had accrued to the Christianized Indians to the south. Thus, in the first village at which Father Kino and his party stopped, they were met with demonstrations of friendship. During their day's stay in this village, which was to become the site of the mother mission of Father Kino's chain, they renamed it Nuestra Senora de los Dolores, in English, Our Lady of Sorrows. Continuing the initial survey of his parish, Padre Kino visited four Indian villages, at each of which he made plans to establish a new mission.

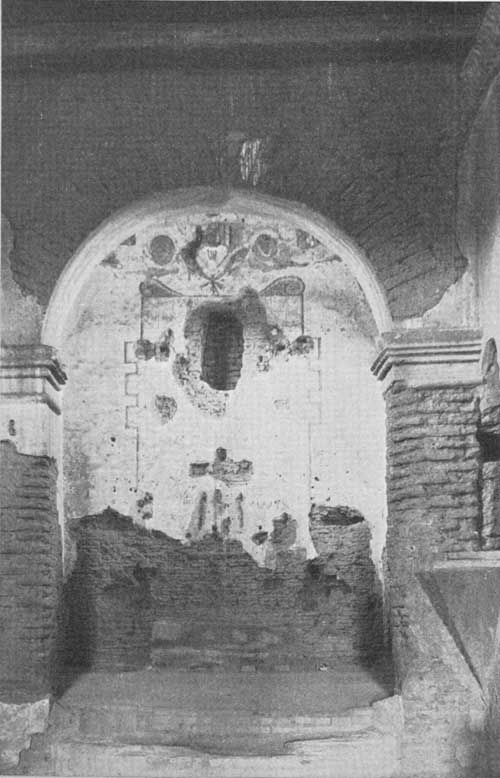

The nave of the mission through the front entrance archway, looking north toward the sanctuary |

Four years later, in 1691, there were already several missions in Pimeria Alta with missionaries in charge. During that year Father Kino accompanied Father Juan Maria de Salvatierra on a circuit of several of these missions.

At Tumacacori stories of the new "Black-Robe" were eagerly repeated by the villagers. They heard how he had come to Pimeria Alta, and they decided to send a delegation to ask him to visit them. In the hills near the present town of Nogales they met Father Kino and, although he had not intended to go farther north, their eagerness made him consent to accompany them to Tumacacori.

Arriving at the village, Father Kino found about 40 houses, plus 3 new brush shelters which had been built especially for his party. One of these was intended as a chapel, another as a kitchen, and the third for sleeping quarters. Father Kino was kept busy by the Indians who brought their children to be baptized and asked repeatedly to have a priest sent to them.

Although it was not until years later that Tumacacori finally became a regular visita (a chapel visited regularly by a missionary), Father Kino included the village on many of his trips.

In 1697 Father Kino came to Tumacacori with a herd of cattle, hoping to give the Indians a higher standard of living. He found a house with "a hall and bedroom" prepared for him by the villagers, who now numbered 147. In addition to well-tilled fields, the village now had sheep and goats which other Christian Indians had brought from a mission destroyed by hostile tribes.

The sanctuary and reconstructed pulpit |

TUMACACORI BECOMES A VISITA

IN 1701, Father Juan de San Martin came to build missions at Guevavi and Tumacacori, about 20 miles apart. The latter was to be a visita of Guevavi, since Guevavi was the larger village. But after a year the priest was ordered to leave, and for 30 years there was no resident priest in southern Arizona.

Although no priest was ever regularly installed by the Jesuits at Tumacacori, another missionary was sent to take charge of Guevavi in 1732. A mission was built there, but the site has never been determined.

The Jesuits were expelled from New Spain in 1767 by order of the King, but when the Franciscans came to Tumacacori in 1768 they found a church and a house for the priest.

By 1793 the hopes of the villagers of Tumacacori had been realized, for the Franciscans had set up a permanent mission there—the principal church in that section of the Santa Cruz Valley.

In the preceding years, Guevavi had been depopulated by Apache raids, so that it was no longer as important as the village of Tumacacori.

Records for 1775 show that the famous explorer-priest, Father Font, accumulated supplies at Tumacacori mission for his journey to San Francisco, which would indicate that it was already an important link in the chain of Southwestern missions.

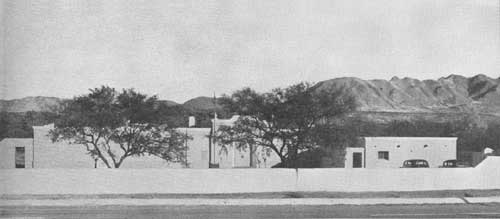

The Tumacacori museum blends with the desert surroundings |

ESTABLISHMENT OF THE PRESENT MISSION

THE NEXT 50 YEARS of Tumacacori's history are relatively obscure, since the only surviving records are routine notations of baptisms, marriages, and burials.

One entry for 1822, however, reveals an important fact. The bodies of two priests who had died at the mission and had been buried there were moved in that year from the old church to a new one. Thus it is reasonably safe to assume that the present building, if not actually finished, was now roofed, so that services could be held in it.

Scarcely had the mission been completed when Mexico won its independence from Spain, and termination of state aid for the missions was followed swiftly by anticlerical laws. By 1827, Tumacacori and her sister churches in southern Arizona were all closed and the last priest had left the country.

The massive bricks and delicate decorations of the Tumacacori mission tell more of the story of its construction than do the written records.

Between 1790 and 1820 the great chain of Franciscan missions was built in Sonora and what is now southern Arizona. Tumacacori mission was probably built during this period.

But from the building itself may be learned other facts. It can be seen that the builder-priest patiently taught unskilled Indians how to lay bricks and make mortar. It is evident he planned his church so that some day he might build a vaulted roof, although at the time of building he had only enough money for a flat one. And then, when he realized he could never achieve this goal, he took the wedge-shaped bricks designed for the dome of the bell tower and used them to finish the walls.

Most of the material for the mission building was prepared at the site. Here the priest supervised the various labors, the molding of the adobe bricks, the kilning of them, and so on.

Seven different shapes of brick were used in the building, including a huge cornice type, a special kind for the tower molding, and a diamond-shaped brick. Only twelve of the latter were used. Still in place, they formed the steps within the dome, to be used in case repairs should be required.

Where walls of great thickness were needed, as in the bell tower, a rubble fill was used with a shell of burned or adobe brick. Walls were well plastered inside and out, the exterior walls being stuccoed. The roof was flat, with huge pine timbers serving as vigas or rafters. These logs were brought from the Santa Rita Mountains, the nearest source of supply.

The church building dominated a series of other structures which included dormitories for the Indian neophytes, storerooms, workrooms, barns, and stables, extending east and south from the mission proper.

When the new Mexican government left the missionaries without financial or military support, Tumacacori was closed, and most of the smaller articles of value were removed, probably to Sonora. Many heavier items, including several statues, had to be abandoned, and the large bells were buried.

TUMACACORI 1827-1921

FOR MANY YEARS the once proud mission stood deserted. In 1849 it was visited by gold seekers on their way to the West, and it is mentioned in many of their diaries. With the Gadsden Purchase in 1853 of territory that was to become part of Arizona and New Mexico, Tumacacori was finally brought into the United States. In its official report to the Government, the boundary commission described the mission as being in ruins.

As the years went by, legends began to spring up about the Tumacacori ruins. Such a fine building in so isolated a region, it was believed, must have great riches buried within it. The fact that there were mines nearby served to give credence to these tales of hidden treasure. Thus the mission became the prey of countless vandals who dug both inside and out in their quest for gold and jewels. Never, it seems, did they consider that a church which had been too poor to complete its bell tower could scarcely have left buried treasure.

When excavations were made in 1934-35, it was discovered that not one room had been left undisturbed by the treasure-hunting vandals.

During the years before the War between the States, Tumacacori and the surrounding region were inhabited by Mexicans and others engaged in mining. In that period there were about 150 silver mines in the vicinity of the old mission.

With the outbreak of the war in 1861 and the abandonment of Arizona by the United States Army, the settlers deserted their ranches in the Santa Cruz Valley and left them to the mercy of the Apaches. When the California Volunteers arrived in 1861-62, however, a certain amount of order was restored.

In the years since the War between the States, native families have occupied the buildings at Tumacacori, while the Papago Indians buried their dead in what they considered the sacred grounds of the mission. Vandalism continued to wreak havoc with the church before the national monument was established. Even the bricks of the mission were stolen by neighboring farmers for use in their own buildings.

Until 1921 the mission stood unrepaired. Eight feet of dust and debris lay in the nave and sanctuary. Bushes grew on the uneven mounds made by fallen roof and adobe brick. The wall of the statue niche above the high altar was knocked out, making it appear to have been a window. Over the facade, the pediment had fallen or been pushed over, while the bell tower stairs had been dug out and the debris thrown into the baptistry. Only the massiveness of the structure saved it from complete destruction.

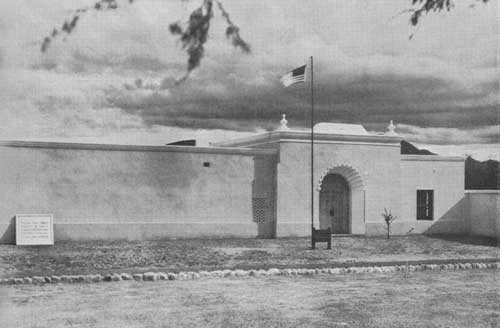

Another view of the museum, showing the fluted arch over the door |

The courtyard of the museum |

West side of the mission, with the peculiar plaster decoration of the cemetery wall |

RECONSTRUCTION AND EXCAVATION

WHEN it was decided to repair the mission in 1921, only work which was absolutely necessary was done. The first important task was to build up the walls where their tops had crumbled and to construct a new roof. Methods approximating those of the original builders were used; the bricks were made on the grounds, and the timbers for the roof were brought from the mountains in the vicinity and hewn by hand. Exact sizes and shapes of the bricks were duplicated, the coping on the bell tower was restored, and the pediment was rebuilt from an old photograph.

The roof showed the usual ocotillo ribs, typical of Southwestern buildings, above their dark-stained vigas. A modern roof was installed over this for greater protection against the weather.

New stairs of bricks worn down to blend with the older ones still in place were installed in the bell tower and the sacristy. One of the side altars was restored by resurfacing its flat top, and new stairs were put into the sanctuary. But no redecorating was done and no new objects were introduced.

In the winter of 1934-35, a complete excavation of all the rooms adjacent to the mission and of the church floor itself was made. At this time the remains of the two priests who had been buried there more than a century before were disinterred and transferred to San Xavier at the request of the Franciscans there.

Although the size of the quadrangles and the rooms surrounding the mission were determined and mapped, very few old artifacts were recovered in this excavation. Most of the artifacts discovered were combs, tin cans, and other evidences of recent depredations. The condition of the rooms indicated that those who had ransacked the building from year to year had discovered old artifacts and made off with them.

Thus the myth of "buried riches" was definitely shattered, but only after years of vandalism had all but wrecked a once fine building.

THE MISSION TODAY

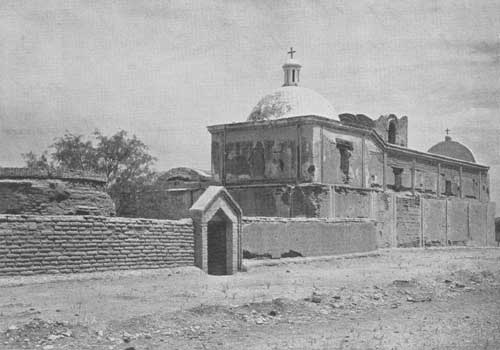

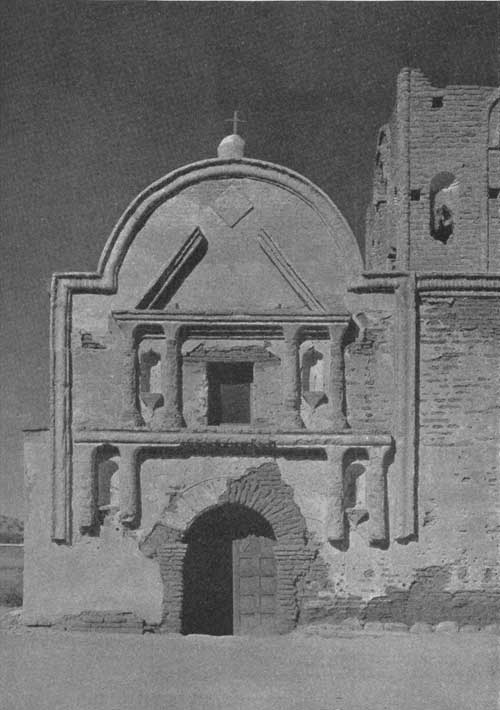

TUMACACORI today is still an impressive building. On its buff-colored facade may be seen traces of the bright-colored plasters—orange, red, black, and blue—with which the pilasters and niches were once covered. Not only by its size, but also by its spectacular coloring the mission building easily dominates the smaller and plainer structures which surround it. Although the exterior has suffered considerably from both weather and vandalism, much of its original beauty is still evident.

Upon entering the mission, the visitor is impressed at once by the length of the high nave. Originally a choir loft across the rear of the church (the end next to the door) cut off some of this length. The height, however, was always noticeable because of the narrow width of 17 feet.

Remains of the high altar and the side altars, which once were surmounted by large statues of various saints, still remain. At one time some of the statues were surrounded by plaster-gabled arches.

The church wall itself was originally white with a red and black dado, or skirting; the most elaborate designs and bright colors were used in the sanctuary.

On the inside of the dome may still be seen faded remnants of the reds, blues, and other colors with which it was painted. Traces of 12 small rectangular moldings show where once pictures (probably of the apostles) were painted or hung. Large canopies painted on the walls on both sides of the main altar indicate the position of statues. The niche over the altar, the central position in the sanctuary, was reserved for another statue. Around the dome runs a turquoise blue border festooned with pomegranate blossoms.

Looking down at the mission from the hills on the west side of the valley. In the background loom the Santa Rita Mountains |

East of the nave is the baptistry, a small room built into the base of the massive bell tower. A restored set of steps goes up to the bell room where four large bells once hung in the arches. The type of bell which was used in Tumacacori was rung with the bell stationary and the clappers in motion. Grooves worn by the bell rope are visible in the west arch.

The bells of Tumacacori have had an interesting history. Some years ago a Mexican who knew where they had been buried dug up the clappers and sold them to the University of Arizona. They have since been presented to the monument. The bells themselves have been the object of widespread search. When one of them was finally found—smashed into many tiny pieces—it was difficult to identify it. Apparently the bells had been removed from their original hiding place before 1921. On the remaining portion of the rim that was found, the words "Santa" and "Anno" can still be traced.

The walls of the bell tower are the thickest in the mission. On the ground floor (i. e., in the baptistry) they are 9 feet thick, and in the choir robing room immediately above they are 7-1/2 feet in thickness. The walls of the bell tower itself measure 5 feet 3 inches. There has been much discussion as to whether it was intended to put an additional story on the bell tower before roofing it; the thick walls are used as evidence supporting this theory.

The sacristy is a large square room east of the sanctuary. Here the priests robed, and here the small staircase ascends to the pulpit.

The pulpit itself was completely destroyed, leaving only plaster marks and the large hole where the entrance had been. In San Ignacio mission, Tumacacori's twin in the Franciscan mission chain, the pulpit is of an octagonal shape and is brightly decorated. The present rough restoration of the Tumacacori pulpit is, however, square.

An old adobe house adjoining the main building. A tower once projected above this structure |

In the nave and sanctuary, names may be seen high on the walls, indicating the great depth of dirt and debris that lay on the mission floor before it was restored.

On the exterior walls of the church the design in the stucco catches the eye. Handfuls of black gravel and crushed brick were slapped on the walls at fairly regular intervals.

The pediment over the facade is surmounted by a cross and ball. Part of this ball is original, the piece having been found by accident during repairs.

Adjoining the mission is the cemetery, in whose center stands a small roofless mortuary chapel which, like the bell tower, was never finished. Long after the abandonment of the mission the cemetery was used by neighboring Indians, and many of the graves are fairly recent. East of the cemetery are the walls of a four-room structure which is the sole remnant of the long rows of dormitories and workrooms that are now only low mounds of adobe.

A corner of the museum |

THE MUSEUM

THE MISSION itself is unfurnished and has been only partly restored to its appearance before 1827; but the museum building nearby, constructed in 1937 with P. W. A. funds, has been fashioned in the style of the Sonora missions. Its walls are of sun-dried adobe, cornices of burned brick, and exterior walls finished with stucco. The carved entrance doors duplicate the carved doors of the mission of San Ignacio de Caborica, while other features of the missions have also been reproduced.

By means of various types of exhibits, the museum brings to life the old days when the mission was a busy center of activity. There are the Pima and Papago Indians who once lived on the desert in freedom. Then the Spanish conquerors of the sixteenth century, followed by Father Kino and his missionary bands, are portrayed. The founding of Tumacacori is shown, with the mission people and their various occupations: mining, gardening, harvesting, manufacturing, trading. The neophyte Indians kneeling in prayer and the grim soldiers who protected this outpost of the Spanish Empire are all there. Next are seen the Franciscans who built a new mission at Tumacacori, and the Indians who burned the mission in 1824. The crumbling walls, the treasure hunters, and finally the coming of the Federal Government complete this picture of many centuries of historical development.

Other outstanding features are a model of the mission as it appeared at the time of its greatest development, and an electric map which shows the routes of the Spanish explorers by means of flashing lights.

Interior of cemetery from northeast corner |

Main building of the church from the southwest |

Facade of the nave |

VICINITY MAP — TUMACACORI NATIONAL MONUMENT, ARIZONA

(click on image for a PDF version)

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> |

1940/tuma/sec1.htm

Last Updated: 20-Jun-2010