|

TREES OF THE FOREST: Their Beauty and Use |

|

Light, Water, Soil, and Space for Growth

What are the National Forests from which much of our timber comes?

Trees are their dominant characteristic, but trees are hardly alone or even self-sufficient, for a forest is a vibrantly complex, interwoven community of many forms of life. Within its depths the tree, shrubby plant, large animal, and minute creature struggle together and against each other to survive and to perpetuate their species.

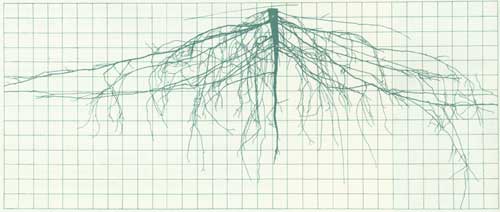

From the beginning to the end of its days, the tree exerts a ceaseless effort in the contest for life. Like man, it must have air, light, heat, water, and food. Having once taken root, it can never move to another spot—yet within its own sphere it acts and reacts in drawing nourishment from soil and air. Roots penetrate downward for water and mineral foods. The trunk carries these to the crown and outward to the leaves. Meanwhile, within tiny leaf cells the amazing green pigmentation called chlorophyll captures light waves and the energy of the sun. These combine with carbon dioxide breathed from the air to form a simple sugar, later converted into other carbohydrates and then into wood. The tree shows its growth and age through the addition each year of a coat of new wood cells formed by the cambium layer between the outside layer of the sapwood and the bark. The sapwood is the living tissue through which water passes from roots to crown.

In field and lawn, the shade tree has space to reach upward and outward for its sunlight. As it grows, the limbs spread and the crown becomes broad and rounded. But the forest tree lives close to its neighbors, and in turning to the sun must reach upward. Its lower branches, cut off from sunlight, wither and fall. It develops height, with a long, clean trunk, attractive to the eye and highly suited for the milling of its wood into thousands of useful products.

|

| F-492429 |

Beneath the canopy of upper limbs and leaves, openings on the forest floor fill with little trees. They shoot up from the ground or sprout from the stumps of old trees which have died or been cut. They test their strength to survive against lesser plants, insects, and animals, for whom they are the sustenance of life. And they must compete with each other.

But survival of the fitter does not produce National Forests of the fullest value in our modern day, for not all tree species are useful to man. These and other undesirable forest vegetation fight for their share of soil and water and, if strong enough, crowd out or slow the growth of more desirable trees. Very old trees, like very old people, become afflicted with infirmities. They suffer disease and decadence; unlike people, they seldom die alone, for they threaten an entire forest by inviting infestation by insects and creating conditions favorable to fire.

Through forest management and its implements, including timber cutting, National Forests are cared for in their own best interests and in the interests of man. The most useful trees are perpetuated in their proper environment through silviculture (silva, the forest, and culture, to cultivate), the science of producing and caring for a forest.

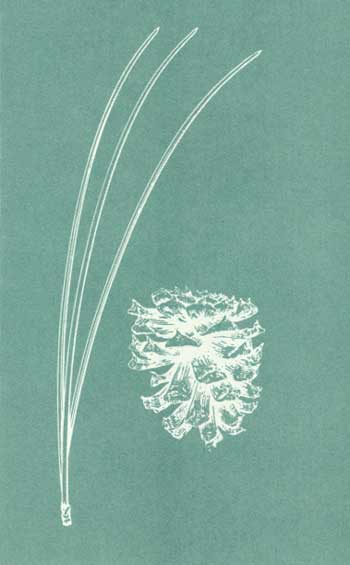

How does this work? The Forest Service ranger, to begin with, must understand the surroundings in which specific trees are born from their seeds and the conditions which produce their best growth. He must also be familiar with society's use and needs for timber-type trees. These constitute two general classes: Softwoods or conifers, the mostly evergreen cone bearers; and the hardwoods or broadleaf trees, of which most are deciduous, that is, shed their foliage in the fall.

Among the conifers are pine, fir, spruce, redwood, and hemlock. Conifers, the oldest of tree families, were widespread on the face of the earth millions of years ago. The somber giant sequoias still stand as living history pre-dating the birth of Jesus. Bristlecone pines have been found that range from 4,000 to 4,600 years old. Conifers are the main strength of America's timber resources, providing four-fifths of the large sawtimber trees. The conifer is called softwood and is used extensively in construction and fiber for paper pulp.

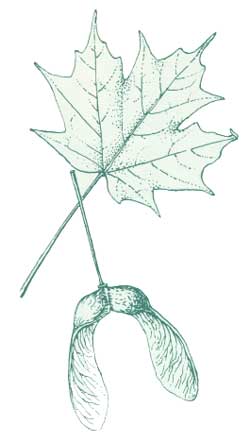

Broadleaf trees include oaks, maples, elms, and sycamore. Their wood is used in furniture, among other purposes, and together they are called hardwoods (although a few are softer than some softwoods).

The forest manager knows that deciduous trees require some moisture throughout the year, while conifers can survive where it is concentrated mostly in winter snowfall. But this is only the start, for there is also the magic of tree seeds to fathom, interpret, and adapt.

Seeds range in weight from the heavy, large black walnut down to specks almost as fine as sand. Some are borne on wings, so remarkably balanced that they ride the winds for miles. Some are sown only by birds and other animals—if not consumed by them first! Many trees produce seeds every year, others less often or irregularly. Of every 100 seeds reaching the ground, only a few may sprout. And the cones of some trees, like jack pine in the Lake States (sometimes called fire pine), and knobcone pine in the West, are opened and their seeds prepared for germination by fire.

The forest manager must reckon with seed behavior and the complex conditions required for seeds to take root and reproduce the forest. Some are best allowed to seed naturally from mature parent trees. Others are best sown by hand or by airplane. Millions of seedlings are grown in National Forest nurseries and are planted in the forest by hand and by machines. Then, once in the ground, the young trees (plantations) may require some shade to survive, freedom from competing brush, and protection from animals, insects, and fire. Providing this is called plantation care.

Forest trees are also classified by their tolerance and intolerance to shade. Sugar maple, for instance, is called a tolerant tree because it will endure as a youngster with only a minimum of sunlight under the cover of taller trees. But Douglas-fir is relatively intolerant to shade, as is black cherry.

Various silvicultural cutting practices are used to obtain the desired degree of light and to encourage seedling establishment. Cutting can alter the density of the forest canopy or overstory to enable more light to reach the forest floor. Or it can open a new bed for seed if located the proper distance from nearby uncut stands. For southern pines, such a distance is usually not over 500 feet; for red spruce, in contrast, it may be as far as 1,500 feet.

In essence, three systems of harvest cutting are applied on the National Forests: Selection cutting, seed tree cutting, and clear cutting, with variations based on specific terrain and other conditions.

Some forests are best managed through selection or partial cutting. In starting harvest of a virgin stand, older trees are cut first. So are the defective and diseased. Younger, healthier trees are encouraged, by this release from competition, to further growth—much like the weeding of a garden. The forest is also opened to stimulate new seedling growth. In seed tree cutting, the entire stand is logged except for a few carefully selected seed trees which are left to regenerate the forest. These, in turn, are harvested after the new stand has been successfully started.

Douglas-fir, however, is one of several species best managed with clear cutting in blocks. Selection cutting of the lusty giant has been tried in the National Forests, but with little success. It proved difficult to remove the tall Douglas-firs, standing over 200 feet, without seriously injuring others as they fell. Those remaining in a stand, shorn of protection from neighboring trees above and interweaving roots below, became victims of blowdown in high winds. Nor would Douglas-fir reproduce itself without benefit of full sunlight. Thus, clear cutting or patch cutting is practiced on blocks of 40 to 100 acres; this enables sunlight to reach the ground and to help the valuable Douglas-fir forest renew itself. Seeding by hand or by airplane and planting nursery-grown seedlings are methods used to reforest these large openings.

|

| F-483785 |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

PA-613/sec2.htm Last Updated: 12-Sep-2011 |