|

A History of the Daniel Boone National Forest 1770 - 1970 |

|

CHAPTER I

EARLY EXPLORATION

The Daniel Boone National Forest in Eastern Kentucky lies in one of the most historic regions in America. The history of its exploration and early settlement is one of the most interesting and exciting phases of American history.

By early in the 16th-Century the tales of Indians regarding this area, its great forests, huge game herds, magnificent rivers and rich land, had excited the imagination of the French and English alike. Both nations laid claim to this vast heartland of America.

History tells us that the French, from their developed colony in what is today Canada, were among the first white men to set foot in the area. In 1669, Robert Cavelier de La Salle, the French explorer, transversed the Ohio River from the Big Sandy to the Falls of the Ohio. In 1671, Thomas Batts, with a party of Virginians in search of the great western river described by the Indians, crossed into the valley of the Ohio. In 1673, J. Marquette and Louis. Jolliett passed the mouth of the Ohio on their trip down the Mississippi River. In 1739, another French explorer, Baron Longueil, explored a portion of the Ohio River. In 1742, an English explorer, John Peter Sallings, traveled in the area; and in the same year, John Howard, another Englishman, made a trip down the Ohio River.

By 1749, the French were making formal claims to lands along the Ohio, sending Celeron de Blainville from Montreal to explore and claim the area in the name of the King of France, Louis XVI.

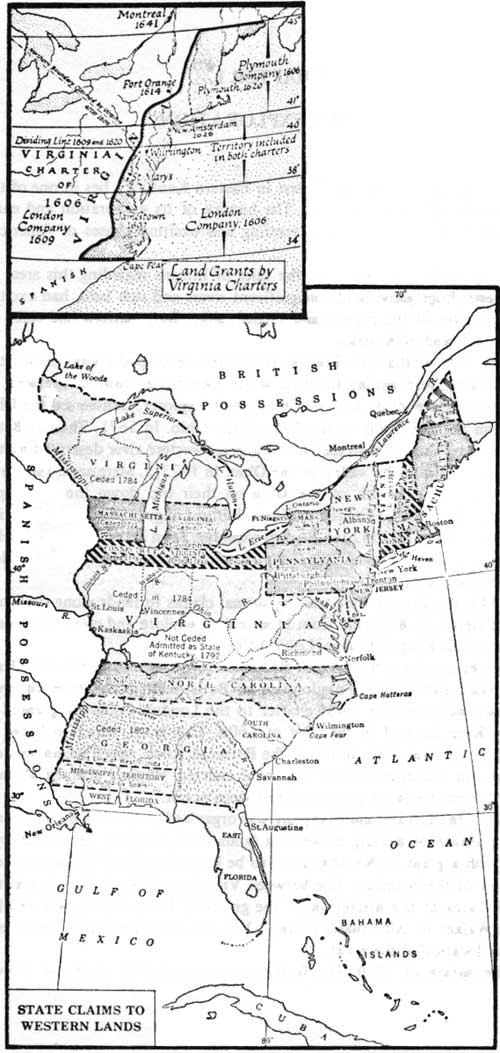

Not to be outdone, the English also made formal claims to the area. Their claims, based partly on the exploration of Batts, Sallings and Howard, were also firmly based on the royal charter to the London Company granted to them by King James I in the year of 1606. This grant, which included all territory from Cape Fear north to the Potomac River, specified no western boundary. In accordance with this royal charter, Virginia claimed all land westward from the above point to the western ocean.

In 1748, the Loyal Land Company was organized in London by Virginians for the purpose of dealing in western lands. The company secured a royal charter with a grant of 800,000 acres to be located north of the due western extinction of the boundary line between Virginia and North Carolina in the Kentucky area at the discretion of the grantees. The company selected Dr. Thomas Walker of Albermarle County, Virginia, to inspect the country and select the location of the grant.

In the spring of 1750, Dr. Walker, accompanied by Ambrose Powell, William Tomlinson, Colby Chew, Henry Lawless and John Hughes set out on this mission. Crossing the Blue Ridge and seeking information from settlers and hunters along the way, the party arrived at a pass through the mountains, known as Cave Gap, on April 13, 1750. This sharp break in the high mountain walls of the western rim of the Appalachians was the most important discovery of the expedition. Through this gap, later known as Cumberland Gap, would pass hundreds of thousands of people enroute to settle the limitless western country beyond.

|

| Colonial Claims to Western Lands (click on image for a PDF version) |

Continuing through the gap and following a well-traveled Indian road, known to the Indians as Athawominee (The Path of the Armed Ones or the Warrior's Path), the party continued down Yellow Creek and Clear Creek until they encountered a large clear river sweeping out of the hills from the northeast. This river, known to Indians and hunters as Shawnee River after the last permanent residents of the area, Dr. Walker named the Cumberland River in honor of the Duke of Cumberland, who was then a national hero due to his leading the English army to victory in the Battle of Culloden four years previously.

Finding the river at flood stage, they continued along the west bank following the Indian road to a narrow pass where the river cut through Pine Mountain, later known as Wasioto Gap, to a point just below the narrows where the Indian road crossed the stream. The high water prevented a crossing and they continued along the west bank for several miles through rough hills until they arrived at a big lick at a bend of a creek which, by the many buffalo trails leading to it, appeared to be used by huge herds of these animals. Finding the river still too high to cross by fording, they built a bark canoe and, on April 22, 1750, they crossed the rived in the canoe, forcing their horses to swim.

Safely across the river, the party arrived at a large bottom of fertile land where Dr. Walker decided to build a cabin in evidence of their claim to the territory. Drawing lots to determine who would build the cabin, salt down the meat of a bear they had killed and plant corn and peach stones, Dr. Walker and two companions then continued westward from the cabin site, located about eight miles below the present town of Barbourville, in Knox County, Kentucky. Continuing westward about 20 miles and finding the land poor, the laurel tangled and the grazing for animals poor, Dr. Walker climbed a tree on a ridge top to look over the general area. Finding the country unsatisfactory for his purpose in all directions, the three returned to the cabin site where their companions had completed construction of a cabin 8 by 12 feet in size, the first cabin built by white men in the area that was to be Kentucky. (A replica of this cabin has been erected on this location designated by the Commonwealth as the Dr. Thomas Walker State Shrine.)

Marking several trees in the vicinity as evidence of their land claim, the party headed north on May 1, 1750. Crossing the Laurel River the explorers again came upon a much used Indian road they correctly identified as the Warrior's Path, which they had left where it crossed the river. Continuing north along the Laurel River for two days, they crossed many streams and found the country rough and undesirable for their purpose. On May 11, the party camped under a large overhanging rock, large enough to shelter two hundred men. From this point, believed to have been on one fork of the Rockcastle River, the party turned eastward for the return trip to Virginia.

It appears that Dr. Walker selected one of the most difficult routes possible for the return trip. They traveled over 200 miles of difficult mountain country, crossing the present Kentucky River (which he called the Levisa in honor of the wife of the Duke of Cumberland) near the present town of Irvine, Kentucky. Camping one night on a bend of the Licking River near the present town of Salyersville, the party crossed the headwaters of the Licking, the Big Sandy and the Kentucky River and, crossing into Virginia through Pound Gap, they reached New River near its junction with the Greenbrier at a place since known as Walker's Meadow.

Dr. Walker has left no comment on his disappointment, and that of his sponsors of the Loyal Land Company, in failing to find desirable country in which to locate the company grant of 800,000 acres. Unfortunately he had failed to discover the beautiful rolling Bluegrass land only a few miles to the north and west of his return route.

As an indication of the abundance of game in Kentucky at that time it is of interest to note that Dr. Walker reported that during the trip his party had killed a total of 13 buffalo, eight elk, 53 bear, 20 deer, four wild geese, 150 wild turkey and abundant numbers of small game. He stated, "We might have killed three times as much game, had we wanted it."

This expedition of Dr. Walker's was the first extensive exploration of the Kentucky country by the English with the objective of locating specific land for settlement. The French and Indian War, even then in the making, was to delay the settlement of this country beyond the mountains for a period of 20 years.

It is interesting to note that a part of Dr. Walker's route crossed country that today lies with the Daniel Boone National Forest.

In 1748 another group of Virginia gentlemen, which included George Washington's half brothers, Lawrence and Augustine, organized the Ohio Company for the purpose of dealing in western land. This company received a grant for 200,000 acres in what is now West Virginia, between the Monongahela and the Kanawha rivers. Later the company was awarded a second grant of 500,000 acres on either side of the Ohio River, below the mouth of the Kanawha, at their discretion. In return the company agreed to erect a fort at the junction of the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers and another at the mouth of the Kanawha River and, in addition, to settle 300 families on these lands.

To locate desirable land for this venture the Ohio Company employed the famous frontiersman Christopher Gist, who lived on the Yadkin River in North Carolina, to explore the Ohio country for them. He was instructed to locate good level land and to make a rough survey of it. He was directed to extend the explorations as far downstream as the Falls of the Ohio, where the city of Louisville is now located, if necessary.

In the spring of 1751, Christopher Gist came down the Ohio, and, landing on the Kentucky shore near Big Bone Lick, proposed to explore downstream as far as the Falls of the Ohio. Becoming alarmed by the action of a body of Indians in that vicinity, he turned southward and, reaching the Salt River drainage, turned eastward, crossing the Kentucky, the Red and the Licking rivers. Beyond these he passed through Pound Gap into Virginia enroute to his home in North Carolina. On his return trip he crossed the route taken by the Dr. Walker Party in 1750. It is interesting to note that the information he gained on this exploration trip, when told around the campfires of General Edward Braddock's Army some four years later during the French and Indian War, would be instrumental in influencing young Daniel Boone to resolve that someday he would live in this fabulous land of Kentucky.

In the fall of 1752, a white trader named John Findley (or Finley), with a stock of trade goods and four white servants, came down the Ohio in canoes as far as the Falls of the Ohio, the present site of the city of Louisville, Kentucky. He had hoped to locate parties of Indians with whom he could contract to provide trade goods in return for their winter catch of furs. Finding no Indians there, he turned back upriver as far as Big Bone Lick where he met a party of Shawnee returning from a hunt in Illinois. They invited him to return with them to their village, promising him good trade there.

Traveling by canoe up the Kentucky River with Indian guides, Findley unloaded his trade goods on the bank of Upper Howards Creek at the Shawnee village of Es-kip-pa-kith-i-ki located about 10 miles from the present site of Winchester, Kentucky. Here he built a log cabin surrounded by a stockade, unpacked his trade goods and was ready for the fall and winter fur trade.

The story has persisted in Kentucky history that this unpacking of trade goods was a most significant event in the development of Kentucky. According to the story, attributed to Daniel Boone and passed down in the Boone family for generations, these trade goods had been packed at Lancaster, Pennsylvania, in a hay known as "English Grass," and which we know today as Bluegrass. Seed of this hay had been brought to the Lancaster area from the homeland by the early settlers. As Findley and his helpers unpacked the merchandise the packing hay was thrown aside. Seed from this hay took root in the rich limestone soil of Es-kip-pa-kith-i-ki and, during the following 25 years, spread across the cleared fields of the Indian village. When white men again came to the village site some 25 years later, the only Bluegrass they found in Kentucky was at Grassy Lick in Montgomery County and at Es-kip-pa-kith-i-ki or Indian Old Fields as the site is known today.

John Findley's dream of a profitable trading venture with the Shawnee was short lived. On January 28, 1753, a large party of Indians consisting of 70 Christian Conewagos and Ottawas, one French Canadian and a renegade Dutchman, named Phillips, came down the Warrior's Path from the vicinity of the St. Lawrence River on a scalp-hunting expedition against the southern Indian tribes. While on the Warrior's Path near the head of Station Camp Creek (Estill County) they met a party of seven Pennsylvania traders and their Cherokee servant. The northern Indians attempted to take the Cherokee's scalp and the traders objected. In the brief fight one of the Indians was shot in the arm. The Indians then proceeded to make prisoners of the white trading party and started on their return to Canada.

While passing through Es-kip-pa-kith-i-ki, John Findley apparently attempted to help his fellow traders. The fight which ensued resulted in the killing of three of Findley's servants and the stealing of all of his property and trade goods. Findley and his remaining servant, John Faulkner, barely escaped with their lives and were forced to make their way back through the winter forest to Pennsylvania.

One of the traders, James Lowry, and his Cherokee servant managed to escape from the Indian war party three days later. The remaining six traders were taken to Canada, and later two of them were sent to France, before they were rescued and returned home.

In reporting this affair to the government of Pennsylvania Major William Trent, Virginia Indian Agent, identified the location as "Kentucky," this being the first time that word appears in the records of the English colony.

In 1754, James McBride is reported to have traveled to the mouth of the Kentucky River.

In 1761, a party of 19 Virginians passed through Cumberland Gap into Kentucky, giving the name of their home county, Cumberland, to the mountains. They apparently had traveled only a short distance into Kentucky before returning back to Virginia.

In the fall of 1763, this same group of Virginians again came through Cumberland Gap, spending the fall and early winter hunting and trapping along the Cumberland River before returning home.

Apparently these hunters found conditions favorable in Kentucky as they again came through Cumberland Gap in 1764. Making their hunt on the Rockcastle River, they came upon a large orchard of sweetly blooming crab apple trees at a great spring. This spot they named Crab Orchard which later became a significant point on the Wilderness Road.

This hunting ground proved to be so fruitful that they returned there each fall for several years. Because of the long trip to these hunting grounds, as well as the long time they were absent from home each year, they were referred to as the "Long Hunters" and so history has recorded them.

On one of these trips their hunt along the Rockcastle River found game scarce. The small group, led by James Knox of Augusta County, Virginia, met a small party of Indians led by a Cherokee chief named Captain Dick, whom they had met previously. Reporting the scarcity of game, Captain Dick invited the party to hunt on "his river" where he told them, game was plentiful. After giving directions for reaching the area the chief cautioned them, with significant emphasis, "To kill only what they needed and go home." Following the chiefs directions, Knox and his party traveled west to the head of the stream described where abundant game was found. In honor of his Indian friend Knox named the stream, "Dick's River," and so it is named to this day. However, sometime in the intervening years, a mapmaker has changed the spelling of his name to, "Dix River," either in the interest of brevity or because he misunderstood the spelling from the spoken word.

On this trip to Dick's River, James Knox explored country through which, many years later, he would help to build the "Wilderness Road."

It is reported that prior to his trip of exploration to Kentucky in 1769, Daniel Boone, then living on the Yadkin River in North Carolina, contacted these long hunters for information regarding Kentucky, and stating as his reason for desiring the information that he had been employed to explore this general area beyond Cumberland Gap for the land firm of Henderson & Company.

In 1767, Isaac Lindsey and four companions from South Carolina came through Cumberland Gap and traveled along a stream having distinctive rock formations along its shore. Because of the resemblence of these imposing rock structures to the medieval castles of Europe, Lindsey named the stream the "Rockcastle River," a name it still bears today.

Following the Rockcastle River south to the Cumberland River, then down the Cumberland to the mouth of Stone's River in what is today Tennessee, this group met Michael Stoner and James Harrod, both of whom were later to become pioneer leaders in the settlement of Kentucky.

These first hunters apparently came to Kentucky in search of fur and skins as well as for the adventure of exploring a new country. However, all of the early visitors to Kentucky were not so motivated. As with every new country, there were questions as to the presence of gold and silver. Some of these early travelers were definitely motivated by the possibility of great wealth from such sources. Among such men were John Swift and his party, whose story has been told around the campfires of hunters of the area and before the fireplaces of the cabins of Eastern Kentucky for the past 200 years. There are many versions of this tale, each having some scrap of documentary evidence or historical facts sufficient to authenticate it in the minds of eager listeners. Historical research indicated that John Swift was an Indian trader, working with the northern Indian tribes well before the French and Indian War. It is rumored that he married a beautiful Indian maiden (the daughter of a chief, no doubt), and that possibly he was made a member of the tribe. He is believed to have traveled with these Indians into Kentucky, where they came to obtain silver, which they traded to the French for various types of trade goods. It is believed that in this way John Swift learned of the presence of silver in the Eastern Kentucky area.

Fortunately, for the documentation of this story at least, trader John Swift was a methodical man who kept a detailed journal of his later travels, which not only provides much of the following information, but also includes a map of the Middle Kentucky River country. It is known that he made a series of trips from his home in Alexandria, Virginia, to the Eastern Kentucky country in 1761, 1762, 1764, 1767-68 and 1768-69. All but one of the earlier trips were made to Kentucky well before Daniel Boone's first visit there. In addition, trader John Swift's diary refers to three other trips, which were not documented, prior to the initial documented trip of 1761. On these journeys, John Swift and his party started from Alexandria, Virginia, proceeded as a group to the head of the Big Sandy River, and from there scattered over considerable area in their explorations, prospecting and mining. These widely scattered operations have served to confuse historians and others not familiar with the entire story.

While there are as many versions of the John Swift silver mine story as there are storytellers, the main stories and legends may be grouped into two principal versions.

The first story relates that John Swift and three companions, Mundy, Gries and Jeffrey, mined silver somewhere in the Kentucky River country, probably in a drainage of the Red River, over a period of approximately eight years (1761-1769). This story says that during that period they smelted approximately $273,000 in silver bullion and coins, which was kept buried in the floor of a Kentucky cave. About 1769, they attempted to bring $70,000 in value back to Virginia. Enroute, they were attacked by Indians, buried the $70,000 worth of silver, and in trying to escape Swift's three companions were killed. Swift eventually reached the eastern settlement and his home in Alexandria, Virginia. This means that the $70,000 worth of silver was buried somewhere on a trail between the Red River and the eastern seaboard settlements where, as far as is known, it remains today providing the irresistible lure of the secret of buried treasure, as it has in each of the succeeding generations since that day. The remaining $200,000 of silver bars was left buried in a Kentucky cave and, as far as it is known, remains there to this day.

The second version of this story is similar, but takes a more sinister turn. This story states that when John Swift returned to the Kentucky country of his earlier adventures with the Indians, he was accompanied by a motley crew of adventurers, including ex-sailors, ex-soldiers, and a few well-known pirates and cutthroats from the seaboard settlements and the Spanish Main. It is recorded that one of the members of his party was a former worker in the mint of England. The party came into the region with several loaded pack-horses; and, when they started back to Virginia a few months later, the packhorses were more heavily loaded than when they came in.

On one thing all stories are in agreement. John Swift and his companions were refining silver ore and were making counterfiet money. This is verified somewhat by a later story that John Swift was put on trial in Alexandria, Virginia, for counterfeiting, but was acquitted at this trial and released when it was proven that his pieces-of-eight contained more pure silver than did the coinage of either Spain or England.

Here again, the trail branches out in speculation over where the silver came from originally. Some believe, as in the first account, that Swift and his companions mined and smelted this silver on location, although geologists have stubbornly maintained that there is no silver ore in Kentucky. Another story, which has some basis of fact, is that the silver bars were taken from Spanish ships, either captured by the English navy or by pirates working in connection with Swift and his companions. It is well established that Swift had connections with the piracy trade of his day and time, and was part owner in 12 ships sometimes engaged in that trade. Further rumor has it that he was forced to testify at the trial in England of his fellow buccaneer, Black Beard. If this could be established as a fact, it would lend much credence to the entire Swift Silver Mine story. From this point, the main version of the second story closely parallels that of the first; that is, while packing the silver back to the Virginia settlement, the party was attacked by Indians, Swift's companions killed, and the treasure buried along the trail. At this point, another sinister version of the story relates that the party was not attacked by Indians on the return trip, but that John Swift, wishing to have the entire treasure and location of the mine for himself, killed his companions, buried them and the silver on the trail, and returned to the settlement with a story of Indian attack to explain the absence or non-return of his companions.

It is related that shortly after his return to the seaboard settlements, John Swift traveled to England in the hope of interesting investors there to the extent of outfitting an expedition to recover the caches of rich silver bullion and to operate the fabulous silver mine further. While in England, the American Revolutionary War broke out, and, because John Swift had made many public statements as a true American and had given the public his opinion of the king and others, he was jailed in Dartmoor Prison where he remained until the end of the American War of Independence. As a result of spending many years in a dark and damp cellblock, John Swift lost his eyesight and returned to the colonies a blind man.

Once back in the colonies, "Blind John," as he was known, was unable to go into the woods by himself. As a result of his fabulous tales of lost treasure, he was able to interest and assemble a party who agreed to accompany him to Kentucky in an attempt to recover the treasure. On this exploring trip his principal companion was a man by the name of Anderson, who wrote, "It was pitiful to see the old man hobble over the rocky ground, up cliffs and across the mountain streams, searching frantically for the site of his former mining adventure." For 14 years, Blind John Swift, accompanied by various companions, attracted by his stories of fabulous wealth, searched the Kentucky country for the identifying reference marks he recorded in his journal that he had made to assist in relocating the various caches of buried treasure. In the year of 1800, broken in spirit and in body, John Swift lay dying; and, with almost his last breath, he admonished his companions: "It is near a 'peculiar rock', boys. Don't never quit hunting for it. It is the richest thing I ever saw. It will make Kentucky rich."

Since that day, hardly a year has passed that one or more searching parties had not been found in the hills of Eastern Kentucky, usually with a copy of the journal and a map, which someone has sold them as, the original, searching diligently for the lost treasure. As an example of the type of marking in Swift's journal which excites the interest and inflames the passion for finding buried treasure, is this entry: "On the first of September, 1769, we left between $22,000 and $30,000 in crowns on a large creek, running near a south course. Close to the spot, we marked our names (Swift, Jefferson, Mundy, and others) on a beech tree . . . with a compass, square and trowel (Masonic symbols). No great distance from this place, we left $15,000 of the same kind, marking three or four trees with marks. Not far from these, we left the prize, near a forked white oak, about three feet underground and laid two long stones across it, marking several stones close about it. At the Forks of Sandy, close by the forks, is a small rock, has a spring in one end of it. Between it and a small branch, we hid a prize under the ground; it was valued at $6,000. We, likewise, left $3,000 buried in the rocks of the rock house."

For nearly 200 years the lure of John Swift's lost mine and buried treasure has served as a Kentucky El Dorado. John Swift's dying words have rung in the ears of prospectors and treasure seekers as a certain promise of riches. The "boys" have never given up the search. One of these was old man Cud Hanks at Campton, Kentucky, who tramped the hills above the town looking for Swift's silver lode. Uncle Cud claimed that he knew Sailor John, and that he had first-hand information of the mine. Like the others, death overtook him, too, before he could find the precious cache. While many communities in Eastern Kentucky believe that their community is the real site of John Swift's fabulous silver mine, the majority of treasure seekers tend to concentrate their search on that portion of the Daniel Boone National Forest along Swift Camp Creek between the vicinity of Rock Bridge and the junction of the creek with the Red River. This area of high cliffs, rough and broken topography, and lack of clearly marked trails, may well provide succeeding generations of treasure seekers with much-needed, strenuous, physical exercise and many hours of enthusiastic and romantic contemplation. If the past is any indication, the future will not want for searchers for the Swift Mine Treasure in the Daniel Boone National Forest.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

region/8/daniel-boone/hsitory/chap1.htm Last Updated: 07-Apr-2010 |