|

Looking at Prehistory: Indiana's Hoosier National Forest Region, 12,000 B.C. to 1650 |

|

Looking at Prehistory:

Middle Archaic Period 6,000 to 4,000 B.C.

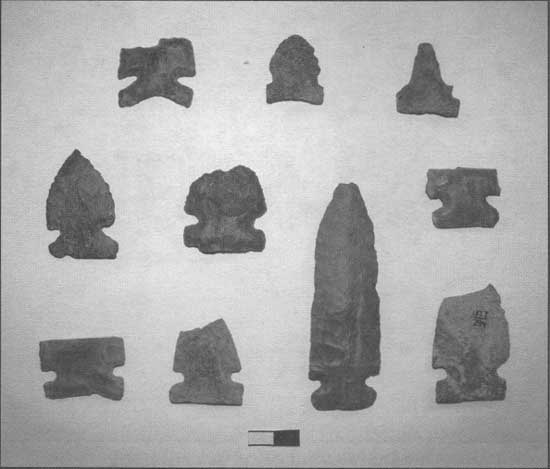

Hunters and gatherers living during this period experienced the time of maximum climatic warming following the Ice Age that extended into the middle of the Late Archaic period. After that, yearly temperatures began cooling, once more becoming like the climate of more recent times. Projectile points such as Godar and Raddatz, belonging to the Large Side Notched cluster, are the main types that mark this period in Indiana (Figure 41). Other types of projectile points are common during this period in the Middle South, the Southeast, and elsewhere but few examples of these southern tool traditions were carried in hunting expeditions as far north as the Ohio River. Except in rare cases, most of the archaeological sites across the Midwest, including Indiana, seldom produce Middle Archaic tools and other remains in large quantities until the latter part of the period when there is less movement of groups of people and longer and more substantial use of base camps.

|

| Figure 41: Large Side Notched projectile points from Rockhouse Hollow and other sites recorded in hill country. Some of these are broken from use while others show heat fracturing from being discarded in campfires. The upper row includes a hafted scraper made from a projectile point (left), a point with a nearly exhausted blade from resharpening, and a drill form made from a projectile point. |

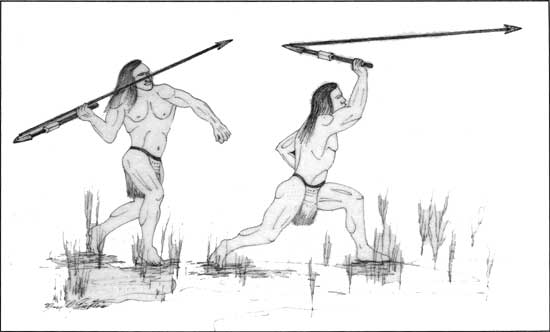

While the atlatl or spear thrower was probably in use from the earliest human occupation of the Americas and even earlier in Europe (Figure 42), polished stone atlatl weights appear for the first time during the Middle Archaic period. During the next 4,000 years, a wide range of styles of atlatl weights are developed in the Ohio Valley that probably mark significant cultural differences between groups of people (Figure 43). These polished stones are ingenious creations and highly decorative in design and finish. These required both time and skill using hard sand grains and hollow tubes to drill straight holes through the centers for mounting on wooden shafts. The tubes were probably made from sections of cane with the sand glued to the ends, in effect making sets of tubular drills. Such precision drilling probably employed the bow and drill to apply torque and consistent motion. Various rock types were selected for atlatl weights. Some of the more common ones include red and green slate, quartz, granite and schist.

|

|

Figure 42: The atlatl in action. Throwing an

atlatl requires a secure grip on the spear thrower (atlatl) and spear to

keep the two engaged until the spear is cast. On the average, the use of

the spear thrower or atlatl improves the ability to cast a spear farther

and faster due to the mechanical advantage of lengthening the arm and

thereby increasing the amount of thrust and killing power of the

weapon. Feathers were probably added to the spear to increase accuracy. In effect, the ancient spear was essentially a large arrow that only needed to be made smaller when the bow was developed thousands of years later. The atlatl was a shaft of wood with a carved hook often of deer antler to engage a hollowed area in the end of the spear. The handle was also often made from deer antler. A stone weight added to the shaft of the atlatl served as a counterbalance during long hunts when the spear was engaged and was also a way of adding additional thrust. There are many types of atlatl weights during the Archaic period that probably represent different groups of people. |

|

| Figure 43: Semi-lunar and "knobbed" atlatl weights made from banded slate and porphyry. These appear in the archaeological record beginning about 6000 B.C. Over the next several thousand years, many different types of atlatl weights or "bannerstones" are developed. |

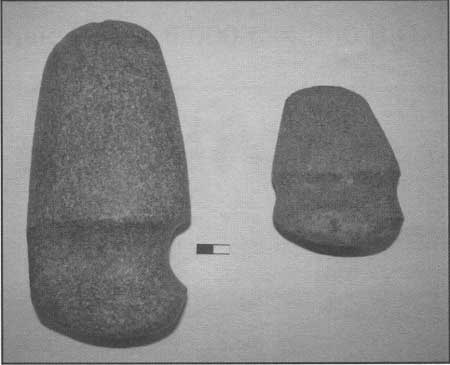

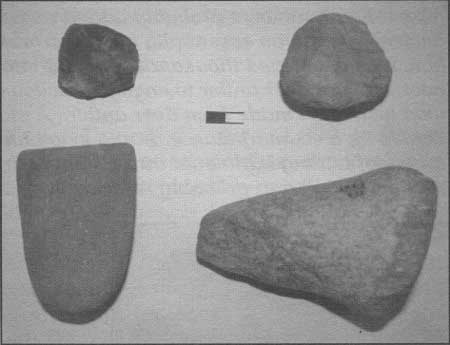

Ground stone tools, often made from granitic cobbles left behind by the glaciers, are common occurrences at this time and are used by all prehistoric peoples after the Middle Archaic period. Grooved axes made by pecking and grinding, rather than flaking, became important tools for girdling trees, splitting logs, breaking firewood, dug-out canoe making, general wood working, and other uses (Figure 44). The appearance of the grooved ax marks a time when people began cutting back the forests to perhaps give nut producing trees more light. This would have also increased the productivity of other wild plant foods. In addition, obtaining firewood would require labor intensive forays at increasing distances from major camps, once the natural deadfall and driftwood was consumed, if ways of killing and felling trees had not been developed. Mortars and pestles, pitted stones and grinding slabs appear in large numbers showing an increase in the use of nuts (especially hickory) and other plant foods (Figure 45). We know that the drier climatic conditions favored the expansion of oak and hickory forests at this time. Deer hunting, along with nut and seed collecting on a seasonal basis were still the food mainstays along with a host of smaller game and plants. Perhaps mortars pecked into bedrock and large sandstone blocks became popular during this time (Figures 46-47).

|

| Figure 44: Two types of grooved axes made from granite. The axe on the right is fully grooved around the circumference for tying on to a handle. Full grooved axes appear around 5000 B.C. in the archaeological record. The specimen on the left is only 3/4 grooved leaving a flat spot where a wedge of wood or bone could be inserted to tighten the haft after heavy use of the ax. The latter type is an improvement on the full-grooved ax after it had been in common use for about 2500 years. |

|

| Figure 45: Bell pestles of granite and limestone (below) for use in grinding and pulverizing seeds, nuts and other food. The round rocks (above) are chert hammers that were heavily used to batter (peck) and shape granite cobbles to make axes, pestles, and other tools. These probably started out as discarded angular cores from flaking chert to make blades, bifaces, and projectile points. Nearly all of the sharp angles have been removed from repeated battering. The small light and dark spots on one of the pestles is the result of pecking with a chert hammer. |

|

| Figure 46: A prehistoric mortar for grinding nuts, seeds, and other foods battered into a large moss-covered sandstone block that fell from the roof of Celina Rockshelter. |

|

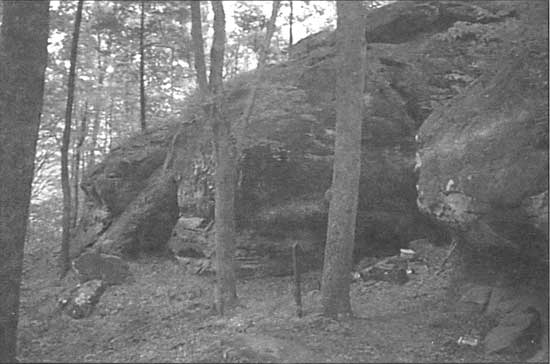

| Figure 47: A view of Celina Rockshelter. Excavations by archaeologists from Ball State University revealed the shelter was used for short-term camping beginning in the Early Archaic period and use continued into the Woodland period. Excavations were terminated when breakdown of massive sandstone was encountered at nearly two meters below the surface. |

Local chert raw materials of all kinds found near camps within hunting territories were regularly selected for manufacturing projectile points. There was little or no reliance on major chert quarries to supply raw material for flint knapping needs. For example, at Rockhouse Hollow Shelter the Middle Archaic projectile points are nearly all made from different raw materials obtained locally, with few coming from locations beyond the hill country. Resharpening and reworking the tips of the projectile points is common during this period, indicating the points were regularly recycled as hide scrapers. Atlatl weights, flake debris and many other items were discarded in the rockshelters at this time.

People living in the Midwest during the Middle Archaic period may have been concentrated into smaller areas or, more importantly, may have used the landscape differently than previous people had done for hunting and collecting. At least the evidence indicates there are fewer campsites and fewer tools to mark where they camped compared to those pertaining to the Early Archaic period. Most evidence suggests the environment was not too warm and dry for plants, animals and man to survive. Pollen evidence, on the other hand, suggests the environmental conditions favored plants that flourish in dryer conditions and prairie areas may have experienced less productivity. This may have led people to use more biologically rich areas, such as the Ohio River valley, for major camps without a need to establish many smaller camps any great distance away from the river. There are few signs that camps located in other areas, including smaller tributary streams, were used to any great extent. This conclusion is based upon excavations at sites in the valleys now impounded by Lakes Monroe and Patoka.

The big rivers were apparently shallow enough in the summer months to attract people there to collect mussels and fish, which became very important foods in the subsequent Late Archaic period. There is also an increase in the size of groups of people and a trend for population growth which continues throughout subsequent periods. The evidence for the population increase comes from the recording of larger occupation sites liberally strewn with fire cracked rocks from use in cooking with many fire and roasting pits and more evidence of human deaths and burial ceremony. Perhaps people were living at sites for several months with some year-round occupations of base settlements within environmentally productive zones. Heavily occupied base settlements have numerous fire pits, storage and roasting pits and extensive refuse accumulations called middens. People were no doubt building houses on these midden sites, but these are often impossible to detect in archaeological investigations. Why? Because the trash and all other cultural materials left behind are often mixed by overlapping pits and repeated digging by humans and animals in the soft organic midden soil. In affect, we don't know how big the houses were or how many were located at the base camps.

During this period of higher than normal temperatures and changing habitats in surrounding areas, perhaps the hill country of the Hoosier National Forest was a refuge area, as it probably was at the close of the Ice Age, but especially now that heavy forestation acted to cool the local temperatures. It was probably an attractive place to live, at least on a seasonal basis, to avoid the summer heat by camping in the ravines that open to the Ohio River.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

9/hoosier/prehistory/sec3.htm Last Updated: 21-Nov-2008 |