|

WRANGELL-ST. ELIAS

A History of the Chisana Mining District, Alaska, 1890-1990 |

|

Chapter Five

THE AFTERMATH

Starting in the late 1940s, hunting guides established headquarters in Chisana City, and its population slowly began to grow. Donald O. Spaulding, for example, was operating out of the community in 1947. [1]

Despite the influx of new residents, one pioneer remained a full time inhabitant. Occupying a small cabin at the southwest corner of the airstrip, N. P. Nelson ended the decade distributing the mail delivered by Cordova Air. [2]

Mining continued during the 1950s, though on an increasingly smaller scale. By the middle of the decade virtually all of the district's original claims had lapsed. Many, however, were eventually restaked by new operators employing mechanized equipment.

Several of the district's earliest residents still frequented Chisana City. Billy and Agnes James, for example, continued to spend much of their time in the community. [3] So did Shushana Joe, who lived there until his death in about 1960. [4]

|

| Fig. 41. A surviving section of an elaborate Bonanza flume, 1987. NPS photo. |

N. P. Nelson finally left Alaska in the mid-1950s, although he visited briefly in 1959. When the 96-year-old Nelson died in the mid-1960s, friends Ivan Thorall and Iver Johnson arranged to have his body cremated and his ashes returned to the district. Fittingly, the pair buried them on a prominent point above upper Bonanza Creek. [5]

Local residents submitted their first homestead applications about this same time, roughly dividing the Chisana townsite between two groups. Billy James filed on the eastern half in 1955, but died in Anchorage in 1960 before acquiring title. In 1962 guide Kenneth L. Folger sought the same spot, but never completed the necessary paperwork. Paul Jovich applied in 1968. He completed the process, receiving patent to the 18.5-acre site in 1979. Most of this property now belongs to guide Raymond A. McNutt. [6]

In 1957 Lou Anderton filed on the western half of the townsite. Unfortunately, Anderton, like James, died before his paperwork was approved. Herbert H. "Bud" Hickathier staked the site in 1964, but he also suffered an untimely death. [7]

Two other residents also claimed local land. Elizabeth Hickathier filled on an 80-acre trade and manufacturing site about two miles west of the Chisana townsite in 1964; and Ivan Thorall applied for a 130-acre homestead south of Chathenda Creek in 1967. Both were ultimately approved. [8]

|

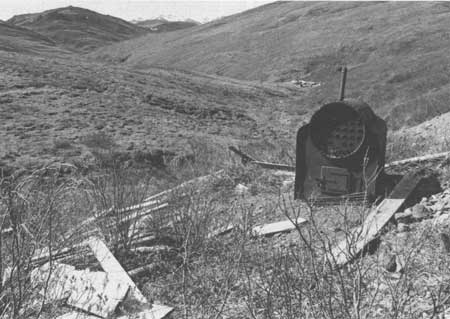

| Fig. 42. An abandoned mining boiler, 1987. NPS photo. |

Conflicting provisions contained in Alaska's Statehood Act eventually stifled the growing demand for Chisana land. The act allowed Alaska to select 103.5 million acres from the public domain, but forbid it from choosing any land claimed by the state's indigenous population. Alaska maintained that the provision only applied to land which the Natives had physically occupied. The Natives, however, insisted that it also included the land they traditionally used for subsistence activities. Predictably, these opposing interpretations soon clashed. [9]

When Alaska refused to modify its stand, the Natives asked the Interior Department to withdraw its tentative approval of the state's land selections. [10] Ultimately, Interior Secretary Stewart Udall went even further. On January 17, 1969, he closed entry on all of Alaska's federal lands until the Native claims question had been satisfactorily resolved. [11] Congress eventually settled the issue on December 18, 1971, with its passage of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA). [12]

Alaska's Native communities were not the only group to profit from the land claims struggle. Environmental organizations benefited as well. ANCSA authorized the interior secretary to withdraw up to eighty million acres in Alaska, for study toward their potential inclusion in national parks or forests, wildlife refuges, or wild and scenic river corridors. [13]

This provision eventually led to enactment of the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act of 1980 (ANILCA), placing 104.3 million acres of the state under permanent federal protection. Among those selected were the 13.2 million acres now contained in Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve. Therefore, the western half of Chisana City townsite, like most of the adjoining district, still remains in federal hands. [14]

Some mining, however, continues. ANILCA did not invalidate existing claims and many remain in effect. Not surprisingly, persistent operators like James A. Moody and Mark A. Fales still work Bonanza and Big Eldorado Creeks. The psychological heirs of Billy James and N. P. Nelson, these miners continue their predecessors' quest, ever searching for that one rich strike.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

wrst/chisana/chap5.htm

Last Updated: 21-Mar-2008