|

YELLOWSTONE

Trailside Notes (Number One) |

|

TRAILSIDE NOTES

I. Mammoth to Norris

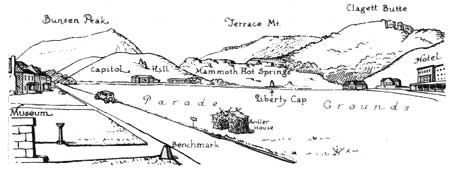

We meet at the Museum at Mammoth. We note that the "Bench Mark" shows an altitude of 6,239 feet. We identify the surrounding mountains—particularly Terrace Mountain and Mount Everts. We set our mileage at zero and drive to Liberty Cap.

NOTE: The text is arranged in three columns. Objects on the tourists' right are described on the right-hand side of the page; those on the tourists' left, on the left-hand side. Objects in front and general descriptions occupy the middle of the page.

Due to changes in the road, distances as given are only approximately correct. Government markers by the roadside give more exact distances.

Web Edition Note: Due to numerous changes in the years since this guidebook was published, the text should solely be used for historical purposes.

| MILEAGE | MILEAGE | |||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

|

0.4 (At the left) CAPITOL HILL A huge mass of glacial gravel resting upon the terrace material, or travertine. | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

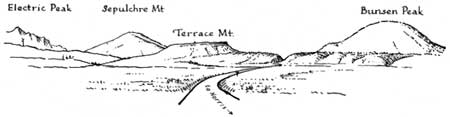

| Bunsen Peak (directly in front) is a huge mass of lava, and was named

for the inventor of the Bunsen Lamp. Bunsen gave the first plausible

theory of geyser action.

|

||||||||||||||

| 1.3 We are climbing out of the valley of the Gardiner River. | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| 2.7 |

TRAIL TO SNOW PASS CROSSING We now pass through a growth of Aspens. These trees are related to the Cottonwood and Poplar. The bark is a favorite food of the beaver and elk. | 2.7 | ||||||||||||

| 3.* A nearer view of Bunsen Peak shows that it is scored by landslides. In the distance far to the east are seen the rounded peaks of the Washburn Group. | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

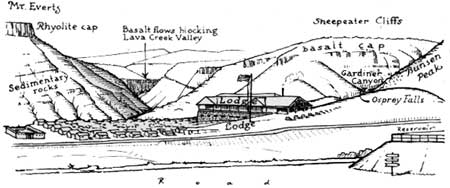

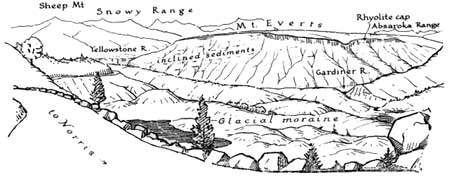

| 3.5 | Stop at Siding. At right a bank of coarse gravel. At left the entire floor of the valley is covered with stones and other material as though it had been a dumping ground. The small ponds are surrounded by hills of gravel. To the north Sheep Mountain and other peaks of the Snowy Range. Look way across the valley at Mount Everts and note the oblique lines or strata. These indicate the layers of sediment which formed on the bottom of an arm of the ocean when this part of the country was submerged. At that time there were no birds or mammals, like those of today, and, of course, no human beings. Much later came flows of lava. One of these can be seen as a thin cap over the southern end (right) of the mountain. | 3.5 | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| On the horizon, at the left of Bunsen, the peaks of the Washburn Group

again appear as rounded hills.

| ||||||||||||||

| 3.9 |

SILVER GATE AND THE HOODOOS Approaching Silver Gate we are abruptly confronted with a picturesque mass of huge blocks of stone. This is a gigantic landslide and we will presently see whence it came. The charred trunks are the ghost of a forest destroyed by fire. Young trees are beginning to spring up. | 3.9 | ||||||||||||

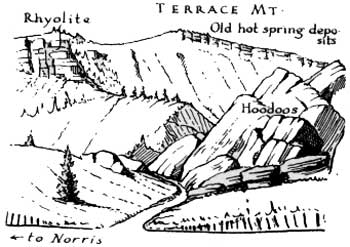

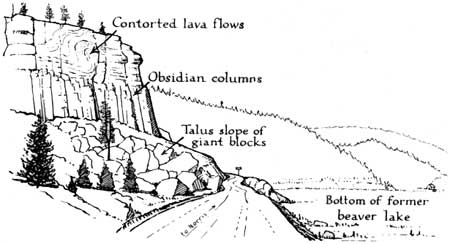

| 4.2 |

THE RHYO-TRAVERTINE GULCH These whitish angular rocks may be traced to the top of Terrace Mountain where they form a distinct layer. At some remote time hot springs were active on the crest of this mountain and their limy deposits covered a wide area to a considerable depth. The brownish rock on which the travertine rests is rhyolite, the same kind of rock that crowns Mount Everts. It appears that at one time the entire valley below was filled to the height of Mount Everts and that layers of molten rock flowed across this ancient surface. Upon cooling this lava hardened into the brownish rhyolite of today. After long periods of erosion hot springs deposited successive layers of travertine. Eventually glaciers descended from the south and west, overriding the old hot spring formations, carrying rocks and gravel, remnants of which may be found resting upon the travertine of Terrace Mountain. As the ice moved down valley blocks of travertine and rhyolite were broken off and plucked from the mountainside. As these rocks were shoved, rolled and dragged along, they were worn down and mixed up and finally—on the melting of the ice—they were left as hillocks of coarse gravel and boulders which we passed on our way up from Mammoth. Here, near their origin, the travertine blocks and rhyolite boulders have not begun to mingle. BUNSEN PEAK The configuration of this mass of volcanic rock and its composition (dacite rather than rhyolite) are evidences that it was intruded in a semi-molten state from hot layers of the earth's crust. From the fact that when we ascend the canyon we will find that the layers of rhyolite apparently flowed against its flanks it is evident that Bunsen Peak must have been well established long before. While here in the gulch let us review the sequence of geological events. 1. Bunsen Peak was intruded as a stock. 2. Erosion of surrounding area established Bunsen Peak. 3. Rhyolite flowed against its flank and across the valley. 4. Hot springs brought up lime from the deep-lying rocks and began to deposit it—as travertine—upon the upper layers of rhyolite. 5. Glaciers of the Ice Age—twenty or thirty thousand years ago—tore off and transported both travertine and rhyolite. 6. Hot springs continued to deposit travertine—they were not extinguished by the ice. 7. Present-day vegetation and climatic agencies are wearing away the picturesque landscape in a tireless effort to reduce everything to a level of uniformity. We enter and ascend Golden Gate Canyon and in doing so pass upward through the thick layers of rhyolite already observed. We are literally walled in by them. From the varying colors and structure of these frowning walls we conclude that they result from several distinct volcanic flows. | 4.2 | ||||||||||||

| 4.9 | We pass through Golden Gate—so named because of the brilliant yellow of an encrusting lichen (one of the lower plants) and emerge on Swan Lake Flat. | 4.9 | ||||||||||||

| At the left is a road around Bunsen Peak. (A fascinating drive down the Gardiner River—the canyon of which is lined with lava that has cooled into a marvelous series of columns—past Osprey Falls and back to Mammoth.) | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| 5.8 |

SWAN LAKE PANORAMA We stop and take in a wonderful panorama. Swan Lake Flat was once the bottom of a large lake, surrounded by banks, terraces and hillocks. The hills are largely composed of the same kind of glacial debris that made Capitol Hill, and was seen covering the valley of Gardiner River. The glacier which arose on the mountains at the west (Gallatin) was of relatively late occurrence and must have been a big one. | 5.8 | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

|

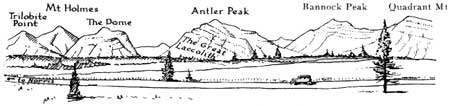

The surrounding mountain peaks are as follows: At the rear, (N.E.) Bunsen, at the left of which is the light gray crust of Terrace Mountain. Farther removed is the rounded, partially wooded, Sepulcher Mountain, and still farther the jagged Electric Peak, hardened by many igneous intrusions. A small cap of rhyolite on the top of Bunsen Peak suggests that rhyolite flows may have reached as high as its summit. To the Southwest are four apparently united peaks. The one at the left is Trilobite Point, so-called because trilobites—fossils of crustacean-like animals—have been found in the rocks of this mountain. The second is named for an eminent scientist, who gave the first geological description of the park, Dr. W. H. Holmes. On its summit a small "lookout" can be seen. The remaining two peaks in this group form Dome Mountain. Further to the right, Antler Peak stands quite alone. The long ridge extending from Antler toward Electric is Quadrant Mountain. The peaks from Trilobite to Electric mark the crest of the Gallatin Range. Ten miles to the west of this range is the Gallatin Highway. Toward the east—on the distant skyline and south of Bunsen Peak—are a series of elevations that mark the location of the Washburn Group, Mount Washburn, Tower Falls and Camp Roosevelt lie beyond this ridge. | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

|

Swan Lake is all that is left of a large lake that once covered this level area. The rare Trumpeter Swan is nesting here. Please do not disturb them. If you wish to know the names of birds, flowers, trees, etc., you should visit the Trailside Museums and Field Exhibits located at various points on the "loop." Proceed slowly. The middle distance is covered by Lodgepole pines. In the foreground are low hillocks and ridges of glacial gravel and volcanic rock. | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

|

Geologists tell us that the entire area that we now call the Rocky Mountains was the bed or beds of shallow seas and as the sedimentary layers were lifted, they emerged from the ocean and the eroded remains, which lie before us, now are eight or nine thousand feet above the present sea level. During this process the horizontal layers have been tilted, folded and cracked. Volcanic rocks have been intruded. Crests and peaks have been worn away, valleys have been formed and molten lava has repeatedly flowed up from below covering the surface as we have already seen. | ||||||||||||||

| 8.2 A road leads to the Basaltic Amphitheatre, on the left, one-fourth mile away, and well worth a visit. | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| 12 The yellow water lily grows in this small lake which is gradually being filled with encroaching vegetation and silt. | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

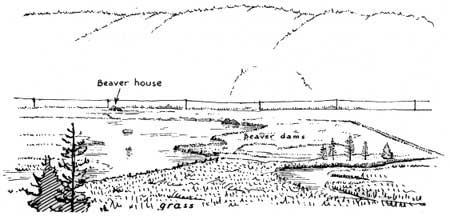

| 15

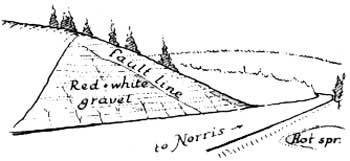

The Geologist reads this gravel bank as follows— 1. At the close of the Ice Age the valley of Obsidian Creek was a lake. 2. A stream from the uplands flowed into this lake. 3. At first the stream brought fine sediment which was deposited as clay, and now forms the base of the bank. If you examine the clay carefully you will find that it was deposited in layers. 4. On top of the clay is a brownish band of fine gravel. Something must have happened upstream. It looks as though hot springs had broken out somewhere and iron and sulphur had solidified and stained the gravel. | ||||||||||||||

| 15.1 5. Since "the more rapid the flow the larger the pebbles" we conclude that the streams emptying into the lake must have had varying velocities. 6. The colored (red) bank a little farther on gives positive proof that—after rivers deposit sand and gravel—hot springs, bearing iron and other coloring matter, may come into existence. The oblique line is evidence that underlying strata have moved a little and made a "fault line"—that a miniature earthquake occurred. | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

|

8. We conclude that hot chemical vapors are active agents in disintegrating rhyolite. Remember this when you marvel at the depth of the canyon of the Yellowstone. 9. See how the disintegrated and dissolved rhyolite gathers into small heaps. 10. When it rains, this powdered rhyolite is carried off by the small streams. It starts on its long journey to the ocean. 11. In the ocean it settles down as sediment and thus nature transforms an igneous rock into one that is sedimentary. | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| 18.6 | NYMPH LAKE FIELD EXHIBIT | 18.6 | ||||||||||||

|

This is a most instructive spot. 1. At the left is an outcrop of our old friend—the rhyolite. 2. Through its cracks and crevices hot decomposing gases have arisen from below destroying its character and changing it into mineral substances of various texture and color. 3. The action is still going on. Look up at the left and see the stream and fumes. 4. As you climb the hillock, the soil becomes hot and around the vents you will find that, as the vapors cool, sulphur in fine, yellow crystals is being deposited. (Don t disturb, others too may want to see.) 5. Below us, on the right of the road, vapors are also rising. There is a boiling pool. 6. Some of the water in Nymph Lake doubtless filters down onto the hot underlying rocks and comes back superheated. | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| 19.1 More rhyolite. Altered at the far end as it approaches hot springs and steam vents. | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

|

Lodgepoles as far as you can see—millions of them. On the horizon

at the left rise the low mountains that we noted as comprising the

Washburn Group.

| ||||||||||||||

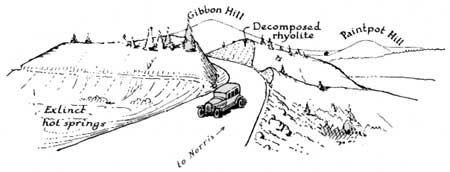

| 19.8 | The road now passes through a highly colored, whitish formation. Can it be that these hills are composed of mineral matter like Terrace Mountain that has been brought up from below by superheated water and stream? No. If we study this formation we find that the whitish banks along the roadside were originally composed of rhyolite, such as we have recently seen, but they have been decomposed into gravel and sand. Vapors of sulphur, and other gases have bleached the original darker lava and solutions of iron oxide and iron hydroxide have stained it yellow, red and pink. | 19.8 | ||||||||||||

| 20.6 |

NORRIS RANGER CAMP Here, at a concrete bridge, we meet the Gibbon River down the valley of which we will presently go until at Madison Junction it joins the Firehole River, and thus forms the Madison. The Madison empties into the Missouri at Three Forks, Montana. (The water travels more than four thousand miles before reaching the ocean at New Orleans.) Look around for elk. |

20.6 | ||||||||||||

| 20.9 | 20.9 | |||||||||||||

| Norris-Canyon freight road. Narrow, winding road, 25-mile speed limit. | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| 21.4 |

We bear to the right and suddenly come out on the rim of Norris Geyser Basin—"Nature's Laboratory." Here, through the agency of hot water, steam and other vapors, quartz and other mineral matter is being brought to the surface from be low and deposited as "sinter." Not only are the exposed hills of rhyolite being decomposed but the underlying rocks are yielding in this "chemical warfare." |

21.4 | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

|

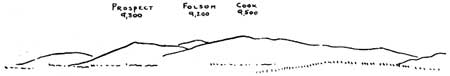

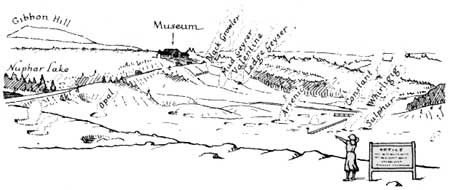

In the distance we again identify the mountains of the Gallatin Range. The profile from this angle is quite different from that heretofore seen. The lookout station identifies Holmes. The diagonal strata identify Antler and Quadrant. The dark area under the strata of Antler is a huge mass of once molten rock which was forced out of the earth, actually lifting the mountain and tilting it out of level. | ||||||||||||||

| Nuphar, a cool lake, considerably above the level of the basin. Why does it not drain into the basin? | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| 21.6 |

THE NORRIS TRAILSIDE MUSEUM Parking area on left beyond museum. You will add to the profit of your visit by spending some time examining the exhibits, reading the labels, referring to the relief map and conversing with the Ranger Naturalist. A half hour, self-guiding nature trail starts from the rear of the museum. It provides many interesting sights. |

21.6 | ||||||||||||

| <<< Previous | Next >>> |

trailside_notes/sec1-1.htm

Last Updated: 02-Apr-2007