|

YOSEMITE

Circular of General Information 1936 |

|

YOSEMITE

National Park

• OPEN ALL YEAR •

THE YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK is much greater, both in area and beauty, than is generally known. Nearly all Americans who have not explored it consider it identical with the far-famed Yosemite Valley. The fact is that the Valley is only a very small part, indeed, of this glorious public pleasure ground. It was established October 1, 1890, but its boundary lines have been changed several times since then. It now has an area of 1,176.16 square miles, 752,744 acres.

This magnificent pleasure land lies on the west slope of the Sierra Nevada about 200 miles due east of San Francisco. The crest of the range is its eastern boundary as far south as Mount Lyell. The rivers which water it originate in the everlasting snows. A thousand icy streams converge to form them. They flow west through a marvelous sea of peaks, resting by the way in hundreds of snow-bordered lakes, romping through luxuriant valleys, rushing turbulently over rocky heights, swinging in and out of the shadows of mighty mountains.

The Yosemite Valley occupies 8 square miles out of a total of 1,176 square miles in the Yosemite National Park. The park above the rim is less celebrated principally because it is less known. It is less known principally because it was not opened to the public by motor road until 1915. Now several roads and 700 miles of trail make much of the spectacular high-mountain region of the park easily accessible.

For the rest, the park includes, in John Muir's words, "the headwaters of the Tuolumne and Merced Rivers, two of the most songful streams in the world; innumerable lakes and waterfalls and smooth silky lawns; the noblest forests, the loftiest granite domes, the deepest ice-sculptured canyons, the brightest crystalline pavements, and snowy mountains soaring into the sky twelve and thirteen thousand feet, arrayed in open ranks and spiry pinnacled groups partially separated by tremendous canyons and amphitheaters; gardens on their sunny brows, avalanches thundering down their long white slopes, cataracts roaring gray and foaming in the crooked, rugged gorges, and glaciers in their shadowy recesses, working in silence, slowly completing their sculptures; new-born lakes at their feet, blue and green, free or encumbered with drifting icebergs like miniature Arctic Oceans, shining, sparkling, calm as stars."

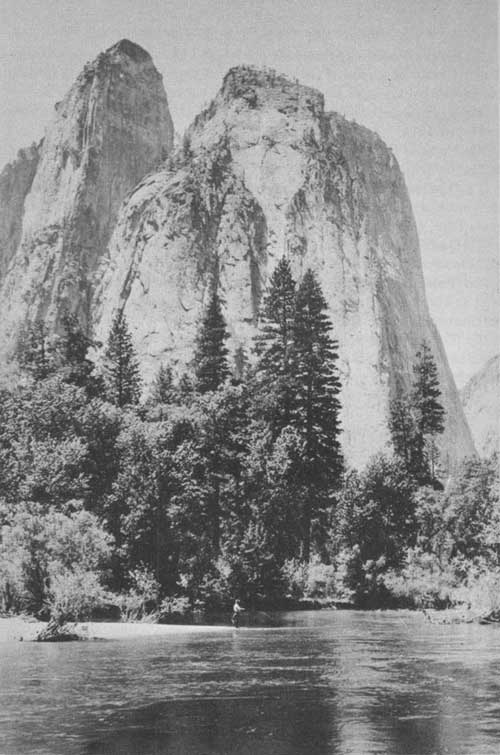

Fishing amid scenes of inspiring grandeur.

THE YOSEMITE VALLEY

Little need be said of the Yosemite Valley. After these many years of visitation and exploration it remains incomparable. It is often said that the Sierra contains "many Yosemites", but there is no other of its superabundance of sheer beauty. It has been so celebrated in book and magazine and newspaper that the Three Brothers, El Capitan, Bridalveil Fall, Cathedral Spires, Mirror Lake, Half Dome, and Glacier Point are old familiar friends to millions who have never seen them except in picture.

The Yosemite Valley was discovered in 1851 as an incidental result of the effort to settle Indian problems which had arisen in that region. Dr. L. H. Bunnel, a member of the expedition, suggested the appropriateness of naming it after the aborigines who dwelt there. It rapidly became celebrated.

No matter what their expectation, most visitors are delightfully astonished upon entering the Yosemite Valley. The sheer immensity of the precipices on either side of the Valley's peaceful floor; the loftiness and the romantic suggestion of the numerous waterfalls; the majesty of the granite walls; and the unreal, almost fairy quality of the ever-varying whole cannot be successfully foretold. The Valley is 7 miles long. Its floor averages 1 mile in width, its walls rising from 3,000 to 4,000 feet.

View of Yosemite Valley from Wawona Road Tunnel. Anderson photo.

HOW THE VALLEY WAS FORMED

After the visitor has recovered from his first shock of astonishment—for it is no less—at the beauty of the Valley, inevitably he wonders how nature made it. How did it happen that walls so enormous rise so nearly perpendicular from the level floor of the Valley?

When the Sierra Nevada was formed by the gradual tipping of a great block of the earth's crust 400 miles long and 80 miles wide, streams draining this block were pitched very definitely toward the west and with torrential force cut deep canyons. The period of tipping and stream erosion covered so many thousands of centuries that the Merced River was able to wear away the sedimentary rocks several thousand feet in thickness, which covered the granite, and then in the Yosemite Valley region to cut some 2,000 feet into this very hard granite. Meantime the north and south flowing side streams of the Merced, such as Yosemite Creek, not benefited by the tipping of the Sierra block, could not cut so fast as their parent stream and so were left high up as hanging valleys.

During the Ice Age great glaciers formed at the crest of the range and flowed down these streams, cutting deep canyons and especially widening them. At the maximum period the ice came within 700 feet of the top of Half Dome. It overrode Glacier Point and extended perhaps a mile below El Portal. Glaciers deepened Yosemite Valley 500 feet at the lower end and 1,500 feet opposite Glacier Point; then widened it 1,000 feet at the lower end and 3,600 feet in the upper half. The V-shaped canyon which had resulted from stream erosion was now changed to a U-shaped trough; the Yosemite Cataract was changed to Yosemite Fall. As the last glacier melted back from the Valley a lake was formed, the filling in of which by sediments has produced the practically level floor now found from El Capitan to Half Dome.

Visitors to the park should join an auto caravan to study evidences first hand and hear the story of the geology of Yosemite discussed by the ranger naturalists.

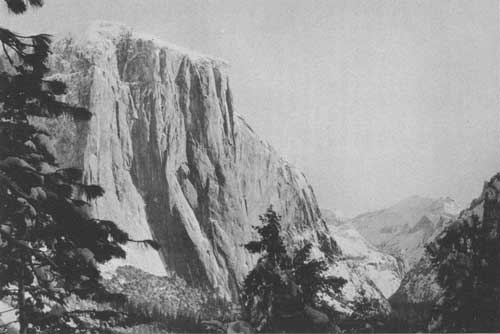

El Capitan rising 3604 feet above the floor of Yosemite Valley.

WATERFALLS

The depth to which the Valley was cut by streams and glaciers is measured roughly by the extraordinary height of the waterfalls which pour over the rim.

The Upper Yosemite Fall, for instance, drops 1,430 feet in one sheer fall, a height equal to nine Niagara Falls piled one on top of the other. The Lower Yosemite Fall, immediately below, has a drop of 320 feet, or two Niagaras more. Counting the series of cascades in between, the total drop from the crest of Yosemite Fall to the Valley floor is 2,565 feet. Vernal Fall has a drop of 317 feet; Illilouette Fall, 370 feet. The Nevada Fall drops 594 feet sheer; the celebrated Bridalveil Fall, 620 feet; while the Ribbon Fall, highest of all, drops 1,612 feet sheer, a straight fall nearly 10 times as high as Niagara. Nowhere else in the world may be seen a water spectacle such as this.

The falls are at their fullest in May and June while the winter snows are melting. They are still running in July, but after that decrease rapidly in volume, Yosemite Fall often drying up entirely by August 15 when there has been little rain or snow. But let it not be supposed that the beauty of the falls depends upon the amount of water that pours over their brinks. It is true that the May rush of water over the Yosemite Fall is even a little appalling, when the ground sometimes trembles with it half a mile away, but it is equally true that the spectacle of the Yosemite Fall in late July, when, in specially dry seasons, much of the water reaches the bottom of the upper fall in the form of mist, possesses a filmy grandeur that is not comparable probably with any other sight in the world; the one inspires by sheer bulk and power, the other uplifts by its intangible spirit of beauty. To see the waterfalls at their best one should visit Yosemite before July 15.

HEIGHT OF WATERFALLS

| Name | Height of fall |

Altitude of crest | |

| Above sea level |

Above pier near Sentinel Hotel | ||

| Feet | Feet | Feet | |

| Yosemite Fall | 1,430 | 6,525 | 2,565 |

| Lower Yosemite Fall | 320 | 4,420 | 460 |

| Nevada Fall | 594 | 5,907 | 1,947 |

| Vernal Fall | 317 | 5,044 | 1,084 |

| Illilouette Fall | 370 | 5,816 | 1,856 |

| Bridalveil Fall | 620 | 4,787 | 827 |

| Ribbon Fall | 1,612 | 7,008 | 3,048 |

| Widows Tears Fall | 1,170 | 6,466 | 2,506 |

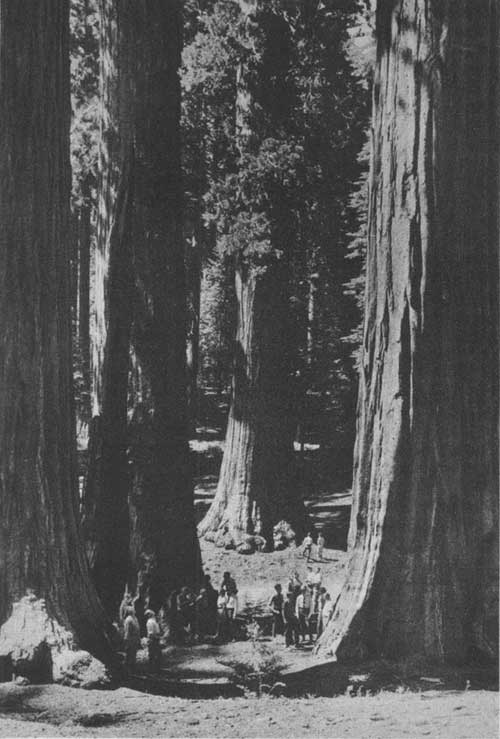

Ranger naturalists guide visitors in Mariposa Grove of Big Trees. Anderson

photo.

GLACIER POINT AND THE RIM OF YOSEMITE VALLEY

Glacier Point, above the Valley rim, commands a magnificent view of the High Sierra. Spread before one in panorama are the domes, the pinnacles, the waterfalls, and dominating all, Half Dome, a mythical Indian turned to stone. A few steps from the hotel one looks down into Yosemite Valley, 3,254 feet below, where automobiles are but moving specks, tents white dots, and the Merced River a silver tracery on green velvet. From the little stone lookout, perched on the very rim of the gorge, by means of high-powered binoculars installed for that purpose one may study the detail of the High Sierra and its flanking ranges, miles distant, through a sweep of 180°, as though they were at his very feet. A ranger naturalist is here in summer to assist visitors and to discuss the geology, trees, birds, and wildlife of Yosemite.

No visitor should leave Yosemite without seeing Glacier Point. It is the climax of all Yosemite views. It is reached by an excellent paved road which leaves the Valley just west of Bridalveil Fall, and then through the 4,223-foot tunnel to Chinquapin, from which point a good oiled mountain road leads through forests of fir and lodgepole pine to Glacier Point. The total distance is 28 miles, or about 1-1/2 hours' drive each way. The fire fall is a nightly feature and takes on an entirely different aspect from the top of the cliff. A short drive of a half mile from the main road above Glacier Point brings one to Sentinel Dome, 8,117 feet in elevation, where an unobstructed panorama of the southern half of the park may be had, from the coast range on the west to the snow-capped ridge of the Sierra on the east. A hotel, cafeteria, and Government camp ground are available at Glacier Point.

ALTITUDE OF SUMMITS ENCLOSING YOSEMITE VALLEY

| Name | Altitude above sea level |

Altitude above pier near Sentinel Hotel |

Name | Altitude above sea level |

Altitude above pier near Sentinel Hotel |

| Feet | Feet | Feet | Feet | ||

| Basket Dome | 7,602 | 3,642 | North Dome | 7,531 | 3,571 |

| Cathedral Rocks | 6,551 | 2,592 | Old Inspiration Point | 6,603 | 2,643 |

| Cathedral Spires | 6,114 | 2,154 | Panorama Point | 6,224 | 2,264 |

| Clouds Rest | 9,930 | 5,964 | Profile Cliff | 7,503 | 3,543 |

| Columbia Rock | 5,031 | 1,071 | Pulpit Rock | 4,195 | 765 |

| Eagle Peak | 7,773 | 3,813 | Sentinel Dome | 8,117 | 4,157 |

| El Capitan | 7,564 | 3,604 | Stanford Point | 6,659 | 2,699 |

| Glacier Point | 7,214 | 3,254 | Taft Point | 7,503 | 3,543 |

| Half Dome | 852 | 4,892 | Washington Column | 5,912 | 1,952 |

| Leaning Tower | 5,863 | 1,903 | Yosemite Point | 6,935 | 2,975 |

| Liberty Cap | 7,072 | 3,112 | |||

THE BIG TREES

One of the best groves of giant sequoia trees outside of the Sequoia National Park is found in the extreme south of the Yosemite National Park and is called the Mariposa Grove. It is reached from the Wawona Road, which enters the park from the south. From the Yosemite Valley it is an easy drive of 35 miles over a paved, high-gear road requiring about 1-1/2 hours each way. Unsurpassed views of the whole expanse of Yosemite Valley may be had from the east portal of the new 4,223-foot tunnel and, from the Wawona Road, an extensive outlook over the South Fork Basin and 4 or 5 ranges of foothills of the Sierra is a sight long to be remembered, especially at sunset when the mountain ranges turn to many shades of purple and gray.

All visitors to the Mariposa Grove should take the side trip to Glacier Point, a distance of 16 miles each way, the road branching off at Chinquapin. Here one may obtain an unsurpassed panorama of the High Sierra.

The new Big Trees Lodge in the upper grove is located in a beautiful grove of sequoias, 20 to 30 feet in diameter, and affords excellent accommodations, with cafeteria service available to all. The Government provides a public camp ground near the entrance to the Big Tree Grove. Hotels and camp grounds are also available at Wawona, 9 miles north of the grove on the Wawona Road. Stages are run daily throughout the summer to Glacier Point, Wawona, and Big Trees. Visitors to the grove are urged to take plenty of time and really grasp the significance of these giant trees, the oldest and largest living things on earth.

The Grizzly Giant is the oldest tree in the grove, with a base diameter of 27.6 feet, girth of 96.5 feet, and height of 209 feet. There is no accurate way of knowing the age of the Grizzly Giant but its size and gnarled appearance indicate that it is at least 3,800 years old.

A ranger naturalist is on duty at the Big Trees Museum and gives talks on the trees. Near the museum is the fallen Massachusetts tree, an immense sequoia, 280 feet long and 28 feet in diameter, that was blown over in the winter of 1927. As the tree is broken into several sections, it provides a fine opportunity to study the rings and the character of the wood. By climbing the length of this fallen tree one receives a graphic impression of the size of these monarchs. In August 1934 another giant, the "Stable" tree fell. It is located just above the museum. Visitors should continue up the road to the famous tunnel tree, the Wawona, and drive through the opening 8 feet wide that was cut in 1881. This tree is 231 feet tall and 27-1/2 feet in diameter. A little farther up the road a wonderful view over the Wawona Basin and South Fork Canyon may be had at Wawona Point, elevation 6,890 feet; especially fine are the views at sunset.

There are two other groves of Big Trees in Yosemite. The Tuolumne Grove, located on the Big Oak Flat Road, 17 miles from the Valley, contains some 25 very fine specimens and also a huge tree 29-1/2 feet in diameter through which cars may be driven. The other grove, one of unusual natural beauty in a secluded corner of the park, is the Merced Grove of Big Trees, reached by a good dirt road. It is about 5 miles west of Crane Flat off the Big Oak Flat Road.

THE WAWONA BASIN

The Wawona Basin of 14 square miles, added to the park in 1932, provides an extensive area for recreational use. Here camping, riding, and golfing may be enjoyed in a perfect setting along the South Fork of the Merced River. Wawona is located in a beautiful mountain meadow on the new Wawona Road, 27 miles south of the Valley and near the Mariposa Grove of Big Trees. Superb views are obtainable from many points on this road, which leaves the Valley just west of Bridalveil Fall. Saddle and pack animals are available at popular prices for trips to the fine fishing lakes and streams in the southern part of the park. There are also tennis courts and swimming pools. The Wawona Hotel provides both European and American plan service, and operates a coffee shop. Stores, meat market, garage, gas station, and post office are available, and along the river near Wawona is a free camp ground.

HETCH HETCHY VALLEY

A good oiled mountain road makes the scenic Hetch Hetchy Valley a short, 2-hour drive by car from Yosemite Valley, a distance of 38 miles each way over the Big Oak Flat Road. This road is a 1-way control road for the first 4 miles after it leaves the Valley near El Capitan. This one-way section is a road of rare charm and beauty with superb views over the Valley. It passes through fine stands of Sugar Pine and Red Fir and the Tuolumne Grove of Big Trees.

A fine paved road extends from Mather down to the Hetch Hetchy Dam, a distance of 9 miles, where one may see San Francisco's gigantic 300-foot Hetch Hetchy Dam and Water supply. The valley is similar to Yosemite, with tumbling waterfalls and precipitous cliffs surrounding a lake 7 miles long. The San Francisco Recreation Camp is located at Mather, near the park line.

Visitors using the Big Oak Flat Road are urged to see the wonderful panorama of the High Sierra from the fire lookout tower, 1-1/2 miles over an oiled road just west of Crane Flat. The fire guard on duty will be glad to explain the points of interest and show visitors how fires are located and put under control.

TUOLUMNE MEADOWS

John Muir, in describing the upper Tuolumne region, writes:

It is the heart of the High Sierra, 8,500 to 9,000 feet above the level of the sea. The gray, picturesque Cathedral Range bounds it on the south; a similar range or spur, the highest peak of which is Mount Conness, on the north; the noble Mounts Dana, Gibbs, Mammoth, Lyell, Maclure, and others on the axis of the range on the east; a heavy billowy crowd of glacier-polished rocks and Mount Hoffmann on the west. Down through the open sunny meadow levels of the valley flows the Tuolumne River, fresh and cool from its many glacial fountains, the highest of which are the glaciers that lie on the north side of Mount Lyell and Mount Maclure.

A store, gas station, garage, post office, camp ground, High Sierra Camp, and Tuolumne Meadows Lodge make the Meadows an ideal high-mountain camping place and starting point for fishing, hiking, and mountain-climbing trips. Tuolumne Meadows is 67 miles or about a 4-hour drive over the Big Oak Flat and Tioga Roads from Yosemite Valley. Saddle horses are available, and many fine trips may be made to Waterwheel Falls, Mount Lyell, Mount Conness, Glen Aulin, Muir Gorge, and hundreds of good fishing lakes and streams. Stage service to Tuolumne Meadows, Tioga Pass, Mono Lake, and Lake Tahoe is maintained daily through out the summer months.

Fishing is usually very good in nearby lakes and streams. The Waterwheel Falls, Muir Gorge, the Soda Springs, the spectacular canyon scenery, jewellike Tenaya Lake, and the Mount Lyell Glacier are a few of the interesting places to visit near Tuolumne Meadows.

John Muir writes this interesting description of the Grand Canyon of the Tuolumne and Waterwheel Falls:

It is the cascades or sloping falls on the main river that are the crowning glory of the canyon, and these, in volume, extent, and variety, surpass those of any other canyon in the Sierra. The most showy and interesting of them are mostly in the upper part of the canyon above the point of entrance of Cathedral Creek and Hoffmann Creek. For miles the river is one wild, exulting, onrushing mass of snowy purple bloom, spreading over glacial waves of granite without any definite channel, gliding in magnificent silver plumes, dashing and foaming through huge boulder dams, leaping high in the air in wheellike whirls, displaying glorious enthusiasm, tossing from side to side, doubling, glinting, singing in exuberance of mountain energy.

Muir's "wheellike whirls" undoubtedly mean the celebrated Waterwheel Falls. Rushing down the canyon's slanting granites under great headway, the river encounters shelves of rock projecting from its bottom. From these, enormous arcs of solid water are thrown high in the air. Some of the Waterwheels rise 20 feet and span 50 feet in the arc. Unfortunately, the amount of water in the river drops with the advance of summer and the Waterwheels lose much of their forcefulness. Visitors should see this spectacle during the period of high water from June 15 to August 1 in normal years.

The Waterwheel Falls may be reached by a good trail 5.5 miles from the Tioga Road down the Tuolumne River Gorge to the Glen Aulin High Sierra Camp, where meals and overnight accommodations are available, then 2.8 miles down the river to Waterwheel Falls. Saddle animals may be rented at Tuolumne Meadows for this trip.

Below the Waterwheels the Tuolumne Canyon descends abruptly, the river plunging madly through the mile-deep gorge. Trails built a few years ago down the canyon from the Waterwheel Falls to Pate Valley penetrate the very heart of the gorge. The Muir Gorge, a vertical-walled cleft in the canyon a half mile deep, is, as a result, but 2 hours below Waterwheel Falls and the same above Pate Valley by the new trails. The entire canyon may be traversed with ease either on horseback or on foot.

PATE VALLEY

A few miles farther westward the granite heights slope back more gently and the river suddenly pauses in its tumultuous course to meander through the pines and oaks and cedars of a meadowed flat. Pate Valley has been known for years from the reports of venturesome knapsackers, but now it is made accessible by one of the best trails in the park.

An unnatural smoky blackening of the overhanging cornices of the 200-foot walls almost surrounding the glade leads one to approach them, and there, near the ground, are hundreds of Indian pictographs. These are mysterious, fantastic, and unreadable, but the deep-red stain is as clearly defined as on the day that the red man set down tales of his great hunt, or of famine, or of war, or perhaps of his gods. Here, too, obsidian chips tell the story of preparation for war and the chase, and sharp eyes are rewarded by the sight of many a perfect spear point or arrowhead.

Atop a huge shaded talus block are many bowl-shaped holes, a primitive gristmill where once the Indian women ground acorns for their pounded bread, which was the staff of life for so many California tribes. Blackened cooking rocks may be found, and numerous stone pestles lying about in this and two or three similar places seem to point to a hurried departure, but the "when" and "why" of this exodus still remain a mystery.

THE NORTHERN CANYONS

North of the Tuolumne River is an enormous area of lakes and valleys which are seldom visited, notwithstanding that it is penetrated by numerous trails. It is a wilderness of wonderful charm and deserves to harbor a thousand camps. The trout fishing in many of these waters is unsurpassed.

Though unknown to people generally, this superb Yosemite country north of the Valley has been the haunt for many years of the confirmed mountain lovers of the Pacific coast. It has been the favorite resort of the Sierra Club during many years of summer outings.

THE MOUNTAIN CLIMAX OF THE SIERRA

The monster mountain mass, of which Mount Lyell. 13,090 feet high, is the chief, lies on the eastern boundary of the park. It may be reached by trail from Tuolumne Meadows and is well worth the journey. It is the climax of the Sierra in this neighborhood.

The traveler swings from the Tuolumne Meadows around Johnson Peak to Lyell Fork and turns southward up its valley. Huge Kuna Crest borders the trail's left side for miles. At the head of the Valley, beyond several immense granite shelves, rears the mighty group, Mount Lyell in the center, supported on the north by Mount Maclure and on the south by Rodgers Peak.

The way up is through a vast basin of tumbled granite, encircled at its climax by a titanic rampart of nine sharp, glistening peaks and hundreds of spear-like points, the whole usually cloaked in enormous sweeping shrouds of snow. Presently the granite spurs enclose one. And directly beyond these looms a mighty wall of glistening granite which apparently forbids further approach to the mountain's shrine. But another half hour brings one face to face with Lyell's rugged top and shining glacier, one of the noblest high places in America. Mount Dana, with its glacier and great variety of alpine flowers, can be climbed in one day from Tuolumne Meadows and now offers a very popular hiking trip.

MERCED AND WASHBURN LAKES

The waters from the western slopes of Lyell and Maclure find their way, through many streams and many lakelets of splendid beauty, into two lakes which are the headwaters of the famous Merced River. The upper of these is Washburn Lake, cradled in bare heights and celebrated for its fishing. This is the formal source of the Merced. Several miles below, the river rests again in beautiful Merced Lake.

One of the six Yosemite High Sierra camps is at the head of Merced Lake. There is a new trail 13 miles from Yosemite Valley to Merced Lake which crosses glacier-polished slopes. It is real wilderness, famous for its good fishing and beautiful scenery.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

1936/yose/sec2.htm

Last Updated: 20-Jun-2010