|

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

The Secret of the Big Trees |

|

THE SECRET OF THE BIG TREES.1

By ELLSWORTH HUNTINGTON.

Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

1This article appeared in the July, 1912, number of Harper's Magazine, and is reprinted here in a revised form with the addition of photographs of some of the big trees in the national parks. The field work was necessarily carried on in areas outside the parks, as no timber is cut within the reservations—Editor.

In the days of the Prophet Elijah sore famine afflicted the land of Palestine. No rain fell, the brooks ran dry, and dire distress prevailed. "Go through the land," said King Ahab to the Prophet Obadiah, "unto all the fountains of water and unto all the brooks; peradventure we may find grass and save the horses and mules alive, that we lose not all the beasts." When Obadiah went forth in search of forage he fell in with his chief, Elijah, and brought him to Ahab, who greeted him as the troubler of Israel. Then Elijah prayed for rain, according to the Bible story, and the famine was stayed.

From this famine in Palestine, some 870 years before Christ, to the forests of the Sierra Nevadas, in the year of grace 1911, is a far cry. The idea of investigating an episode of ancient Asiatic history in the mountains of California seems at first sight quixotic. Yet for the purpose of facilitating such an investigation the Carnegie Institution of Washington furnished funds, and Yale University gave the author leave of absence from college duties. The men in charge of both institutions realize that the possibilities of any line of research bear no relation whatever to its immediate practical results, or even to its apparent reasonableness in the minds of the unthinking. The final outcome of any piece of scientific work may not be apparent for generations, but that does not make the first steps less important. Already, however, our results possess a positive value. They demonstrate anew that this world of ours, with all its manifold activities, is so small, and so bound part to part, that nearly 3,000 years of time and thrice 3,000 miles of space can not conceal its unity.

The connecting link between the past and the present, between the ancient East and the modern West, is found in the big trees of California, the huge species known as Sequoia washingtoniana. Everyone has heard of this tree's vast size and great age. The trunk of a well-grown specimen has a diameter of 20 or 30 feet, which is equal to the width of an ordinary house. Such a tree often towers 250 or 300 feet, or six times as high as a large elm, and within 50 feet of the top the trunk is still 10 or 12 feet in thickness. Three thousand fence posts, sufficient to support a wire fence around 8,000 or 9,000 acres, have been made from one of these giants, and that was only the first step toward using its huge carcass. Six hundred and fifty thousand shingles, enough to cover the roofs of 70 or 80 houses, formed the second item of its product. Finally there still remained hundreds of cords of firewood which no one could use because of the prohibitive expense of hauling the wood out of the mountains. The upper third of the trunk and all the branches lie on the ground where they fell, not visibly rotting, for the wood is wonderfully enduring, but simply waiting till some foolish camper shall light a devastating fire.

|

|

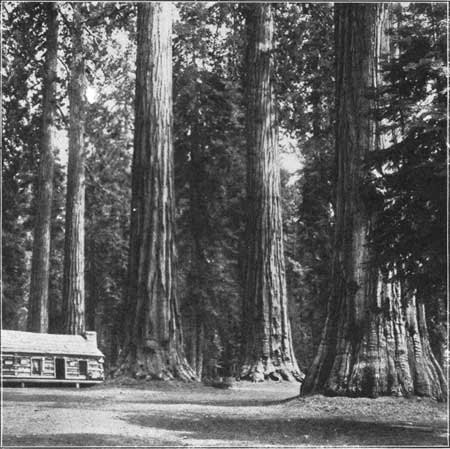

MARIPOSA GROVE,

YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK.

Photograph by Pillsbury Picture Co. The Mariposa Grove is situated in the southern portion of the Yosemite National Park, 35 miles from Yosemite Valley. There are two other groves of big trees in the Yosemite National Park—the Tuolumne Grove of 20 trees 17 miles northwest of Yosemite Valley and the Merced Grove of 40 trees 9 miles north west of Yosemite Valley. |

Huge as the sequoias are, their size is scarcely so wonderful as their age. A tree that has lived 500 years is still in its early youth; one that has rounded out 1,000 summers and winters is only in full maturity; and old age, the three score years and ten of the sequoias, does not come for 17 or 18 centuries. How old the oldest trees may be is not yet certain, but I have counted the rings of 79 that were over 2,000 years of age, of 3 that were over 3,000, and of 1 that was 3,150. In the days of the Trojan War and of the exodus of the Hebrews from Egypt this oldest tree was a sturdy sapling, with stiff, prickly foliage like that of a cedar, but far more compressed.

It was doubtless a graceful, sharply conical tree, 20 or 30 feet high, with dense, horizontal branches, the lower ones of which swept the ground. Like the young trees of to-day, the ancient sequoia and the clump of trees of similar age which grew close to it must have been a charming adornment of the landscape. By the time of Marathon the trees had lost the hard, sharp lines of youth, and were thoroughly mature. The lower branches had disappeared, up to a height of 100 feet or more; the giant trunks were disclosed as bare, reddish columns covered with soft bark 6 inches or a foot in thickness; the upper branches had acquired a slightly drooping aspect; and the spiny foliage, far removed from the ground, had assumed a graceful, rounded appearance. Then for centuries, through the days of Rome, the Dark Ages, and all the period of the growth of European civilization, the ancient giants preserved the same appearance, strong and solid, but with a strangely attractive, approachable quality.

After one has lived for weeks at the foot of such trees, he comes to feel that they are friends in a sense more intimate than is the case with most trees. They seem to have the mellow, kindly quality of old age, and its rich knowledge of the past stored carefully away for any who know how to use it. Often in the search for scientific information in remote parts of the world one comes to some primitive village and inquires whether there are not some old men of long experience who can tell the story of the past. So it is with trees; like old men, they cherish the memory of hundreds of interesting events, and all that is needed is an interpreter.

|

|

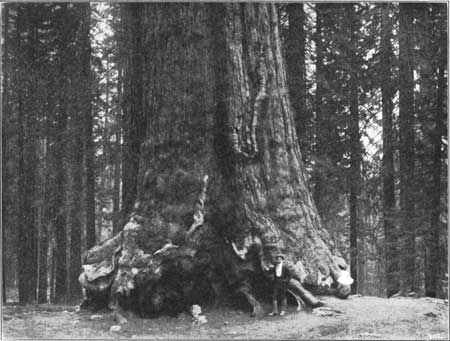

BASE OF GRIZZLY

GIANT, MARIPOSA GROVE, YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK.

Photograph by Pillsbury Picture Co. |

| <<< Previous | Next >>> |

huntington/sec1.htm

Last Updated: 12-Feb-2007