|

Field Division of Education Tuzigoot - The Excavation and Repair of a Ruin on the Verde River near Clarkdale, Arizona |

|

STONE TOOLS AND OTHER OBJECTS OF STONE

The quantity of stone tools and other articles of stone recovered in the course of the complete excavation of any prehistoric pueblo has some significance. Such quantitative statements are particularly valuable when the evolutionary development of tool types has been worked out in a region. In the case of the Upper Verde, the evolution of stone tool types has not been established but when it is, it will be worthwhile to know the proportions in which various types occurred at Tuzigoot.

Following is a tabulation of all the stone objects and their quantity as they were found in the excavation at Tuzigoot:

| CHIPPED STONE TOOLS | 419 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Arrowpoints | 323 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Points with stems | 138 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Points without stems | 136 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Undetermined types | 45 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Knives | 55 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| With cutting edges all around | 15 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| With two cutting edges | 22 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| With one cutting edge | 12 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pointed, hafted at one end | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spearpoints | 10 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Points without stems | 7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Points with stems | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Drills | 22 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| With worked bases | 11 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| With unworked bases | 11 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tomahawks | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Digging Tools | 6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| PECKED AND GROUND STONE TOOLS | 1,219 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Metates | 120 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heavy Mortars | 9 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Manos | 615 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Axes | 127 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Double-blade axes | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Single-blade axes | 59 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Axes used subsequently as mauls | 58 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Maul | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Picks | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Arrow-Shaft Reducers | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Arrow-Shaft Straighteners | 26 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Scrapers and Knives | 87 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| With concave blade | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Of irregular or rectangular form | 64 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| With specialized handles | 17 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pumice Mortars and Dishes | 27 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Small mortars | 21 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Large oval dishes | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Miniature metates | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Handled Grinders or "Pottery Anvils" | 52 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tapered handle without groove | 6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Flat type with groove | 13 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| True "anvil" type | 33 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pestles | 16 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| With long, tapered handles | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other types | 13 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Whetstones | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rubbing Stones | 30 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hammerstones | 18 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pemmican Pounders | 26 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stone Gouge | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Polishing Pebbles | 54 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| OTHER OBJECTS OF STONE | 34 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Palettes | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pipe, or Cloud—Blower (Straight) | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hatch-Cover | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Olla Lids | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ceremonial Objects | 25 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phallic symbols | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Miniature axes | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Painted pebble | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Plummet-shaped stone | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stone balls | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Quartz crystals | 13 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetite ball | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stone Discs | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stone Ring | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In addition to the tools and stone objects listed above, quantities of azurite, malachite, and hematite in both worked and unworked states were obtained in the excavation, as well as a number of fossils, concretions, stalactites and stalagmites, and other stones of peculiar or unusual formation. Many fragments of the raw materials from which the stone tools were made came to light. Many large pieces of red argillite commonly called pipestone, the raw material of much of the stone jewelry, were found on the floors of rooms and in the refuse accumulations. Large nodules of obsidian, jasper, and chert were of common occurrence.

CHIPPED STONE TOOLS

ARROWPOINTS. Very few points for arrows were made of any material other than black obsidian. Two hundred and eighty three out of a total of three hundred and twenty-three points were of obsidian. The majority of the points of materials. The obsidian points were fairly homogeneous in form and may be classified into two main groups. Because of damaged bases or edges, forty-two of them were not classifiable.

| A. Stemmed types | 115 | |||

| 1. Stem equal in width to shoulder, straight base | 35 | |||

| 2. Stem wider than shoulder, straight base | 42 | |||

| 3. Stem wider than shoulder, concave base | 14 | |||

| 4. Stem narrower than shoulder | 1 | |||

| 5. Aberrant forms | 3 | |||

| B. Plain base types | 144 | |||

| 1. Straight base, straight edges | 46 | |||

| 2. Straight base, convex edges | 16 | |||

| 3. Straight base, concave edges | 112 | |||

| 4. Straight base, serrate edges | 6 | |||

| 5. Concave base, straight edges | 18 | |||

| 6. Concave base, concave edges | 14 | |||

| 7. Concave base, serrate edges | 6 | |||

| 8. Aberrant forms, concave base | 3 | |||

The range in size for both the stemmed and plain base types is 1-5/8 inch length by 1/2 inch width to 1/2 inch length by 5/16 inch width. The variation in size in the plain base types is not so great as that in the stemmed types. The average size for obsidian points is about 7/8 inch length by 7/16 inch width.

Obsidian points occurred at all levels in the refuse accumulations surrounding the pueblo. The great majority of all points found were obtained by screening the refuse. Only nineteen were burial offerings.

There were thirty-eight arrowpoints made of materials other than obsidian The majority of these, 22 in all, were made of chalcedony of an opaque white variety. Other material used were grey chert, black flint, yellow jasper, and moss agate. They have been classified as follows:

| A. Stemmed types | 23 | |||

| 1. Stem narrower than shoulder | 12 | |||

| 2. Stem equal to shoulder, concave base | 5 | |||

| 3. Stem wider than shoulder, concave base | 4 | |||

| B. Plain base types | 10 | |||

| 1. Straight base, convex edges | 3 | |||

| 2. Straight base, straight edges | 1 | |||

| 3. Concave base, convex edges | 2 | |||

| 4. Concave base, straight edges | 3 | |||

| 5. Convex base, convex edges | 1 | |||

| C. Aberrant forms | 5 | |||

Attention should be called to the predominance of the stemmed type with stem narrower than the shoulder, a form which is of very rare occurrence in the obsidian points. The other forms, with the exception of the aberrant types, are all duplications of the forms occurring in the obsidian points.

SPEARPOINTS. The distinction between arrowpoints and spear points is mainly a matter of size. Arrowpoints have been considered to include all projectile points with a base less than 5/8 inch in width. It is purely an arbitrary distinction, but would seem to conform with the size of arrowshafts that have been noted in the Upper Verde region. A total of ten spearpoints was found in the excavation of Tuzigoot. Seven of these were made of black obsidian. Two were of stemmed types, the others of plain base types with straight or convex bases and convex edges.

One unfinished obsidian spearpoint was found with a burial. The others were found on the floors of rooms or in the refuse surrounding the pueblo.

KNIVES. Chipped tools that might be classified as knives or scrapers are here classified as knives, regardless of function. Fifty-five more or less complete specimens and fifteen fragments which were probably knives were found.

Of this total of seventy, forty were made of obsidian, four of yellow or brown jasper, nine of variously colored chalcedony, three of black flint, and one of red carnelian. With the exception of the fragments, they have been grouped as follows:

| A. Cutting edges all around and secondary chipping on major faces | 12 |

| B. Cutting edges all around with no secondary chipping | 1 |

| C. Two cutting edges, no secondary chipping | 22 |

| D. One cutting edge, no secondary chipping | 12 |

| E. Pointed, probably hafted at one end, secondary chipping | 8 |

The most numerous class, that with two cutting edges and no secondary chipping on major faces, varies in the matter of bevelling on the cutting edges. The majority are bevelled only on one side, both edges being bevelled from the same side. Another large group is bevelled on both sides of both edges. Two specimens are bevelled on both sides of one edge, on only one side of the other edge. No specimens show bevelling on the opposite sides of opposite edges.

The majority of all but the first and last groups are merely fortuitous flakers whose shape was not modified after the primary flaking.

Two of the single cutting edge forms and one of the double cutting edge form were found with a burial, together with a large quantity of unworked flakes, unfinished arrowpoints, and drills. The others were found scattered through the refuse and on the floors of rooms.

DRILLS. A total of twenty-two drills were found in the excavation. Fifteen of these were of black obsidian, the remainder of yellow and brown jasper, grey flint, chalcedony, and moss agate. They have been classified as follows:

| A. Worked base types | 11 | |||

| 1. Plain base | 1 | |||

| 2. Expanded tapering base | 6 | |||

| 3. Abruptly expanded base | 4 | |||

| B. Unworked base types | 11 | |||

| 1. Gradually expanded base | 6 | |||

| 2. Shouldered base | 5 | |||

The drills were found in the refuse and in the fill with two exceptions. One of the finest was found with an elaborate burial. Another was found with the collection of unworked flakes and unfinished chipped tools just mentioned as occurring with a burial.

TOMHAWK. A fine specimen of chipped tool or weapon was found on the floor of a room in Group I. It is very finely chipped over its whole surface and the edges and points are sharply and carefully retouched. It was made of black flint.

DIGGING TOOLS OR PICKS. Two somewhat similarly shaped tools were found which lack the careful finish and fine workmanship of the tomahawk just described. One was made of greenstone, the other of diabase.

Chipped tools at Tuzigoot were numerous and the workmanship was generally of a high standard. Some of the large knife blades and spearpoints show a good mastery of a chipping technique that produces a type of ripple-flaking comparable with Palaeolithic European Solutrean work. It is significant that the standard of chipped stone work was so high at Tuzigoot. It seems to mark the inhabitants of the pueblo off from the people of the northern Pueblo region, where chipping technique was generally of a very low order.

The material of overwhelmingly great importance in use for chipped tools was black obsidian. Other materials were only of very minor importance. Two large caches of obsidian flakes and small nodules of obsidian, indicating occurrence in a ledge from two to three inches in thickness, were found in another room. The largest nodule weighed one pound, three ounces. Similar nodules of yellow jasper and grey chert, of known local occurrence, were found, but neither material was in anything like the extensive general use for chipped tools that obsidian was.

PECKED AND GROUND STONE POOLS

METATES. All metates were of the troughed type. Scoriaceous basalt and fine grained red sandstone were in use as materials. All of the basalt metates were troughed with both ends open. Most of the sandstone metates were of similar form, but about one-third had only one end open.

A little less than half as many sandstone metates were in use as basalt metates. The former were rarely worked as deeply as the latter. Frequently a sandstone and a basalt, metate were found together in a room, but just as frequently there were two or more basalt metates and none of sandstone, There was no consistent association of sandstone metates with sandstone manos.

There was nothing to indicate the use of any special sort of props for the metates. Some were found embedded in the floors so that they rested at an angle of about twenty degrees with the floor. None were found resting on stones or other solid props. Several metates were troughed in such a way that they needed no end sup port to incline the trough at an angle to the floor, the bottom of the trough not being parallel with the base of the metate.

Six basalt and one sandstone metates were found which had originally served as ordinary troughed metates, with open ends. But they were subsequently modified into shallow mortars, by making circular depressions in the bottoms of the troughs. They are similar to one figured by Bartlett (1933), There was nothing to indicate that they represented any transitional form. They were found in some of the later rooms.

One basalt metate was found with the suggestion of a handle, consisting merely of a roughly formed rectangular projection on only one side.

MANOS. The great majority of manos were rectangular or roughly oval, with a single grinding surface and plano-convex in cross section. The upper surfaces in most cases had been pecked to shape. The materials in use were scoriaceous basalt and red sandstone. There were somewhat more basalt than sandstone manos. Average dimensions for manos was about 7x3-1/2x1-1/2 inches.

There was a small proportion of manos which varied from the above general type. In both basalt and sandstone materials there was a specially heavy type of mano, designed perhaps for two-handed coarse grinding. The average basalt mano of this type measured about 9 inches by 4 inches by 3 inches thick. The heaviest found weighed 14 pounds, 11 ounces. The heavy type sandstone manos averaged somewhat thinner and lighter. Sixteen of the heavy type basalt manos were found and thirteen of the heavy type sandstone.

Another variation in mano types, occurring in both sandstone and basalt, consisted of those with depressions packed on the sides for the accommodation of the fingers. Such depressions were common on the heavy type manos, but were not confined to them. The heaviest malapai mano with finger holds weighed 12 pounds, 9 ounces and the heaviest sandstone mano weighed 6-1/2 pounds. Eight inches was about average length. In thickness they varied from 4 inches to 1 inch. The finger grips consisted of grooves running the full length of the sides of the mano on both sides, or of grooves about 2 inches long in the center of the sides of the mano. They were rarely more than a quarter of an inch deep and were usually less than an inch wide.

Very few manos had more than a single grinding surface. Only three basalt manos showed evidence of having been used on two surfaces for grinding. One of these was definitely wedge-shaped, but it did not appear that the wedge-shape had been produced by wear. One surface showed much wear; the other very little. Probably the wedge-shape was more or less accidental, resulting from the original form of the pebble from which the mano was made. The other two basalt manos showing use of two grinding surfaces were of the usual form, except for being flat on two major surfaces.

Fourteen of the sandstone manos showed use of two or three surfaces for grinding. Five of these were wedge-shaped; three were triangular; and the rest were more or less rectangular in cross-section. The latter need no further consideration; they were merely the usual form of mano which by no special process had been unused on two surfaces. If any such evolutionary process in mano forms as that described by Bartlett (1933) was going on at Tuzigoot, it had not progressed very far. That then triangular form had appeared very early in the history of Tuzigoot is indicated by the finding of a very well-developed triangular sandstone mano in the deeper (6 foot level) strata of the refuse on the west slope. Perhaps the other two triangular manos and the five wedge-shaped ones represent similar isolated chance mutations, and not a definite trend, even at the late period of 1300 A.D., to the final stage of Pueblo mano evolution as described by Bartlett. It is worth emphasizing that the evolution to the three surface mano, if it can be considered an evolution, was going on at Tuzigoot only in the sandstone types. It is impossible to see the development of the mutation in the harder basalt forms.

As many as thirty-one manos of various types were found on the floor of a single room. On the average not more than twelve or fifteen, often about equally divided between sandstone and basalt, manos were found in a single room.

HEAVY MORTARS. A single large basalt mortar was found on the floor of Room 5, Group II, one of the early abandoned rooms of the pueblo.

In addition to the seven mortar-metates already mentioned, seven sandstone mortars came to light. With one exception, these were made from boulders ranging in diameter from 6 inches to 14 inches. The depressions were round or oval, roughly pecked, and none was more than 2 inches deep. The exceptional mortar was made of a flat slab of sandstone, about an inch and a half thick.

Mortars were obviously uncommon at Tuzigoot and played no important part in the corn-grinding apparatus of the pueblo.

AXES. The following table gives the number of the various types of axes found at Tuzigoot:

| Total of all types | 127 | ||||||||

| Double blade axes | 8 | ||||||||

| Single blade axes | 119 | ||||||||

| Single blade axes subsequently used as mauls | 58 | ||||||||

| With full groove | 4 | ||||||||

| With three-quarter groove | 54 | ||||||||

| With double groove | 5 | ||||||||

| With raised groove edges | 4 | ||||||||

| Single blade axes not used as mauls | 61 | ||||||||

| With full groove | 2 | ||||||||

| With three-quarte groove | 59 | ||||||||

| Long blade type | 9 | ||||||||

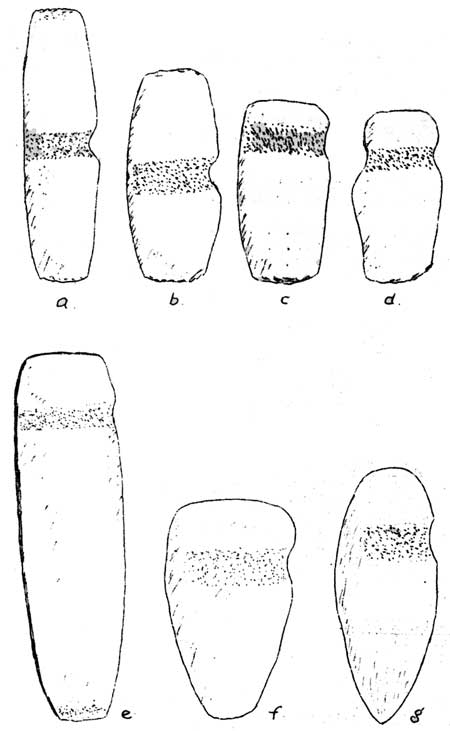

DOUBLE-BLADE AXES. The eight double-blade axes, (Fig. 11 a and b), were all very well made. Four were made of diorite; three of greenstone; and one of quartzitic red and black sandstone. All are three-quarter groove except one, which is full groove. A notable characteristic is that the grooves are without exception pecked, but unpolished, while the blades are all very well polished. The range in length is from 8-1/2 inches to 5 inches. The range in weight is from 1 pound 6 ounces to 11 ounces.

|

| Fig. 11. a and b. Double-blade axes with well sharpened edges. c and e. Three-quarter grove axes. d. Full groove axes. f and g. Picks. |

SINGLE-BLADE AXES. The sixty-one single-blade axes, (Fig. 11, c, d, e and f), which were not subsequently used as mauls were all made of diorite except one, which is of porphyritic basalt.

Fifty-nine have the three-quarter groove; two have the full groove. The two with the full groove are small crudely made specimens and obviously are not representative of a general type in use at Tuzigoot.

The three-quarter groove axes range in length from 10-1/2 inches to 3-1/4 inches; in width from 3-1/4 inches to 1-3/8 inches; in thickness from 2-1/4 inches to 3/4 inch; in weight from 5-1/4 pounds to 4 ounces.

The axes are not in general of a fine finish. More than half were polished in such a way that original irregularities were not ground smooth. Only five were polished completely and carefully over the whole surface. Eight were not polished at all.

In the majority of specimens the blade tapers slightly from groove to edge; in a small proportion the taper is pronounced. In the majority of those in which there is taper, the taper amounts to about a half inch from shoulder to edge.

The polls are almost all of the same length, about 1-1/4 inches, the difference in lengths of axes resulting from differences in the lengths of blade alone. In all the polls there is a slight taper on both the faces and the inner and outer sides. In specimens that show little use, the poll is squared off with a more or less flat surface. In such specimens, the ends are battered to a rounded form.

Grooves are generally shallow, often being about 1/16 inch deeper across both faces than across the outer side. The average depth of groove is about 1/8 inch.

The faces of axes are either flat or very slightly convex. The inner sides are as frequently flat as convex. No concave inner sides occur.

LONG BLADE AXES. There is one important variation from the general type of axe in use at Tuzigoot. This is the long blade type, (Fig. 11, e), of which there are nine specimens. Four of these were found in a single room in Group IV and perhaps represent the specialized activities of a single workman. The axes that have been placed in this group comprise those whose total length is over seven inches. In all respects except the extreme length of the blade relative to the length of the poll, they conform to the general type of then three-quarter groove axe at Tuzigoot. The polls are no longer than those of the ordinary small axe, being about 1-1/4 inches. The longest specimen has a blade 8-1/4 inches in length. In the others the length of the blade varies from 6-1/2 to 7-1/8 inches. The long blade axes are more often rectangular in crosssection than are the smaller axes.

AXES USED AS MAULS. Of the axes subsequently used as hammers or mauls there are four with the full groove. Three of these are crudely made tools, in which the original form of the pebble was not modified. They seem, like the axes mentioned above, to be not a type, but a result of unskilled labor producing the easiest made form of tool. In all specimens the groove is less than half as deep across the inner side as across the outer side. The fourth full groove specimen is well made and finely, finished. It appears to have been originally a three-quarter groove specimen in which part of the outer side of the poll was broken off. The groove then had been deepened at the inner side to give sufficient hold, the, inner side then becoming the outer side.

There are three other hammers which show modification from an original ordinary three-quarter groove type. These have a double groove, the second groove resulting in each instance from an effort to re-utilize the axe after wear or breakage had made it impossible to continue using the old groove.

In four hammers the edges of the grooves are raised above the surfaces of either the faces or the polls or both. Here again the variation in form is a result merely of an effort to continue the hammer in use after breakage or excessive wear. The raised groove edges have resulted from continued re-sharpening of the blade or re-shaping of the poll by packing. As the poll or face surfaces were pecked away repeatedly, the edges of the grooves were not worked down and consequently finally came to stand up well above the surfaces of the hammers.

It seems worthwhile to record these instances because of their indication of the reluctance to discard an axe, once it had received its original shaping. Economy of materials and labor dictated attempts to repair every broken tool for as long a period as it was mechanically possible.

PICKS. Two stone picks were found in the excavation, (Fig. 11, f and g). Both have the three-quarter groove. One of the specimens, (Fig. 11, g), is identical with specimens from the salt mine at Camp Verde figured by Earl Morris.

MAUL. The single example of a tool which was clearly designed expressly to be a maul was shaped from a flat basalt pebble. It was oval in form, 5-3/4 inches long, 3-3/8 inches wide, and about an inch thick, weighing 1-1/4 pounds. The only shaping that had been carried out consisted of the notching of two sides of the pebble to accommodate the haft. The ends of the pebble were blunted by use in hammering.

PAINT MORTARS, ETC.

Twenty-one small mortars, used for grinding paint stone, were found. They varied in diameter from 1-1/4 to 3-1/4 inches The usual type was circular and an inch or more in height with a shallow depression, but there were variations of form. Most important of the variations were a zoomorphic form, and two specimens which conform to a type which seems to be of persistent, but not common, occurrence at sites in the Upper Verde region. The zoomorphic form was found beneath debris on the floor of one of the early rooms in Group III; Room 9. All of the mortars were made of black or red pumice or, perhaps more properly a very fine scoriaceous basalt or ryolite.

Also made of the fine scoriaceous material were three large dishes and three miniature metates.

ARROWSHAFT REDUCERS AND STRAIGHTENERS

Four sandstone arrowshaft reducers and twenty-six representative basalt arrowshaft straighteners were found in the excavation. No double groove straighteners and no straighteners of the hole type came to light. The straighteners conform to no general type, their outlines following the form of the original pebble or the broken mano from which they were fashioned. One arrowshaft reducer was combined with a sandstone "pottery anvil", the groove occurring on the top of the handle of the implement. No doubt the use of these tools was not confined to the working of arrowshafts but applied also to the working of bone and to other wooden implements.

SCRAPERS AND KNIVES. Scrapers and knives consisting of thin blades, not hafted, of schist, greenstone, diabase, argillite and fine sandstone were of frequent occurrence. They were of irregular form and greatly varying size. Three had concave blades adapted to the working of cylindrical pieces of wood. In some the edges were nicked at intervals, indicating use as saws.

There was a type of scraper, possibly used as a flashing tool, which had a definite handle in one piece with the blade. These were made of green schist or diabase.

GRINDERS AND "POTTERY ANVILS". In abundant use, at Tuzigoot was a type of small grinding tool, circular in cross-section and either with or without a definitely formed handle. Those with a clearly defined handle portion are similar in form to tools that have elsewhere been referred to as "pottery anvils".

They may be divided into four classes as regards shape. The simplest form is a short cylinder or thick disc, one end of which has been used for grinding. These vary in size from 1-1/2 to 4 inches in diameter. They were generally made of a fine red or yellow sandstone. Another less common form is tapered toward the handle end. Of not very common occurrence is the thick disc type with a groove completely encircling its center. These have been interpreted by some as heads for war-clubs, the groove being for the purpose of hafting, but the Tuzigoot specimens show very clearly, that one surface has been used for grinding and not for pounding. Specimens were made of basalt, of dolomite, and of fine red sandstone.

The most common form of small grinder is that of the "pottery anvil". These varied at Tuzigoot from 2-1/4 to 4 inches in diameter and from 2 to 3 inches in height. The bottom surfaces of all but nine have been worn smooth by grinding. Two-thirds, or twenty-two, of the specimens have very flat bottoms and would not have been adapted to fit the curves of even the largest ollas found at Tuzigoot in the pottery finishing process. The other third have more or less rounded bottoms, but tend toward flatness, and all but five of eleven show smoothness and wear from grinding use in the centers of the bottoms. The five which show no wear and have definitely rounded bottoms, could have been used exclusively as pottery anvils. If the others were used as pottery anvils, they were also in use as grinders. The majority were made of fine sandstone and a very hard dolomite, but a few were made of both scoriaceous and non-scoriaceous basalt.

PESTLES. Sixteen stone implements which are apparently pestles, although none were found in conjunction with a mortar, were found during excavation. All were made of basalt.

POUNDERS. Closely applied to the pestles are pounding stones, perhaps pemmican pounders as Kidder has called similar tools. Cylindrical or slightly tapering in form, they were made mainly of basalt, but also of sandstone and dolomite. All show definite evidence of use for pounding at the ends. One heavy dolomite pounder, weighed five pounds and had depressions for fingerholds on either side.

HAMMERSTONES. More or less spherical pieces of chert, dolomite, and diorite were used as hammerstones. They were not hafted. They were from 2 to 5 inches in diameter and weighed anywhere from 6 ounces to over a pound. Eighteen were found in the excavation.

RUBBING STONES. Oval sandstone tools with one surface smoothed by grinding, usually about 4 inches long, were numerous. They do not seem to have been used as manos. They may have been used in smoothing plaster or for similar purposes.

WHETSTONES. Three pieces of schist about 1/2 inch thick and 2 inches wide, broken at the ends, with warn shallow depressions on their major surfaces were found. They might have been used for sharpening of the softer stone blades or for grinding down beads or other small objects. They are very similar to schist whetstones found in ruins in the vicinity of Prescott, Arizona.

GOUGE AND CHISEL. A small piece of greenstone, about 2-1/2 inches lang, with a sharp curved edge was found. A similar tool, but without the hollowing of the blade end, was 3 inches long and 3/4 inch wide.

POLISHING PEBBLES. Fifty-four river pebbles varying in shape, size and color, some as large as 2 inches in diameter, were found. They had undoubtedly been used in polishing pottery.

OTHER OBJECTS OF STONE

Toy tools, ceremonial objects of known and unknown use, and naturally occurring, but exceptionally formed stone objects were found in the excavation.

MINIATURE AXES. Two tiny axes of green schist, had probably been made for toys. They were very crudely made, but the edges were fairly sharp and full grooves for hafting were clearly defined.

PLUMMET SHAPED OBJECT. A piece of very hard hematite, dark red in color, had been neatly shaped to the form of a tapering cylinder, at the larger end of which had been made a shallow groove. It was smoothed and highly polished.

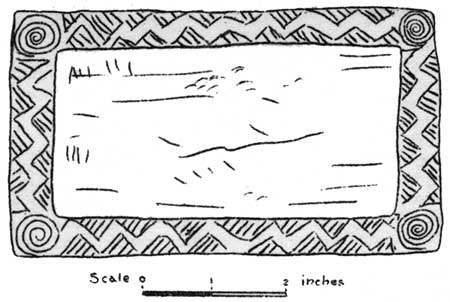

PALETTES. Two palettes, made of mica schist, were found, one of which is illustrated in Fig. 12. The one not illustrated was similar in form, but not so well made and without the geometrical incised designs about the border.

|

| Fig. 12. Paint palette of mica schist. |

PIPE OR CLOUD-BLOWER. The sole example of a cigar-holder type pipe found in the excavation is tubular and slightly cone shaped.

PAINTED PEBBLE. A somewhat cylindrically shaped pebble, 3 inches long, had been flattened and smoothed at one end. Around the large end, just above the flat surface, had been painted a blue stripe. The rest of the pebble, except for the flat surface, had been painted red. Its use is not known.

STONE BALLS. The balls of stone, ranging from 7/8 to 2-1/2 inches in diameter, had been carefully shaped from sandstone, pumice, and colomite.

PHALLIC SYMBOLS. Several fragments of cylindrical pieces of sandstone and scoriaceous basalt, slightly tapering and rounded at one end were found. These might have been made to represent phallic symbols.

QUARTZ CRYSTALS. Thirteen quartz crystals, ranging in length from 1/2 inch to 4 inches, were found. Three were found with human burials and the exceptionally large, 4 inch one, was found with the burial of a red-tailed hawk in the wall of a room.

FOSSILS. Two brachiopods and two fossil corals, derived from the Devonian Redwall limestone in the vicinity were found in the refuse surrounding the pueblo.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Last Modified: Monday, May 19 2008 10:00:00 am PDT |