|

Field Division of Education Outline of the Geology and Paleontology of Scotts Bluff National Monument and the Adjacent Region |

|

HISTORICAL GEOLOGY AND PALEONTOLOGY (continued)

CENOZOIC

(continued)

Miocene

At the close of the Oligocene tho Rocky Mountains and Black Hills were slightly uplifted, this time without folding. The rejuvenated streams again began to deposit great quantities of sandstone and clays over the Great Plains, and there appears to have been a recurrence of conditions similar to those during the Upper Oligocene. This series of sediments represent the Miocene epoch and has been divided by various workers into several distinct time intervals. Due to the more or less lenticular nature of the Miocene deposits they are not easily traced from one region to another so that the various divisions have received different names in different areas. (See generalized section).

The Miocene beds occurring in Scotts Bluff region have been called by Darton the Gering Formation below, and the Arikaree Formation above. Both these formations are exposed in the nearly vertical face of Scotts Bluff, the Gering having a thickness of about 60 feet and overlying the Brule clays, while the Arikaree has a thickness of 220 foot, capping the bluff. Although the Gering formation is rather sharply distinct from the Arikaree in this region studies made over a broader area seem to show that much of the material comprising the Gering is little more than non-continuous river sandstones and conglomerates, contemporaneous in origin with the lower Arikaree formation.

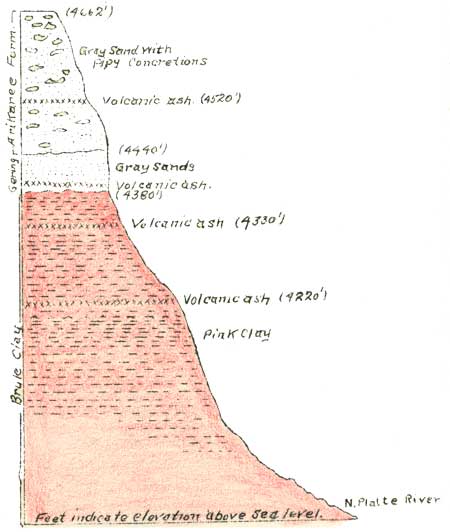

SECTION OF THE NORTH FACE OF SCOTTS BLUFF (From Darton)

The Arikaree formation consists (Darton, 1903, p. 25) mainly of fine sand containing characteristic layers of hard, fine grained, dark-gray concretions, often consisting of aggregations of long, irregular, cylindrical masses. These are commonly called 'pipy concretions" and vary in thickness from a few inches to several feet. Owing to the presence of these, the formation is very resistant and generally gives rise to ridges of considerable prominence.

Among the interesting structures of the Arikaree formation, few have given rise to more speculation concerning their origin than the so called "Devil's corkscrews." These consist of usually upright, tapering, spirals, twisting to the right or left indiscriminately. The spirals sometimes enclose a cylindrical body known as the axis. The spiral may end abruptly below, or may have one or two obliquely ascending bodies placed much as the rhizomes of certain plants. The size varies considerable, the height of the "corkscrew" portion often exceeding the height of a man. (Illus. O'Harra, 1920, p. 47 and figs. 13 and 15).

"Devil's Corkscrews' or Daemonelix, as they are technically called, occur in the Upper Arikaree beds and in some of the overlying formations. They are not distributed throughout the formations but occur at certain localities. Some of the largest and best developed forms occur in Sioux County, Nebraska. The origin of these structures is still the subject of much debate. Barbour, among others, considers them to represent some kind of plant life, either in the form of algae growths or higher plants in which all has decayed away except the cortical layer. Professor Peterson seems to offer a well founded explanation in that at least some of them may have been the burrows of fossorial rodents. Numerous cases have been observed whore fossil remains of burrowing rodents have been found within the corkscrews."

According to Stirton (Stirton, R. A. Unpub. Manuscript U. C.), who has been working on these rodents; no rodent is known which makes a burrow as symetrically and vertically spiralled as some of the specimens of Daemonelix, and it may have been that rodents lived in some of the structures and yet were not responsible for their formation.

There are several well marked faunal zones in the Miocene deposits, each zone being characterized by a rather distinct faunal assemblage. The Lower and Middle Miocene zones are pretty well established, and the faunas are well known. The faunas from the Upper Miocene, Lower Pliocene, and Middle Pliocene are still in need of much revision. The exact occurrence of many of the forms listed from these horizons is doubtful.

One of the most interesting of the Miocene faunas is that from the Agate Springs fossil quarry in Sioux County, Nebraska. (Desc. of Quarry and Fossil Remains from Matthew, W. D., 1923, p. 368) This quarry was discovered by James H. Cook in 1877 and is one of the greatest fossil quarries in America. The bones are in a layer from six to twenty inches. thick, packed closely together. The bones are seldom articulated, but most of the bones of a single skeleton lie near together. The quarry is in the Lower Harrison Formation of Early Miocene age.

Matthew attributes the great accumulation of bones here to an eddy in the old river channel. A pool probably formed at this eddy with quicksand at its bottom and many animals that came to drink at the pool in dry seasons would be trapped and buried in the sand. The covering of sand would protect the bones from decay and prevent them from being rolled and waterworn. However, the shifting sand disarticulated and displaced the bones, but would leave the skeletons complete and undamaged.

The bones from this quarry almost wholly belong to three species, the dwarf pair-horned rhinoceros, Diceratherium cookii the calicothere, or clawed ungulate, Moropus elatus; and the entelodont, or giant pig, Dinohyus hollandi.

The rhinoceros is by far the most abundant. A block, five and one-half by eight feet, taken from this quarry in 1920, and now on exhibition in the American Museum, contains twenty-two skulls, an uncounted number of skeleton bones, all of the little rhinoceros. This form had a pair of horns placed side by side on the nose instead of the single horn of the Indian rhinoceros, or the "tandem" arrangement of the horns seen on the two African rhinoceroses. This species was a little larger than a pig with somewhat the same proportions of body but very different head. The horns were probably not long and pointed but were stout, blunt nubs.

Moropus belongs to the Calicotheroidea, an extinct family of mammals of the order Porissodactyla and about equally related to the horse, the rhinoceros, the tapir, and the titanothere. The neck and general shape of the head remind one of the horse; the short arched back, sloping hips, and the rudimentary tail suggest the tapir. The limbs and feet resemble the proportions and construction of the modern rhinoceroses, except that the fore-limbs are longer. The grinding teeth are most like those of the extinct titanothere, while the front teeth are those of a ruminant. The toes are the most remarkable of this old beast for they are tipped with claws instead of hoofs. This feature, in an animal, that certainly is one of the ungulates, as shown by every other character of its skeleton, is unique and difficult to explain. Calicatheres are scarce among the fossils of Europe and Asia, and very rare in North America except in this quarry. A number of incomplete skeletons were obtained by the Carnegie Museum, and seventeen complete skeletons by the American Museum.

Dinohyus is the largest of the entelodonts. These extinct animals are commonly called giant pigs, although they are not very pig-like in appearance and were not related to the pigs any more closely than the ruminants. They were tall, but compactly proportioned, with two toed feet like a bison's, very large heads with long muzzles and large powerful tusks. The tusks and all the front teeth are much more like wolves, or other large carnivores, than like those of any living herbivores, while the back teeth are of omnivorous type. These beasts were probably omnivorous but well equipped to pursue and attack animal prey.

Another quarry two or three miles from the Agate Quarry and of the same age has yielded great numbers of skeletons of the gazelle-camel, Stenomylus, a small slender creature of the size and proportions of the vicuna. No other animals are associated with it in this quarry. Matthew states that there are good reasons for believing that the Stenomylus quarry was the bedding ground of this extinct animal. Many of the skeletons are completely articulated, suggesting an entirely different means of preservation than that in the Agate Springs Quarry.

The camels originated in North America and it is here that the earliest and most primitive forms are found. This group of animals, so foreign to North America at present, had nearly the whole of its development on this continent, and did not migrate to other countries before late Miocene or Pliocene time. The whole family, however, disappeared from North America in the Latter Pleistocene or at the time of the great Ice Age. The Miocene forms, Procamelus, has long been known and is believed to have been the ancestor of the camels and llamas of today. In general it may be said that the Miocene forms became increasingly more cameloid became larger, the side toes disappeared, the metarsal bone became more fully united, and rugusites of the hoof bones indicate the presence of a small foot pad. (See check list for more complete list of animals known from this epoch).

|

|

|

|

|

|

Last Modified: Tuesday, Feb 21 2006 10:00:00 am PDT |