|

Field Division of Education Indian Tribes of Sequoia National Park Region |

|

Museum Exposition of California Indian Life

In addition to the references to illustrations given in this paper, the Museum of Anthropology of the University of California has a large number of photographs from the tribes concerned which furnish ample data on most topics.

A museum representation of Indians at Sequoia park faces several complicating factors, but has, at the same time, the opportunity to tell a story of unusual interest. If only the Western Mono and Tubatulabal, who are natives to the park, were represented, we should be able to expound a more or less typical Californian but in general rather backward people and we should probably have to be content with a limited number and variety of museum specimens. If, however, the tribes to the east and west are given consideration, we have the opportunity to elucidate facts of the utmost importance and interest.

The Sierra Nevada range forms a sharp division between two native American cultural and geographical provinces. To the east lies the arid Great Basin, harboring the primitive Shoshonean-speaking tribes, who in their struggle, to live in an extremely inhospitable environment, were equipped with only the moat primitive cultural devices, and who, by virtue of their backwardness, are closer than almost any other tribes in America to the first Indians of 20,000 or 25,000 years ago. Specific traits, of course, such as the bow, dog, metate, rabbit skin blanket, and basketry are advanced, but in general their culture is impoverished as compared with any other American Indians. To the west of the Sierra Nevada lies the California province, affording a greater natural abundance of food and supporting cultures which, though primitive as compared with the agricultural tribes of the Southwest, or salmon fishing peoples of the Northwest Coast, had achieved their own special solutions of the problem of living, and had built up something of a distinctive social and religious culture. The Owens Valley Paiute largely typify the Great Basin tribes; the Yokuts possess most of the distinctive traits of the California tribes. The Western Mono and Tubatulabal are in large measure intermediate in development, leaning somewhat toward California. A museum exposition of these cultural provinces, therefore, should bring out the following facts:

First, the Sierra Nevada mountains constitute a major barrier between the two geographical and cultural provinces. In order to indicate this forcibly, a map including the full extent of the Great Basin into Utah, and of the whole of California should be used. On this would be entered the major cultural and geographical areas. Attention should also be called to the relief model constructed for Sequoia Park, for it indicates the magnitude of the crest of the Sierra as a geographical and cultural barrier.

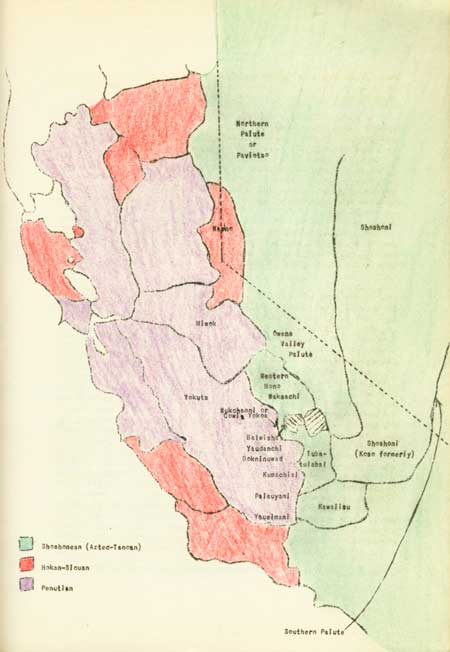

Second, a map should show the distribution of tribes in the region, indicating also the major language groups. This would bring out the fact that the Sierras constitute, in large measure, a boundary between the Shoshonean-speaking Great Basin peoples and the varied linguistic groups of the California province. Such a map would be of local interest and certainly far more important than a general map of North American Linguistic families. It would show that to the east of the Sierra lie the Shoshonean speaking Northern Paiute (Paviotso), Shoshoni, Southern Paiute, and Chemehuevi, while the Western Mono, Tubatulabal and Kawaiisu, also Shoshonean-speaking, are in the mountains; and it would show that California proper is occupied by several stocks. One of the most important of these is the Penutian-Lutuamian, which includes the centrally located Yokuts, Salinan, Miwok, Maidu and Wintun. Another is the Hokan-Siouan, which includes the Costonoan, Shastan, Chumash and Pomo. (See Kroeber, 1925, pl. 1 for further details.)

Third, the cultural differences between the peoples on the opposite sides of the Sierras should be brought out. Exposition of these differences would first emphasize the fact that the natural basis of life in the two provinces is different. In California wild foods were relatively abundant and sufficed to support a large population, in the absence of agriculture. No one food, however, formed the hub of economic activities as did the bison in the Plains, the salmon on the Northwest Coast, maize in the Southwest. Instead, everything was utilized, all kinds of game being taken in a variety of ways, and all edible seeds being gathered and roots dug. The relatively great reliance upon roots has merited the California Indians generally the popular but entirely meaningless name, "Diggers". If any one thing served as a specialized food and required specialized techniques, it was the acorn, which became the center of a very interesting complex. In contrast to the relative abundance of food in California, the Great Basin afforded so little that life was a continual struggle. As in California, everything possible was utilized, but the pine nut, growing on the desert ranges, supplanted the acorn as the staple food and required its own series of techniques for gathering, storing, and preparation. These and other differences between the two provinces will be explained below. In a museum exposition of these points, there should be, so far as possible, a comparative series of illustrations or actual objects of the two cultures.

In this connection, a map should show the cultural sub-areas of California (see Kroeber, 1925, figs. 73 and 74, pp. 903, 916.), making it plain that the Yokuts-Western Mono culture belongs with the south central area, which is set off from the Northwest salmon culture (which is allied with the Northwest Coast), and the southern California sub-area which is somewhat distinctive, somewhat allied with the Southwest. The museum should also explain the interesting fact that as California is extremely varied topographically and in natural resources, so its native inhabitants had more than ordinarily varied arts and industries, quite different modes of life being found within a relatively small region.

A fourth point that should be brought out is that native trade was carried on across the Sierra Nevada, definite trails being used and a considerable variety of objects being transported. Trails, campsites, etc., could be designated on maps. Such information as is available on this subject will be indicated below.

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

|

|

|

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Jul 10 2004 10:00:00 am PDT |