|

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Fauna of the National Parks of the United States No. 4 Ecology of the Coyote in the Yellowstone |

|

CHAPTER I:

INTRODUCTION

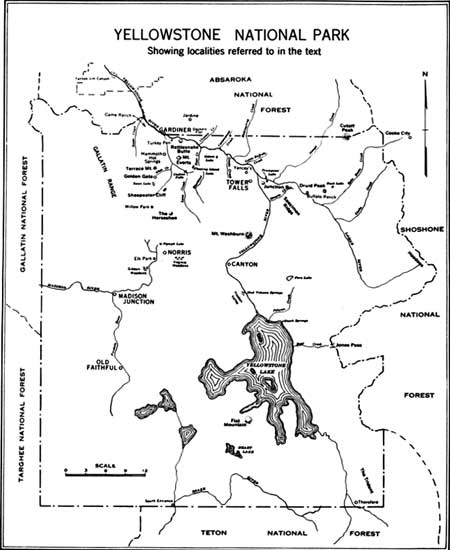

(click on map for an enlargement in a new

window)

LOCATION AND GENERAL CHARACTER OF AREA

YELLOWSTONE National Park lies in northwestern Wyoming and takes in narrow strips of Montana and Idaho. It embraces about 3,500 square miles of mountainous and plateau country, volcanic in origin. Yellowstone Lake, near the center of the park, is surrounded by broken and rolling country sometimes called the central plateau, having an average altitude of 8,000 feet above sea level. This central plateau is bordered by mountain ranges reaching an altitude of about 10,000 feet. The north side of the park is lower, varying from about 5,300 feet near Gardiner to 6,500 feet at the Buffalo Ranch on the Lamar River. This area, along the Yellowstone and Lamar Rivers, receives less snowfall than the more elevated interior and constitutes the main winter big game range in the park. A large part of the park is covered with lodgepole pine, but Douglas fir and spruce are common species, and whitebark pine is found at high altitudes. Open grassland is common on the high slopes and throughout the low northern area, interspersed with sagebrush in the latter locality. Small meadows occur abundantly all over the park. The Upper Sonoran Zone reaches into the park at Gardiner. Most of the park is in the Canadian Zone and the Hudsonian and Arctic-Alpine Zones are also represented. The general character of the flora and fauna of Yellowstone National Park can be secured from Bailey (1930) and Skinner (1927).

North of Yellowstone National Park lies the Absaroka National Forest and the long open valley of the Yellowstone River; to the east is the rough wilderness of the Shoshone National Forest; to the south is the Teton National Forest and the Grand Teton National Park embracing the beautiful wild Jackson Hole country; to the west lies the Gallatin and Targhee National Forests. Yellowstone National Park is surrounded by a number of wilderness areas, a fact which is important in the preservation of rare carnivores within its boundaries.

EARLY WILDLIFE CONDITIONS IN YELLOWSTONE

PLANS, policies, attitudes, scientific interpretations, and hopes in regard to the wildlife in an area are contingent on the relationships between its present and its primitive status. If present conditions differ widely from the primitive, then we may have an unnatural association of animals; the animals may be existing by recently acquired habits, they may be subjected to new predators, or to the old predators in areas of strange physiographic and floral features to which they are not adjusted. If present conditions are in the main similar to the primitive then the relationships are perhaps deeper, more stable, more significant, and represent the results of a long process of adjustment. To arrive at the primitive picture I have perused some of the early literature and compared the experiences of the early travelers with my own experiences in the mountains. Since my conclusions are contrary to those generally accepted it has seemed desirable to give briefly some support for them.

It is frequently said (Rush (1932), Skinner (1927), and others) that in the early days game was scarce in the mountains; that it is much more abundant there now than it was originally; that game migrated to the mountains about 1880; and that game was more abundant on the plains than in the mountains. The last statement seems true; the preceding ones lack evidence for their support, because it is probable that the mountain animals were the only ones to escape destruction; and the first two conclusions appear untenable in the light of evidence found in early reports and journals.

In analyzing the statements made by early explorers some points must be kept in mind. First, negative evidence must yield to positive evidence because failure to report game does not disprove its abundance. Difficulty in finding game where it is known to be abundant is a common experience. Acting Superintendent F. A. Boutelle in a supplement to the 1889 Yellowstone Annual Report makes the statement: "Visitors are sometimes a little incredulous as to the great number of large game animals in the park and complain that they have seen nothing." In more recent years I heard a superintendent make a similar remark in regard to the abundance of elk in Yellowstone. While studying elk in Teton National Forest south of Yellowstone in 1928 where hundreds of elk were summering, there were periods, especially in late summer, when the elk were more in the woods and we had difficulty finding the animals. In 1938 I heard an old-timer, familiar with all details of the Jackson Hole elk country, say that he had been out on the elk summer range for more than a week to photograph them and had hardly found an elk. It is not at all surprising to me to read of early hunting parties failing to shoot game in good mountain game country. Some other factors operating in varying degrees to give the impression that game was originally scarce in the mountains are: (1) game in summer was largely at high elevations away from traveled routes; (2) game was often much hunted along the routes and may have been locally scarce; (3) large parties were noisy, resulting in game being scared away; (4) large parties needed a big supply of game and at regular intervals, so it was not unexpected that they should run out of food; (5) although game was no doubt more plentiful in the plains country than in the mountains the contrast was accentuated by wider visibility and easier hunting on the plains; (6) as in present-day journals, game was often referred to only casually, so all game was not necessarily listed; and (7) some habitats in the mountains, such as the dense lodgepole pine, are poor in game today, and the naturalist of the 1872 Hayden party traveled through Yellowstone largely in this habitat and not through the best summer game country. So much for explaining the impression sometimes obtained that game was scarce in the mountains.

One of the most fascinating books on early western travel is the Journal of a Trapper by Osborne Russell. It covers several trips made by the author into Yellowstone between 1834 and 1843. The diary is exceptionally well written and the author was apparently a careful and truthful observer. In the following, the localities given in parentheses are mine, but quotations and comments are taken from Russell.

July 2,1835 (Jackson Hole). "This valley, like all other parts of the country, abounded with game."

July 28, 1836 (Jackson Hole). "Game is plentiful and the river and lake abound with fish."

August 19, 1836 (Outlet to Yellowstone Lake). "This valley was interspersed with scattered groves of tall pines, forming shady retreats for the numerous elk and deer during the heat of the day." Seven trappers killed a cow, probably in Hayden Valley, and a wolf was heard howling.

August 7, 1837. On the divide between Stinking Water and Yellowstone Russell's party fell in with a large band of bighorn.

August 12, 1837. The party crossed the divide (Jones Pass?) to the waters of the Yellowstone Lake "where we found the whole country swarming with elk."

July 10, 1839 (Old Faithful Area). "Vast numbers of black-tailed deer are found in the vicinity of these springs . . ."

July 28, 1839 (Yellowstone Lake). Russell speaks of the Indians shooting at a large band of elk. In late August (near Heart Lake) they fell in with a large band of elk and killed two cows.

In The Discovery of Yellowstone Park—1870, by N. P. Langford, the following observations were noted: September 6, 1870 (southeast corner of Yellowstone Lake): "We have today seen an abundance of the tracks of elk and bears, and occasionally the track of a mountain lion." On September 7, 1870, near the mouth of the Upper Yellowstone River, the party followed by mistake a fresh trail made by a band of elk.

F. V. Hayden (1872) gives some interesting light on abundance of game in Yellowstone and the difficulty of finding it, even when abundant. He writes of Yellowstone: "The finest of mountain water, fish in the greatest abundance, with a good supply of game of all kinds . . . On the evening of August 9 we camped at the head of the main bay (Yellowstone Lake) west of Flat Mountain. Our hunters returned after diligent search for two and a half days with only a black-tail deer which, though poor, was the most important addition to our larder. It seems that during the months of August and September the elk and deer resort to the summits of the mountains to escape the swarms of flies in the lowlands about the lake. Tracks of game could be seen everywhere, but none of the animals themselves was to be found."

In the Sixth Annual Report of the United States Geological Survey of the Territories, by F. V. Hayden (1873), the following reference is made to game early in September 1872, south of Heart Lake in the Yellowstone Region: "This is mostly fine grazing ground and the numerous game trails give evidence that it is frequented by deer and elk; indeed, we found two herds of elk of about 20 each among the groves on the top of the ridge."

The following references to game occur in the Report Upon the Reconnaissance of Northwestern Wyoming, Including Yellowstone National Park, Made in Summer of 1873, by William A. Jones: August 2. On the divide between North Fork of Shoshone and the Yellowstone basin fresh tracks of mountain sheep were reported as exceedingly numerous. September 2, 1873 (10 miles up Upper Yellowstone River): "All through this basin game tracks have been very abundant, but our party from its size makes a good deal of noise, which will account for the fact that we did not see a great deal. A magnificent elk crossed the valley in advance of us, and in plain sight today." On September 3, 1873, three elk were seen and shot at Two Ocean Pass.

The following notes are taken from the geological report made by Theo. B. Comstock, included in the Jones report: On August 6, near Pelican Meadows, the "doleful howl of a large wolf which was slowly approaching along the trail" was heard. The camp was on a "well-worn game trail. . . This locality seems to be a favorite resort of many animals. Our train approached it by following a prominent game trail, at least a dozen of which, extending for miles into the forest, meet at this point. Upon my first visit to this place, the day before the passage of the train, fresh tracks and other unmistakable signs of their presence were visible. Today I started numbers of elk while passing through the fallen timber." On August 12, 1873, a badger was seen at Canyon and a porcupine was killed in Hayden Valley. The following is written about a trip from Pelican Creek to Mirror Plateau on August 13, 1873: "Plentiful tracks of game were noticed, but we saw very little until near the summit, when we met a large drove of elk and some deer." Item for August 19, between Junction Butte and Hellroaring: "On the way we met with several large droves of antelopes feeding upon fine pasturage here afforded with much security, owing to the irregular topography which enables them to seek immediate shelter upon the approach of danger. At the time of our visit the great antelope country along the left bank of the East Fork (Lamar River) was remarkably free from their presence, which may doubtless be explained by the recent passage of several parties of miners."

In "Report of a Reconnaissance From Carrol, Montana Territory, on the Upper Missouri to the Yellowstone National Park and Return Made in the Summer of 1875," by William Ludlow (1876), the following statement indicates that many elk wintered in Yellowstone: "Hunters have for years devoted themselves to the slaughter of the game, until within the limits of the park it is hardly to be found. I was credibly informed by people on the spot, and personnally cognizant of the facts, that during the winter of 1874 and 1875, at which season the heavy snows render the elk an easy prey, no less than from 1,500 to 2,000 of these, the largest and finest game animals in the country, were thus destroyed within a radius of fifteen miles of the Mammoth Springs." This slaughter is mentioned in Norris's report of 1880.

The following notes are taken from the zoological report prepared by George Bird Grinnell, published in the Ludlow report. Of mountain lions he states: "Although not a common species, a few of these animals are killed in the mountains every winter." One was seen near Alum Creek. Lynx were reported abundant in the mountains and sometimes killed in the park. Apparently, coyotes were present in some numbers in the mountains, for the following statement on their abundance is made in writing of the coyote: "This species is abundant between Carroll and Fort Ellis, being, I think, much more common on the prairie than in the mountains." The coyote was apparently very plentiful on the prairie where it was possible to see it much more easily than in the mountains. The above comparison suggests that the coyotes were present in some numbers in Yellowstone. Many wolverine tracks were reported in the park. The grizzly was reported as numerous in the park and black bears were scarce. Concerning elk, the following statement is made: "They were seen in considerable numbers along the Missouri River, among the Bridger Mountains, and in the Yellowstone Park." The bighorn and "the so-called mountain buffalo," were reported abundant in the park.

The following statements concerning early game conditions are taken from a typewritten copy of "A report made by Lt. G. C. Doane on an Exploration Trip from Fort Ellis Through Yellowstone Park and Jackson Hole to Fort Hall, Between October 11, 1876, to January 4, 1877." Observations made in the summer of 1874 up Tower Creek are mentioned, which show that many elk had wintered in Yellowstone. He writes about a side trip made in 1874 as follows: "Late in the afternoon we reached the summit of the mountain toward Mammoth Springs, coming out in an open space where there were thousands of elk horns. There are many such places in the park where these animals have gone for centuries to drop their horns in early winter." On October 22, 1876, they were camped at Crystal Spring Creek near Canyon. He writes: "Hunted in vicinity of camp but found nothing." Later in Hayden Valley he reports ". . . saw that I had ridden close up to a herd of at least 2,000 elk. They had been lying in the snow and had all sprung up together, frightening my horse. In a minute the great herd was out of sight, crashing through the forest." A deer was killed 6 miles from Mud Volcano Springs near the mouth of the Yellowstone River. October 24, 1876, Yellowstone Lake: "In the morning I shot and wounded a large wolverine but did not stop him. . . ." October 26, 1876, Yellowstone Lake: "Killed a deer and two geese. . . . Mountain lions in chorus beyond the river, and a pack of wolves howling far down the lake shore." October 29, 1876, 1 mile from Heart Lake: "Driving a large herd of elk resting there we went into camp." November 18, 1876, on Snake River south of Heart Lake: "We have had but little depth of snow and this while favorable in one sense has been detrimental in another, as it has allowed the game to run high on the mountains where we had not time to go." South of Heart Lake a mountain lion had visited camp during the night.

In his annual report on Yellowstone Park for 1877, Supt. P. W. Norris gives a discussion of wildlife conditions in Yellowstone which corroborates the foregoing statements. He says: "Hence in no other portion of the west or of the world was there such an abundance of elk, moose, deer, mountain sheep, and other beautiful animals, fish and fowl, nor as ignorant, or as fearless of and easily slaughtered by man as in this secluded and unknown park but seven years ago . . . . From the unquestioned fact that over 2,000 hides of the huge Rocky Mountain elk, nearly as many each of the bighorn. deer, and antelope, and scores if not hundreds of moose and bison were taken out of the park in spring of 1875, probably 7,000, or an annual average of 1,000 of them, and hundreds if not thousands of each of these other animals have been thus killed since its discovery in 1870. . . . As comparatively few of them were slain for food, but mostly for their pelts and tongues, often run down on snowshoes and tomahawked when their carcasses were least valuable, and merely strychnine-poisoned for wolf or wolverine bait, the amount of most wholesome, nutritious, and delicious food thus wantonly destroyed is simply incalculable." The fact that these animals were taken out of the park in the spring and that some were run down on snowshoes indicates that the animals must have been wintering in the park.

The following quotations are taken from Superintendent Norris' Yellowstone report made for the year 1880. Referring to Soda Butte Creek he writes: "A branch of the East Fork (Lamar) of the Yellowstone and a favorite winter haunt of elk and bison . . . Elk, deer, and other game being driven by storms into the sheltered glens and valley, we were enabled to secure an abundant winter's supply of fresh meat, and also fine hides of the bear, wolf, and wolverine . . . I would add that there are now in the park abundance of bison, moose, elk, deer, antelope, and bighorn sheep besides fine summer pasturage there are winter haunts for these animals where with little care or expense other than protection from wanton slaughter, they would rapidly multiply." He mentions the presence of countless brush and stick fences of various ages created by the Indians for driveways in hunting game. Of elk he writes that in no place were they more abundant than in Yellowstone in 1870, and that a big slaughter of them occurred between 1870 and 1877. They were found at high elevations in summer and in sheltered valleys of the park during winter. Bighorns were recorded abundant throughout the park, remaining there the year round. The cougar was said to be exceedingly numerous in 1870 when Norris first explored the park, but already rare in 1880. Wolves and coyotes are reported to have once been exceedingly numerous in all portions of the park, but that the value of their hides and their easy slaughter with strychnine-poisoned carcasses of animals had nearly exterminated them by 1880. Foxes, shunks, and badgers, are said to have been numerous in 1881.

Edward Pierrepont in "Fifth Avenue to Alaska" wrote that bighorn were abundant in the Hoodoo Mountain area in 1883. Game Keeper Harry Yount in 1881 reported sheep wintering in large numbers at Norris Mountain.

The paleontologist E. D. Cope (1885) made the following statement concerning early conditions in Yellowstone: "Bison, elk, moose, deer, etc., are far less abundant than when the park was first created. The bison have been, I am informed, reduced to a herd of about 60 individuals, and the elk have been decimated . . . Some persons state . . . that the game leaves the park in winter. This I ascertained is not true, for there are numerous well-protected localities where the game winters safely."

M. S. Garretson, secretary of the American Bison Society, in a letter to Fred Packard, written February 2,1939, gives a good historical description of early game conditions in Yellowstone Park and the plains country to the east. Mr. Garretson writes as follows: "My first acquaintance with the park was in the early eighties and I have been interested in it ever since. The knowledge gained then and since that time confirms my belief that prior to the advent of the white man the Yellowstone region was well stocked with game as were also the foothills and the open plains country. On the east and from the railroad on the south the game was being rapidly slaughtered by the advancing settlers and ranchers; at the same time on the western edge of the open country and in the foothills there were numerous hide hunters, market hunters, miners, and so-called sportsmen who worked eastward. After the game had been destroyed in the open country the hide hunters and market hunters continued their activities in the more difficult mountainous regions.

"The slaughter was prodigious even after the boundaries of the Yellowstone Park had been established. Thousands of elk and many bighorn sheep were slaughtered annually within the park for their hides and meat until a Federal law had been enacted for their protection, so it is quite apparent that instead of being driven into the park the original inhabitants were given the same treatment as was accorded to those in the open country and were slaughtered to near extinction, so there is good reason to believe that all the elk in the Yellowstone Park today have descended from the original inhabitants."

COMPARISON OF THE PRIMITIVE AND PRESENT WILDLIFE STATUS

IT IS DIFFICULT to reconstruct the primitive wildlife picture in Yellowstone even though a considerable number of early reports on wildlife have come down to us. There has not been opportunity to examine all the literature, but I feel that enough has been covered to make a general comparison of the primitive and present status of some species.

Elk.—It appears that formerly elk were accustomed to summer in Yellowstone Park in as large numbers as today or even larger; the early writings show that many elk wintered in Yellowstone. However, it is likely that more elk moved out of the park than at present, especially during severe winters, thus resulting in a better adjustment between numbers of animals and the condition of the winter range. Yellowstone furnished a good winter range for a number of elk and the ranges outside the park were sometimes grazed bare by buffalo, a circumstance which may have affected elk distribution in this region during early times.

Mule deer.—It is probable that mule deer were formerly more abundant in the park in summer than today. I have seen no reliable information on early winter distribution in the park but since deer are now wintering on typical mule deer broken foothill range where winter conditions are favorable it seems probable that the early winter distribution in the park was much as at present.

Whitetail deer.—This species probably summered in the park in fair numbers in early days, coming into the park from the winter ranges along the Yellowstone River to the north, from Jackson Hole to the south, and perhaps from other surrounding valleys. As late as 1914 a hundred of these deer wintered along a short stretch of the Gardiner River near the north boundary. In the park the whitetail deer winter range was of small extent and was heavily browsed; the winter range of willow bottoms outside the park was usurped by ranchers. The vanishing of a suitable winter habitat for this brush-loving, secretive species was probably the basic cause for its disappearance. Vernon Bailey (1930, p. 69) writes as follows about the disappearance of the whitetail: "To a limited degree they were migratory in habits. Usually a part of those in the park drifted down the river valley in winter below the boundary where they had little protection and were an easy prey to pot hunters. A protected area below the park line could have saved them but this was not provided." In early times the whitetail was common in Jackson Hole, but there, too, they have largely disappeared. The few now remaining are reported from the Snake River Bottoms.

Buffalo.—In the early days buffalo were apparently found the year round in Yellowstone. Most of those living in the park when it was established were killed off by poachers. The propagation of a so-called "tame" herd on the Lamar River, together with the survival of a few of the original population in the Pelican Creek area, has resulted in a population of about 850 animals. The present distribution, because of transplants in Hayden Valley and the Old Faithful areas, is probably similar to the early distribution.

Antelope.—At one time antelope summered in Hayden Valley and the upper reaches of the Gardiner River as well as in the present summer range between Gardiner and Cache Creek. It appears that the summer antelope population is smaller now than formerly. Since the antelope winter range in the park is suitable, it is likely that a few of these animal always have wintered within the present boundaries. Formerly most of the antelope probably wintered in the Yellowstone Valley below Gardiner.

Bighorn.—In early days the bighorn summered in the park more widely and in greater numbers than at present and more of them spent the winter within its boundaries. Bighorns occurred in places where they are now absent.

Moose.—The abundance and distribution of moose have always varied. Their present status is probably similar to that of primitive times.

Cougar.—Formerly common in Yellowstone, cougars are now very rarely reported. They were hunted until they became scarce in the nineties. In 1914, 19 were killed by the use of dogs.

Wolf.—Although once present in good numbers, it is probable that none now remains. In 1912 wolves were reported, but none taken. In the 1914 annual report grey wolves were said to exist in the park, and at later dates some were destroyed. Poisoning was the principal method used to kill hem.

Other mammals.—The coyote has probably always been abundant in the park. Formerly the red fox was very common in the area; now it is relatively rare. Poisoning and trapping operations were undoubtedly the factors in its decimation. Wolverines and bobcats, once common, are now apparently gone; and lynx, which were formerly equally common, are extremely scarce at present.

Probably the present grizzly bear population does not differ widely from the primitive numbers. Black bears are apparently more plentiful now, although the data are rather fragmentary. George Bird Grinnell in 1875 found black bears scarce.

In all likelihood badgers today occupy much the same status as formerly. Fishers, once present, are now absent.

Birds.—Sage hens, at one time present in limited numbers, are now gone. They were probably killed off by hunters. Little brown cranes are not as abundant today as in primitive times, undoubtedly due to a general country-wide reduction in their numbers. Willett and greater yellow-legs, which George Bird Grinnell reported abundant in 1875, are now scarce or absent. This may also be due to a country-wide reduction in their numbers.

Conclusion.—The general pattern of wildlife today is similar to that existing when Yellowstone was first explored. There has been a reduction in some of the ungulates, but the big difference lies in the scarcity or absence of many of the predators. The relationships of the Coyote to the rest of the fauna is today similar to what it was formerly.

PREDATOR CONTROL

IN EXAMINING the annual reports of the superintendents of Yellowstone it has been exceedingly interesting to observe the attitudes concerning predators which have been held in years past. Almost from the beginning a feeling against predators existed. Only occasionally is a voice raised in their defense, and then it speaks apologetically and with deference. This attitude toward predatory animals is easily understood, for one kill or an apparent kill makes a striking impression on the mind. The attention is held by an individual instance rather than by the effect of predation on the entire population. Because in the early days hunting was so wanton as to imperil the existence of game animals, much conservation thought was directed toward their preservation. Efforts were made to overcome every factor which might be considered in any way inimical to the well-being of the game. Hence predator control activities have persisted throughout the country and are constantly broadening in scope so that more and more species fall within this complex. The history of predator control in Yellowstone National Park is typical of that existing in many parts of the country. I have recorded here some of the early attitudes on predation and some of the data on control of predatory mammals in Yellowstone in order that we may better understand the human element that enters into the picture, and particularly in order that we may learn why certain forms have become rare or have disappeared from Yellowstone.

At the time Yellowstone National Park was established in 1872 there was considerable mining activity on the north and east at Cooke City. Miners passing between Gardiner and Cooke City hunted both carnivores and big game animals. There probably were also some market hunters in the area at this time.

Supt. P. W. Norris in his 1877 report on Yellowstone National Park described an orgy of big-game hunting which took place in the park during the late winter of 1874—75, and stated that many of the carcasses were strychnine-poisoned for wolf (timber wolf and coyote) and wolverine. There seems to have been much poisoning of flesh eaters in the park in this early period. In his 1880 annual report Norris stated that he and his party gathered fine hides of bear, wolf, and wolverine at the mouth of Soda Butte Creek. At this time moderate hunting for camp use was permitted in the park. In the report of 1880 the cougar was stated to be exceedingly numerous in 1870 and scarce in 1880, so it is likely that many of them had been killed during this period. Wolves and coyotes were reported abundant in 1870, but scarce in 1880 because of poisoning activities. Hundreds of skunks were killed around Mammoth. Beavers were reported plentiful, but trappers had removed many of them.

Supt. D. W. Wear in his annual report for 1885 wrote of the unfortunate hunting activities which in the past had prevailed, and recommended that there should be no shooting or hunting of any kind allowed within the limits of the park. Moderate hunting by travelers for camp purposes was still being permitted at this time.

By 1887 it appears that practically all forms of wildlife were receiving protection. Supt. Moses Harris in his annual report of 1887 was not greatly concerned over the depredations of predators, as can be seen from the following quotation: "I have heard considerable anxiety expressed by those who profess interest in the park lest the rule which protects equally all animals in the park should work to the detriment of the game proper by causing an undue increase in carnivora. But while it is true that there are some noxious animals that are not worthy of protection, chief among which is the skunk, or polecat, yet I am convinced that at the present time more injury would result to the game from the use of firearms or traps in the park than from the ravages which may be feared from carnivorous animals."

That there was pressure for predator control from some source is also evident from Superintendent Harris's report of 1888. He had sent a scouting party into the park to observe game. They had traveled to Yancey, Specimen Ridge, Hayden Valley, Pelican Valley, and Norris, and had reported many elk, deer, and mountain sheep. Since tracks of only two mountain lions had been noted and few other carnivorous animals were seen, Harris wrote that the fear of those who believed that the game animals might be exterminated by the carnivora might be considered as without present foundation.

In the supplemental report to the annual report of 1889 the new Superintendent, Capt. F. A. Boutelle, recommended control of predators although with no reason except that they were becoming plentiful along with other animals. He wrote: "The carnivora of the park have, in common with other animals, increased until, I believe, something should be done for their extermination. This will be made the subject of a special letter. If the proposition is favorably considered the work should be done by persons under my control." Control of predators had at this time apparently not been resumed. In the 1890 annual report Boutelle again suggests control of carnivores although he reports the game animals increasing. He may have been inaccurate concerning abundance of the game but his reasoning is interesting: "The number of elk in the park is something wonderful . . . In the neighborhood of Soda Butte herds were seen last winter estimated at from 2,000 to 3,000. The whole open country of the park seems stocked to its capacity for feeding. Other varieties of game animals are thought to be increasing rapidly." In the next paragraph he goes on to say that calf crops are too small: "As reported last year the herds of buffalo and elk do not seem to have enough calves. I am more than ever convinced that the bear and puma do a great deal of mischief and ought to be reduced in numbers. While they may be something of a curiosity to visitors to the park, I hardly think them an agreeable surprise. Very few who come here 'have lost any bear'."

In his annual report for 1893 Supt. George S. Anderson reported that beaver were being taken by poachers in all parts of the park, so other fur bearers were no doubt being poached to some extent. In his 1895 report Superintendent Anderson stated that ". . . the park can well spare whatever of other game they (bears) may consume for their sustenance " thus showing a tendency toward a broad point of view on the subject of predation. In Superintendent Anderson's annual report for 1896 coyote control is recommended because the animals were numerous—not because they were injurious. The wording in the following passage from the report indicates that there may have been considerable pressure for control: "The game continues to increase and all varieties, excepting the bison, are found in great numbers. During the spring months the elk are found in their several winter ranges in herds of thousands. Deer wander through the Post, going within a few feet of the buildings and often as near to the men, who are about their work. The usual herds of mountain sheep and antelope have wintered on Mount Evarts and show great increase of numbers. The carnivora have also increased and have proved objects of interest to tourists. In the winter coyotes hereabouts became so numerous that I at last felt obliged to order the destruction of some of them, but I confined this duty to the authorized scout. I find the young of all the ruminants especially numerous and in good condition, so that I expect a large increase for the year."

Supt. S. B. M. Young in his report for 1897 requested that coyotes be controlled. His remarks indicate that there was a faction at that time friendly to the coyote. "The coyotes are numerous and bold. It is estimated that of a herd of 500 antelope that wintered in the valley of the Gardiner and on the slopes of Mount Evarts 75 (15 percent of the herd) were killed by coyotes during the past winter, and many antelope fawns, elk calves, and broods of grouse have been destroyed by them this season. The opinion has been advanced by a few of the friends of the park that if the coyote is exterminated the gopher in time would eradicate the grass from the winter valley ranges. I do not concur in this opinion, and request authority to reduce the number so that they will not hunt in packs."

Supt. James B. Erwin in the annual report for 1898 writes as follows concerning control of coyotes: "Very numerous in certain sections. They do some damage to the young elk, but the young deer and antelope are their particular prey. Efforts are made in winter to keep their number down by poisoning carcasses of dead animals, and to a certain extent it has been successful." Concerning antelope and deer he wrote in the same report: "These (antelope) are yet numerous. The snow drives them from the mountains and high plateaus, their feeding and breeding ground in spring and summer, to the lower altitudes outside of the park, where many are killed (by poachers)." Deer were "numerous, on the increase." Poisoning of coyotes must have been quite successful, for in the diary of one of the scouts, published with the report, eight dead coyotes were found near the target range in 1 day (December 5).

In the annual report for 1899 the statement is made that the coyotes "undoubtedly kill many antelope, as well as young elk and deer. The only means of getting rid of them is by poison. This method will be tried during the winter." Deer and antelope were reported to be increasing. The statement was made that mountain lions ". . . are numerous and destroy much game. Several were killed last winter where the mountain sheep range." This is the first mention of official mountain lion control that has come to my attention although it was doubtless practiced earlier.

Supt. George W. Goode in the annual report for 1900 said that antelope were increasing even though many were wandering out of the park, where he felt they were almost sure to be shot. He appeared to be little concerned about coyote predation.

In the annual report of 1904 it is stated that the game animals were in good shape. The deer and bighorn were fed hay because of the shortage of range, and probably some antelope were fed hay but a definite statement on this was not found. In spite of the fact that the game animals appeared to be doing well and it was thought that the cougar preyed chiefly on the ubiquitous elk, the cougar were hunted with dogs, and 15 of them were killed, chiefly in the Mount Everts region. Concerning coyotes the following sentiment is expressed: "It is the general impression that coyotes are protected in the park, but this is far from true, for it is a well known fact that they are very destructive to the young game of all kinds, and we therefore use every means to get rid of them . . . They are also destroyed by the use of traps and poison, and during the past winter between 75 and 100 of these animals were killed."

The superintendent in his 1905 annual report was apparently somewhat tolerant of coyotes and cougar although control was practiced. He writes: "As the lions and coyotes are somewhat destructive to other game, such as elk, deer, and sheep, and also a pest to stockmen of the surrounding country, they are destroyed whenever the opportunity affords. The killing of these animals is, however, made a matter of business and not of sport, and only a few persons are permitted to do this killing, and they are scouts, and certain good shots among the soldiers."

The 1908 annual report shows that coyotes were still being killed, and that the cougar was again a rare animal. Following quotations are taken from this report: "It is a difficult matter to keep the coyotes down. Since my last annual report, which showed 99 coyotes killed in that year, 97 more have been killed. The growing scarcity of antelope, deer, and sheep in the States bordering on the park and the increase of these animals in the park causes the coyotes to gather here for their meat. One lynx was killed during the year. Also one red fox was shot by Scout Graham in the night time in mistake for a coyote . . . Mountain lions are scarce. One was killed during the year. It was no longer necessary to keep the pack of hounds purchased in 1893 for the extermination of mountain lions, and under authority from the department the pack was sold, after advertisement, to the highest bidder."

Official record of certain predatory mammals destroyed in Yellowstone National Park1

| From superintendent's annual report for— | Mountain lions | Coyotes | Wolves | From superintendent's annual report for— | Mountain lions | Coyotes | Wolves | |

|

1904 1905—6 1907 1908 1909 1910 1911 1912 1913 1914 1915 1916 1917 1918 1919 1920 1921 |

15 ... 1 ... ... ... ... ... 19 ... 4 ... 23 11 ... ... |

... ... 99 97 60 40 129 270 154 155 100 180 100 190 227 107 140 |

... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... (2) 14 4 36 6 28 12 |

1922 1923 1924 1925 1926 1927 1928 1929 1930 1931 1932 1933 1934 1935 Total |

... ... ... 1 ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 121 |

130 221 226 180 238 284 288 139 98 83 107 145 55 110 4,352 |

24 8 ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 132 |

1 Taken from Skinner 1927, p. 239, and

later official correspondence.

2 Several.

In 1909 the attitude of the superintendent in charge had changed. He wrote in his annual report: "Quite a number of coyotes were killed last year—about 60 in all—but still they seem to increase. It is doubtful, however, if they kill much game, as the deer seem to be able to protect themselves. On several occasions last winter, I saw deer chasing coyotes instead of being chased by them."

In 1912, by means of poison, traps, and shooting, 270 coyotes were killed and it is stated that many more still existed. The game animals had apparently been in good condition. A decrease in deer was noted in the fall of 1911 but this was probably correlated with the heavy mortality during the previous winter. More than 200 bighorn had been counted in the spring, many of which had been foraging outside the park.

The 1913 annual report states that 154 coyotes were poisoned, trapped, or shot. The 1914 report states that 155 coyotes were killed. Wolves were reported to have returned, and although none was killed, efforts were made to eliminate them. The cougar was again controlled by the use of dogs and 19 of them were destroyed. The big game animals were reported to be in good condition and thriving.

Predator control continued through the winter 1934—35. The last cougar was killed in 1925. Since that time definite authentic park records of cougar have not come to my attention. The last wolves were eliminated in the twenties although a few have been reported in recent years. Control was continued until the cougar and wolf and probably the wolverine, incidentally, were eliminated.

In line with the thought prevalent in the country today, there has evolved in the national parks the wildlife policy of basing any control of animals on thorough research.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

fauna/4/chap1.htm

Last Updated: 01-Feb-2016