|

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Fauna of the National Parks of the United States No. 5 The Wolves of Mount McKinley |

|

CHAPTER EIGHT:

GOLDEN EAGLE

THE GOLDEN EAGLE (Aquila chrysaetos canadensis) is one of the conspicuous members of the Mount McKinley National Park fauna. There are probably 25 or more pairs breeding in the mountain sheep hills. They arrive in March and depart in October, and rarely one may winter there. Because of the abundance of this bird it was possible to get quantitative data on its food habits and information concerning its relationships to the sheep and other animals.

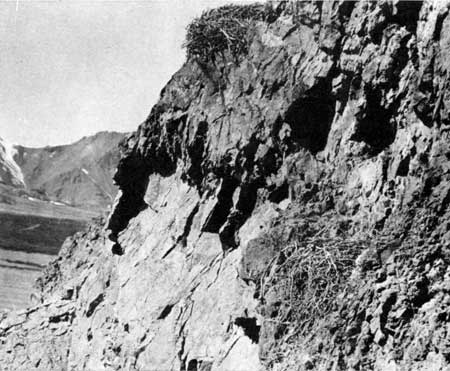

Figure 56: Two eagle nests in a typical

location on a cliff. The upper nest had not been used for some time and

was falling apart, but the lower one was in use for at least two

seasons. [Polychrome Pass, June 3, 1939.]

Nesting

All of the nests that were found were built in cliffs, which were located at various altitudes from the base of a ridge to near its summit. Some nests placed on perpendicular rock walls I was unable to reach, but others were easily accessible. A nest in a tree was reported but I did not see it. Frequently the rock surrounding a nest is orange colored because of the presence of a foliose lichen. Probably the moisture held by the nest favors the growth of this lichen. These orange-colored patches on the rocks on a few occasions first attracted my attention to the nest.

The same nest may be used in successive seasons, or it may be deserted a year or more and then used again. A nest in use in 1939 was vacant in 1940 and again in use in 1941, and another nest vacant in 1939 and 1940 was used in 1941. Sometimes a nest is deserted and a second one is built nearby. A nest occupied in 1939 and 1940 was deserted in 1941 and a new nest was built on a ledge a little lower on the slope. The addition of some branches of heather and dwarf birch to the old nest showed that the owner still took a little interest in it. In 1940 a new nest was built only a few yards from an old one which had been built up quite high and seemed in danger of falling off the ledge.

In 1939 five occupied nests were found; in 1940 three, and in 1941 five. Two nests used in 1939 were not visited the following two seasons, and one nest used in 1940 was not visited in 1941. During the 3 years 10 different nest sites were found in use. Thirteen other nests were found which were not in current use. The approximate location of several nests was known but there was not time to search for them.

In the nests observed, two young occurred more frequently than one. In five of them there were two young; in another one young and an unhatched egg; in another one egg, and in each of two nests there was a single young. In four nests it could not be determined how many young there were. A complete record of the survival of the young was not kept, but in at least two cases two young in a nest survived until fully feathered. A dead young one, just getting a few feathers, was found near one of the nests.

The eggs generally hatch in June, often in the latter part of the month. At one nest the egg did not hatch until about the middle of July and the young one was still in the nest on August 24. In a nest at Beal's Cache near McCarty in interior Alaska, O. J. Murie found a golden eagle egg hatched May 26. This is considerably earlier than any hatching date I noted, but possibly some eagles do nest that early in Mount McKinley National Park.

Home Range

In 1939 two occupied eagle nests were only about 1-1/2 miles apart, and in 1941 two pairs of eagles were nesting on the same slope of a ridge only about 1 mile apart. The distance between other occupied nests was sometimes less than 5 miles. With the nests so near one another it is obvious that there is considerable overlapping of ranges. Probably eagles nesting so near one another cruise over the same areas, although each pair may have favorite slopes over which they glide in search of ground squirrels. However, I would guess that eagles nesting near each other hunt indiscriminately over the slopes in the general region except perhaps close to a nest.

It is of course difficult to determine the size of the hunting area of a nesting pair. I have seen eagles fly off 4 miles from the nest site in a few minutes. It would seem highly improbable that the eagles confined their activities to an area less than 10 miles in diameter and I expect they may cruise considerably farther afield at times, especially when carrion is available. On June 16, 1940, near a wolf den, 7 eagles were gathered at carrion in one spot, and three others were feeding not far away. The nearest nest to the spot where they fed was almost 5 miles away. On June 28, 1941, 9 eagles were assembled at a carcass, and on July 2 there were 14 at a carcass.

Some of those eagles may have been nonbreeders but most of them appeared to be adults. (The 14 eagles were sitting in the rain. When the sun came out they half spread their wings to dry.) These assemblages during the nesting season indicate that many eagles feed over a common territory and that their ranges are quite extensive.

Food Habits

The food habits of the eagle were studied principally by examining the pellets they had regurgitated. The food remains at the nests were also noted, with special effort to find remains of lambs.

At the nests, both occupied and unoccupied, the following items were found: ground squirrel, 14; marmot, 6; snowshoe hare, 3; ptarmigan, 2; calf caribou, 2; lamb, 4. In two cases the lamb bones were found near the base of the slope under the nest and were old and weathered. These data on food habits are in general accord with those secured from the examination of pellets.

Eagle pellets collected over a 3-year period totaled 632—83 in 1939; 330 in 1940; and 219 in 1941. They were gathered from widely separated areas over the mountain sheep range so should be representative. A few were found at the eagle nests, some near the nest on prominent points used by the adults, and others along the ridges, generally on promontories used as perches. Above one nest there was a knife-edged ridge, with a rock escarpment on one side and a steep grassy slope on the other. More than 40 pellets were found along this ridge on grassy points used by the eagles. Prominent grassy knobs, sometimes far down the ridges, are favorite feeding perches and therefore good places to search for pellets. Sometimes as many as a dozen or more pellets were found together. The pellets contained the hair and bones of the animals eaten. Sometimes the entire foot of a ground squirrel was present. Some pellets were as large as 4 inches long and 1-3/4 inches thick, but usually they were slightly smaller.

TABLE 20.— Contents of golden eagle pellets collected in Mount McKinley National Park, 1939-41.

| Food item | Number of pellets in which each item occurred | |||

| 1939 (83 pellets) | 1940 (330 pellets) |

1941 (219 pellets) | Total (632 pellets) | |

|

Ground squirrel (Citellus p. ablusus) Marmot (Marmota e. caligata) Mouse (Microtine sp.) Caribou, calf (Rangifer a. stonei) Ptarmigan (Lagopus spp.) Small bird (including sparrows) Bird, sp. Dall sheep, adult (Ovis d. dalli) Dall sheep, lamb (Otis d. dalli) Snowshoe hare (Lepus a. macfarlani) Hawk, sp. Muskrat (Ondatra z. spatulata) |

60 6 7 6 11 1 2 3 |

284 18 17 17 4 3 8 6 2 1 1 |

200 13 8 1 6 9 1 2 2 |

544 37 32 24 21 12 9 9 6 3 1 1 |

Because of the large size of the eagle pellets and the great scarcity of hawks and owls in the sheep hills, there was little danger of any pellets being misidentified.

Table 20 gives the number of pellets in which each species was found in each of the 3 years. Except in the case of mice, only one individual of a species was found in a pellet. In the 632 pellets there were 699 occurrences, so that not more than 67 pellets contained more than one species. The findings during the 3 years are similar, so that it seems that a true picture of the food habits of the golden eagle in the park has been secured.

Annotated List of Animals Eaten by the Golden Eagle

Ground Squirrel.—The staff of life of the eagles in Mount McKinley National Park is the ground squirrel. In 1939 it was found in 72 percent of the pellets, in 1940 in 86 percent, and in 1941 in 91 percent. Of the 632 pellets gathered during the 3 years, 544 or 86 percent contained ground squirrel.

Ground squirrels are widely distributed over the sheep hills inhabited by the eagles, and occur from the river bars to the ridge tops. They are plentiful on the slopes where eagles may often be seen hunting for them, sailing along a contour close to the ground. In passing over sharp ridges one wing sometimes almost scrapes the ground as the eagle pivots to skim over a new slope. Its sudden appearance over a ridge probably is quite a surprise to many a ground squirrel.

Ground squirrels come out of hibernation in April and remain active until late September. One was seen as late as October 20. During most of the time that eagles are in the park ground, squirrels are available to them.

Hoary Marmot.—Marmot remains were found in 37 or 6 percent of the 632 pellets. If ground squirrels were not so readily available there probably would be a heavier toll on the marmots. On July 3, 1939, an eagle was seen eating an adult marmot, freshly killed, which showed that the old as well as the immature are taken.

Mouse.—There are four species of field mouse, a lemming, and a red-backed mouse in the park. During my stay, the field mice were by far the most numerous, so that most of the microtine remains probably belong to the genus Microtus. Mice were found in 32 pellets. The greatest number of individuals found in any one pellet was five. Once an eagle pounced on something in the grass which I took to be a mouse since a ground squirrel or bird could probably have been seen. When he struck he slid along for about 6 feet. He laboriously flapped away over the ground and after flying about 150 yards struck again at something in the grass, apparently another mouse. Mice were, in general, very scarce in the summer of 1939, but in 1940 and 1941 some species were again common.

Caribou.—Remains of adult caribou were not noted in the pellets, but I have several times seen eagles feeding on carcasses. The eagles assemble at any carrion they happen to find.

Calf caribou remains were found in 24 pellets. In 1941 only one pellet contained caribou. The scarcity of calf caribou remains in 1941 was correlated with the rapid passage of the cows through the park after they had calved. They were available as food in most of the area for a relatively short period. If a thorough search near the calving ground had been made more pellets containing caribou calf would, of course, have been found. Although some calves are killed by eagles, it is thought that these are generally stray animals which have lost their mothers. It was known that many of the calf caribou eaten by eagles were wolf kills. Predation of eagles on the calves seems insignificant. The relations between eagles and caribou have been discussed in the section dealing with caribou beginning on p. 162.

Figure 57: Male willow ptarmigan in

breeding plumage. [Igloo Creek, May 11, 1939.)

Ptarmigan.—Three species of ptarmigan are available. The willow ptarmigan (Lagopus lagopus alascensis) is usually the most abundant species but is subject to definite cycles so that its availability as a food supply varies over a period of years. From 1933 to 1941 it was relatively scarce. In 1939 it showed some increase in numbers which continued during the following 2 years. The rock ptarmigan (L. rupestris kelloggae) seemed less numerous than the willow ptarmigan, and the white-tailed ptarmigan (L. leucurus peninsularis) was scarce.

Ptarmigan remains were found in 21 or 3 percent of the pellets. Some of the unidentified feathers found in pellets may have been those of ptarmigan, but the percentage would not be changed much regardless. When ptarmigan are more abundant, especially when at the peak of their cycle, they probably constitute a larger percentage of the food supply. On two occasions eagles were seen feeding on a freshly killed ptarmigan which was still warm.

Figure 58: Male rock ptarmigan in winter

plumage. This species is generally found at higher elevations than the

willow ptarmigan. The latter is most plentiful along streams.

[Sanctuary River, May 20, 1939.]

Other Birds.—Twelve pellets contained remains of small birds, including sparrows, and the remains of a hawk were found in one pellet. In nine pellets the bird remains were too meager to indicate the species or the size of the bird eaten. Nesting birds were plentiful, so that there was considerable bird life available. The effect of the eagle on bird life is in significant.

Dall Sheep.—Nine pellets contained adult sheep which were eaten as carrion. Lamb remains were found in only six pellets. Although eagles are plentiful in the sheep hills, it is apparent that their predation on sheep is negligible. No authentic case of an eagle killing a lamb came to my attention. The relationship between eagles and sheep is discussed in Chapter III, (p. 97.)

Snowshoe Hare.—Snowshoe hare remains were found in only three pellets. Hares were extremely scarce within the area occupied by the eagles. When hares are abundant they will of course be a more important source of food.

Muskrat.—Muskrats (Ondatra zibethica spatulata) are scarce in the region studied and probably are generally scarce where the golden eagle nests. Remains were found in only one pellet.

Relationship of the Golden Eagle to the Park Fauna

The extensive data gathered on the food habits of the golden eagle from an examination of pellets, and the many observations made on habits, manifest that the eagle's relationship to the fauna is satisfactory from all viewpoints. Its effects on the other animals with which it is associated are all moderate, even on the ground squirrel which it hunts diligently.

Its predation on lambs and calf caribou is negligible. As pointed out in the chapter on caribou (p. 162), two calves were found which almost certainly had been killed by eagles. It appears, however, that there would be slight opportunity for an eagle to kill a calf accompanied by its mother. No case was found of an eagle killing a lamb, and observations indicate that such predation is rare.

The eagle has frequently been accused of being destructive to red foxes. A fox pup or even an adult might be taken occasionally but predation on foxes in Mount McKinley National Park is slight. This is shown by the absence of fox remains in the eagle pellets, also by the large flourishing fox population where the eagles are abundant.

Ptarmigan are preyed upon, but when they are scarce few are taken, and when they are numerous the species can stand a heavy predation.

The eagle often feeds on animals killed by wolves, but such robbing does not seriously affect the wolf. The amount eaten by eagles is probably directly related to the abundance of food available to the wolf.

The chief food of the eagle is the ground squirrel. If the ground squirrels were scarce the extensive predation on them by the eagle might be considered detrimental to the fox, bear, wolf, and other species which also prey on them. But there are enough for all, so that the eagles' feeding on them is perhaps useful in helping to curb their increase and maintain some sort of balance. It is likely that predators take the equivalent of the yearly increase among the ground squirrels, thus leaving an ample breeding population to transform vegetation into flesh for the meat-eaters in succeeding years. The continued high population level of the ground squirrels suggests that the predation is such as to maintain them at a high level by preventing their numbers from pyramiding and then going into a tail spin; also, the steady pressure maintained on them by the eagle and other predators may be sufficient to destroy the ailing animals should the species here be subject to disease. To a limited extent the ground squirrels do compete for food with the sheep, but at present such competition is not important. Should the ground squirrel become excessively abundant perhaps the competition with sheep would be significant, especially on many of the wind-blown ridges. To summarize, we might say that the predation of the eagle on the ground squirrel, its chief food, tends to be beneficial to the general interrelationships existing.

To us, the greatest value of the eagle consists in the pleasure of seeing it, or hoping to see it, in its mountain home. It is fortunate that the bird's economic status is also favorable.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

fauna/5/chap8.htm

Last Updated: 01-Feb-2016