|

CAPE LOOKOUT

Barrier Island Ecology of Cape Lookout National Seashore and Vicinity, North Carolina NPS Scientific Monograph No. 9 |

|

CHAPTER 3:

OVERWASH STUDIES AT CAPE LOOKOUT NATIONAL SEASHORE (continued)

Direct evidence of geomorphic and ecological changes can be found in many places on the Outer Banks. The "ghost forest" of Shackleford Banks is populated by picturesquely shaped remnants of cedar trees, in many places still standing on the old forest floor, and exposed as the dunes migrated away from these woodlands which they buried earlier in this century (Fig. 13). Such dead remnants are common on the seaward side of the existing woodlands along the western half of the island. More direct evidence of dramatic change is the layers of peat and stumps that frequently are found along the ocean beaches of the Outer Banks at low tide. Such an outcrop found on Shackleford (Fig. 14) indicated that a swamp forest of some type existed there around 200 years ago when sea level was lower and the beach much farther to the south. Likewise, stumps commonly found in what are now salt marshes along the back side of Shackleford, where old maps of the last century indicated living forests, are clear evidence of recent sea-level rise (Fig. 15). Such stumps are anchored in the sand, and tidal marsh vegetation has migrated onto what were once uplands.

|

| Fig. 13. Former forest on the west end of Shackleford. In early 1900, the forest was buried by dunes which have since migrated away, exposing remains of cedar trees and the forest floor. Such views are common on the southern half of the island facing the sea, and are direct evidence of once more extensive forest. |

|

| Fig. 14. Stumps and peat exposed at low tide on the ocean beach near the middle of Shackleford. The peat strata suggest formation under a wooded fresh water swamp; samples dated by Carbon-14 were less than 200 years old. Similar "drowned forests" are frequently seen along the beaches of the Outer Banks and other barrier islands. Salt marsh peat strata are likewise commonly found at low tide line on beaches. Peat exposures can be regularly found after severe storms on Core Banks. Such evidence indicates major physiographic changes, with marked retreat of the islands, and a lower sea level when the forests and marshes were alive. |

|

| Fig. 15. A salt marsh with tree stumps on the eastern end of Shackleford, where maps of a century ago showed forest. Rising sea level apparently changed a woodland to a marsh in that time. |

The eastern end of Shackleford once supported the "town" of Diamond City, abandoned in the later 1800s, and today, where the land was once wooded, there are grasslands and marshes. From the air, distinctive strips of open sand, back from the beach, can be seen along the eastern end of the seashore (Fig. 16). Such open strips are overwash fans consisting of sand pushed into the island from the beach. Old dunes can be seen in the foreground, with overwash passes between them. In areas such as this, and throughout the seashore, soil profiles show layers of organic matter below typical beach sand. In some places, such as the eastern half of Shackleford, the stumps of a destroyed forest stick up through the sand, surrounded by seedlings of the same species, Juniperus virginianus (Fig. 17). Diggings around these stumps show that the base of the tree and the old forest floor are indeed covered by sand from the beach, mixed with shells that could only have come from the surf zone. These woodlands were shown on 1850 maps (Fig. 11A), so we know they were alive then. The trees apparently died when sand was pushed in from the beach; the level of the land rose anywhere from 0.25 to 0.5 m, and the water table rose with the new deposits flooding out these mesophytic trees.

|

| Fig. 16. Western end of Shackleford showing a characteristic feature of most of the Outer Banks: overwash from high storm tides, the white area in the center of the photograph. This region was forested in the last century and was the site of Diamond City, abandoned in the early 1900s following severe hurricanes in 1899. Fig. 15 was taken in the marshes of this area. |

|

| Fig. 17. Many once-wooded areas of western Shackleford still have stumps and snags from the old forest. Soil profiles in these areas invariably show yellow beach sand and shells overlying the old forest floor and tree bases. The old surface in this profile was covered by 40 cm of beach sand. A young red cedar, Juniperus virginiana, shows on the left, and in time a new forest may grow up on this elevated surface. |

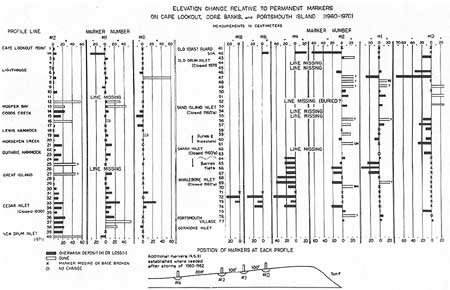

The rate of overwash build-up was determined from historical aerial photographs and from surveys of change in elevation relative to permanent bench marks established by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in 1960 between Cape Lookout and Ocracoke Inlet. The Corps set out 77 lines of these bench marks perpendicular to the beach and 3000 ft (914.4 m) apart, with three or more markers in each line 100 ft (30.5 m) apart. Each iron pipe marker had a concrete base poured around it at the level of the sand when the pipe was installed, so that changes relative to these concrete bases can be determined (Figs. 18 and 19). All lines still in place were evaluated. Some of the markers had been damaged during severe storms of the early 1960s, but these were evaluated by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in their project report (U.S. Army Corps of Engineers 1964). Since that time, no others have been lost to the sea, although beach buggies have knocked down a good many. Of the markers still left, we found that the overwhelming majority located some distance from the beach was buried by overwash deposits alone or overwash combined with dune build-up (Fig. 20). Of the markers nearest the beach approximately one-third were eroded, one-third showed no change, and one-third were buried. On the average, the markers from Swash Inlet (south of Portsmouth Island) to Cape Lookout had definite sand build-up around them, but those on Portsmouth Island showed erosion. The southern region has thick grasslands and a low, irregular dune line, while the Portsmouth region is barren and mostly without dunes. Thus, where there is some resistance to water flow, overwash appears to build up the land, yet where there is no resistance, surface erosion can occur.

|

| Fig. 18. Profile 14 on Core Banks, showing the bench marks established by the Corps of Engineers in 1960, and elevation changes. When constructed, the concrete base was at the level of the sand. Profile 14.0 in the foreground is now located in an overwash channel and shows some loss of sand from the base; 100 ft back is P 14.1, just visible in the photograph. Sand covers the base of this marker. |

|

| Fig. 19. Marker P 14.2, 200 ft from P 14.0, was nearly totally buried by layers of sand washed in from the beach when the photograph was made in 1969. The concrete base is visible at the bottom of the hole. The ruler is 15 cm long. A year later the cap was completely covered. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

chap3a.htm

Last Updated: 21-Oct-2005