|

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Research in the Parks NPS Symposium Series No. 1 |

|

Winter Weather as a Population-Regulating Influence on Free-Ranging Bison in Yellowstone National Park

MARY MEAGHER, Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming

INTRODUCTION

The present bison (Bison bison) population in Yellowstone National Park is wild, unrestricted by boundary or internal fences; and since 1966, subject to no regulatory influence from man. The history, population characteristics, habits, and habitat relationships of the Yellowstone bison have been reported from studies that were carried out from 1963 through 1968 (Meagher 1970). These studies documented that the indigenous population of mountain bison persisted, although poached to near-extermination by about 1902. Plains bison were introduced in 1902 and ultimately mixed with native animals. From 1902 to 1966, management varied in objectives, intensity, and population units affected, but generally decreased. Management to control bison numbers (reductions) involved removing what were considered surplus animals.

The 1963-68 studies suggested how the park's original bison population was naturally regulated and indicated that all population units did not need to be controlled. Subsequent work has shown in more detail the degree to which one environmental factor, severe winter conditions, affects the bison population.

POPULATION UNITS AND WINTERING AREAS

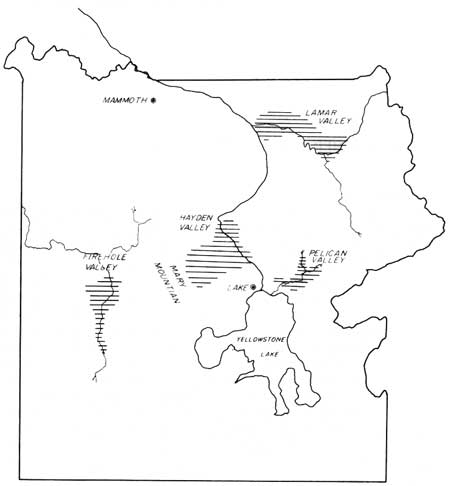

The bison population is separated into three units according to wintering location. These are the Pelican, Mary Mountain (which includes Firehole and Hayden valleys), and the Lamar areas (Fig. 1). These population units are not geographically isolated, but interchanges of animals are limited because of their habitual use of specific wintering areas.

|

| Fig. 1. Bison wintering valleys in Yellowstone Park. |

Pelican Valley lies at an elevation of 7800 ft. Meadows of sedge (Carex sp.) and grass are the main vegetation on the valley floor. Hills and trees are few within this shallow basin. Occasional stands of willow (Salix sp.) do not project above winter snow levels. Coniferous forest borders the valley and also covers the mountains which rise to the north and east.

The centrally located Mary Mountain area includes two well-defined valleys, bordered by extensive coniferous forest. Hayden Valley, at 7700 ft, is drained by two major streams. Its varied terrain has interspersed meadows and sagebrush-covered (Artemisia tridentata) hills. Scattered stands of coniferous forest also grow within this otherwise open valley. West across the low divide formed by Mary Mountain lies the Firehole area, at 7200 ft. Open meadows and coniferous forest are considerably interspersed within this long, sometimes narrow, rather flat-bottomed valley.

Lamar, at an elevation of approximately 6400 ft. is the largest valley, with quite varied terrain. Mixtures of sagebrush and grass cover extensive hills and lower mountain slopes. Coniferous forest grows on higher slopes. Willows grow along streams; aspen (Populus tremuloides) groves occupy limited sites within the sagebrush-grassland or at the edges of coniferous forest stands.

WEATHER CONDITIONS

Winters throughout the park are generally long and cold. A 30-year mean annual January temperature of 39.8°F is recorded for the headquarters station at Mammoth near the north boundary (Weather Bureau 1930-59). Temperatures at this station average about 5°F higher than those for most of the park. Most precipitation occurs as snow. For most of the park, between the 7000 and 8500-ft levels, the average snowfall is about 150 inches, with Lamar averaging 85-95 inches, and Lake, near Pelican, averaging 146 inches.

Weather stations and snow courses are not at locations which allow a direct comparison of weather conditions prevailing on all of the bison wintering areas. An assessment of the various available records, together with personal knowledge, indicates that winters are consistently more severe in Pelican and Hayden valleys, less so on the Firehole, and comparatively moderate in the Lamar.

Weather and snow course records from Lake, just west of Pelican Valley, permit a more detailed description of this one area. Snow covers the ground from late October to early May, sometimes later. Snow depths in the valley are usually a few inches deeper than those of the Lake snow course. Average mid-winter snow depths for Pelican Valley are about 40-45 inches; snow course averages for February and March (taken about the first of each month) from 1949 through 1967 were 33 and 38 inches, respectively (Table 1). Rangers reported 75-80 inches of solid, wind-packed snow in Pelican Valley during March 1943. A maximum of 64 inches is recorded for the Lake snow course in early February 1943. Data from Lake station indicate minimum daily temperatures below zero and high winds (actual velocities not recorded) on one-third to one-half of the days each month for January, February, and March. Pelican Valley lies exposed for its entire length to the sweep of the prevailing west and southwest winds. Ranger reports and personal experience indicate that heavy crusting may occur with warm spells from early March into April (Meagher 1971).

Data from the Lake snow course (Table 1) provide a basis for evaluating relative severity of Pelican winters. Snow depth, density of snow as indicated by water content, length of winter, and lateness of spring (May snow depth) contribute to the evaluation. The records show an extremely severe winter occurred once in the last 35 years. Winters rated as severe may occur more or less every 20 years. Winters of above average severity can be expected two or more times each decade.

TABLE 1. Lake snow course measurements (inchs). Depths are for the beginning of the month shown (Soil Conservation Service 1919-67; NPS 1969-71).

| Winter | Snow course No. | January |

February |

March |

April |

May |

Kind of winter | ||||||||||

| Depth | Water content | % 15-yr. avg. | Depth | Water content | % 15-yr. avg. | Depth | Water content | % 15-yr. avg. | Depth | Water content | % 15-yr. avg. | Depth | Water content | % 15-yr. avg. | |||

| 1937-38 | #1 | 41 | 10.6 | 27 | 10.3 | Moderately severe | |||||||||||

| 1942-43 | #1 | 64 | 17.7 | (est.) 19.7 | 61 | 20.7 | Extremely severe | ||||||||||

| 1948-49 | #1 | 30 | 7.4 | 35 | 8.1 | 43 | 12.5 | 47 | 15.2 | 21 | 7.6 | Moderately severe | |||||

| 1951-52 | #1 | 33 | 5.8 | 40 | 9.6 | 46 | 12.8 | 53 | 14.6 | 22 | 7.9 | Moderately severe | |||||

| 1955-56 | #1 | 40 | 10.2 | 56 | 15.0 | 59 | 17.5 | 53 | 18.2 | 41 | 15.2 | Severe | |||||

| 1961-62 | #1 | 29 | 5.8 | 36 | 7.8 | 50 | 12.0 | 53 | 14.4 | 32 | 9.9 | Moderately severe | |||||

| #2 | 27 | 5.5 | 33 | 7.3 | 47 | 11.2 | 50 | 13.4 | 26 | 7.7 | |||||||

| 1964-65 | #1 | 34 | 7.1 | 52 | 12.1 | 51 | 14.4 | 51 | 15.8 | 39 | 14.0 | Moderately severe | |||||

| #2 | 32 | 5.7 | 49 | 10.9 | 48 | 13.2 | 48 | 15.0 | 36 | 13.4 | |||||||

| 1968-69 | #2 | 21 | 3.8 | 108 | 47 | 10.4 | 179 | 46 | 12.6 | 154 | 42 | 14.0 | 141 | 21 | 8.7 | 112 | |

| 1969-70 | #2 | 13 | 1.5 | 43 | 26 | 4.6 | 79 | 25 | 5.4 | 66 | 37 | 8.5 | 85 | 42 | 10.8 | 138 | Moderate except late spring |

| 1970-71 | #2 | 29 | 6.2 | 177 | 38 | 9.8 | 169 | 44 | 1.8 | 143 | 52 | 15.0 | 152 | 43 | 16.5 | 212 | Severe |

| Est. avg. #1 1947-67a | 23 | 4.3 | 33 | 6.8 | 38 | 9.2 | 41 | 11.3 | 28 | 8.9 | |||||||

| Depths used for selection of severe winter | 30 | 40 | 40 | 45 | 40 | ||||||||||||

aData unavailable for specific months some years. | |||||||||||||||||

INFLUENCE OF WEATHER ON BISON

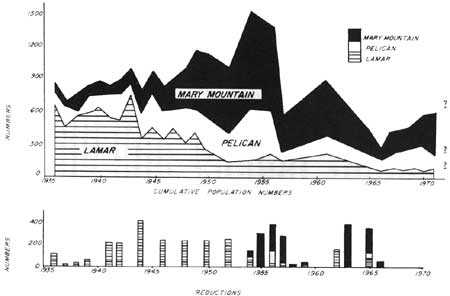

Population trends based on census data from 1936 through 1971 for all three population units, together with reduction numbers, are shown on Fig. 2. Projected numbers for 1972, based on interim counts, are included. Decreases in all population units between 1956 and 1957, which are most striking in the Pelican and Mary Mountain units, coincided with the severe winter of 1955-56. The occurrence of reductions did not adequately explain the decreases. Reported winterkill as an indicator of the amount of late winter mortality suggested the effects winter conditions could exert. Emigration, disease, and predation are not factors with noticeable effect on the Yellowstone bison.

|

| Fig. 2. Bison population trends 1936-71. |

a. The Pelican Valley Herd

The Pelican unit offered the best opportunity to determine how a bison population is naturally regulated. Historical records show this area has had a wild bison population continuously since the park was established, and probably long before. Recovery from the near-extermination about 1902 occurred naturally. Reductions have been held here only twice since this time. Bison are the only ungulate which winters within this valley.

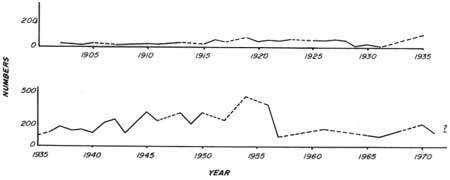

During the 15 years since the severe winter of 1955-56 Pelican bison numbers have fluctuated between approximately 100 and 200 animals (Fig. 3). A reduction of 34 animals was made in 1965; no other control has occurred. The 1965 reduction coincided with a moderately severe winter and a population decrease. After an increase between 1966 and 1970, the population has again decreased.

|

| Fig. 3. Pelican area wintering bison numbers 1902-71. |

Mortality, largely due to winter weather conditions during two succseeding years, has been the major factor in causing the recent decrease in the Pelican population. The winter of 1969-70 was of below average severity until spring. Snow depths at the beginning of May were well above average (Table 1), and storms were continuous during the first half of May after calving had begun. Calf percentages at the beginning of June were the lowest of those recorded since 1965 (Table 2). Difficulty in obtaining percentages of calves at the end of calving season in late June precludes using exact figures but later aerial surveys confirmed that Pelican calf numbers were low by several percent. The same late winter conditions caused higher than usual mortality among other age classes, as indicated by an early summer ground survey. Aerial counts showed that the decrease in animals older than calves was 15-20%.

TABLE 2. New-calf ratios as percentages of mixed-herd numbers in Pelican Valley, 1965-71.a

| Date | Herd total | % calves |

| 1965, 2 June | 69 | 14 |

| 1966 | —— | —— |

| 1967, 4 June | 96 | |

| 1968, 2 June | 111 | 11 |

| 1969, 21 May | 129 | 12b |

| 1970, 3 June | 131 | 10 |

| 1971, 2 June | 118 | 13 |

aMixed herds are predominately cows, subadults, and calves. Usually

some mature bulls are included.

bExpected to be slightly higher by early June. | ||

The following winter, 1970-71. was rated as severe in the Pelican area. Aerial and ground counts between February and early April suggested that approximately one-third of the population (about 50 animals) had died. Subsequent aerial counts confirmed the magnitude of the mortality. The number of winterkilled animals found during early summer also indicated that substantial mortality occurred. Only 14 carcasses of all ages were located, but this compares with the 1 or 2 old bull carcasses found after average winters.

b. Other Herds

In contrast to the Pelican herd, the effects of recent winter conditions on the Mary Mountain and Lamar herds were less apparent. The Mary Mountain population has increased in numbers since 1966. This was mainly in the Hayden Valley wintering segment, which is consistently much larger than the part of the Mary Mountain population which winters in the Firehole area. Essentially the same climatic factors apply to Hayden Valley as to Pelican, but the habitats differ. In spite of late storms during the spring of 1970, calf losses were not apparent in the Hayden Valley segment. More than usual numbers were winterkilled during the winter of 1970-71, but this was not sufficient to prevent the population from increasing. No unusual mortality was apparent in the Firehole segment in 1970 and 1971.

In the Lamar area, bison population numbers at present suggest stability; however, a slow increase in the proportion of the population formed by herd groups is occurring. The late storms in the spring of 1970 were less severe in this area and had no apparent effect on this population. The winter of 1970-71 was less severe than average; winter-kills were no more than usual.

DISCUSSION

The ecological literature contains numerous discussions on the natural regulation of populations. Such regulation probably results from a complex of intrinsic and extrinsic factors (Slobodkin 1962). Within Yellowstone National Park, three population units of bison show three different recent population trends. This suggests that the natural factors which influence population size vary among the three.

Data from the last 2 years support the hypothesis that winter weather is a major population-regulating influence on the Pelican bison population. Although periodically severe winters have marked effects on population size, census records suggest that approximately 100 animals may survive the most severe winters that occur. Scattered, small, thermal areas, both within the valley and in the surrounding coniferous forest, may be the habitat factor which permits a bison population to persist in the Pelican area over time (Meagher 1970, 1971). The effects of severe weather on bison mortality may be only partly density-independent, because deaths are limited to numbers in excess of the threshold carrying capacity of animals. This threshold of carrying capacity beyond which severe weather does not increase mortality may be largely determined by the amount of thermal ground within the Pelican Valley area.

Although winter weather conditions are similar in the Pelican and Hayden valley areas, the terrain and interspersion of different vegetation in Hayden Valley are more varied. The more variable winter habitat apparently provides increased opportunities for bison to secure food and survive. Additionally, some bison leave Hayden Valley in late winter, crossing to the Firehole side where weather influences are less severe. Such movements occurred between late March and early May in 1970 and 1971. However, the population decrease of 1956-57 suggests that severe winters will periodically reduce the numbers of bison in the Hayden Valley segment. Since winters that depress population numbers may occur less frequently in Hayden Valley, additional unknown factors must be influencing bison population fluctuations. The usual range of population fluctuations may be 400-600; conditions which permitted a population high of 858 bison in 1954 may not occur again (Meagher 1970).

In Lamar, where winter conditions for bison are least severe, other extrinsic and intrinsic factors may have a greater regulatory influence on bison numbers. The habitat would seem to favor a larger bison population than that which inhabits the Mary Mountain area, yet population trends since 1952 suggest that the usual winter number approximates 200 bison. Large numbers of elk (Cervus canadensis) also winter in the Lamar Valley, as do some bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis), mule deer (Ococoileus hemionus), and moose (Alces alces). Interspecific competition for food and/or space may partly set upper limits on bison numbers.

In conclusion, the main regulatory influence on the Pelican bison herd appeared to be frequent severe winter weather. Thermal areas and probably some other habitat factors provided a threshold carrying capacity which permitted about 100 animals to survive the most severe winters. The effects of weather on other population units were less pronounced because habitat conditions were more varied, or winter conditions were not as severe compared to the Pelican area. A complex of weather, other extrinsic effects, and intrinsic behavioral responses appeared to interact to regulate the numbers in these other population units.

REFERENCES

MEAGHER, M. 1970. The bison of Yellowstone National Park: past and present. Ph.D. Thesis. Univ. of California. Berkeley. 172 p.

______. 1971. Snow as a factor influencing bison distribution and numbers in Pelican Valley. Yellowstone National Park. Pages 63-67 in Proc. Snow Ice Symp. 11-12 Feb. Iowa State Univ. Ames.

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE. 1969-71. Snow course reports. Yellowstone National Park files.

SLOBODKIN, L. B. 1962. Growth and regulation of animal population. Holt, Rinehart and Winston. New York.

SOIL CONSERVATION SERVICE. 1919-67. Summary of snow survey measurements, Wyoming. SCS, Casper, Wyoming. 152 p.

WEATHER BUREAU. 1930-59. Climatological summary for Yellowstone National Park. Climatography of the United States. No. 20-48. 2 p.

Acknowledgments

Glen Cole and Douglas Houston of Yellowstone National Park provided valuable comments on this manuscript. Dave Stradley, Gallatin Flying Service, is responsible for the quality of the aerial surveys. This paper is a contribution from the National Park Service, Office of the Chief Scientist. Project Yell-N-8a.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

chap3.htm

Last Updated: 1-Apr-2005