|

GEORGE ROGERS CLARK

Selected Papers From The 1983 And 1984 George Rogers Clark Trans-Appalachian Frontier History Conferences |

|

"Michel Brouillet, 1774-1838: A Vincennes Fur Trader, Interpreter, and Scout"

Richard Day

Curator, Old French House, Vincennes

In 1974 the only surviving example in Indiana of a French Creole style house was discovered at Vincennes. Unlike the familiar log cabin with its horizontal-log construction, the early French settlers in the Mississippi Valley brought with them from Canada a traditional style of architecture, consisting of vertical posts with a mud-and-straw daubing in between. The house at Vincennes was built about 1806 by a fur trader named Michel Brouillet. In 1975 the house was restored by the Old Northwest Corporation, a local historical society, and in 1976 the house was opened to visitors as "The Old French House — The Home of Michel Brouillet."

Michel Brouillet was not a famous historical figure like George Rogers Clark or William Henry Harrison. If his house had not survived, it is doubtful that anyone — other than his descendants — would be aware that he even existed. However, this very fact of the original owner's humble background is one of the principal charms of the Old French House. "This is the kind of house I probably would have lived in if I had been living back then," is the comment frequently made by visitors to the house.

The Michel Brouillet who built the Old French House was the son of Michel Brouillet, Senior, who was born in Canada about 1742, and came to Vincennes in 1761. [1] The French commander at Vincennes, Louis Groston de St. Ange de Bellerive, granted Brouillet a verbal title to a farm near Vincennes. Brouillet also seems to have had a trading post in the 1760's on the Wabash River north of Terre Haute, on a creek that still bears his name, Brouillett Creek. [2]

Vincennes prospered with the revival of the fur trade following the end of the French and Indian War. The population went from 75 inhabitants and their families in 1757, to 232 men, women, and children (and 168 "strangers") in 1767, to 621 inhabitants in 1778. [3] Michel Brouillet, Senior, prospered as well. On May 1, 1773, Brouillet was able to pay 1,200 livres (about $240) for a house of posts in the ground, with "a plank roof not yet completed," and many smaller buildings, on a lot 16 toises (about 102 feet) square, facing the main street of the town, St. Louis Street — modern-day First Street. [4] The house stood on the south side of the street, halfway between modern Main and Busseron Streets, Brouillet bought the house from Charles Boneau, the father of Marie Elizabeth "Barbe" Boneau, the newly married Mrs. Brouillet. This was where Michel Brouillet, Junior, was born on 14 August 1774. [5]

On May 19, 1777, the new British Lieutenant-Governor of Vincennes, Edward Abbott, arrived and set out to make up for the previous 14 years of neglect by the Colonial administration. He trooped the inhabitants into the little log chapel of St. Francis Xavier, where they swore allegiance to King George and Abbott organized them into three militia companies of 50 men each. Then he built a fort, about 200 feet square, which he named in honor of Lord George Sackville, British secretary for the colonies. [6] Michel Brouillet, Senior, was given a commission as a lieutenant in the militia. [7] It was at this time that Brouillet was granted a farm on the "Chemin de Glaize" ("Lick Road") three miles northeast of town. [8]

Abbott, however, lacked money to purchase the gifts which visiting Indians expected to receive, and so, in February 1778, he was obliged to leave. [9] The power vacuum did not long remain. In July of 1778, Col. George Rogers Clark's army captured the posts of Kaskaskia and Cahokia, and on July 20, 1778, influenced by representatives sent by Clark, 184 citizens of Vincennes, including Michel Brouillet, trooped into the chapel, renounced their allegiance to King George and swore to be true subjects of Virginia. [10] Michel Brouillet was given a commission as a lieutenant in the militia from the Americans. [11]

However, Henry Hamilton, the Lieutenant-Governor of Detroit, was determined not to let these posts remain in the hands of the rebels. Assembling a combined force of royal troops, Detroit militia, and some 350 Indians, he descended the Wabash. Lieutenant Brouillet had been sent up river to watch out for any approaching troops, but he unluckily fell into the hands of Hamilton's Indian scouts on December 15, 1778. Brouillet's pockets were searched and two commissions were found, one from Abbott and one from Clark. Hamilton was angered by what he considered Brouillet's duplicity: "I should not certainly have hesitated at the propriety of hanging this fellow on the first tree but for two reasons — I was unwilling to whet the natural propensity of the Indians for blood, and I wished to gain the perverted Frenchman by lenity." [12]

When Hamilton arrived at Vincennes the next day, he found the fort defended by only one officer and one man. The French militia elected not to fight against an overwhelming force. They stacked their arms and trooped into the chapel to kiss the silver crucifix and again swear allegiance to King George. Confident of his superiority, Hamilton dismissed most of his forces for the winter. This was a mistake, for in late February of 1779 Clark made a surprise attack and captured the fort after a brief siege. The French once more swore allegiance to Virginia, and Brouillet was again made a lieutenant in the American army. Though he was less than five years old at the time, Michel Brouillet, Junior, later claimed he could well remember the events that occurred. From the porch of his home, little Michel could look down the street to the house on the corner of St. Louis and Jerusalem Streets (now First and Main), where Clark's headquarters was during the siege, and in front of which Clark's men killed five Indian prisoners. [13]

On June 24, 1779, Michel Brouillet, Senior, was promoted to Captain of Militia as a reward for his fidelity and courage. [14] And later, in September, Captain Brouillet was put in charge of a company of militia, under Captain Gamelin, on an expedition to Ouiatenon (now Lafayette), to prepare the way for Clark's projected attack on Detroit. [15] But the attack did not materialize, because of a lack of reinforcements from Virginia and the Kentucky settlements. [16] The rest of the war at Vincennes consisted of isolated Indian attacks, and, what for the French was probably almost as bad, the requisitioning of supplies by Virginia troops, who insisted on paying for it with worthless Continential currency.

In 1785, Father Pierre Gibault came to live in Vincennes, and he set up the first school in town. From him Michel Junior probably learned to read and write, and on May 30, 1785, the ten-year-old Michel signed his name for the first time on the church records, as the godfather of his sister Genevieve. [17] This literacy was to prove useful for Michel, as few of the local French could even sign their names.

In 1795, young Michel was hired as a clerk for Detroit fur trader Antoine Lasselle. [18] The clerk had an important part in the fur trade, since much of the business was on credit, and accurate records were essential. Beside keeping the books at Lasselle's storehouse (interestingly, the same building which Clark had used as his headquarters), the clerk was expected to go up river to check on the trading posts at the Indian villages. One of these would have been Hyacinthe Lasselle's post at the mouth of the Vermillion River. [19]

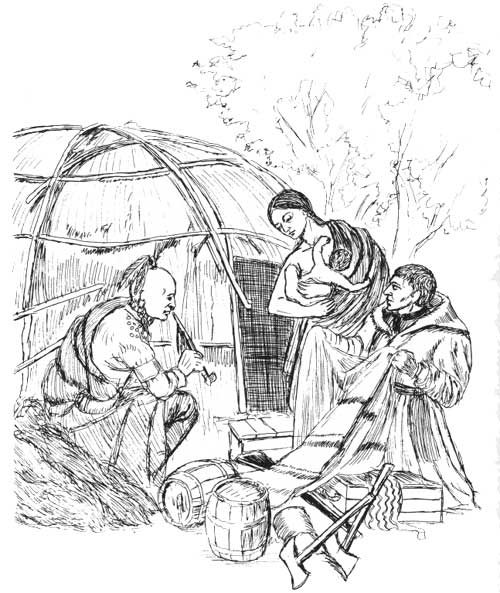

It may have been on one of these expeditions upriver that Brouillet met his Indian wife. According to family tradition, Brouillet was captured by the Indians, who were preparing to torture him, when he was rescued by a squaw. [20] This story may be true, since Indian women traditionally had the right of selecting prisoners, usually to replace dead family members. But it may also be that Brouillet took an Indian wife voluntarily, according to the "custom of the country." Taking an Indian wife was a good way to seal a trade alliance with the tribe and get preferential trading terms as well as receive advance warning of any hostilities that might be planned. Whatever the reason, it seems likely that in 1796 young Michel fathered the half-French, half-Miami Indian, Jean Baptiste Brouillette, who later became a noted Baptist preacher and the son-in-law of Frances Slocum, the "Lost Sister of the Wyoming." [21]

The next year Michel Brouillet, Senior, died and was buried on 6 January 1797, "amid tears and sobs," as the church record notes. [22] By this time the family had moved to the corner of Second and Busseron [23] where Michel shared the home with his widowed mother, and after her death on October 8, 1802, [24] with his brother-in-law Joseph Barron.

With his arrival in Vincennes in December 1800, Indiana Territory Governor William Henry Harrison was faced with the task assigned him by President Jefferson of acquiring land from the Indians upon which to settle the land-hungry settlers. One tool that Harrison decided to use was the licensing of selected traders. In this way, he could eliminate or reduce the influence of traders who might counsel the Indians to resist American land acquisition.

On December 12, 1801, Michel Brouillet was given a license to trade with the "Miami" nation at their town of Renaud. [25] This was probably a mistaken reference to the Kickapoo village of Joseph Renard, near the mouth of the Vermillion River. On May 1, 1803, Harrison appointed Brouillet as an interpreter at the treaty that he held at Fort Wayne in June of 1803. The French interpreters were an essential element in the treaties to persuade the Indians to go along with the land cessions. In this treaty, the Indians ceded the land around Vincennes. Brouillet did not sign the actual treaty, but was probably active persuading the Indians. He may have tried too hard. On October 6, 1803, Brouillet was dismissed for "drunkenness, keeping bad company, and neglect of his duty." [26] This apparent black mark did not prevent the Governor on July 10, 1804, from granting Brouillet another trade permit with the Kickapoo Indians in their towns on the Vermilion, although he did write in the provision "All Spirituous liquors prohibited." [27]

Nor did any doubts the governor may have had stop him from using Brouillet as interpreter in a treaty on December 30, 1805, at Vincennes with the Piankashaw Indians, in which they ceded a large part of eastern Illinois. [28] Probably few men other than Brouillet had the confidence of the Indians. Be that as it may, Indian resistance to Harrison's aggressive land-acquisition policies was beginning to develop.

In early 1805 the Shawnee Prophet began to preach that he had had a revelation from the Great Spirit, who told him that the Indian's salvation from the White Man could only come from turning away from the white man's ways and his goods, especially his whiskey. [29] Those Indians who had converted to Christianity were identified as witches in the power of the "Evil Serpent," and some were put to death. The new religion spread like wildfire among the Delaware on the upper White River. In late 1806, Moravian missionaries witnessed the persecution and martyrdom of some of their converts, and soon there was strong pressure for the missionaries themselves to depart. Helping them in their withdrawal from the White River to Cincinnati, from September 16 to November 12, 1806, was a French trader named "Bruje" (in German spelling) who had an Indian wife in one of the villages. [30] This may have been Michel Brouillet, whose Indian wife was recorded as being on the nearby Mississinawa River in the early 1800's. [31]

In any case, 1806 is also the year when Michel Brouillet took a French wife, at Vincennes: Marie Louise Drouet de Richerville, of an old Vincennes family. [32] And, quite likely it was in 1805 or 1806 that Brouillet had the "Old French House" built on First Street, between Seminary and Hart Streets. [33] The house was probably built by a professional carpenter and was rather nice for its time, costing about $450. In this house were born eight children, six of whom survived infancy, descendants of whom are yet with us.

On August 18, 1807, Michel Brouillet was appointed Captain in the first Battalion of the first Regiment of the Knox County Militia. [34] This was a position that he always treasured, and in later years he went by the name "Captain Brouillet." After his death, among his effects was listed an officer's sash, which he probably proudly wore during parades and militia exercises.

Soon Brouillet was in trouble again. The Quakers had undertaken to "civilize" the Indians on the Mississinawa, by teaching them White Man's methods of farming. The experiment was perhaps doomed to failure, but the Quakers chose to put some of the blame on Brouillet in a letter they wrote from Fort Wayne to the Secretary of War on 26 May 1808:

"There is little or no attention paid to the Law prohibiting the introduction of spirits liquors into the Indian Country, it is sometimes sold to the Indians at this Post yet no notice has been taken of it, the White people treat this Law with great contempt, many alleging that the sooner the Indians are destroyed the better, and scarcely care by what means this is effected, it would take up too much time to notice in detail the many instances where whiskey has been introduced into the Indian Country in violation of Law and in utter contempt of the public authority one case which has occurred since the arrival of Friends at Fort Wayne will be noticed as a specimen only — A certain Michel Brouillet of Vincennes was engaged by Governor Harrison to deliver a quantity of salt on Account of the US. at "Dennis's Station" near the forks of the Wabash for the use of the Indians in the month of April last it appears that in ascending the river from Vincennes he disposed of nineteen Kegs of Whiskey at Massasinway and other Villages on the River to the Indians, carrying away in return an immense quantity of skins, and thereby depriving the Indians of the means of paying their just debts and [purchasing] necessaries for their families — The scenes that were acted at Massasinway after the receipt of this liquor are well known to Friends and are unnecessary to detail here — this same Brouillet was once an Interpreter at the U.S. Trading House Fort Wayne and was dismissed therefrom for drunkenness and other bad practices." [35]

In April of 1808, the Prophet moved with his followers from Ohio to a new village called the Prophet's Town, on the upper Wabash River, at the mouth of the Tippecanoe River. He did this as much to remove his followers from the corrupting influences of the Whites as to, as he put it, keep a closer eye on the White/Indian border. [36] In August the Prophet paid a visit to Harrison at Vincennes, and reassured him of his motives to the extent that the governor supplied him with grain to feed his starving followers. Harrison confided that the Prophet might even be a useful tool for the United States. Just to be sure, on May 16, 1809, Harrison dispatched a "confidential Frenchman who speaks the Indian languages" to reside at the Prophet's Town for a few weeks to watch his movements and to discover his politics. [37] This "confidential Frenchman" was Michel Brouillet, and, this marked his entrance into the dangerous career of spying.

Harrison apparently received reassuring news from his spy, for on September 30, 1809, he conducted a treaty at Fort Wayne and purchased a large tract of land around Terre Haute. [38] By December, he was planning to dismiss Brouillet on his return from Prophet's Town and replace him with his brother-in-law Joseph Barron, whom he considered a better interpreter. [39] However, in April of 1810 Brouillet brought alarming news from Prophet's Town — the Indian forces were massing, perhaps for an attack on Vincennes. [40]

In a letter to the Secretary of War dated 25 April 1810, Harrison reported:

I have lately received information from sources which leave no room to doubt its correctness, that the Shawnee Prophet is again exciting the Indians to Hostilities against the United States. A Trader [Michel Brouillette] who is entirely to be depended on, and who has lately returned from the residence of the Prophet, assures me that he has at least 1000 Souls under his immediate control (perhaps 350 or 400 men) principally composed of Kickapoos and Winebagos, but with a considerable number of Potawatimies and Shawnees and a few Chippewas and Ottawas.

The friends of the French Traders amongst the Indians have advised them to separate themselves from the Americans in this town lest they should suffer from the attack, which they meditate against the latter.

I have no doubt that the present hostile disposition of the Prophet and his Votaries has been produced by British interference. It is certain that they have received a considerable supply of ammunition from that source. They refused to buy that which was offered them by the Traders alleging that they had as much as they wanted, and when it was expended they could get more without paying for it and the former appeared to the traders to be the fact, from the abundance the Indians seemed to possess." [41]

In early May, Brouillet was again dispatched to spy on the Prophet, and since the governor thought there was danger of Brouillet getting killed, he also sent another Frenchman as a backup. [42] Things began to heat up: on June 14, Brouillet reported that there was 3,000 men within 30 miles of Prophet's Town, who were constantly in council. Their plans were secret, but it was thought that they would at least try to prevent the American surveyors from getting on the newly acquired land.

The next day the boat that had been sent up river to carry the salt annuity as partial payment for the land, returned, having been sent back. [43] For the first time, Tecumseh, yet identified only as "the Prophet's brother," made himself noticed. He told the boatmen to load the salt back on the boat, and while they were doing so he seized them by the hair, shook them, and asked violently if they were Americans. (Fortunately they were French.) Then the Indians called Brouillet "an American dog" and plundered his store of its provisions. "Brouillettee is not known as an agent of mine by the Indians. He keeps a few articles of trade to disguise his real character," commented Harrison. Obviously, however, the Indians were beginning to suspect him.

Harrison called out the militia, but the following week, Brouillet arrived from Prophet's Town with reassuring news; he had erred in his estimate of the Prophet's followers: there were no more than 650, and the Prophet had been at pains to assure the governor that he had no hostile intentions. In order to reassure the populace, Harrison allowed Brouillet's report to be printed in the Vincennes Western Sun newspaper, thus uncovering Brouillet's role as a spy. [44] In the place of Brouillet, Harrison sent first Toussant Dubois and then Joseph Barron to Prophet's Town. [45] By this time the Prophet had had his fill of spies. As Barron stood before him, the Prophet glowered, and said, "Brouillette was here, he was a spy. Dubois was here, and he was a spy. Now you have come. You too are a spy." Then pointing to ground before him: "There is your grave, look upon it!" Fortunately, at this point Tecumseh came and reassured Barron that he would visit Vincennes in August to talk with Harrison.

However, Tecumseh's meeting with Harrison did not resolve the conflicts between the two cultures. Harrison told Tecumseh that he had bought the lands fairly, but Tecumseh called him a liar. The following year at another meeting, the results were equally bad. During this time, Harrison employed Brouillet as a scout, traveling about the remote settlements to calm the settlers, and to carry messages to the Prophet. [46] Finally, in September of 1811 Harrison decided to drive the Prophet from Prophet's Town and disperse his followers. What resulted was the Battle of Tippecanoc, fought on November 7, 1811.

Michel Brouillet was not at this battle. He was at Fort Harrison, near Terre Haute, and a few days after the action, he interviewed some of the Indians to get their account of the battle. [47]

During the ensuing War of 1812, Brouillet was busy acting as a scout and carrying messages between Fort Harrison and Vincennes. After the war, he served as Indian agent at Fort Harrison until 1819, when the Indians sold out their claims in central Indiana and moved west of the Mississippi, thus ending the fur trade in southern Indiana. After this, Brouillet settled down in Vincennes, and went into the grocery business, which seems to have mostly consisted of selling liquor.

As a kind of epilogue, in November of 1826, the remnants of the Shawnee tribe, with the Prophet and the son of Tecumseh, stopped at Vincennes on their way west. [48] They went to the tavern of Michel Brouillet at the corner of Second and Main because he could interpret their language. It is not recorded what they said. [49]

On 26 December 1838, Captain Michel Brouillet died, and the next day, as the Western Sun reported, "his remains were committed to the silent grave with military honors and accompanied by a large concourse of his fellow citizens." [50] As noted earlier, Michel Brouillet was not famous and he did not change the course of events. Nevertheless, he certainly was a participant in an important and exciting period in the history of the frontier.

NOTES

1Michel Brouillet's age is given as 45 in the Vincennes census of October 18, 1787. Continental Congress Papers, item 48, pp. 167-173. The census also lists a Francois Brouillet, age 42, probably Michel's brother, and a Louis Brouillet, age 35. Jacob P. Dunn, ed., Documents Relating to the French Settlements on the Wabash, Indiana Historical Society Publications, II, No. 11 (Indianapolis, 1894), pp. 427 and 430.

2It is identified as "Riviere a la Brouette" in Thomas Hutchin's map of 1778, based on his visit to the area in 1767-8. Literally this means "River of the Wheelbarrow," but this is probably a mistake for "Riviere a Brouette," a common spelling for Brouillet. "A New Map of the Western Parts of Virginia, Pennsylvania, Maryland and North Carolina," by Thomas Hutchins, 1778, Plate XXIX of Atlas of the Illinois Country 1670-1830, ed. Sara Jones Tucker, (Springfield, Ill.: Illinois State Museum, 1942).

3D. Barnhart and Dorothy L. Riker, Indiana to 1816; the Colonial Period, (Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society 1971), pp. 122, 164, 202n.

4Copy of May 1, 1773, Deed to Michel Brouillet from Charles Boneau, RHC #180, in Byron R. Lewis Historical Library, Vincennes University, Vincennes, Indiana.

5Records of the Parish of St. Francis Xavier, Vincennes, Indiana, Vol. I, 1749-1784, p. 20, in Lewis Library, VU.

6Barnhart and Riker, pp. 178-179, 187.

7John D. Barnhart, ed. Henry Hamilton and George Rogers Clark in the American Revolution with the Unpublished Journal of Lieut. Gov. Henry Hamilton (Crawfordsville, Indiana, 1951), p. 146.

8Letter from Winthrop Sargent to Robert Buntin, October 23, 1797, in American State Papers. Public Lands (8 vols., Washington, D.C., 1834-61), vol. I, p. 87.

9Barnhart and Riker, pp. 188-189.

10James Alton James, ed., George Rogers Clark Papers, 1771-1781 (Illinois Historical Collections), VIII, (Springfield, 1912), pp. 56-59.

11Barnhart, p. 146.

12Ibid.

13Deposition of Michel Brouillette, August 22, 1823, in records of Francis Vigo Chapter of D.A.R., Vincennes, Indiana.

14Copy of Commission from John Todd, County Lieutenant of the County of Illinois, Commonwealth of Virginia, in records of Francis Vigo Chapter, D.A.R., Vincennes.

15Orders to Captain Michel Brouillet from Major J. M. P. Legras, Post Vincennes, September 29, 1779. Copy by Mrs. Eliza McKenny Brouillet for Mary A. Brouillette, in records of Francis Vigo Chapter, D.A.R., Vincennes.

16Pioneer and Historical Collections, XIX, p. 467.

17John J. Doyle, The Catholic Church in Indiana, 1686-1814 (Indianapolis, 1976), p. 51. Records of St. Francis Xavier Church, Vincennes, vol. I, p. 80, in Lewis Library, VU.

18Deposition of Michel Brouillette, August 22, 1823.

19Western Sun and General Advertiser, February 25, 1843.

20H. C. Bradsby, History of Vigo County (Chicago, 1891), p. 125.

21Otho Winger, The Lost Sister Among the Miamis (Elgin, Ill., 1936) p. 142, lists Jean Baptiste Brouillette as born in 1796. His obituary in the Lafayette Courier, July 6, 1867, says he was born at Fort Harrison (near present-day Terre Haute), "his father was a Frenchman, and was made a captive when a youth." In The Journals and Indian Paintings of George Winter, 1837-1839 (Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society, 1948) p. 44, George Winter recollects that J. B. Brouillette was the half-brother of the Brouillette who played the fiddle for the dances in Logansport in 1837. This would have been Michel Brouillet's son Michel Bradamore Brouillett who published A Collection of Cotillions, Scotch Reels, &c. Introduced at the Dancing School of M B. Brouillett, (Logansport, Indiana, 1834,) a copy of which is in the Indiana Collection of the Indiana State Historical Library.

22Records of the Parish of St. Francis Xavier, vol. II, p. 15.

23Knox County Deed Book "A," p. 175-6, in Knox Co. Recorder's Office, Vincennes, Ind.

24Records of the Parish of St. Francis Xavier, vol. II, p. 126.

25Charles B. Lasselle, "The Old Indian Traders of Indiana," Indiana Magazine of History, vol. II, p. 7, and p. 13, f.n. 19.

26Archives, Record Group No. 75, LR - 1803 I O.I.T., Fort Wayne Factory.

27Logan Esarey, ed. Messages and Letters of William Henry Harrison (Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Commission, 1922) vol. I, pp. 102-3.

28J. Kappler, ed., Indiana Affairs, Laws and Treaties (2 vols., Washington, D.C., 1903), II, pp. 89-90.

29R. David Edmunds, The Shawnee Prophet (University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, 1983), Chapters 1-3.

30Lawrence Henry Gibson, The Moravian Indian Mission on White River, Indiana Historical Collections (1938), vol. XXII, pp. 455-7, 627-8.

31In the Lasselle Papers of the Indiana Historical Society is a list of Indians on the Mississinewa who owed money to the Lasselle fur-trading company, among them "la femme de Michel Brouillet."

32The marriage was before a Judge, probably in 1806; it was revalidated by the church on 21 September 1811, according to parish records of St. Francis Xavier Church.

33Knox County Deed Book "A," pp. 241-3.

34William Wesley Woolen et al., eds. Editorial Journal of the Indiana Territory, 1800-1816, Indiana Historical Society Publication. (1900), vol. III, p. 141.

35National Archives, RG 107, F-1808, Secretary of War, Letters Received, "Memorandum for the Committee of Friends from Baltimore," Fort Wayne, 26 May 1808.

36Edmunds, Chapter 4.

37Esarey, vol. I, pp. 346-7.

38Ibid, 349-78.

39Ibid, 395.

40Ibid, pp. 417-8

41Ibid, p. 425.

42Ibid.

43Ibid.

44The Western Sun, June 23, 1810.

45John B. Dillon, A History of Indiana (Indianapolis, 1859), pp. 449-50.

46Esarey, pp. 475-6, 480-1, 512, 537-8.

47Ibid, pp. 643-6.

48The Western Sun, December 13, 1826.

49"Recollections of Vincennes," by "Howard," The Vincennes Weekly Western Sun, January 25, 1868, p. 2.

50The Western Sun, December 29, 1838.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

1983-1984/sec7.htm

Last Updated: 23-Mar-2011