|

ACADIA

Guidebook 1940 |

|

| OPEN ALL YEAR |

|

Acadia NATIONAL PARK MAINE |

||

|

A BIT OF ROCKY SHORE LINE

| ||||

ACADIA NATIONAL PARK, occupying old French territory on the coast of Maine, was created by act of Congress in 1919 from lands donated to the Federal Government. The name commemorates the ancient French possession of the land and the part it had in the long contest to control the destinies of North America.

Surrounded by the sea, Acadia is dominated by the bold range of the Mount Desert Mountains, whose ancient uplift, worn by time and ice erosion, remains to form the largest rock-built island on our Atlantic coast, "l'Isle des Monts deserts," or Mount Desert Island.

The coast of Maine has been formed by the flooding of an old and water-worn land surface, which has turned its heights into islands and headlands, its stream courses into arms and reaches of the sea, its broader valleys into bays and gulfs. The Gulf of Maine itself is such an ancient valley, whose broken and strangely indented coast, 2,500 miles in length from Portland to St. Croix—a straight-line distance of less than 200 miles—is simply an ocean-drawn contour line marked on its once bordering upland.

At the center of this coast, the most beautiful in eastern North America, there stretches an archipelago of islands, island-sheltered waterways, and lake-like bays, and at its northern end, dominating the whole with its mountainous uplift, lies Mount Desert Island, where on the national park is located.

YOUNG BALD EAGLES

THE STORY OF MOUNT DESERT ISLAND

Mount Desert Island was discovered by Champlain in September 1604, 16 years and more before the coming of the Pilgrims to Cape Cod. He had come out the previous spring with the Sieur de Monts, a Huguenot gentleman, soldier, and governor of a Huguenot city of refuge in southwestern France, to whom Henry IV had entrusted previously the establishment of the French dominion in America. A few years later the island again appears as the site of the first French missionary colony established in America, whose speedy wrecking by an armed vessel from Virginia was the first act of overt warfare in the long struggle between France and England for the control of North America.

In 1688 private ownership began, the island being given as a feudal fief by Louis XIV to the Sieur de la Mothe Cadillac—later the founder of Detroit and Governor of Louisiana, who is recorded as then dwelling with his wife upon its eastern shore and who still signed himself in his later documents, in ancient feudal fashion, Seigneur des Monts deserts.

In 1713 Louis XIV, defeated on the battlefields of Europe, ceded all of Acadia except Cape Breton to England, and Mount Desert Island, unclaimed by Cadillac, became the property of the English Crown. Warfare followed till the capture of Quebec in 1759, when settlement from the New England coasts began. To the Province of Massachusetts was granted that portion of Acadia which now forms part of Maine, extending to the Penobscot River and including Mount Desert Island, which it shortly thereafter gave "for distinguished services" to Sir Francis Bernard, its last English governor before the Revolution. Title to it was later confirmed to him by a grant from George III.

With the outbreak of the Revolution, Bernard's stately mansion on the shore of Jamaica Pond and his far-off island on the coast of Maine were confiscated, as he took the King's side and sailed away from Boston Harbor. Thus Mount Desert Island became once more the property of Massachusetts. But after the war, when Bernard had died in England, his son, John, petitioned to have his father's ownership of the island restored to him, claiming to have been loyal himself to the colony, and a one-half undivided interest in it was given him. Then came the granddaughter of Cadillac—Marie de Cadillac—and her husband, French refugees, bringing letters from Lafayette, and in turn petitioned the General Court of Massachusetts to grant them her grandfather's possession of the island in return for the assistance which France had given in the Revolution. And the General Court, honoring their claim, gave them the other undivided half. When the surveying of the island had been completed, the western portion was in the hands of Bernard, who promptly sold it and went to England; the eastern portion, now the property of Marie de Cadillac and her husband, M. de Gregoire, was gradually sold by them, piece by piece, to settlers on the island.

During the first half of the nineteenth century, Mount Desert Island still remained remote and inaccessible, except to coasting vessels; but fishing hamlets gradually grew up along its shore, the giant pines whose slowly rotting stumps one comes upon today among the lesser trees were cut and shipped away, town government was established, roads of a rough sort were built, and the island connected with the mainland by a bridge and causeway. The coming of steam brought about a complete transformation of Mount Desert Island. The Boston & Bangor Steamship Line was established; a local steamer connected Southwest Harbor with this line, and summer life at Mount Desert began.

After the War Between the States, many people began to learn of the great beauty of Bar Harbor. Although steamers did not come until 1868, and the nearest railroad terminal was at Bangor, 50 miles away, with a rough road between, the summer population grew by leaps and bounds. Soon the native cottages and fishermen's huts were filled to overflowing, and visitors were forced to live in tents, feeding on fish and doughnuts, and the abundant lobster. The cottages expanded and became hotels, simple, bare, and rough, but always full. The life was gay and free and wholly out-of-doors—boating, climbing, picnicking, buckboarding, and sitting on the rocks. All was open to wander over or picnic on; the summer visitor possessed the island. Then lands were bought, summer homes were made, and life of a new kind began.

It was from the impulse of that early summer life that the movement for public reservations and the national park arose, springing from pleasant memories and the desire to preserve in largest measure possible the beauty and freedom of the island for the people's need in years to come.

Like all national parks, Acadia is an absolute sanctuary for wildlife, plant and animal. Land and sea, woodland, lake, and mountain—all are represented in remarkable concentration. Here, too, the flora of the Northern and Temperate Zones meet and overlap, and land climate meets sea climate, each tempering the other. Acadia lies directly in the coast migration route of birds.

The neighboring ocean provides a limitless field for biologic study, while the sea beach and tidal pools form an infinite source of interesting study.

NORTHERN HARDWOODS AND HEMLOCKS, SOUTH END OF EAGLE LAKE

THE ACADIAN FOREST

As a botanical area, Mount Desert Island is singularly rich, due to the fact that forest fires and recent human agencies have not impoverished the natural growth. Protected and cared for within the park limits, and restored when necessary, this growth will in time represent completely, as in a wild botanic garden, the entire Acadian region. Wildflowers are abundant from early spring, when the trailing arbutus, or Mayflower, puts forth its blossoms, until the witch hazel blooms in fall, scattering its seeds as it flowers.

In trees and forest growth Mount Desert Island represents the wide territory comprised in eastern and northern Maine, the Maritime Provinces, Labrador, and Newfoundland. The forest of this region, best described as the Acadian Forest, since it is in the old Acadian region that it finds its best expression, is the boreal extension of the ancient Appalachian forest of mingled coniferous and hardwood trees, ranging northward along the mountain folds from Tennessee and Georgia.

GEOLOGIC HISTORY OF MOUNT DESERT ISLAND

Mount Desert Island, on which the park is located, is a land mass that has been battered by both external and internal geologic forces for many million years. Here, a number of agencies of land building and destruction are exemplified either in action or by their products. The result of these forces, acting through the centuries, is a beautiful combination of mountain, lake, and shore.

The visitor traveling about the island is attracted at every turn by the physiographic features which have been produced in geologically recent time, the most notable being the great sea cliffs. These are produced by the ocean waves cutting and undermining, like a huge saw, the rocks which tower above their reach.

The noisy waves touch only the coast line, but the silent forces of rock disintegration also accomplish much work. The summit of Cadillac Mountain, now slowly crumbling away, still possesses in sheltered spots the smooth, polished surfaces which were produced by the glaciers as they moved over the rock. The combined attacks of frost, expansion, and contraction by sudden temperature changes, chemical disintegration, prying by plant roots, and even the solvent power of rainwater, little by little break down the solid granite. Chemical rock decay, due to the ever present barnacles, kelp, mosses, lichens, and mussels, is an example of the geologic relationship with living things. Down the mountain slopes loosened blocks are sliding, wasting, and rounding. Smaller and smaller grow the rock fragments until they are merely sand and clay, which the rain washes or the winds blow into the sea, the ultimate destination of all rock waste.

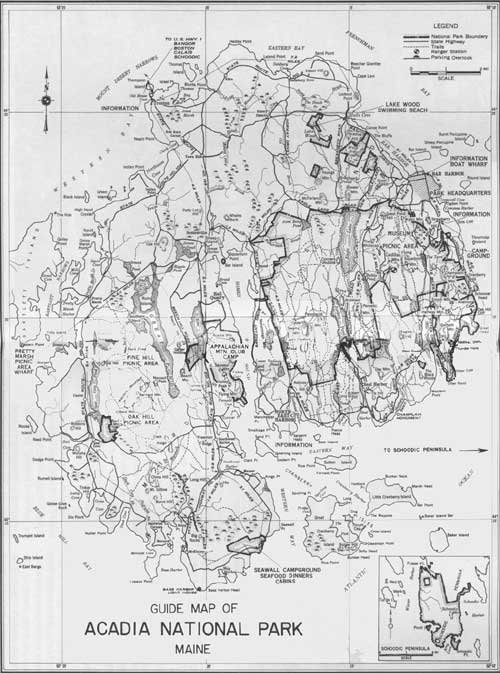

GUIDE MAP OF ACADIA NATIONAL PARK, MAINE

(click on image for a PDF version)

Recently, as measured by geologic time, an enormous ice sheet passed over the land, rounding its features and deepening and broadening its river valleys. During the early stages of its advance, the direction of flow was controlled largely by the southward trending river valleys. As the ice became thicker it covered the entire island and its direction of movement shifted more to the eastward.

While flowing southward the ice rounded all of the northern slopes, but tended to pluck out loose rock or gouge the southward facing slopes so that there was produced a surface having a notched appearance. At many places on the island there are polished, scratched, or crescent-shaped marks produced by the scouring effect of the fragments of rock and boulders held frozen in the ice.

The weight of the ice is thought to have depressed Mount Desert Island possibly as much as 300 feet. The ancient sea cliffs and beaches, some of which are now 200 feet above sea level, are evidence of this action. As the ice melted away, the land rose slowly, but not to its former level. This is shown by the present drowned mouths of the river valleys.

Thus we may summarize the geologic history of Mount Desert Island as two periods of deposition, each terminated by mountain-building forces and each subsequently reduced by erosion almost to a plane. The final uplift initiated a new cycle of erosion and permitted the sea to cut the rocky cliffs which are now its greatest scenic asset.

LOOKING NORTH TO SAND BEACH FROM OCEAN DRIVE

SCHOODIC POINT

Several years ago the bounds of Acadia National Park were extended to include Schoodic Point, enclosing the entrance to Frenchman Bay upon the eastern side as Mount Desert Island does upon the western. It was a splendid acquisition, obtained through generous gifts and made possible of acceptance by an act of Congress.

Schoodic Point juts further into the open sea than any other point of rock on our eastern coast. On it the waves break grandly as the ground swells come rolling in after a storm at sea. Back of the ultimate extension of the Point a magnificent rock headland rises to over 400 feet in height—commanding an unbroken view eastward to the entrance of the Bay of Fundy, southward over the open ocean, and westward across the entrance of Frenchman Bay to the Mount Desert Mountains in Acadia National Park. It is a view unsurpassed in beauty and interest on any seacoast in the world.

A park road branching from Maine's coastal highway to New Brunswick follows the rock-bound shore of Schoodic Peninsula to its surf-beaten extremity upon Moose Island, thence along the eastern shore of the Peninsula to Wonsqueak Harbor. There it connects again with the coastal highway, making a magnificent detour for motorists on their way to our national boundary and the Maritime Provinces of Canada.

HOW TO REACH THE PARK

Acadia National Park may be reached by railroad, bus, or automobile.

The railroad terminus for the park and Mount Desert Island resorts is Ellsworth, Maine, on the line of the Maine Central Railroad. Comfortable motor busses transport rail passengers from Ellsworth to Bar Harbor, Seal Harbor, Northeast Harbor, and Southwest Harbor. Information regarding rail connections between principal eastern cities and Ellsworth can be had on application at any railroad ticket office.

The park may be reached by bus from the north, via the Maine Central Transportation Co., from Bangor and Ellsworth, which are served by Eastern Greyhound Lines of New England. Complete information on schedules and rates may be obtained from any bus agent in the United States or Canada.

By motor the park is accessible from all eastern points over good State highways. The island is connected with the mainland by a steel-and-concrete bridge.

Scheduled airplane service from all points in the United States to Bangor is available by Boston & Maine Airways from Boston during the summer.

INFORMATION

The office of Acadia National Park is situated in Bar Harbor, Maine, at the corner of Main Street and Park Road. It is open daily, except Sundays, from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. Correspondence relating to the park should be sent to Superintendent George B. Dorr at that address.

At all villages on the island are booths where information concerning train and bus service, motor routes, fares, hotels, rooming houses, and eating places may be obtained. A similar booth is maintained jointly by the several island towns at the junction of State Routes 3 and 198, where motor traffic first enters Mount Desert Island. Maps of Mount Desert Island and literature relating to Acadia National Park may be obtained from the park office or the information booths.

VISITORS VIEW THUNDER HOLE Rinehart photo

NATURE GUIDE SERVICE

Free nature guide service is available to the visitor in Acadia. The park naturalist and his staff conduct a program designed to acquaint the visitor with the geology, plant and animal life, and his tory of the area.

Each day there is a different feature on the program. Nature walks, strenuous hikes, sea cruises around Frenchman Bay, and trips to the museum on Little Cranberry Island, are included among the activities.

The campfire programs at the public campground three nights each week are of great interest. Impromptu entertainment by the campers themselves, group singing, and lectures illustrated by slides and movies comprise the programs.

The auto caravans, where the visitors drive their own cars, guided by the naturalist, are of interest. Stops are made at the Thunder Hole, Otter Cliff, Champlain Monument, Asticou Terraces, Somes Sound, and Cadillac Mountain.

Printed programs of this free service are available at all information booths on the island as well as at the park office, the public campground, the office of the naturalist, and at the leading hotels.

MUSEUMS

An archeological museum, dedicated to public use, has been built on land adjoining the Sieur de Monts Spring entrance to the park. It contains relics of the stone-age period of Indian culture in this region, as well as books and maps.

Another interesting museum is located at Islesford on Little Cranberry Island. Here is found a unique collection of prints and documents relating to the settlement and early history of the region. This museum is reached by a half-hour motorboat trip from Seal Harbor, Northeast Harbor, or Southwest Harbor.

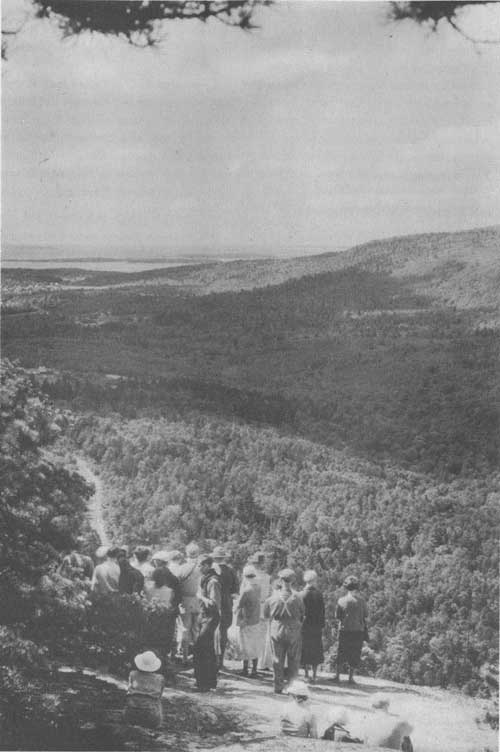

NATURE GUIDE PARTY LOOKING OVER BAKER ISLAND AND THE OCEAN

FREE PUBLIC CAMPGROUND

A campground is maintained by the National Park Service for motorists bringing their own camping outfits. It is equipped with running water, modern sanitary conveniences, outdoor fireplaces, electric lights, and facilities for washing clothes. Camping is limited to 30 days.

ROADS AND BRIDLE PATHS

A road of great beauty through the lake district connects Bar Harbor with Seal Harbor, Northeast Harbor, and southern shore resorts. Rising from this, another road leads to the summit of Cadillac Mountain, the highest point on our eastern coast. Entrance to these roads is equally convenient from Bar Harbor or Seal Harbor. On Schoodic Peninsula a shore line drive follows closely the rugged coast. State Highway No. 186 may be left at Winter Harbor and reentered at Birch Harbor.

In addition to the park roads, there are more than 200 miles of State and town roads encircling and traversing Mount Desert Island. Reaching every point of interest, they exhibit a combination of seashore and inland scenery not found elsewhere on the eastern coast.

For those who do not have their own automobiles, there are cars for public hire in the various villages adjacent to the park.

Connected with the town road system and leading into and through the park is an excellent system of some 50 miles of roads for use with horses. Stables at Eagle Lake, Jordan Pond, and Northeast Harbor furnish saddle and driving horses for trips over these roads.

TRAILS AND FOOTPATHS

There are at present some 150 miles of trails and footpaths in the park, reaching every mountain summit and traversing every valley. Broad lowland paths offer delightfully easy walks; winding trails to the mountain summits are provided for those preferring a moderately strenuous climb; and rough mountain side trails give opportunity for hardy exercise to those who enjoy real hiking. It is only by means of these trails that the park can really be seen and appreciated; the system is so laid out that there is no danger of becoming lost.

ACCOMMODATIONS OUTSIDE THE PARK

In the various villages on Mount Desert Island excellent accommodations for visitors are to be had at reasonable rates. The National Park Service exercises no control over these accommodations, which range from high-class summer hotels to good rooming houses and restaurants. Information concerning these facilities may be secured by addressing:

Publicity Office, Bar Harbor, Maine; Publicity Office, Northeast Harbor, Maine; Publicity Office, Southwest Harbor, Maine.

PARKING AREA ON TOP OF CADILLAC MOUNTAIN

RULES AND REGULATIONS

FIRES.—No fires shall be kindled without first obtaining permission from the superintendent or his representatives. They must be completely extinguished before leaving. The use of fire crackers or fireworks is prohibited except by written permission.

CAMPS.—No camping permitted except within the regular campgrounds. Camping is limited to thirty days.

TREES, FLOWERS, AND ANIMALS.—Trees and shrubs must not be cut or broken. Flowers must not be picked. Birds and animals must not be molested. The injury or defacement of any natural feature is prohibited.

REFUSE.—Do not throw paper, lunch refuse, or other trash on the roads, trails, or elsewhere. Deposit all such debris in the receptacles provided for the purpose.

ADVERTISEMENTS.—Private notices or advertisements shall not be posted or displayed in the park.

AUTOMOBILES.—Drive carefully at all times. Obey the park speed limit and other automobile regulations.

DISORDERLY CONDUCT.—Persons who render themselves obnoxious by disorderly conduct or bad behavior are subject to penalties, and may be summarily removed from the park.

ACCIDENTS.—Accidents of whatever nature shall be reported as soon as possible to the superintendent or at the nearest ranger station.

SALE OF ARTICLES.—No person, except those who are especially authorized to do so, shall offer for sale any articles or commodities. The soliciting of contributions by any method is prohibited.

GULLS ARE NUMEROUS ALONG THE PARK'S ROCKY COAST

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> |

1940/acad/sec1.htm

Last Updated: 20-Jun-2010