|

LASSEN VOLCANIC

Circular of General Information 1936 |

|

LASSEN VOLCANIC

National Park

• SEASON FROM JUNE 1 TO SEPTEMBER 30 •

LASSEN VOLCANIC NATIONAL PARK, in northeastern California, was created by act of Congress approved August 9, 1916, to preserve Lassen Peak and the area containing spectacular volcanic exhibits which surrounds it. This impressive peak, from which the park derives its name, stands near the southern end of the Cascade Mountains and is the only recently active volcano in continental United States. Its last eruptions, occuring between 1914 and 1917, aroused popular and scientific interest in the area.

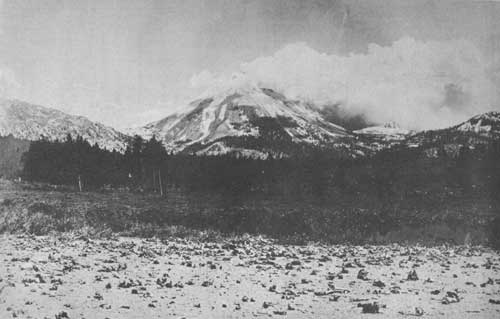

The last vigorous activity of Lassen Peak in 1915. Loomis photo.

GEOLOGIC HISTORY1

1Abstracted from Geology of Lassen Volcanic National Park, by Howel Williams

The Cascades are volcanic in origin and are dotted with numerous inactive volcanic peaks or craters, the most noted being Mount Rainier, Mount Baker, Mount Adams, Mount Hood, Mount Saint Helens, Mount Jefferson, Mount Shasta, the Three Sisters, and Crater Lake. Twenty-five miles south of the park this range meets abruptly the northern end of the Sierra Nevada, which is a great tilted block of the earth's crust, with lofty summits near its eastern border and long westward slopes dipping gently into the Central Valley of California.

The Cascade Range is not ancient measured in geologic time. Its beginning dates back about 2 million years, into the geologic period known as the Pliocene, about a million years before the great Ice Age, or Glacial Period. The character and arrangement of the older rocks indicate that earlier mountains, long before worn down, had occupied the region. The present range rests upon a great platform of lava flows, which issued from many vents and fissures. These lavas accumulated, flow upon flow, to depths of several thousand feet over wide areas in Washington, Oregon, southern Idaho, and northern California. Later this platform was bent, or arched, slightly upward along the line of the Cascades. No more widespread floods of lava came forth, but numerous localized eruptions produced the magnificent series of peaks which are now snowcapped and for which the Cascades are famous. Old sediments deposited in ancient seas in adjacent regions, indicate that the Lassen area was probably at one time covered by an arm of the sea and that the volcanic formations which now cover it are underlain by much older strata, late Mesozoic or Tertiary in age.

Throughout the volcanic history of the Cascade region long intervals of quiescence have separated the periods of intermittent activity. During the active periods both explosive eruptions and quiet flows of lava were common. Cinder cones, widespread beds of fragmental material such as tuffs, and the so-called ash beds, are explosion products. Flows produced lava fields and broad, gently sloping volcanoes. At many places both types of eruption have issued at different times from the same vent; in this manner most of the great volcanoes have been built.

At Lassen Peak the activity has been so recent that there has been very little time for the modification of its volcanic features by erosion. The greatest modifying agent has been glaciation, but even its effects are concealed in part where volcanic activity has continued after the close of the Glacial Period.

Lassen Peak. Holmes photo.

LASSEN PEAK AND VICINITY

The western part of the park includes a profusion of volcanic peaks of the "dome" type, of which Lassen Peak itself is the outstanding example. Others include White Mountain, Chaos Crags, Eagle Peak, and Bumpas Mountain, all closely related in origin. They represent a northward stepping succession of outlet vents from the same parent lava reservoir which formerly found outlet through the earlier and greater volcano of Mount Tehama, of which only relics are now found in Brokeoff Mountain, Mount Diller, Black Butte, and Diamond Peak.

The great cone of Lassen Peak, rising 10,453 feet above sea level, on the north slope of an ancestral mountain, is almost completely wrapped in a smooth-sloping mantle of rock fragments, broken from its own cliffs. Lassen differs from the "strato-volcanoes", the most common type, which are built up of alternate beds of lava and fragmental material, sloping away steeply from a central crater. The mountain as it stands today has passed through two stages of growth. The earlier Lassen was a broad, gently sloping volcano of the "shield" type, built of lava beds, like the volcanoes of the Hawaiian Islands and like the neighboring Raker and Prospect Peaks, Red Mountain, and Mount Harkness. It rose by a succession of lava flows to an elevation above 8,500 feet, with a base 5 miles across from north to south and 7 miles from east to west. In the second stage the steep Lassen cone was built on this broad, substantial platform. This, the more conspicuous portion, represents a still rarer "dome" type of volcano, formed by stiff, viscous lava which was pushed up through the vent, like thick paste squeezed from a tube. Piling up in and around the old crater, this stiff lava rose in a bulging dome-like form high above it.

Movements due to the rise of lava into the upswelling mass, the pressure of steam and gases imprisoned within it, and the chill of the outer portions on exposure to the air caused a continuous breaking away of huge blocks and slabs of rock accompanied by many smaller fragments. These accumulated about the rising dome while the mountain was still growing and formed great rock slides on its slopes, much as they appear today. This rock mantle (talus) in places reaches almost to the summit and caps the bulging dome in the form of a cone.

The large boiling pool near the east end of Bumpas Hell. Grant photo.

Compared with the slow upbuilding of the more common type of volcano, the rate of growth of an upswelling dome is phenominally rapid, as witnessed by the history of Santa Maria, in Guatemala, and Mont Pelee, in the Island of Martinique. By comparison with the growth of these two domes it has been estimated that the steep cone of Lassen Peak may have been thrust up in the surprisingly short period of 5 years.

Most dome volcanoes have no crater at the top, but at Lassen Peak, gases escaping from lavas deep below maintain open conduits through the softer, central part of the cone. The violence of their discharge at times shoots forth lava in dustlike form, producing the so-called volcanic "ash" of the tuff beds and "mud" flows. Such activity opens a funnel-shaped or cuplike crater at the top. Before the eruptions of 1914-17 the crater of Lassen Peak was an oval bowl approximately 1,000 feet across and 360 feet deep.

Following the rapid rise of the Lassen Dome, there was a long period of quiescence. Nevertheless, prior to the activity of 1914-17 one or more "mud" flows had swept down the northeastern slope, probably within the past 500 years, as judged from the state of preservation of logs that were buried in the lava and recently have been uncovered along the course of Lost Creek.

On May 30, 1914, a series of eruptions began which lasted through June 1917, the most recent volcanic activity in continental United States. Unfortunately, during this period no scientific observer was stationed in the region to record and report the detailed account of events. The story has been pieced together from fragmentary reports of occasional witnesses and by inferences from the study of the remaining evidences of the activity.

The first eruption, which was short and mild, opened a new vent within the old crater. Water from melting snow, trickled down through crevices deep into the volcano and there was converted into steam. This may have aided or served to start the action, which was due primarily to rising heat within. The materials thrown out during the first year were not hot; in fact, most of them were too cold to melt the snow upon which they fell. By March 1915 more than 150 explosions had occurred, most of them mild. The coarser materials fell on the slopes of the peak, but the finer dust was spread over a much larger area, mostly toward the northeast; due to the prevailing winds, some fell as far as 15 miles to the south.

Another violent eruption occurred in May 1915, possibly set off by the melting of the exceptionally heavy snow which had accumulated during the preceding winter. On May 19 the first glowing lava made its appearance, rising in the new crater and spilling through the western notch in the crater rim in the form of a tongue which reached down the slope 1,000 feet. During the night of May 19 the snow was melted on the northeastern slope, causing destructive flows of mud which swept boulders up to 20 tons in weight 5 to 6 miles into the valleys of Hat Creek and Lost Creek.

Three days later, on May 22, another and lesser mud flow moved down the same slope, and minor flows took place on the north and west flanks of the volcano. At the same time a terrific hot blast, heavily charged with dust and rock fragments, was discharged down the northeast flank of the peak. So violent was this outburst that trees on the slopes of Raker Peak, more than 3 miles away, were felled uniformly in the direction of the on-rushing blast. At the same time a vertical column of smoke and ash rose more than 5 miles above Lassen crater.

The energy of the volcano was largely spent by the end of the 1915 eruption. With only occasional outbursts of steam and ash, the activity definitely subsided during the next 2 years. A final series of violent explosions occurred in May and June 1917, again following the melting of considerable quantities of snow. The activity of 1916 and 1917 produced little effect besides modifying the form of the crater by opening new vents within it. Most of the crater is now filled by the rough, blocky lava which rose into it in May 1915; but at the northwest a yawning chasm through the crater wall was opened by later explosive eruptions. In view of the volcanic history of the region, renewed activity at Lassen is not probable for many years, although there is no reason to suppose that the volcano is yet extinct.

Steam vents and boiling pools in Bumpas Hell. Holmes photo.

OTHER DOME VOLCANOES NEAR LASSEN PEAK

Almost surrounding Lassen Peak on three sides, north, east, and south, are several other peaks which are similar to Lassen in their dome type of origin, although Lassen is the only one which has a crater in the top of its dome plug. The more common type of dome, without a crater at the top, is represented by White Mountain, Chaos Crags, Eagle Peak, Vulcans Castle, Mount Helen, Bumpas Mountain, and the hills north of Chaos Crags. With the exception of these hills, the domes named appear to be progressively younger from south to north. Those at the south, between Lassen and the old Tehama Volcano, are preglacial in age, or were thrust up early in the Glacial Period. However, the lava forming the broad foundation of the Lassen dome is older than these domes.

CHAOS CRAGS AND CHAOS JUMBLES

Chaos Crags and Chaos Jumbles present the most spectacular scene of turbulent disorder to be found in the entire region. No words can convey an adequate picture of the piles of huge angular blocks, thrown together in wild confusion over the surface of these domes, or of the bristling pinnacles and stacks that project above them. Enormous banks of angular talus, many of them more than 1,000 feet high, encircle the domes, merging at the northwest into the choppy disarray of the Jumbles.

The activity at Chaos Crags, like that of many volcanic domes the world over, was divided into three phases: First, explosive eruptions building a series of cinder cones, then the thrusting up of the molten viscous lava as steep-sided domes, and lastly the partial destruction of these domes by renewed explosions—all only about 200 years ago.

The early violent eruptions formed several cinder cones at the north base of Lassen Peak. A portion of one of these cones, with its crater 600 feet in diameter and 60 feet deep, is still preserved against the south flank of the Crags, and the disorganized remains of at least two others are recognizable. The pushing up of the viscous lava doubtless followed soon afterward, forming two domes, each about a mile in diameter, the older south dome partially encircling the later and higher north dome. Unable to flow for more than a short distance, this stiff lava piled up about the vents. Great strains were set up in the solidifying mass by the upward surge of the lava into the swelling dome and probably by frequent violent explosions of steam and gases from various parts of the stiffening mass. Thus vast talus slopes were formed by the breaking and crumbling of the rising masses, and the domes were thrust up through their own accumulating debris, as the famous "spine" of Mont Pelee.

Lake Helen. In the distance are Brokeoff, Diller, and Pilot Pinnacle Mountains.

The north dome had risen 1,800 feet above the surrounding country when explosions at the base of the rising mass blasted away the support from the north face and hurled vast quantities of broken and falling lava out upon the cinder-covered region below. This rock blast was shot forward with such momentum that its front rushed 400 feet up the opposite slope of Table Mountain, 2 miles distant from the craters at the north foot of the Crags, and stopped there with an abrupt front. An area 2-1/2 square miles in extent was thickly covered by angular rock, mingled with finer, sandlike material. Manzanita Lake was formed where the Jumbles obstruct Manzanita Creek. The neighboring Reflection Lake is but the largest of many pools that occupy depressions in the Jumbles.

Three miles southwest of Lassen Peak once stood a great mountain, with a base more than 12 miles in diameter and rising approximately 4,000 feet above the steaming vents and boiling springs of Sulphur Works. This mountain was built by a long succession of quiet lava flows, producing a sloping cone of the "shield" type, similar to the volcanoes of the Hawaiian Islands. After this activity ceased, the crater and the upper parts of the volcano collapsed and sank into the lavas beneath, thus forming a great bowl, or caldera, with a jagged rim. Brokeoff Mountain, with an elevation of 9,232 feet, is the largest remnant of this old rim. Other remnants are Mount Diller and Black Butte.

The beginning of this ancient mountain dates back a million and a half years to the late Pliocene Period. Before the Ice Age its great eruptions had ceased and the broad basin of the caldera was formed. Numerous steam and hot gas vents (fumaroles) and hot springs in the old caldera, including Sulphur Works, Bumpas Hell, and Steamboat Springs, show that the lava beneath the surface has not yet entirely cooled. Farther east similar types of activity may be seen at Cold Boiling Springs Lake, Devils Kitchen, Boiling Springs Lake and Terminal (Opal) Geyser. These fumaroles are of the type known as solfataras, because of the sulphur content of the gases. They decompose the lavas with which they come in contact and change them into soft olive green, yellow, or red earthy material, or into a white claylike substance. The vents are characterized by escaping vapors (mostly steam), thermal springs, and churning mud pots of various colors. Their activity is most striking in the early or late hours of the day, when the colder air causes rapid condensation of the steam into visible cloudlike masses.

VOLCANOES OF THE CENTRAL PLATEAU

Four prominent volcanoes in the landscape eastward from Lassen Peak are Raker and Prospect Peaks, Red Mountain, and Mount Harkness. They belong to the "shield" type and were built up during the Glacial Period, about the same time as the steep cone of Lassen Peak, by a sequence of numerous quiet flows of lava, like the broad base of Lassen itself.

CINDER CONE AND THE EASTERN RANGE

One of the most beautiful and unusual features of the park is Cinder Cone, 10 miles east-northeast from Lassen Peak, with its rugged and fantastic lava beds and its multicolored explosion products. The almost total absence of vegetation intensifies the appearance that the eruption occurred not long ago. Actually its last lava flow is not much older than the recent activity of Lassen itself, dating back only to the winter of 1850-51. The beginning of its history was considerably earlier, although it is entirely post-glacial and hence very recent in the geologic sense.

After most of the present cone had been piled up by explosive cinder eruptions, lava flowed out from its base; then followed a second series of cinder eruptions and also a second series of lava flows. Their magnetic properties indicate that the two earliest flows appeared about the first half of the sixth century A. D. The last of the second series was erupted in 1851, when flaring lights which persisted for many nights, were observed from various distant points. Later examination has shown that this activity produced the prominent black lava stream which emerged from the southern base of the cone, curved to the south, then east and northeast, and flowed into Butte Lake. An earlier flow of this late series separates Butte and Snag Lakes, which may formerly have been connected as one large lake.

All eruptions from the crater of Cinder Cone have been of the cinder-producing explosive type, that have pushed their way through the loose cinders at or near the base of the cone.

Some lava flows can be dated with a fair degree of accuracy by estimating the age of trees that are growing upon them. The flow which now separates Butte and Snag Lakes and which preceded that of 1851, is thought to be about 200 years old. The eastern Ridges, including the prominent Bonte Peak and Mount Hoffman, embody some of the oldest lavas of the park; hence their original volcanic features have been modified not only by glacial action but also by the pre-glacial erosion of streams.

GLACIATION

During the Glacial Period parts of the valleys and much of the Central Plateau were under a thick, slowly moving cover of ice and are now mantled by a thick blanket of glacial drift. Such material is seen in great abundance at Badger Flat, Corral Meadow, and about the shores of Snag and Juniper Lakes. Few mountain peaks rose above the ice at the time of its maximum thickness, although over most of the area this was probably less than 1,000 feet. Warner Valley, just south of the park boundary, was filled with ice to a depth of 1,600 feet.

The dominating peaks of Lassen and White Mountain and most of their neighbors, Raker Peak, Red Mountain, Prospect Peak, and Mount Harkness rose well above the general level of the ice sheet, and each of them became an ice-clad center of local glaciation, with ice moving radially down their slopes to join the general ice sheet below. At their sources on the higher peaks the local mountain glaciers were thin and their erosive powers were relatively feeble. Over broad areas where the slopes were not so steep, the ice was thicker and the scouring action on the underlying surface was vigorous, despite the slower movement.

Some of the glacial debris is arranged in well-defined ridges, elongated by the overriding ice in the direction of the movement. In the heavily glaciated Central Plateau, where the bedrock is not covered, it is commonly striated also in the direction of movement, and many of the surfaces are polished by glacial scour.

OTHER INTERESTING FEATURES

Impressive canyons, scored deeply into the ancient lavas in the westerly and southerly regions of the park, add to its attractions. Primeval forests cover the entire area, except where the loftier peaks rear their summits above timberline. In the main we find ponderosa pine, Jeffrey pine, sugar pine, lodgepole pine, incense cedar, white fir, Douglas fir, red fir, western white pine, an occasional juniper, and at the timberline the rich, dark masses of western black hemlock interspersed with occasional groups of white-bark pine. During the warm summer months a variety of flowers further enrich the profusion of color found here.

Through the forest curtain the silvery sheen and shimmer of innumerable alpine lakes greet the eye. The splendid Chain-of-Lakes in the eastern region of the park extends from Juniper, with a shore line of 5 or 6 miles at the northerly base of Mount Harkness to the northward, including Horseshoe Lake, which divides its waters between the Feather and the Pit, to flow apart for several hundred miles and meet again; then linking in Snag Lake with its broad breaches of volcanic sand formed by the ejecta from Cinder Cone; and on to Butte Lake near the eastern base of Prospect Peak with its rugged shores of lava and its scenic setting. Through the clear waters of Snag Lake, and at many places above the surface of the water, can be seen standing the remains of trees that grew at the south end of the lake before it was dammed by the lava flow and raised to its present shore level.

At a point 1.3 miles from the Lassen Peak Loop Highway are the beautiful Kings Creek Falls. The trail starts at Kings Creek Meadows at the lower crossing of the highway. By following down the left-hand side of the creek both the cascades and the falls can be seen.

A most inspiring view may be obtained from the summit of Lassen Peak. For a radius of 150 miles the magnificent panorama unfolds. To the west and southwest the Sacramento Valley spreads, like a great map, from the base of Shasta to where it merges into the great Central Valley of California, a sweep of fully 200 miles; to the north Mount Shasta looms in splendid majesty, and far beyond the peaks of southern Oregon link Lassen Volcanic with its sister park at Crater Lake; to the eastward the Susan River drainage guides the eye to Honey Lake Valley and the distant mountains of Nevada; to the south the view is over the High Sierra, across the broad expanse of forested mountain region in the Feather River country, until the picture dissolves in the purple mysteries which veil the distances.

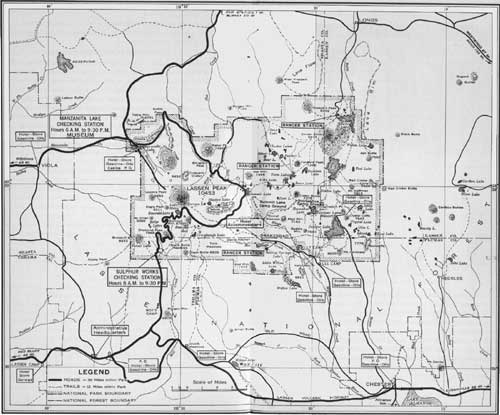

LASSEN VOLCANIC NATIONAL PARK AND VICINITY

(click on image for a PDF version)

In the foreground of the picture the splendid mountains viewed from the lower elevations now seem pigmies. At the base of Lassen to the north the Chaos Crags and to the east White Mountains stand out in bold relief. Curving from the southerly base the serrated edges of the ancient crater rim, with Lake Helen, a gemlike setting in its crescent, include six peaks which attain a height of over 9,000 feet above sea level. Brokeoff Mountain and Mount Diller stand out prominently among the encircling peaks which form the amphitheater marking the location of the once dominating volcano of the region. Compared with this ancient mountain our Lassen Peak is very recent.

Early fall skiing on the shores of Lake Helen. Holmes photo.

WILDLIFE

Lassen Volcanic National Park, like all the other national parks, is an absolute game sanctuary. Before active administration of the park began, hunting in certain sections was carried on excessively, and consequently wild game was seldom seen in any quantity. Under the protection afforded during the past few years, the park has apparently succeeded in establishing itself as a sanctuary for wild animals, which are now more numerous than before. Blacktail and mule deer may be seen in most any section of the park, and a variety of smaller animals affords much pleasure to visitors. Occasionally a black bear appears.

A ranger's pet. Holmes photo.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

1936/lavo/sec2.htm

Last Updated: 20-Jun-2010