|

MOUNT RAINIER

Circular of General Information 1936 |

|

MOUNT RAINIER

National Park

• OPEN ALL YEAR •

"OF ALL the fire mountains which, like beacons, once blazed along the Pacific Coast, Mount Rainier is the noblest", wrote John Muir.

"The mountain that was 'God'", declares the title of John M. Williams' book, thus citing the Indian nature worship which attributed to this superlative peak a dominating influence over the lives and fortunes of the aborigines.

"Easily king of all is Mount Rainier" wrote F. E. Matthes, of the United States Geological Survey, reviewing that series of huge extinct volcanoes towering high above the skyline of the Cascade Range.

"Almost 250 feet higher than Mount Shasta, its nearest rival in grandeur and in mass, it is overwhelmingly impressive both by the vastness of its glacial mantle and by the striking sculpture of its cliffs. The total area of its glaciers amounts to approximately 48 square miles, an expanse of ice far exceeding that of any other single peak in the United States. Many of its individual ice streams are between 4 and 6 miles long and vie in magnitude and in splendor with the most boasted glaciers of the Alps. Cascading from the summit in all directions, they radiate like the arms of a great starfish."

Mount Rainier in Winter Garb

Mount Rainier was named by Capt. George Vancouver, famous English navigator and explorer, on May 8, 1792, while on a geographic expedition to the northwest coast of America. His first view of the mountain, effectively described in his journal, so impressed Captain Vancouver that he wished to distinguish the mountain by giving it the honored name of Rainier after Admiral Peter Rainier who had rendered England such distinguished service during the American Revolution.

The Mount Rainier National Park, containing 377.78 square miles (241,782 acres) is a heavily forested area surrounding the great peak from which it takes its name. It was given park status by act of Congress, March 2, 1899. Fifty-three and one-tenth square miles (34,000 acres) were added when the eastern boundary was extended to the summit of the Cascades by act of Congress, January 31, 1931.

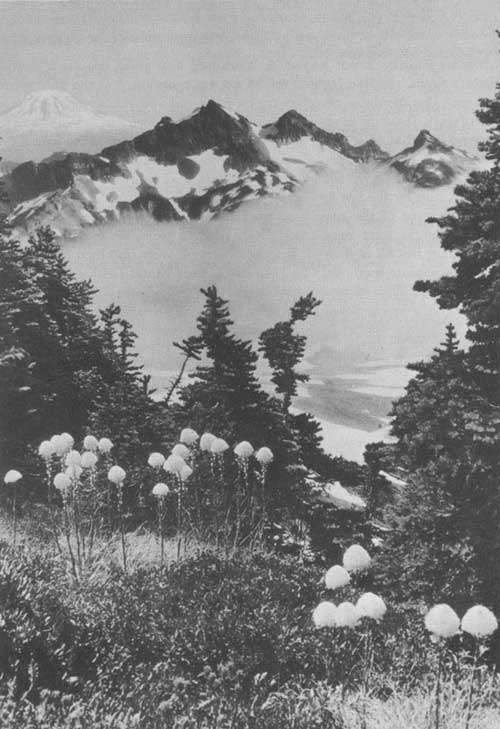

Tatoosh Range from Timberline Ridge. Mount Adams in background.

Rainier National Park Co. photo.

VAST SIZE OF MOUNTAIN

Seen from Tacoma or Seattle, Mount Rainier appears to rise directly from sea level, so insignificant seem the ridges about its base. Yet these ridges themselves are of no mean height. They rise 3,000 to 4,000 feet above the valleys that cut through them, and their crests average 6,000 feet in altitude. Thus, at the southwest entrance of the park in the Nisqually Valley, the elevation, as determined by accurate measurement, is 2,003 feet, while Mount Wow (Goat Mountain), immediately to the north, rises to an altitude of 6,030 feet.

So colossal are the proportions of the great volcano that it dwarfs even mountains of this size and gives them the appearance of mere foothills. It is the third highest mountain in continental United States, being exceeded only by Mount Whitney (Calif.), elevation 14,496 feet; and Mount Elbert (Colo.), elevation 14,420 feet.

Mount Rainier, 14,408 feet, stands approximately 11,000 feet above its immediate base, and covers 100 square miles of territory, approximately one-fourth of the area of Mount Rainier National Park.

In shape it is not a simple cone tapering to a slender-pointed summit like Fujiyama, the great volcano of Japan. It is rather a broadly truncated mass resembling an enormous tree stump with spreading base and irregularly broken top.

Its life history has been a varied one. Like all volcanoes, Rainier has built up its cone with the materials ejected by its own eruptions—with cinders and steam-shredded particles and lumps of lava and with occasional flows of liquid lava that have solidified into layers of hard basaltic rock. At one time it may have attained an altitude of not less than 16,000 feet, if one may judge by the steep inclination of the lava and cinder layers visible in its flanks. Then, it is thought, a great explosion followed that destroyed the top part of the mountain and reduced its height by some 2,000 feet. A vast crater was formed, surrounded by a jagged rim. Within this crater, which measured nearly 3 miles across from north to south, two small cinder cones were later built up, and these contiguous cones together now form the dome that constitutes the main summit of the peak. They rise only about 300 feet above the higher portions of the old crater rim, which themselves stand out as subsidiary peaks. Most prominent among these are Point Success (14,150 feet) on the southwest side, and Liberty Cap (14,112 feet) on the northwest side.

ITS LOFTY HEIGHT

Mount Rainier is not known to have had any great eruptions during historic times. Indian legends tell of a great eruption, but the date is unknown. During the nineteenth century the old volcano appears to have been feebly active at long intervals, and now it is dormant. Visitors need have no fear that an eruption will take place while they are at the foot of the mountain. That considerable heat still remains in the volcanic reservoirs below, however, is shown by the steam jets that continue to issue at the summit, and by the hot springs at Longmire.

The altitude of the main summit had for many years been in doubt. Several figures were announced from time to time, no two of them in agreement; but all of these, it is to be observed, were obtained by more or less approximate methods. In 1913 the United States Geological Survey, in connection with its topographic surveys of the Mount Rainier National Park, made a new series of measurements by triangulation methods at close range. These give the peak an elevation of 14,408 feet, thus placing it near the top of the list of high summits of the United States. This last figure, it should be added, is not likely to be in error by more than a foot or two, and may with some confidence be regarded as final. Greater exactness of determination is scarcely practicable in the case of Mount Rainier, as its highest summit consists actually of a mound of snow, the height of which naturally varies.

This crowning snow mound, once supposed to be the highest point in the United States, still bears the proud name of Columbia Crest. It is essentially a huge snowdrift or snow dune heaped up by furious westerly winds.

Skiers enjoying the broad open terrain in Paradise Valley.

Rainier National Park Co. photo.

A GLACIAL OCTOPUS

Mount Rainier bears a greater number of glaciers than any other peak in the continental United States. A study of the map will show a snow covered summit with great arms of ice extending from it down the mountain sides, to end in rivers far below. Six great glaciers appear to originate at the very summit. They are the Nisqually, the Ingraham, the Emmons, the Winthrop, the Tahoma, and the Kautz Glaciers. But many of great size and impressiveness are born of snows in rock pockets or cirques, ice-sculptured bowls of great dimensions and ever-increasing depth, from which they merge into the glistening armor of the huge volcano. The most notable of these are the Cowlitz, the Fryingpan, the Carbon, the Russell, the North and South Mowich, and the Puyallup.

The main glaciers range from 4 to 6 miles in length. They are comparable in magnitude and in scenic beauty to the glaciers of the Swiss Alps, among which only one, the Aletsch Glacier, is of decidedly superior size. The total extent of the glacial mantle of Mount Rainier is somewhat more than 40 square miles.

The ice in the glaciers is constantly, though very slowly, moving down the sides of the peak. Actual measurements on the Nisqually Glacier show that the maximum rate, in summer, is about 18 inches a day. In their upper courses the glaciers are replenished every winter by vast quantities of snow. In their lower courses they lose more substance by melting than they gain by new snowfalls. At the present time, owing to the warmth of the summer months, all the glaciers are melting back—that is, they are growing shorter at a perceptible rate. The Nisqually, which has been measured by the National Park Service annually since 1918, is melting back on an average of 70 feet per year.

WEALTH OF GORGEOUS FLOWERS

In glowing contrast to this marvelous spectacle of ice are the gardens of wild flowers surrounding the glaciers. These flowery spots are called parks. One will find Spray Park, Klapatche Park, Indian Henrys Hunting Ground, and Paradise on the map of the park, and there are many others.

"Above the forests", writes John Muir, "there is a zone of the loveliest flowers, 50 miles in circuit and nearly 2 miles wide, so closely planted and luxurious that it seems as if nature, glad to make an open space between woods so dense and ice so deep, were economizing the precious ground and trying to see how many of her darlings she can get together in one mountain wreath—daisies, anemones, columbine, erythroniums, larkspurs, etc., among which we wade knee deep and waist deep, the bright corollas in myriads touching petal to petal. Altogether this is the richest subalpine garden I have ever found, a perfect flower elysium."

The flowering plants in the forest in the zone ranging from 2,000 to 4,000 feet are those adapted to grow in the shade. Many of these live on decayed vegetation instead of preparing their own food as ordinary plants do under the action of light on the green coloring matter in their leaves. These are known as saprophytes. Two forms of the ghost plant or Indianpipe are good examples of these colorless forms. In addition to these saprophytic plants, there are many others providing their own living, such as the pipsissewa and the pyrolas, producing beautiful waxy flowers. Nearly everywhere through the moss grows the little bunchberry or Canada dogwood. Close companions of the latter are the forest anemone, the fragrant twinflower, trillium, and the beautiful white, one-flowered clintonia. The swordfern, deerfern, oakfern, lady fern, and woodfern all vie with each other in producing a beautiful setting among the giant trees.

Many trails wind through these enchanted woods, giving the tourist an opportunity to forget the cares of business life and see Nature at its best.

In the upper area of this zone the squaw grass, white rhododendron, fools huckleberry, mountain-ash, and others are typical plants.

At about 4,500 feet, in the open places, the plants of the higher regions often blend with those of the forest areas.

At this elevation the grassy meadows and the most colorful floral beauty of the park begin. As elevation increases, the groups of trees diminish in both number and size until timberline is reached, when they form prostrate mats at about 6,700 feet.

Avalanche lilies in Indian Henrys Hunting Ground. Rainier National

Park Co. photo.

The region of the greatest floral beauty is about 5,500 feet. Here the plants are large, growing in fertile soil, aided by abundant moisture from the melting snows and the warm summer sun. All colors are represented. The principal plants having red flowers in this zone are Indian paintbrush, Lewis' monkeyflower, red heather, rosy spiraea, red pentstemon, and the fireweeds; those having white flowers are valerians, white heather, mountain dock, saxifrages, avalanche lilies, western anemone, several umbelliferous plants, and the cudweeds; those having blue flowers are speedwells, lupines, mertensias, and some pentstemons; those having yellow flowers are the arnicas, potentillas, buttercups, glacierlily or yellow deertongue, mountain-dandelions, and yellow mimulus or monkeyflowers.

The principal plants in the pumice fields at or above timberline are the mountain phlox, golden-aster, Lyall's lupine, yellow heather, scarlet pentstemon, purple phaclia, golden draba, and smelowskia. The last two vie with each other for attaining the highest altitude. Between 600 and 700 flowering plants are native to Mount Rainier National Park.

THE FORESTS

The forests of the Mount Rainier National Park contain few deciduous trees, but are remarkable for the variety and beauty of their conifers. The distribution of species and their mode of growth, the size of the trees, and the density of the stand are determined, primarily, by the altitude.

The dense evergreen forests characteristic of the lower western slopes of the Cascades extend into the park in the valleys of the main and west fork of White River, the Carbon, the Mowich, the Nisqually, and the Ohanapecosh. Favored by the warm and equable temperatures and the moist, well-drained soil of the river bottoms, and protected from the wind by the enclosing ridges, the trees are perfectly proportioned and grow to a great height. The forest is of all ages from the seedling concealed in the undergrowth to the veteran 4 to 8 feet in diameter and over 600 years old. The average increase at the stump in valley land is about 1 inch in 6 years. A Douglas fir growing along the stage road between the park boundary and Longmire, at the age of 90 to 120 years, may have a breast diameter of 20 inches and yield 700 feet of saw timber. But many of the trees of this size may be much older on account of having grown in the shade or under other adverse conditions. The trees between 200 and 300 years of age are often 40 to 50 inches in diameter. The largest Douglas firs are sometimes over 600 years old and 60 to 100 inches in diameter. Up to 3,000 feet, the forests about Mount Rainier are composed of species common throughout the western parts of British Columbia, Washington, Oregon, and northern California. The dominant trees are the western hemlock, the Douglas fir, and western red cedar. Other trees at these altitudes are the amabalis fir, grand fir, and Western yew, the last being an evergreen tree but not a coniferous species. While these trees compose the type peculiar to the bottom lands, they are not confined to it, but extend to the ridges and continue to be the prevailing species is up to 3,000 feet. The stand on the mountain slopes is lighter and more open, and the trees are smaller. Huckleberry bushes and other shrubs adapted to the drier soil of the foothills, Oregon grape, and salal take the place of the tall and dense undergrowth of the bottom lands, and the amount of fallen timber is noticeably less.

Between the elevations of 3,000 and 4,500 feet the general character of the forest is intermediate between that of the lowland type and the subalpine growth of the high mountains. The forest is continuous, except where broken by extremely steep slopes and rocky crests where sufficient soil has not accumulated to support arborescent growth. In general, there is little undergrowth. The stand is fairly close on flats, benches, and moderate slopes, and more open on exposed situations and wind-swept ridges. The prevailing trees are the amabilis and noble fir and Alaska cedar and western white pine. They sometimes grow separately in pure stands, but more often are associated. At the lower limits of this type they are mixed with the Douglas fir and hemlock, while subalpine species appear at the upper limits.

Mount Rainier reflected in Mirror Lake—Indian Henrys

Hunting Ground. Copyright, Asahel Curtis.

A large part of the area above the 4,500-foot contour consists of open, grassy parks, rocky and barren summits, snow fields, and glaciers. Tracts of dense subalpine forest occur in sheltered locations, but they are nowhere very extensive, and their continuity is broken by open swamp glades and meadows and small bodies of standing water. The steep upper slopes of the spurs diverging from the main ridges are frequently covered with a stunted, scraggy growth of low trees firmly rooted in the crevices between the rocks. The most beautiful of the alpine trees are in the mountain parks. Growing in scattered groves and standing in groups or singly in the open grassland and on the margins of the lakes, they produce a peculiarly pleasing landscape effect which agreeably relieves the traveler from the extended outlook to the snow fields of the mountain and broken ridges about it. At the lower levels of the subalpine forest the average height of the largest trees is from 50 to 60 feet. The size diminishes rapidly as the elevation increases. The trees are dwarfed and their trunks are bent and twisted by the wind. Small patches of low, weather-beaten, and stunted mountain hemlock, alpine fir, and white-bark pine occur up to 7,000 feet. A few diminutive white-barked pine grow above this elevation. The trunks are quite prostrate, and the crowns are flattened mats of branches lying close to the ground. The extreme limit of tree growth on Mount Rainier is about 7,500 feet. There is no distinct timberline.

Notwithstanding the shortness of the summer season at high altitudes, the subalpine forests in some parts of the park have suffered severely from fire. There has been little apparent change in the alpine burns within the last 30 years. Reforestation at high altitudes is extremely slow. The seed production is rather scanty, and the ground conditions are not favorable for its reproduction. It will take more than one century for nature to replace the beautiful groves which have been destroyed by the carelessness of the first visitors to the mountains. At low elevations the forest recovers more rapidly from the effects of fire. Between the subalpine areas and the river valleys there are several large, ancient burns which are partly reforested. The most extensive of these tracts is the Muddy Fork Burn. It is crossed by the Stevens Canyon Trail from Reflection Lakes to the Ohanapecosh Hot Springs. This burn includes an area of 20 square miles in the park and extends north nearly to the glaciers and south for several miles beyond the park boundary nearly to the main Cowlitz River. The open sunlit spaces and wide outlooks afforded by reforested tracts of this character present a strong contrast to the deep shades and dim vistas of the primitive forest. On the whole, they have a cheerful and pleasing appearance very different from the sad, desolate aspect of the alpine burns, which less kindly conditions of climate and exposure have kept from reforestation.

Nature guide party at Sunrise. Rainier National Park Co. photo.

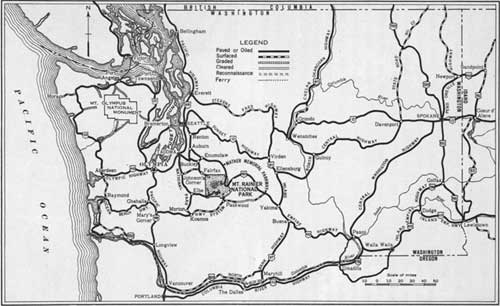

Approach roads to Mount Rainier National Park.

HOW TO REACH THE PARK

BY AUTOMOBILE

Paradise Valley and Southwest Section of Park.—A 56-mile paved road leads from the Pacific Highway at Tacoma to the Nisqually Entrance to the park. Motorists coming from the south may turn east off the Pacific Highway at Mary's Corner, 86 miles north of Portland. Over this paved and oil-surfaced route it is 74 miles from Mary's Corner to Nisqually Entrance.

At Nisqually Entrance auto permits, costing $1, are obtained. One permit entitles the auto to which it is issued to come into any of the four park entrances any number of times during the calendar year.

A 20-mile road leads from the entrance through Longmire to Paradise Valley. Half the distance is hard surfaced with oil macadam.

One of the most interesting features along the park approach road from Tacoma is the Charles Lathrop Pack Demonstration Forest of the University of Washington, where the traveler may see how young trees are grown for forest planting and how they are handled for continuous forest production. From this unique "show window" forest the highway follows impressive Nisqually Canyon for several miles.

Yakima Park (Sunrise) and Northeast Section of Park.—Motorists may approach this section of Mount Rainier National Park either from Enumclaw, 42 miles west of the park checking station at White River, or from Yakima, 76 miles east of the checking station. Naches Highway, which goes through the northeast corner of the park, crosses the Cascade Mountain Range at Chinook Pass to connect the two cities. The entire east-west road as well as the 14 miles of highway from the checking station to Yakima Park is oil macadam surfaced. A picnic ground is provided at Tipsoo Lakes near the summit of the mountain range which forms the eastern park boundary.

Auto permits are obtained at the checking station for $1. One permit entitles the car to which it is issued to come into any of the four park entrances any number of times during the calendar year.

Dedicated in honor of Stephen T. Mather, first Director of the National Park Service, a strip of land on either side of the highway leading down both sides of the Cascade Divide has been set aside as Mather Memorial Parkway. This parkway is 50 miles long.

Carbon River and Northwest Section of Park.—From Enumclaw a 22-mile road, half of which is paved, leads to the northwest corner of the park. Throughout the summer a passable road is maintained 6 miles within the park to a point 2-1/2 miles from Carbon Glacier. No automobile permit is needed, but visitors are requested to register. Trails lead to various lakes, glaciers, streams, and flower fields in the "wilderness area" of this park.

Ohanapecosh Hot Springs and Southeast Section of Park.—Approach to Ohanapecosh is made on paved and oil-surfaced roads via Kosmos, a point 65 miles south of Tacoma and 115 miles northeast of Portland, via Mary's Corner. A 42-mile gravel road leads east from Kosmos to Ohanapecosh Entrance. No auto permit is necessary, but visitors must register.

Waters from the Hot Springs are piped into a bathhouse on the bank of Ohanapecosh River. Visitors may use the hot mineral waters for a nominal price.

BY RAILROAD AND AUTOMOBILE STAGE

The three gateway cities to Mount Rainier National Park—Yakima, Seattle, and Tacoma—are reached by three transcontinental railroads—the Northern Pacific, the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul & Pacific, and the Great Northern. The Union Pacific Railroad serves Seattle and Tacoma. The park is reached from Seattle, Tacoma, and Yakima by Rainier National Park Co. stages.

Daily stage service from Tacoma and Seattle to Longmire is offered throughout the year. When snow conditions permit, this service is available through Longmire to Paradise Valley.

Stage service is obtainable from Seattle, Tacoma, and Yakima to the Yakima Park Section in the spring and until Labor Day if snow conditions are favorable. After Labor Day and until that portion of the park is closed by snow, touring cars with drivers may be rented in Tacoma or Seattle for transportation to Yakima Park; however, this service is not available in the city of Yakima.

There are different schedules and rates for the summer season (June 15 to Sept. 15) and the winter season (Sept. 16 to June 14).

BY AIRPLANE

High speed, de luxe airplane service from all points in the United States to Seattle and Tacoma is available via United Air Lines and Northwest Air lines. Direct overnight service is available from eastern and midwestern cities. Leaving New York at noon, one may arrive in Tacoma or Seattle in time for breakfast the next morning and drive to the park before lunch.

ADMINISTRATION

The representative of the National Park Service in charge of the park is the superintendent, Owen A. Tomlinson. A force of rangers assists this officer in protecting the reservation. Exclusive jurisdiction over the park was ceded to the United States by act of the Washington Legislature, dated March 16, 1901, and accepted by Congress by act approved June 30, 1916 (39 Stat. 243). Edward S. Mall is the United States commissioner.

PUBLIC CAMP GROUNDS

Comfortable camp grounds are maintained throughout the park for the convenience of those visitors who bring camping equipment. Modern camp grounds at Longmire, Paradise Valley, and Yakima Park are equipped with stoves, wood, tables, water, and sanitary facilities. Camps at Ohanapecosh, White River, Tahoma Creek, and Ipsut Creek, although less developed, have similar facilities. At Tahoma Creek water must be taken from the stream.

Food supplies may be purchased at Longmire, Paradise Valley, Yakima Park, and Ohanapecosh but campers must bring their own tents, bedding, cooking utensils, and other provisions.

POST OFFICES

The post offices are Longmire, Wash., the entire year; and Paradise Inn, Wash., and Sunrise Lodge, Wash., from July 1 until Labor Day.

COMMUNICATION AND EXPRESS SERVICE

Local and long-distance telephone service is available at all hotels and at other points in the park. Telegrams may be received or sent from hotels. All telephone lines are owned and operated by the National Park Service.

Express shipments received at any of the hotels or camps will, upon payment of charges, be forwarded by the Rainier National Park Co., and likewise the company will receive and deliver express shipments for its patrons at reasonable rates.

MEDICAL SERVICE

During the summer season a trained nurse, employed by the Rainier National Park Co., is stationed at Paradise Inn and at Yakima Park, and first-aid facilities are maintained at Longmire. A physician, having offices near the Nisqually Entrance to the park throughout the year, may be summoned. In cases of accident, illness, or serious injury park rangers assist visitors in contacting the doctor.

During the winter sports season a physician maintains offices in Paradise Valley each week-end. Park rangers are at hand in Paradise Valley to help skiers who may receive minor injuries.

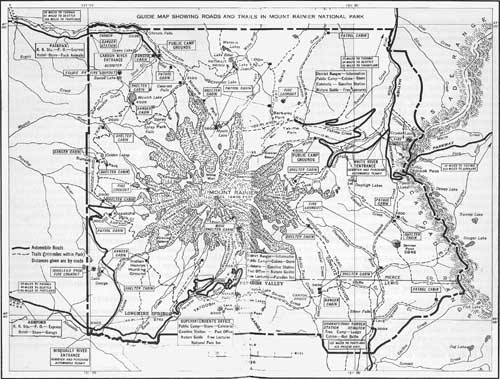

GUIDE MAP SHOWING ROADS AND TRAILS IN MOUNT RAINIER NATIONAL PARK

(click on image for a PDF version)

FISHING

No license is required to fish in the park.

Good fishing may be obtained in park lakes and streams where fish of the following species have been planted: Rainbow, native cutthroat, Montana black spotted cutthroat, steelhead, eastern brook, and Loch Leven. Flies may be used with good results toward the end of the season when high water has subsided. Streams of glacial origin, with the exception of the Ohanapecosh River, contain too much sediment for good results during July and August but are good fishing in the spring and fall months. Lakes are open to fishermen from June 15 to September 30, inclusive, unless otherwise posted as closed. Streams are open from May 1 to October 31, inclusive, unless posted as closed. A limited supply of fishing tackle and bait may be purchased at Reflection Lake near Paradise Valley.

TRAILS

The most spectacular scenery and fascinating natural features are reached by trails of varying lengths leading from roads and developed areas. Inexperienced hikers may take many interesting trips on well-maintained trails with complete safety.

Park rangers will gladly furnish information and help plan trips to suit the individual's time and ability.

Wonderland Trail, a 95-mile circuit of the peak, affords great pleasure to those who wish to enter remote areas. Over-night shelters are provided along the trail. (See map in center of pamphlet.)

WHAT TO WEAR

To obtain the most enjoyment from a visit to Mount Rainier National Park, visitors should come prepared for hiking and saddle-horse riding. Wear reasonably warm clothing and be prepared for sudden changes of weather and altitude.

Particular attention should be given to footwear for hiking. Medium-weight shoes, hobnailed, will suffice for all ordinary tramping, but for ice climbing, calks instead of hobnails are required. If guides are engaged, they will provide calked shoes, clothing, alpenstocks, colored glasses, and face paints necessary for trips over snow or ice fields.

Arrangements for guides can be made at Paradise, and hiking clothing may be rented by those who do not bring their own.

As the sun is reflected by the snow on clear days during the winter, grease paint and colored glasses are entirely necessary for enjoyment of winter sports. Woolen clothing (preferably ski suits) is desirable during the winter to shed the snow and moisture. Ski equipment, including clothing, ski boots, skis, poles, and other necessaries may be rented at Paradise Guide House. Glasses and grease paint may be purchased there.

MOUNT RAINIER SUMMIT CLIMB

As a safety precaution, all climbers attempting the summit of Mount Rainier (14,408 feet high) are required to register with a district ranger before starting. To insure reasonable chances of success, climbers must present evidence that they are physically capable; that they have knowledge and experience in similar hazardous climbing; and that they have proper equipment and supplies.

Generally speaking, Mount Rainier is a difficult peak to climb. The route to the summit is not a definitely marked path. Dangerously crevassed ice covers a large proportion of the mountain's flanks, and the steep ridges between glaciers are composed of treacherous crumbling lava and pumice.

Weather on the mountain is fickle. Midsummer snow storms, always accompanied by fierce gales, rise with unexpected suddenness.

Preparation by those who have set their ambition on making the ascent is far more than merely the collection of proper equipment. Thorough seasoning of oneself by making several less strenuous climbs up rocky peak and short distances over glaciers is necessary before leaving for the "top." An extensive study of conditions, hazards, and precautions is essential before starting.

Need for securing services of a competent guide is virtually imperative. Guides not only show the way but tell visitors how to climb, when to rest and to take nourishment, and take care of persons exhausted or sick. The security enjoyed on a guide-conducted party far exceeds in value the moderate expense of the service.

Paradise Valley, logical starting point, is at an altitude of 5,557 feet and is 7 miles from the summit. Guides and necessaries may be secured there.

Parties leave Paradise Valley in the afternoon so as to reach Camp Muir, 4 miles away, before dusk. At this 10,000-foot elevation a shelter and very simple accommodations are provided. After a few hours rest, climbers start the last 3 miles of the trip about 1 or 2 a. m.

From Camp Muir over rough lava blocks on Cowlitz Cleaver to the base of Gibraltar Rock is a taxing climb. From here up through the "chutes" to the saddle above Gibraltar, climbers encounter the most serious difficulties of the trip. There is ever danger of persons above starting rock debris and ice fragments that may injure those below.

From Gibraltar remains a long, fatiguing climb up a continuous ice slope. Gaping crevasses must be avoided.

The rim of the south crater is usually reached about 8 a. m. Here climbers may record their ascent in registers within metal cases. Those having the strength may go on to Columbia Crest, the snow dome that constitutes the highest summit of the mountain.

Return to Paradise Valley is easily made in from 5 to 6 hours, but summit parties must be below Gibraltar Rock before noon, out of the path of falling rocks. Afternoon heat causes melting of the ice, thus allowing rocks to fall into the "chutes" through which summit climbers pass both on the ascent and descent.

The simpler the diet, on the whole, the more beneficial. Never eat much at a sitting on the ascent, but eat often and a little at a time. The conventional diet is not suitable for the strenuous athletic work of summit climbing. Beef tea, lean meat, all dry breakfast foods, cocoa, sweet chocolate, crackers, hard tack, dry bread, rice, raisins, prunes, dates, and tomatoes are in order.

Special mountain-climbing equipment is indispensable to a safe ascent of Mount Rainier. Heavy boots with calks and hobnails are necessary for the rock work of the climb and crampons are needed for the climb over ice. Alpenstocks, ropes, and first-aid kits are essential. Grease paint, amber glasses, and warm woolen clothing are needed for protection from the weather. Proper equipment may be rented from the guides at Paradise Valley.

Although the mountain has been conquered by other routes than by Gibraltar Rock, ascents from other starting points are for only the most experienced mountain climbers. No guides are available; the trips are long and tiring; and no shelters are provided.

Mount Rainier in winter garb. Rainier National Park Co. photo.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

1936/mora/sec2.htm

Last Updated: 20-Jun-2010