CELEBRATING THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE CENTENNIAL • 1916-2016

Mabry Mill along Blue Ridge Parkway

To celebrate the centennial of the National Park Service, each month we will reflect back on various aspects of the development of the National Park Service and the National Park System. Last month we took a brief look at NPS history; the next few months we will explore in more depth key periods of National Park Service history: the expansion of the National Park Service and System in the 1930s, the key role in the development of visitor facilities by the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) of 1933-1942, the ten-year effort known as Mission 66 to expand/upgrade visitor facilities to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the National Park Service in 1966, and finally the largest single expansion of the National Park System in 1980 due to the passage of the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA). Written by NPS historians Harlan D. Unrau and G. Frank Williss in 1983, the Administrative History: Expansion of the National Park Service in the 1930s chronicles the transfer of U.S. Forest Service-managed national monuments, as well as military parks/battlefields from the Secretary of War to the National Park Service, along with the subsequent reorganization of the National Park Service in 1933. What began as a National Park System in 1916 comprising 37 units (all but one west of the Mississippi River) evolved to 137 units by 1933. New Deal emergency work relief programs also commenced in 1933, which will be examined in closer detail next month. To learn more details about expansion of the National Park System, you are invited to read these additional books. Administrative History: Expansion of the National Park Service in the 1930s Foreword This scholarly study by historians Unrau and Williss deals with a bewildering but exciting time approximately a half century ago when an extraordinary combination of circumstances occurred, having profound and lasting effect upon the National Park Service and leading, moreover, to sweeping changes in the Nation's ways of conserving and using its important historic places. Horace Albright became the second director of the Service in the same year (1929) in which Herbert Hoover was inaugurated President of the United States. Also it happened in that year that the stock market collapsed and the Great Depression descended upon the country, forcing public attention to shift abruptly from international matters where it so long had been centered to urgent new economic and social issues. The new public mood, demanding positive governmental action in dealing with the many problems now arising, fitted nicely the natural inclinations of the incoming director, who! skillful administrator in the Service as he had already demonstrated, was nevertheless a man of unusual imagination and daring, quick to seize upon innovative solutions to unusually complicated problems. Intuitively, too, Mr. Albright sensed the fact that the President, despite a certain cautious nature, greatly desired to do whatever he could to alleviate the harsh realities of the Depression- -even to the extent of putting into operation his own special kind of "New Deal." So the director had scarcely taken up his new duties in the Service before he was involved in the construction of the George Washington Memorial Parkway, extending from above Georgetown all the way to Mount Vernon; also in the development with congressional approval of two new major parks, Shenandoah and Great Smoky Mountains, with connecting links, the Skyline Drive and the Blue Ridge Parkway; and, as if all this were not enough, Mr. Albright had persuaded those just then engaged in the program for George Washington's birthplace to turn over the site to the Service along with sufficient funds to complete the "restoration" and to ensure its temporary custody and maintenance. Last but certainly not least among the interests demanding the director's attention was the tremendous plan for a new "monument'' to be called Colonial, including Jamestown, Yorktown, and Williamsburg in Virginia. All three historic sites were to be connected by a parkway, and in this connection was the astonishing proposal of Mr. John D. Rockefeller, Jr., to "restore" in its entirety colonial Williamsburg. Mr. Rockefeller, already a warm friend of the Service and of Mr. Albright himself, was ready to help acquire the lands necessary for the Service's construction of the proposed parkway, just as he had recently helped in the Grand Teton-Jackson Hole park project in Wyoming and earlier at Acadia National Park in Maine. A busy Albright could still find time to plan in 1931 the giant celebration and pageant at Yorktown, commemorating the 150th anniversary of the surrender there of Lord Cornwallis to General Washington. Among the thousands in attendance that bright October day were President Herbert Hoover himself and his cabinet as well as the thirteen governors of states representing the original colonies. One of these was Franklin D. Roosevelt, and another distinguished guest was the grand old warrior of World War One fame, General John J. Pershing. The Yorktown affair proved to be an unqualified success, let it be noted, and it had the effect of putting the Service very high in the public mind as an agency concerned with the protection and skillful use of a major historic site. With the momentum thus engendered, it was perhaps less difficult in 1932-33 to persuade Congress to set aside under Service jurisdiction another great historic shrine, to be known henceforth as the Morristown (New Jersey) National Historical Park. The emergence in 1933 of a full scale Branch of Historic Sites and Buildings, the product of a series of "New Deal" measures and therefore at first temporary in nature, followed logically certain earlier steps taken by the National Park Service in the field of historical preservation and use. In this connection, the creation in 1930 of Colonial and George Washington's birthplace "monument" in Virginia as well as the passage by Congress of the Morristown National Historical Park bill in 1933 naturally deserve attention. Then, too, in 1931, linked with plans for the never-to-be-forgotten Yorktown pageant and celebration, there had been organized within the Branch of Education and Interpretation a so-called "Division of History," and that in turn had given rise to the appointment of a chief historian and two field park historians. Plans for the new historical branch were underway almost as soon as the chief historian entered upon his duties! but, lacking at that juncture the necessary funds for the project, it remained for developments transpiring in the first year of the administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt to make possible the decision to proceed. First, with the far-reaching reorganization of government, there were transferred that year to the Service from several other departments and agencies a great galaxy of historic places including the national military parks and monuments, the Statue of Liberty, the Spanish forts of St. Augustine, Florida, and Fort McHenry at Baltimore, the scene of the writing of the National Anthem. The second major development at that time was the launching of numerous "New Deal" programs (like the "alphabet series," beginning with the CCC and followed by projects such as the PWA, the FERA, and WPA), designed in each case to give government employment to people out of work. It may require a bit of imagination out of the ordinary to find a logical connection between a CCC operation in a newly acquired military park, placed there to develop trails and markers or for maintenance purposes, and the realization of a new Branch of History and the appointment of large numbers of individuals designated as "historical technicians'' to perform a variety of duties within the Service. Nevertheless, the connecting link, however tenuous and difficult to see, was established. As a result, the chief historian, now placed in administrative charge of the new branch, sought to fill a myriad of new positions; and in the weeks and months that followed, hectic in the extreme though they were, this task was fulfilled, as well as the responsibility for training scores of new recruits ("academic greenhorns" they sometimes were called), so that eventually they might look forward to becoming bona fide Park Service professionals.

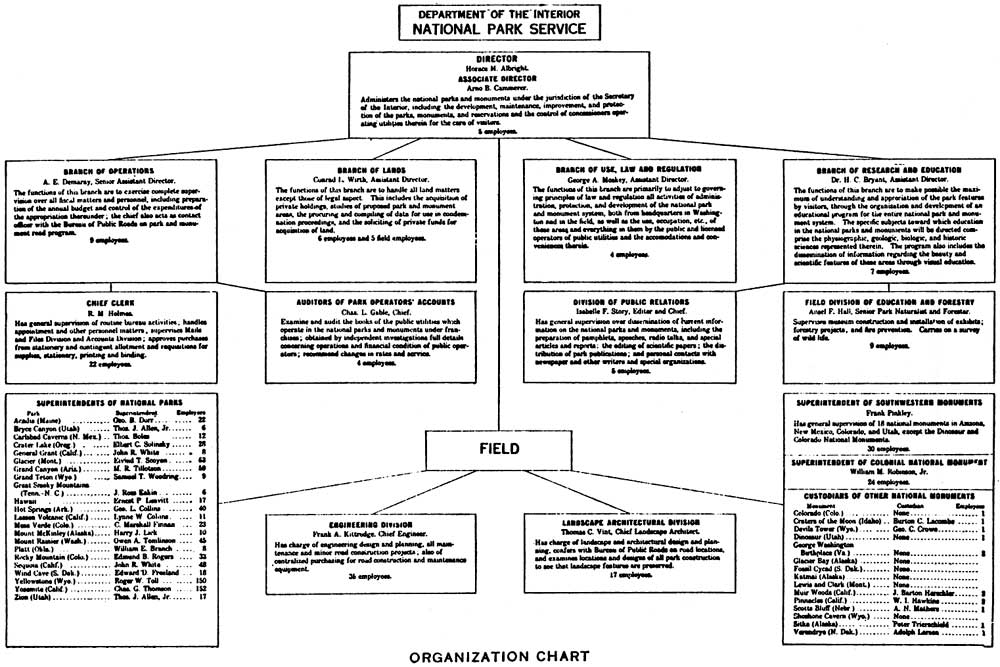

Then, of course, there were many other demands upon the acting chief of the new branch. He was expected to visit each of the newly acquired historical areas and overlook the work of the personnel there; he was also expected to visit and investigate many places being suggested by members of Congress and their clients for possible inclusion in the Service; and then there were numerous calls for special appearances at meetings on the "Hill" and before congressional committees, as well as requests to speak upon the theme of history within the Service; and in certain instances, too, the chief historian might be expected merely to act as an official representative of his organization at whatever occasion there might be. On a certain Fourth of July, for example, the "chief" traveled to Antietam and delivered the principal address of the day, after which with a police escort leading the way he was taken all the way to Gettysburg, where, being the official representative of the Department of the Interior, he sat directly behind the President (Mr. Roosevelt) while listening to the speech there being delivered. Each "chore," while certainly interesting and challenging, could be time consuming, too, so that on many occasions there just did not seem to be enough hours and days in which to get the work done. Nevertheless, the time came in 1935 to design and write, and then to persuade Congress to enact, a Historic Sites Act, providing a formal and legal basis for the branch within the Service and laying the foundation for a national program of permanent nature in the field of historic site preservation, all of course under National Park Service leadership. With this task accomplished, the moment had come for the realization finally of the grand design envisioned by Horace Albright and shared by him with this writer in their first legendary encounter so long ago in a railroad station in Omaha, Nebraska. By Dr. Verne E. Chatelain, Preface The following study, which examines one of the most significant decades in the development of the National Park Service, is one of the first in what will be a series of administrative histories of the National Park Service. Initiated by NPS Chief Historian Edwin C. Bearss, the administrative history program will result in studies that will not only be of importance to managers in the Service, but will be of interest to the general student as well. Any study is the result of the combined efforts of a number of people, and this one is no exception. Edwin C. Bearss initiated the program, gave us the project, and was a source of encouragement throughout preparation of the project. Barry Mackintosh, NPS Bureau Historian, provided general administrative oversight of the project. Harry Butowsky, Historian, WASO, supplied us with his study on nomenclature and the supporting documentation for it. Ben Levy, senior historian in the Washington office, helped us to find material on the NPS Advisory Board and shared his insights into the Historic Sites Act of 1935. Gerald Patten, Assistant Manager, and Nan V. Rickey, Chief, Branch of Cultural Resources, Mid-Atlantic/North Atlantic Team, Denver Service Center, provided encouragement for the project and released us from team-related work so that we could work on it. John Luzader took time from his own work to read drafts and offer valuable advice. Mr. Luzader also supplied us with information that he had uncovered in his own research. David Nathanson, Chief, Branch of Library and Archival Services, Harpers Ferry Center, and members of his staff, Richard Russell and Ruth Ann Herriot, provided us with useful suggestions relative to the availability of manuscript and printed materials for the study. Tom Lucke, Environmental Coordinator, Southwest Regional Office, sent us material on Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument. Ruth Larison, Rocky Mountain Regional Office Library was helpful in obtaining material. Shirley Luikens, Advisory Boards and Commissions, Washington office, assisted us in locating relevant material in her office. Douglas Caldwell, Anthropology Division, Washington office, provided us with a draft of William C. Tweed's "Parkitecture: Rustic Architecture In the National Parks." One of the unexpected benefits of undertaking this study has been the opportunity to contact a number of former Park Service people who were active in the 1930s. We are indebted to all those who took the time to set down their reactions to the events. Particular thanks goes to George A. Palmer, who sent us additional information and made helpful suggestions. Additionally, thanks go to the staffs of the various libraries we visited: Library of Congress; National Archives; Bancroft Library, Manuscripts Division, University of California, Berkeley; University Research Library, Division of Special Collections, UCLA; Department Library and Law Library, Department of Interior; and University of Colorado, Government Publications Division, Boulder, Colorado. Finally, Helen Athearn of the Mid-Atlantic/North Atlantic Team, Denver Service Center, did the paper work associated with the project, and Evelyn Steinman typed the manuscript. Harlan D. Unrau Chapter One: "They have grown up like Topsy"1 Today, the 14,627 people of the National Park Service are responsible for the administration of 334 units that comprise the National Park System.2 This is a far cry from the day some fifty-five years ago,when eleven people manned the central office in Washington D.C., and the National Park System consisted of fifteen national parks and twenty national monuments.3 The development of the National Park Service and the system it administers was evolutionary. This study examines one phase in this process—the 1930s. In that decade—surely one of the most significant and creative in the service's history—both the organization and the system it administers were transformed. A. National Parks and Monuments Under the Department of the Interior, 1872-1916 Any history of the National Park Service does not begin with the establishment of the bureau. Rather, it must begin some forty-five years earlier, on March 1, 1872. On that day, President Ulysses S. Grant signed an act that set aside a "tract of land . . . near the head-waters of the Yellowstone River . . . as a public park or pleasuring-Ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people."4 The creation of Yellowstone National Park was the world's first attempt to preserve a large wilderness area as a national park. The national park idea, as expressed first there, quite rightly may be considered to be one of America's unique contributions to world civilization.5 Neither the president nor Congress realized what they had done, however, would be emulated all over the world. Nor did the Yellowstone National Park enabling act nor the separate acts that established additional national parks that followed represent a conscious effort to create a national park system.6 Between 1872 and August 16, 1916, when a bureau to administer them was finally established, Congress set aside fourteen additional national parks: Mackinac Island (March 3, 1875), Sequoia (September 25, 1890), Yosemite (October 1, 1890), General Grant (October 1, 1890), Mount Rainier (March 22, 1899), Crater Lake (May 22, 1902), Wind Cave (January 9, 1903), Sullys Hill (April 27, 1904), Platt (June 29, 1906), Mesa Verde (June 29, 1905), Glacier (May 11, 1910), Rocky Mountain (January 26, 1913), Hawaii (August 1, 1916), and Lassen Volcanic (August 9, 1916).7 In the meantime, a growing number of people, scholars and non-scholars alike, were becoming increasingly concerned over the destruction of the nation's antiquities, and loss, therefore, of a considerable body of knowledge about its past. Of particular concern was the damage inflicted by the "pothunters" on the prehistoric cliff-dwellings, pueblos, and Spanish missions in the Southwest, although sites elsewhere were certainly not immune.8 In 1906, following a lengthy, if uncoordinated campaign, Representative John F. Lacey of Iowa secured passage of his "Act For the Preservation of American Antiquities."9 The Antiquities Act provided for the creation of a new kind of reservation. Thereafter certain objects of historic, prehistoric, or scientific interest could be declared "national monuments." Avoiding the cumbersome legislative process required for the establishment of national parks, the act authorized the president to set aside such sites on the public lands by proclamation.10 Of particular importance to this study, the Antiquities Act did not place administrative responsibility of all national monuments in one agency. Rather, jurisdiction over a particular monument would remain with "the Secretary of the department having jurisdiction over the lands on which said antiquities are located."11 As a result, both the Agriculture and War departments as well as Interior would administer monuments until 1933, when Executive Order 6166 transferred all to the Department of the Interior.12 In 1911 Frank Bond, chief clerk of the General Land Office, ventured that, differences in process of establishment aside, national parks and monuments were as alike as "two peas in a pod."13 In practice his observation had a certain validity. Three of the monuments administered by the Interior Department later formed nuclei of national parks.14 Additionally, several national monuments administered by the Department of Agriculture--Lassen Peak and Cinder Cone, Grand Canyon, and Mount Olympus--became national parks.15 Yet, as difficult as it was sometimes to perceive, there was a difference between national parks and national monuments. Through the period under discussion, at least, the difference would be reflected in the administration of the two areas. Generally, the monuments were smaller, although this distinction disappeared when one considered Katmai and Glacier Bay national monuments, which were 2,792,137 and 2,803,137 acres respectively.16 Although obviously a most subjective thing, the national parks were generally thought to have met some higher standards than did the national monuments--were areas of outstanding scenic grandeur.17 Administratively, national monuments were areas deemed to be worthy of preservation, and were set aside as a means of protection from encroachment. A national park, on the other hand, was an area that would be developed to become a "convenient resort for people to enjoy."18 On September 24, 1906, President Theodore Roosevelt issued a proclamation setting aside Devils Tower, a 650-foot-high volcanic shaft on the Wyoming plains, as the first national monument.19 Between that date and August 25, 1916, Presidents Roosevelt, William H. Taft, and Woodrow Wilson set aside nineteen more sites to be administered by the Department of the Interior. Seven of those sites were of historical or prehistorical significance: El Morro (December 8, 1906), Montezuma Castle (December 8, 1906), Chaco Canyon (March 11, 1907), Tumacacori (September 15, 1908), Navajo (March 20, 1909), Gran Quivera (November 1, 1909), and Sitka (March 23, 1910).20 Twelve others, like Devils Tower, were of scientific significance. With the exception of Sieur de Monts (July 8, 1916) in Maine, they were in the West: Petrified Forest (December 18, 1906), Muir Woods (January 9, 1908), Natural Bridges (April 16, 1908), Lewis and Clark Cavern (May 11, 1908), Mukuntuweap (July 31, 1909), Shoshone Cavern (September 21, 1909), Rainbow Bridge (May 30, 1910), Colorado (May 24, 1911), Papago Saguaro (January 31, 1914), Dinosaur (October 4, 1915), and Capulin Mountain (August 9, 1916).21 The twelve national parks and thirteen national monuments that existed before 1910 had, in the words of Secretary of the Interior Walter L. Fisher, "grown up like topsy."22 Congress had set aside certain areas, and had provided meager funds for their administration. It had not, however, provided for any central administrative machinery, other than assigning that function to the Secretary of the Interior. The Department of the Interior displayed little more interest in the parks than did Congress. Before 1910, no official or division in Interior was anything more than nominally responsible for the national parks. What little attention was given then came from whomever had extra time, or the inclination to do so.23 This meant that there existed, into the second decade of the century, essentially no central administration for the national parks. Nor had there been any effort to spell out a general national administrative policy for the parks before 1915, when Mark Daniels so attempted.24 Although the Secretary of the Interior was responsible for the administration of the parks, any actual control existed on paper only. Each of the twelve national parks was a separate administrative unit, run as well, or as poorly, as the politically-appointed superintendent did so.25 Congress made no general appropriation for the national parks; money was made available to each separate park. The amount received varied, generally, in a direct ratio to the superintendent's political influence.26 As late as 1916, rangers were appointed by the individual parks, not the department, and could not be transferred from park to park.27 It was no easier to transfer equipment between parks, nor were approaches to common problems often shared.28 In his 1914 testimony on a bill to create a National Park Service, Secretary of the Interior Adolph C. Miller stated that the situation "is not so serious, but it is very bad."29 Miller was an optimist. Physical developments in the national parks, particularly with respect to sanitation facilities, were hopelessly inadequate for the growing number of park visitors.30 Mount Rainier, Crater Lake, Mesa Verde, and Glacier national parks received little more than custodial care.31 The civilian administrators had early proven themselves incapable in Yellowstone, Sequoia, General Grant, and Yosemite, and had been replaced by the Army.32 Although the army officers performed a creditable job, the arrangement in Yellowstone, at least, resulted in a most confusing administration at the park level:

Administratively, the national monuments under the jurisdiction of the Department of the Interior were separate from the national parks. From the passage of the Antiquities Act until the creation of the National Park Service, the General Land Office was responsible for the administration of the national monuments.34 Having a clearly defined responsibility in this case did not mean, however, more efficient administration. Congress steadfastly refused to appropriate even the modest sum of $5,000 requested for preservation, administration, and protection of all units.35 When an appropriation was finally made in 1916, it was only $3,500.36 Because no appropriation was forthcoming it was not possible to provide on-site custodial care. The person charged with immediate supervision of Montezuma Castle, Petrified Forest, Tumacacori, and Navajo national monuments, for example, was Grutz W. Helm, whose office was in Los Angeles.37 The story that emerges from the records is one of decay, spoliation, and vandalism of the national monuments. It is little wonder that the commissioner requested in 1913 that responsibility for the national monuments be transferred from his bureau back to the department.38 In many respects, Tumacacori National Monument was a special case, because the Forest Service actually administered the site at the local level, while ultimate jurisdiction remained in the Department of the Interior. This somewhat complicated matters. The problems of protection there, however, were illustrative of those that existed elsewhere. While responsible for the area, the Forest Service made no improvements, and the only direct supervision came when forest rangers happened to visit the site in the course of other duties, something that did not happen often. By August 1913, Forest Service personnel indicated that "Tumacacori Mission . . . is suffering misuse and is in a very dilapidated condition."39 Recognizing that the estimated $5,000 needed to prevent further deterioration would not be available, R.T. Galloway, acting Secretary of Agriculture, requested that the Interior Department provide $100 to enclose a stock-proof fence.40 The fence was constructed, but only after the money was transferred from the department to the bureau, then to the Chief of the Los Angeles Land Office Field Division, who, in turn authorized Robert Selkiak, forest supervisor in Tucson, to construct the fence.41 Selkiak then arranged for construction. The problems arising from the lack of a central administrative organization did not go unnoticed by the friends of the national parks. As early as 1908, a small group of enthusiasts, led by Horace J. McFarland, president of the American Civic Association, began to lobby for the creation of a separate bureau to administer the parks.42 Between that date and 1916, some sixteen bills that proposed a new bureau to administer the parks were introduced in Congress.43 Within the Interior Department, too, the first steps were taken to centralize administration of the national parks. In 1910 the Secretary of the Interior came forward with a proposal for a park bureau and in 1911, a conference at Yellowstone Park represented the first formal effort at cooperation at the park level.44 In the absence of legislation establishing a park bureau, successive Secretaries of the Interior--Walter L. Fisher and Franklin K. Lane--tried to place park administration on a more coherent basis. By the end of 1910, general responsibility over the parks had been assigned to W. B. Acker, an assistant attorney in the secretary's office.45 Acker was also responsible for the Bureau of Education, eleemosynary (charitable) institutions in the District of Columbia, territories of Hawaii and Alaska, and the department's investigative staff.46 Moreover, he had little money to expend, and a small staff at his disposal. He was, however, devoted to the national parks, and his efforts on their behalf represented the first, halting steps toward a centralized administration. In 1913 Secretary Lane upgraded park supervision and coordination to the assistant secretarial level and appointed Adolph C. Miller, chairman of the Department of Economics at Berkeley, to fill the position.47 Miller received instructions to solve the problem of park administration. The next year, he assigned direct administrative responsibility to a General Superintendent and Landscape Engineer of the National Parks, with offices in San Francisco.48 Mark Daniels, a landscape engineer, filled the position on a part-time basis while continuing in his private practice. When Daniels resigned before the end of the year, Robert C. Marshall of the U.S. Geological Survey became the first full-time administrator of the national parks. Not only was Marshall's position a full-time one, but he also had his office in Washington, D.C.49 The appointment of a full-time general superintendent of the national parks with at least a small staff to assist him would prove to be a significant step toward establishing a unitary and coherent administration of the national parks.50 The most important step taken by the Interior Department in that regard, however, was the hiring of Stephen T. Mather and Horace M. Albright. Albright arrived first--as a clerk in the office of Assistant Secretary Miller on May 31, 1913.51 The twenty-five-year-old Albright had already proven himself an able administrator when he was directed to keep Mather, who replaced Miller as assistant secretary in January 1915, "out of trouble."52 The quietly efficient and tough-minded Albright perfectly complemented the energetic, extroverted, if sometimes erratic, Stephen Mather.53 They quickly established a working relationship based on mutual trust and respect that is rare in any organization. Neither expected to remain in government service for more than a year.54 Fortunately they did not leave as they had anticipated. The subsequent history of the national parks and the National Park Service is inextricably bound up with the careers of these two remarkable men. Stephen Mather was a self-made millionaire, whose success in the private sector rested as much on his publicity skills as it did on organization ability. It is small wonder, then, that his first inclination as Assistant Secretary of the Interior was to launch a drive to give the national parks greater visibility. Directed by a former journalist, Robert Sterling Yard, the "educational campaign was a smashing success."55 Not only did park visitation increase dramatically that first year, but the resulting publicity played no little role in the successful effort to create a separate national park bureau.56 B. National Park Service Administration, 1916-1933 The decade-long effort to secure passage of a bill creating a parks bureau in the Department of the Interior had become bogged down by congressional indifference and a bitter conflict within the ranks of the conservationists. By the summer of 1916, however, those who championed the creation of a park bureau emerged victorious, and on August 25, President Woodrow Wilson signed "An Act to establish a National Park Service, and for other purposes."57 The act provided for the creation of a National Park Service that would

As is so often the case, however, the act did not address a number of questions raised in the debates over it. Of particular importance here, it did not, as many of its supporters hoped it would, bring administration of all federal parks and monuments together in a single agency. That step would not be taken for nearly seventeen years. The act provided for appointment of a director, whose annual salary would be $4,500, an assistant director, chief clerk, draftsman, messenger, and "such other employees as the Secretary of the Interior shall deem necessary . . . ." Because no money for the new bureau was provided until April 17, 1917, the new organization could not be formed until that time, and the interim organization under Robert Marshall continued to function.58 Mather had originally intended that Marshall would be the first director of the new service. He had begun to lose confidence in Marshall's administrative ability, however, and at the end of the year, Marshall returned to his old position at Geologic Survey.59 Instead, Secretary Lane appointed Mather as first director and Albright as assistant director. Frank W. Griffith became chief clerk. Others in the office included Arthur E. Demaray and Isabelle Story from Marshall's staff, Nobel J. Wilt, a messenger, and five clerks.60 The year 1917 was not the most propitious time for launching a new federal bureau. On April 6 of that year the nation entered World War I, and money and attention were naturally diverted to the war effort. To make matters worse, Stephen Mather suffered a nervous collapse in January, and was hospitalized. It would be more than a year before he could return to work.61 That the agency took form, and was able to function as well as it did was a tribute to the ability of the twenty-seven-year-old acting director--Horace M. Albright.62 A wide range of policy and administrative issues, beyond the immediate organizational and funding questions, faced Albright and Mather when the latter returned to Washington. Relationships between the new central office and parks that traditionally had been independent had to be established. Both men wanted to put park administration on a "business-like" basis, using the expertise found in other governmental agencies to avoid unnecessary growth.63 Relationships with these organizations had to be worked out. The military still occupied Yellowstone National Park; as long as they were there, the National Park Service would not have full responsibility for the areas in its charge. In a wartime atmosphere, the very existence of parks was threatened. A clear policy regarding development had to be formulated. The national monuments suffered from years of neglect. These units had to be incorporated fully into the park system, and an effective method of administering them was necessary. Finally, it was clear that some additional parks to round out the system were needed. Yet no clear standards for national parks had heretofore been enunciated. These issues could not be dealt with in a vacuum. What was needed, despite Mark Daniels' efforts to do so in 1915,64 was the articulation of a general policy that would provide a sound basis for administration of the National Park System. On May 13, 1918, a letter from Secretary of the Interior Franklin K. Lane to Mather did just that:

The principles enunciated were substantially reaffirmed by Secretary of the Interior Hubert Work seven years later,66 and again in 1932.67 They remain the foundation of National Park Service administration today. Stephen Mather served as director of the National Park Service for twelve years, retiring January 12, 1929.68 His replacement as director was Horace Albright, who for the previous ten years, had served as both superintendent of Yellowstone National Park and Assistant Director of the National Park Service (field).69 Few people have left a greater imprint on any organization than Stephen Mather left on the National Park Service. The record of his administration was remarkable. When he became director, the system consisted of fourteen national parks and twenty national monuments, with a total of 10,850 square miles.70 When he resigned, the system encompassed twenty national parks and thirty-two national monuments with a total area of 15,696 square miles.71 Just as important, Mather had managed to stave off a series of efforts to establish national parks that he believed to be inferior, and he defeated repeated efforts to exploit those that existed.72 He carried on the publicity campaign he had begun as Assistant Secretary of Interior, and in the process stamped the national parks indelibly into the American consciousness. Recognizing that "scenery is a hollow enjoyment to a tourist who sets out in the morning after an indigestible breakfast and fitful sleep on an impossible bed," Mather had made development of park facilities a high priority, and had developed a coherent concessions policy to insure visitor comfort.73 In 1918, after no little difficulty, Mather managed to secure removal of the troops from Yellowstone. After that date, the National Park Service was solely responsible for the areas under its charge.74 The impact of Mather's administration of the National Park Service is greater than the sum total of these accomplishments. With the help of Horace Albright, he built a small, overworked organization into one that came to enjoy a reputation for efficiency, responsiveness, and devotion to its charge unparalleled in the federal government. The men who guided the service until the end of the 1930s, moreover, had served under Stephen Mather. They did not deviate far from the course he had set. Even today, some fifty-three years after he left the service, the ideals and policies enunciated by Stephen Mather serve as a guide for the National Park Service. No person was better qualified to succeed Mather as director than Horace Albright. He had been deeply involved in the administration of the park system at all levels since 1913, and had, it will be recalled, served as acting director of the service in the first, difficult months after passage of the NPS enabling act. His four years as director during the early days of the Great Depression would confirm his stature as a skillful and far-seeing administrator. In December 1928, after it had become clear that he would be the new director, Albright wrote to Robert Sterling Yard, stating his conception of his role as director:

Albright's administration did not, as he indicated, represent a break with Mather's but was, rather, an extension of it. He fought to maintain the high standards for parks established by Mather, managing to bring in Carlsbad Caverns (May 14, 1930), Isle Royale (March 31, 1931), and Morristown (March 1, 1933), as well as eleven national monuments. 76 As had Mather, Albright successfully opposed inclusion of substandard areas and went a step further when he secured elimination of Sullys Hill, a clearly inferior park.77 Mather previously had obtained civil service coverage for park rangers; Albright continued the drive for professionalization of the Service by securing the same for superintendents and national monument custodians in 1931.78 In the early 1920s, Mather had instituted an education (interpretation) program with offices in Berkeley, California.79 Albright reorganized and coordinated the work by creating a Branch of Education in the Washington office, headed by Dr. Harold C. Bryant, whose title was Assistant Director in charge of Branch of Education.80 Mather was a brilliant, but sometimes erratic administrator, whose administrative style was a highly personal one. Albright took steps, as he said he would, to create a more orderly administration that depended less on personal relationships. Of particular importance in the 1930 reorganization of the service was the delegation of authority among staff officers, something Mather had been unable, or unwilling to do.81 None of this is to say that Albright was a mere shadow of his former boss. He was too forceful a man for that. Moreover, if anything, his view of the mission of the National Park Service was broader than Mather's. This was most vividly expressed in Albright's approach to historical areas. Mather increased appropriations for the national monuments while he was director.82 In 1923, moreover, he attempted to create a more effective administration of the national monuments in the Southwest by appointing Frank "Boss" Pinkley as Superintendent of the Southwest Monuments.83 Yet, his overriding concern was with the scenic areas of the system--he paid scant attention to the historical and prehistorical areas. Albright was a long-time history buff who believed that the National Park Service had a responsibility to preserve significant aspects of the nation s past along with the great scenic areas.84 With the able help of U.S. Representative Louis Cramton of Michigan, Albright brought the National Park Service much more deeply into the field of historic preservation.85 In 1930 Albright proudly reported that the establishment of George Washington Birthplace National Monument marked "the entrance of this service into the field of preservation on a more comprehensive scale."86 Establishment of George Washington Birthplace National Monument was followed closely by Colonial National Monument on July 3, 1930, and passage of a bill on March 2, 1933, establishing the first national historical park--Morristown.87 In 1931 Albright gave institutional status to a history program in the Park Service when he hired Dr. Verne E. Chatelain as chief of the division of history in Dr. Harold Bryant's branch of research and education.188">88 Perhaps Albright's greatest contribution to historic preservation in the National Park Service was in his efforts to secure administrative responsibility of the battlefields and other historical areas administered until 1933 by the War Department. Even before the Park Service existed, Albright believed they should be administered as part of the national park system.89 Beginning in 1917 he attempted to secure passage of a bill that would transfer administration of the areas to the Park Service.90 Effective August 10, 1933, just one day after Albright retired, Executive Order 6166 transferred all the historical battlefields and monuments administered by the War Department, sixteen national monuments under the jurisdiction of the Agriculture Department, and the parks of the national capital to the Department of the Interior. C. Department of Agriculture Monuments, 1906-1933 As indicated previously, the Antiquities Act of 1906 left administration of federal parks and monuments fragmented between the departments. Between 1906 and 1933, six presidents set aside twenty-one national monuments on land administered by the Agriculture Department. All twenty-one, which were the responsibility of the Forest Service, were in the western states. Sixteen were judged significant because of their scientific value: Lassen Peak and Cinder Cone (May 16, 1908); Grand Canyon (January 11, 1908); Pinnacles (January 16, 1908); Jewel Cave (February 7, 1908); Wheeler (December 7, 1908); Mount Olympus (March 2, 1909); Oregon Caves (July 12, 1909); Devil's Postpile (July 6, 1911); Lehman Caves (January 24, 1922); Timpanogos Cave (October 14, 1922); Bryce Canyon (June 8, 1923); Chiricahua (April 18, 1924); Lava Beds (November 21, 1925); Holy Cross (May 11, 1929); Sunset Crater (May 26, 1930); and Saguaro (March 1, 1933).91 Five more were of historical importance: four of these--Gila Cliff Dwellings (November 16, 1907), Tonto (December 19, 1907), Walnut Canyon (November 30, 1915), and Bandelier (February 11, 1916)--were significant archeological remains in the Southwest. The fifth, Old Kasaan (October 15, 1910), was the ruins of a former Haida Indian village in Alaska.92 Five of the areas were transferred to the National Park Service before 1933. Grand Canyon, Lassen Peak and Cinder Cone, and Bryce formed the nuclei of national parks. Pinnacles and Bandelier were transferred for administrative purposes in 1910 and 1932, respectively.93 Before 1933 the Forest Service was able to turn aside all efforts to transfer administrative responsibility of the national monuments under its jurisdiction to the National Park Service, and they were a continuing irritant in relations between the two agencies throughout the period.94 Yet a review of the records indicate that Forest Service officials paid scant attention to the national monuments they administered. In 1916 the minutes of the Service Committee (Washington office staff) included this reference to a report compiled by a Forest Service employee:

The Service did not take the advice, however, and did not, apparently develop any standards or regulations governing the monuments beyond those developed jointly by the Secretaries of Agriculture, War, and Interior in 1906.96 Other than a simple listing, neither the annual reports of the Secretary of Agriculture nor the Forester during the period contain any references to the monuments. No single office in Washington, D.C., was charged with the responsibility of administering the national monuments. Rather, each monument was administered separately on the local level as part of the larger forest unit in which it was located.97 No separate appropriations were made for the monuments, and they received only minor part-time supervision.98 That supervision of the national monuments was not more than a minor undertaking by the Forest Service was indicated in statements regarding Executive Order 6166 in 1933. Transfer of the monuments would not be economical, said R.Y. Stuart, because

D. Military Park System to 1933 The Secretary of War, in addition, had jurisdiction over ten national monuments that had been set aside on military reservations. Five of these were military sites--Big Hole Battlefield, Montana (June 23, 1910); Fort Marion, Florida (October 15, 1924); Fort Matanzas, Florida (October 15, 1924); Fort Pulaski, Georgia (October 15, 1924); and Castle Pinckney, South Carolina (October 15, 1924). The rest were of a non-military nature: Cabrillo, California (October 14, 1913); Mound City, Ohio (March 2, 1923); Statue of Liberty, New York (October 15, 1924); Meriwether Lewis, Tennessee (February 6, 1925); and Father Millet Cross, New York (September 5, 1925). It is interesting to note that, of the ten monuments, only two were in the West, one was in the mid-West, and seven were in the East.100 Beginning on August 19, 1890, moreover, with the establishment of Chickamauga-Chattanooga National Military Park, the secretary's jurisdiction was extended over what came to be, in effect, a national military park system.101 By 1933 this system, which was primarily in the East, consisted of four different types of units--eleven national military parks, twelve national battlefield sites, two national parks, and three miscellaneous monuments:102

According to the 1931 revised regulations for all sites under the jurisdiction of the War Department, the Office of the Quartermaster General in Washington had "charge of national military parks and national monuments and records pertaining thereto."107 Since the previous year, general administrative responsibility for a particular site belonged to the corps commander of the area in which it was located.108 On the site level, supervision was in the hands of a superintendent who, in the case of military sites, at least, had a military background and was able to demonstrate a passing knowledge of military history.109 In practice, however, administration of parks and monuments was much less orderly than it appeared to be on paper. At the Washington level, apparently, one or two part-time clerks in the Quartermaster General's office were assigned to oversee the "non-military function" (parks and monuments) along with their other duties.110 Actual administrative responsibility was divided between several offices. For a period, the district engineers were assigned responsibility for recommending establishment of national monuments.111 After 1926 the Adjutant General's office, through the Army War College, recommended the level of memorialization at the various areas.112 In the case of Chickamauga-Chattanooga, Shiloh, Gettysburg, and Vicksburg, separate commissions, responsible to the Secretary of War, were effective administrators into the 1920s.113 From the perspective of the National Park Service, the War Department's administration of its parks and monuments was inadequate. It had not resulted in proper protection of the areas, nor had the War Department made an effort to develop an adequate program for the visiting public. The department had produced no literature to help visitors, and the paid guides that were available generally had little expertise.114 The 1931 War Department Regulations for military parks and monuments indicated that the areas were set aside to provide "inspirational value to future generations," and to provide visitors with the opportunity to study the actions that had taken place there.115 The latter was not interpreted to mean the casual visitor, however. The primary purpose behind establishment of military parks--and this was indicated in legislation, and repeated over and over again by professionals in the department and by Congressional supporters--was to set aside those areas that would serve as outdoor textbooks in strategy and battle tactics for serious students of military science.116 As such, the battlefields were to be maintained as nearly as possible as they were when the battles were fought. An examination of the available records indicates that while under the jurisdiction of the War Department, the battlefields fulfilled this function. E. National Capital Parks One final group of parks, memorials, and monuments that would come into the National Park System under Executive Order 6166 was the National Capital Parks system in Washington, D.C.117 With its origin in the 1790 act establishing the City of Washington, the National Capital Parks would become the oldest part of the system.118 The National Capital Parks included such sites as Washington Monument; Lincoln Memorial; Rock Creek Park; George Washington Memorial Parkway; sixty miscellaneous structures, memorials, and monuments scattered around the capital; Curtis-Lee Mansion in Virginia; and Fort Washington in Maryland.119 Beginning in 1925, administrative responsibility for the National Capital Parks was lodged in the Office of Public Buildings and Public Parks of the National Capital, whose director was responsible to the president.120 The director had other duties. He was responsible for maintaining and caring for all public buildings in the city, including the White House.121 With the growth of the city, moreover, he had become a member and disbursing officer for a number of commissions established to facilitate completion of projects: Arlington Memorial Bridge Commission, Rock Creek and Potomac Park Commission, National Park and Planning Commission, Zoning Commission of the District of Columbia, National Memorial Commission, Lincoln Memorial Commission, Ericsson Memorial Commission, and Public Buildings Commission.122 From the first decade of the twentieth century, a growing number of the nation's preservationists/conservationists believed that the fragmentation of administration authority over the federal government's parks and monuments was neither economical nor effective in providing the proper protection for the areas set aside. After 1916 many of those individuals, although certainly not all, concluded that administration of the parks and monuments should be unified in the new park bureau. What followed was a seventeen-year-long campaign to unify administration of federal parks and monuments, that when successful in the reorganization of 1933, would transform the National Park Service. Chapter Two: Reorganization of Park Administration Introduction On June 10, 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 6166 which, among other things, combined "all functions of public buildings, national monuments, and national cemeteries" in an Office of National Parks, Buildings, and Reservations--the renamed National Park Service. Far-reaching as this action proved to be for the National Park Service, it was not a radical innovation on Roosevelt's part. Rather, it was the culmination of a campaign to consolidate administration of all federal parks and monuments that began in the first decades of the 20th century. The Antiquities Act of 1906 left administration of the national monuments divided among the Departments of Interior, War, and Agriculture. Almost from the passage of the act, the nation's preservationists/conservationists recognized that such a fragmentation of authority was both uneconomical and inefficient. One of the first to address the problem within the government was Frank Bond, chief clerk of the General Land office. Speaking at the National Park Conference in 1911, Bond detailed the failures of the system as it existed, and concluded that

Almost five years later, H.R. 15522, introduced by Congressman William Kent of California, addressed the problem outlined by Frank Bond in 1911. Section 2 of his bill to create a National Park Service provided

A. The National Park Service and Forest Service The Forest Service opposed any attempt to transfer the national monuments under its jurisdiction, however. It marshaled its powerful lobby in opposition to Section 2, and managed to defeat it.3 The act that established the National Park Service did not include provisions transferring the national monuments from the War and Agriculture departments to the new bureau. The conflict over passage of the enabling act, and the effort to secure transfer of the monuments administered by the Agriculture Department, however, left a residue of bitterness that contributed to the continued friction that characterized relations between the Forest Service and National Park Service in the 1920s and 1930s. This friction was not merely bureaucratic wrangling between two highly aggressive bureaus, but was often, as described by the Forest Service's chief forester in 1921, "continued warfare."4 In public, at least, officials from both bureaus dismissed the notion of a conflict, insisting that the work of the two was complementary and their relationship harmonious. It is true that examples of cooperation between the two bureaus through the years are plentiful. Yet, each viewed the other warily, convinced that the other was working to absorb it. These concerns were, in fact, not unjustified. As early as 1906 and 1907, for example, Gifford Pinchot, then Chief Forester, had actively worked to transfer the national parks from Interior to the Forest Service.5 After the creation of the National Park Service, through the 1920s and into the 1930s, Forest Service and Department of Agriculture officials consistently argued that the National Park Service should be transferred to the Department of Agriculture.6 A clear assumption in this argument was that once transferred, the Park Service would be merged into the Forest Service. In 1923-24, 1928-29, and 1932-33, efforts to effect such a transfer would be made.7 Just as National Park Service officials worried that their agency would be absorbed by the Forest Service, officials in that agency were convinced that Park Service people were working behind the scene to transfer the Forest Service to the Interior Department. Efforts to consolidate administration over parks and monuments in the 1920s specifically referred only to transfer of sites administered by the War Department areas to the National Park Service. Forest Service officials clearly believed, however, that such a transfer would be merely a first step that would ultimately lead to transfer of all national monuments to the Park Service. Particularly after 1922, when Interior Secretary Albert Fall proposed transferring the national forests to the Interior Department, Forest Service officials viewed almost all National Park Service actions, and that included boundary adjustments, with considerable suspicion, if not hostility.8 B. Early Efforts to Transfer War Department Parks With passage of the National Park Service enabling act in 1916, a new personality emerged as a leader in the campaign to consolidate administration of the parks and monuments. More than anyone else, it was Horace Albright who kept the movement alive for seventeen years, and it was his political acumen that was largely responsible for the final success in 1933. Under Albright's leadership, the focus of the campaign shifted. As indicated, before 1916 efforts had been directed largely toward consolidating administration of the national monuments under one agency. Albright, on the other hand, would be concerned primarily with transferring the national military parks and battlefields under the jurisdiction of the War Department to the National Park Service. The new emphasis reflected Albright's long-standing interest in history. He argued, too, that coordination of the administration of those areas would assist in capturing American tourists who would spend their money at home, rather than in Europe, now that the great war was over.9 More important than either of these, however, was Albright's belief that such a transfer was necessary to insure the continued independence of the National Park Service. Almost all the War Department's areas were east of the Mississippi River, while Park Service areas were confined without exception to the western states Absorption of the military parks would allow the Service to extend its influence nationwide, and to build a national, not regional constituency. Such a national constituency would effectively guarantee that the National Park Service would not be absorbed by another federal agency.10 Albright lost no time, once passage of the National Park Service enabling act was assured and the organization was in place, in undertaking a publicity campaign aimed at securing transfer of the military parks. In the first annual report of the director of the National Park Service, Albright outlined his views in a section entitled, "National Parks in the War Department, Too:"

Each succeeding annual report included some similar statement.12 At the same time, Mather and Albright began to lobby with their counterparts in the War Department as well as with influential members of Congress. In August 1919, for example, Albright reported to Mather that he had been able to convince Senator Kenneth D. McKeller of Tennessee to support the principle of transfer of the military parks.13 The campaign carried on by Park Service officials was paralleled outside the government. As had been the case in the campaign to secure passage of the National Park Service enabling act, leadership here was provided by Horace J. McFarland, president of the American Civic Association. Never one to mince words, McFarland declared:

The first viable opportunity to effect a transfer of the War Department parks and monuments came on December 17, 1920, when the two houses of Congress established a joint committee to study a general reorganization of the executive departments.15 Nearly three years later, on February 13, 1923, President Warren G. Harding outlined the major reorganization proposals recommended by his cabinet. Along with such recommendations as the coordination of military and naval establishments under a Department of National Defense and a new Department of Education and Welfare was the transfer of nine national military parks to the Department of the Interior.16 The last recommendation had been prepared by Park Service officials and transmitted by Secretary of the Interior Albert B. Fall.17 Officials in the War Department generally supported the Park Service's efforts to effect the transfer of areas under their jurisdiction, largely because they were concerned over the expense generated in their administration. Secretary of War John W. Weeks testified in favor of the proposed transfer before the Joint Committee on Reorganization. While admitting under sharp questioning by the committee that there may have been cases where a battlefield should remain under the jurisdiction of the War Department, Weeks nevertheless was firm in his opinion that "the entire park system should be under one control."18 Members of the committee expressed skepticism at Weeks' assertion, however. Of particular concern, as evidenced by the questions they asked, was the apparent difficulty in clearly separating the military parks from military cemeteries. Transfer of the military parks to the Department of the Interior, they quite clearly believed, would inevitably lead to civilian control over military cemeteries.19 Whether as a result of this concern, or whether as Horace Albright later wrote, the proposal "got lost in the shuffle," transfer of the national military parks to the Department of the Interior was not included in the report issued by the Joint Committee on Reorganization.20 While the National Park Service hoped to use the general reorganization of the executive departments as a means of acquiring the national military parks, Secretary of Agriculture Henry C. Wallace advanced another proposal. In testimony before the joint committee, Wallace asserted that administration of the public domain, and that included the national parks and all national monuments, should be solely the responsibility of the Department of Agriculture.21 Wallace admitted that he was not prepared to say whether any economy would result from his proposal. Nevertheless, he argued that many of the problems facing the parks and forests were similar, and "as far as the parks are concerned, it would be practicable."22 Senator Reed Smoot of Utah, a long-time friend of the National Park Service, observed that any reorganization plan that proposed transfer of the national parks to the Department of Agriculture would not pass. With that observation, Secretary Wallace's suggestion died.23 Failure to secure transfer of the national military parks as part of a general reorganization of executive departments did not long deter Park Service officials. After 1924, according to Horace Albright, he and Mather worked hard to insure that a proposal calling for transfer of the national military parks would be a part of the program developed by President Calvin Coolidge's National Conference on Outdoor Recreation.24 Secretary of War Weeks resigned on October 12, 1925. Albright, Mather, and the new Secretary of the Interior, Hubert Work, immediately contacted his successor, Dwight F. Davis, to resume inter-departmental talks regarding transfer of the military parks.25 Despite some growing opposition at the lower echelons of his department, Davis was swayed by their arguments, and indicated that he would support another attempt to transfer the military parks. On April 20, 1928, a bill that had been drafted jointly by Interior and War Department staffs was sent to Congress, along with a letter signed by the two secretaries.26 Introduced by Senator Gerald P. Nye of North Dakota, Chairman of the Committee on Public Lands, S. 4173 went further than previous efforts, proposing to transfer all military parks, national parks, and national monuments from the War Department to the Department of the Interior.27 In addition, the bill provided for the transfer, as well, of all civilian employees and unexpended appropriations.28 Of particular interest, because it was apparently the first time the term was used, the bill provided for a new unit in the Park System--the National Historical Park.29 It is quite probable that this term reflected the direction of Horace Albright's thinking. Senator Nye's committee supported the proposal and reported it to the full Senate within two weeks, on May 3, 1928.30 In the House, however, the reception was quite different. Hearings were not held until the following winter.31 Although the bill was originally sent to the Committee on Public Lands where it would have been received more favorably, hearings were held before John M. Morin's Committee on Military Affairs. Horace Albright later wrote that the committee "was mildly hostile . . ., or at least the members present were not favorably disposed."32 Had the secretaries of War and Interior appeared before the committee in person, he continued, the result might have been different.33 An examination of the record of the hearings, however, suggests that in this case, the normally realistic Albright cast events in a too-favorable light. Congressmen Otis Bland, E.L. Davis, and S.D. McReynolds all either wrote letters or testified against the bill. Congressman Bland said that transfer of the military parks made "as much sense . . . as putting military instruction in a medical school," and Congressman McReynolds speculated that the National Park Service would "put yellow buses and [hot-dog] stands throughout . . . ."34 Clearly these congressmen and those on the committee believed that the purpose of areas administered by the two agencies was so different--the War Department areas for military instruction and memorialization while the National Park Service's areas were "pleasuring grounds"--that one agency could not possibly be equipped to deal with both.35 As had been the case in 1924, both the congressmen who testified against the bill and committee members were particularly concerned that the transfer would lead to civilian control of military cemeteries.36 Horace Albright, who was by now the Director of the National Park Service, and Charles B. Robbins, Assistant Secretary of War, testified as best they could under sometimes almost sarcastic questioning. They could not, however, overcome the opposition of the committee. The tone of the hearings was a clear signal of the outcome, and, as expected, the committee took no action. Albright did attempt to secure another hearing, but when that failed the bill died in committee.37 Disappointed as he must have been over the failure of the House committee to act on S. 4173, Horace Albright was not one to long nurse his bruises. In March 1929, a new president, Herbert C. Hoover, was inaugurated. Within weeks Albright initiated discussions regarding transfer of War Department areas with the new secretaries of War and Interior, John W. Good and Ray L. Wilbur.38 Both men, who were old acquaintances of Albright's, proved receptive to the idea. Wilbur further indicated that President Hoover intended to seek authority from Congress for a general reorganization of the executive departments. He assured Albright that any reorganization would include transferring "historic sites from other agencies" to the National Park Service.39 President Hoover, himself, obviously intended to transfer the national monuments from the War and Agriculture Departments to the National Park Service. On May 15, 1929, he wrote his Attorney General William D. Mitchell, requesting his opinion as to whether such an action could be taken without specific legislative authority.40 On July 8, 1929, Mitchell replied that in his opinion, such an action would infringe on the constitutional prerogatives of Congress, and would be illegal in the absence of legislation to that effect.41 Meanwhile, work on a general reorganization of the executive continued. In October 1929 Secretary Wilbur sent an Interior Department plan to an interdepartmental coordinating committee created to evaluate such proposals. Included in Wilbur's reorganization plan was a request to transfer "historic sites and structures in other departments, especially the War Department" to the National Park Service.42 A new element was added to the proposed transfer when Wilbur requested that the parks and buildings in Washington, D.C., also be transferred to the National Park Service.43 From time to time, over the next several years, President Hoover sent messages to Congress regarding reorganization of the executive branch. It was not until June 1932, however, that Congress finally provided him with the specific authority he needed to proceed.44 On December 9, 1932, one month after he had been defeated at the polls, President Hoover submitted a general reorganization proposal to Congress, as required. Included were some, but not all, elements of the Interior Department's reorganization plan submitted three years earlier. The proposal would have created a number of divisions within Interior. Among those agencies grouped under a Division of Education, Health and Recreation, were the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Public Health Service, Division of Vital Statistics, and National Park Service.45 As Park Service officials hoped it would, the plan would have transferred the national parks, monuments, and certain national cemeteries in the War Department to the National Park Service.46 Although Secretary Wilbur had proposed transferring the National Capital Parks, the Office of Public Buildings and Parks, which administered those parks, would have been transferred from its position as an independent agency to the proposed Division of Public Works in the Interior Department.47 From the first days of the Hoover administration it had been anticipated, apparently, that President Hoover's proposed reorganization proposal would provide for the transfer of the Forest Service to the Department of the Interior, or possibly for the establishment of a Conservation Department which would combine all federal land-use agencies.48 Former Representative Louis Cramton, who now served as a special attorney on the staff of Secretary Wilbur, proposed the former, while President Hoover had noted the wisdom of the latter in a December 3, 1929, message to Congress.49 Both proposals were highly controversial, and either would have raised considerable opposition both in Congress and outside the government. The decision not to include either in a general reorganization proposal was certainly a wise one. The legislation that provided President Hoover with the authority to reorganize the executive branch included a provision requiring that the proposals be forwarded to Congress for sixty days before becoming effective.50 Congress rarely has been willing to give much cooperation to a lame-duck president, particularly when one was as thoroughly repudiated by the voters as Herbert Hoover was in 1932. It should not have been surprising to anyone that a broad-ranging reorganization such as the one he proposed would not be approved. Earlier in the year, another bill, H. R. 8502, introduced by Representative Ross A. Collins of Mississippi, provided for transfer of the War Department parks and monuments to the Department of the Interior.51 The bill, which was nearly identical to S. 4173, introduced by Senator Nye in 1927, was drafted by the Interior Department staff at Congressman Collins' request.52 The National Park Service prepared a favorable report on the bill, and in a January 28, 1932, letter to the Secretary of War, Interior Secretary Wilbur reaffirmed his support of the proposal.53 Hearings were never held on the bill, however, quite possibly because of the anticipated reorganization of the executive branch.54 While President Hoover's reorganization proposal was before Congress, another bill, this one proposing transfer of the Forest Service to the Department of the Interior was before the House Agricultural Committee.55 H.R. 13857, introduced by Representative Eaton, was apparently never given serious consideration. C. Reorganization of 1933 The change in administrations in March 1933 posed potentially serious problems for the National Park Service's campaign to unify administration of all national parks and monuments. From the beginning the Service had stood above partisan politics. Despite the fact that he diligently sought to preserve that tradition, Horace Albright had become identified closely enough with the Hoover administration that he harbored some concern that he would be replaced by the incoming administration.56 Harold L. Ickes, President Roosevelt's choice as Secretary of the Interior, asked Albright to stay on, however. Within a short time, Albright would emerge as a close and influential advisor to the irascible Secretary of the Interior.57 Albright lost no time, once it was clear his job was secure, in approaching Ickes regarding transfer of the military parks. Within days after Ickes had taken office and begun to settle in his new job, Albright had won his approval of the proposal.58 In the first hectic week of the New Deal, moreover, Albright had met with and secured the approbation of George Dern, the new Secretary of War.59 More importantly, because of the close relationship developed with Ickes, Albright soon found himself in a position to present his case at length with the one man who could guarantee its success--Franklin D. Roosevelt. On April 9, 1933, Albright was among the invited guests on an excursion to former President Hoover s camp on the Rapidan River in nearby Virginia.260">60 As they prepared to return to Washington, Roosevelt asked Albright to ride along in his touring car. Never one to be reticent, or to miss an opportunity, Albright used a discussion of Civil War battles to press his case for transfer of the War Department parks. Roosevelt had decided to reorganize the executive branch within weeks of his inauguration.61 In what must have almost been an anticlimax to some sixteen years of effort, Roosevelt asked no questions, but merely agreed that it should be done, and told Albright to present the proper material to Lewis Douglas, chief of staff for reorganization activities.62 Some anxious moments followed. In early 1933 Gifford Pinchot, who was a long-time acquaintance of Franklin D. Roosevelt, and others had revived efforts to transfer the National Park Service to the Department of Agriculture, where it would be merged with the Forest Service. 63 In mid-April, both Albright and Ickes heard rumors that suggested Albright had seriously misinterpreted the president in their April 9 discussion regarding reorganization--that reorganization in the Roosevelt administration would result in transfer of the National Park Service to the Department of Agriculture.64 An early May meeting with Lewis Douglas reassured Albright, however, and the NPS director promptly submitted his proposals for transfer of the War Department parks and monuments.65 The proposals Albright submitted to the reorganization committee were modest--the same, essentially, that the National Park Service had been supporting since 1916.66 He certainly was not prepared for the scope of the proclamation that emerged. Executive Order 6166, issued on June 10, 1933, and effective sixty days later, dealt with a wide range of agencies and functions--procurement investigations, statistics of cities, insular counts, and Internal Revenue were only a few of the subjects addressed. Section 2 spoke directly to the National Park Service:

Not only would the Park Service inherit the War Department parks and monuments as Albright had proposed, but also all national monuments within the continental United States, the national monuments administered by the Forest Service, the parks, monuments, and public buildings in the District of Columbia, and some elsewhere in the country,68 the Fine Arts Commission, and the National Capital Park and Planning Commission. Especially galling to Park Service employees, was the provision in Executive Order 6166 that changed the name of the National Park Service to the Office of National Parks, Buildings, and Reservations.69 Albright had seen a draft of the proposed executive order at a second meeting with Lewis Douglas in May.70 In the face of Douglas's growing impatience, he argued that Arlington and other national cemeteries still open for burial should remain under the jurisdiction of the War Department, that only those buildings that were clearly monumental in character--the White House, Washington Monument, and Lincoln Memorial, for example--should be transferred, that the Fine Arts Commission and National Capital Park and Planning Commission should remain independent, and that the name, "National Park Service," should be retained.71 After consulting with Ickes and Frederic A. Delano, however, Albright decided further opposition to the proposal would jeopardize all that he had worked for.72 The wisest course of action would be to accept the proposal as drafted, and work to reverse these elements that he considered objectionable after the president issued the order. For the next month, Albright did just that. On July 28, largely as a result of his well-orchestrated campaign, President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 6228, an order that clarified Section 2 of Executive Order 6166, "postponing until further order," transfer of Arlington and other cemeteries still open for burial, while leaving the cemeteries associated with historical areas in the soon-to-be Office of National Parks, Buildings, and Reservations.73 In addition, Albright was able to secure separation of the National Capital Park and Planning Commission and Fine Arts Commission, save for some administrative functions.74 He saw no immediate chance of restoring the name, however, and decided to postpone that battle to a later date. It was not until March 10, 1934, that his successor, Arno B. Cammerer, was able to announce that the old name had been restored.75 Writing about the events leading up to the reorganization of 1933 some years later, Horace Albright said that when he first saw a draft of Executive Order 6166, he "was stunned by its scope."76 He was most certainly not the only person in Washington that reacted that way. Particularly surprising to Park Service officials must have been the reaction of the War Department. Since the early 1920s, successive Secretaries of War had registered support for transfer of War Department parks and monuments to Interior, and had testified so before Congressional committees. In February 1932 Patrick Hurley had reaffirmed that position, and Albright had secured George Dern's approval in March 1933.77 After June 10, 1933, however, it became evident that sentiment for transferring the parks and monuments came more from political appointees who headed the War Department than from professional officers there. Perhaps the most vocal opponent of transferring the War Department areas was Colonel Howard E. Landers, who, according to Verne Chatelain, fought it "tooth and nail."78 Since the 1920s, Colonel Landers had been responsible for investigating battlefields for commemorative purposes, and as such was more knowledgeable than anyone else with the War Department's administration of military parks and battlefields. He was a frequent critic of the War Department's administration, particularly in what be believed to have been the failure to properly use the data he collected.79 His criticism may have been misinterpreted by Park Service officials, for whatever feelings Colonel Landers had regarding use of his material, he had never favored transfer of military parks to the Interior Department.80 According to Dr. Chatelain, Colonel Landers felt strongly enough to send a memorandum to President Roosevelt in an effort to prevent transfer after June 10, 1933.81 Colonel Landers was the most vocal opponent, but he was not the only person in the War Department who expressed misgivings once transfer became fact. There is no question that these misgivings were raised to a large extent because of the inclusion of the national cemeteries in the transfer order. In general, though, the impression that emerges from Park Service records is that despite years of official approbation of the principle of transfer, the War Department's attitude was one of reluctance that sometimes bordered on resistance or non-cooperation, once that transfer was ordered. This attitude was not confined to the military professionals in the department. On June 21, 1933, Harry Woodring, Acting Secretary of War, wrote to President Roosevelt to request that all military cemeteries, including those on or adjacent to the military parks and battlefields, be excluded in the executive order. They were all, he wrote, military in nature, and the Department of the Interior could not possibly "be as interested in the proper maintenance of these cemeteries as the War Department."82 The next day Woodring sent another letter to the president, this time to request postponement of the effective date of Executive Order 6166 until all plans for improvements at the various areas--and he indicated these were extensive--were accomplished, and work on the establishment of Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania, Petersburg, and King's Mountain was completed.83 In closing Woodring seemingly took a position that would have pleased even the most vociferous opponent of transfer: