|

GLACIER

Glaciers and Glaciation in Glacier National Park Special Bulletin No. 2 |

|

GLACIERS OF GLACIER NATIONAL PARK

Within the boundaries of Glacier National Park there are 50 to 60 glaciers, of which only two have surface areas of about one-half square mile, and not more than seven others exceed one-fourth square mile in area.

All these bodies of ice lie in shaded locations on the east- or north-facing slopes at elevations between 6,000 and 9,000 feet, in all cases well below the regional snowline. Consequently, they owe their origin and existence almost entirely to wind-drifted snow.

Ice within these glaciers moves slowly. The average rate in the smallest ones may be as low as 6 to 8 feet a year, and in the largest probably 25 to 30 feet a year. There is no period of the year when a glacier is motionless, although movement is somewhat slower in winter than in summer. Despite the slowness of its motion the ice, over a period of years, transports large quantities of rock material ultimately to the glacier's end where it is piled up in the form, of a moraine.

|

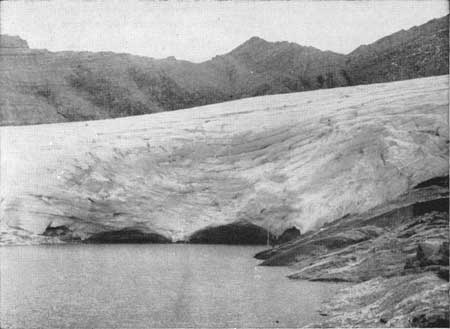

| THE ICE FRONT ON SPERRY GLACIER IS ABOUT 100 FEET HIGH (BEATTY PHOTO) |

Sperry is the largest glacier in the park. Its surface in 1950 was somewhat more than 300 acres. A striking feature of this glacier is the precipitous character of its front, which at one point consists of a sheer cliff from 80 to 100 feet high. Blocks of ice occasionally break from this cliff and go crashing down into a little unnamed lake where they float as bergs throughout the summer months.

|

| JACKSON GLACIER IS VISIBLE FROM GOING-TO-THE-SUN ROAD (BEATTY PHOTO) |

The second largest glacier in the park is Grinnell with a surface area of 280 acres. Both Sperry and Grinnell have probable maximum thicknesses of 400 to 500 feet.

Other important park glaciers, although much smaller than the first two mentioned, are Harrison, Chaney, Sexton, Jackson, Blackfoot, Siyeh, and Ahern. Several others approach some of these in size, but because of isolated locations they are seldom seen. As a matter of fact, there are persons who visit Glacier National Park without seeing a single glacier, while others, although they actually see glaciers, leave the park without realizing they have seen them. This is because the highways afford only distant views of the glaciers, which from a distance appear much like mere accumulations of snow. A notable example is Grinnell as seen from the highway along the shore of Sherburne Lake and from the vicinity of the Many Glacier Entrance Station. The glacier, despite its length of almost a mile, appears merely as a conspicuous white patch high up on the Garden Wall at the head of the valley.

Several of the glaciers, however, are accessible by trail and are annually visited by many hundreds of people, either on foot or by horse. Most accessible of all park glaciers is Grinnell. It can be reached by a six-mile trip over an excellent trail from Many Glacier Hotel or Swiftcurrent Camp. Sperry, likewise, can be reached by trail, although the distance is several miles greater than in the case of Grinnell. The trip, however, can be broken and possibly made more interesting by an overnight stop at Sperry Chalet, which is located about three miles from the glacier. Siyeh is the only other regularly visited park glacier. It lies about half a mile beyond the end of the Cracker Lake trail, and can be reached from that point by an easy walk through grassy meadows and a short climb over a moraine. Siyeh however, is less spectacular than either Grinnell or Sperry, being much smaller and lacking crevasses, so common on the other two. Few people make the spectacular trail trip over Siyeh Pass but those who do may visit Sexton Glacier by making a short detour of less than half a mile where the trail crosses the bench on which the glacier lies. Sexton is a small glacier, but late in the summer after its snow cover has melted off it exhibits many of the features seen on much larger bodies of ice.

|

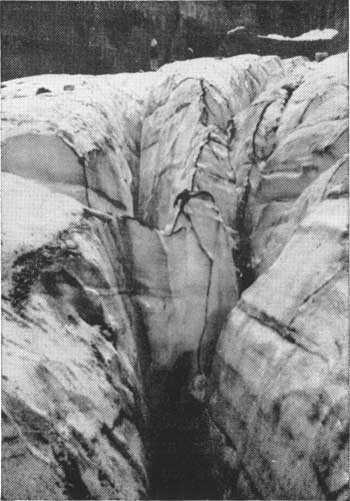

| CREVASSE IN GRINNELL GLACIER (WALKER PHOTO) |

Interesting surface features which can be seen on any of these glaciers include crevasses, moulins (glacier wells), debris cones, and glacier tables. Crevasses are cracks which occur in the ice of all glaciers. They are especially numerous on Sperry and Grinnell. Moulins, or glacier wells, are deep vertical holes which have been formed by a stream of water which originally plunged into a narrow crevasse. Continual flow of the stream enlarges that part of the crevasse, creating a well. Several such features on Sperry Glacier have penetrated to depths of more than 200 feet, and are 20 or more feet wide at the top.

No one can walk over the surface of Grinnell Glacier without noticing a number of conical mounds of fine rock debris. Actually these are cones of ice covered with a veneer, seldom more than two inches thick, of rock debris, so their name, debris cone is somewhat misleading.

The rock material is deposited on the glacier by a stream. After the stream changes its course the debris protects the ice underneath from the sun's rays. As the surface of the glacier, except that insulated by the debris, is lowered by melting, the mounds form and grow gradually higher until the debris slides from them, after which they are speedily reduced to the level of the rest of the surface. They are seldom higher than 3 or 4 feet.

A glacier table is a mound of ice capped, and therefore protected from melting, by a large boulder. Its history is similar to that of the debris cone. After a time the boulder slides off its perch, and then the mound of ice melts away.

Snow which fills crevasses and wells during the winter often melts out from below, leaving thin snowbridges in the early part of the summer. These constitute real hazards to travel on a glacier because the thinner ones are incapable of supporting a person's weight. This is one very good reason why the inexperienced should never venture onto the surface of a glacier without a guide.

It is probable that the park glaciers are not remnants of the large glaciers present during the Ice Age which terminated approximately 10,000 years ago, because it is known that several thousand years after that time the climate of the Glacier National Park region was somewhat drier and warmer than now. Under such conditions glaciers could not have existed.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

glac/gnha/2/sec2.htm

Last Updated: 11-Jul-2008