|

GRAND TETON

Campfire Tales of Jackson Hole |

|

JOHN COLTER

THE DISCOVERY OF JACKSON HOLE AND THE YELLOWSTONE

By MERLIN K. POTTS, Chief Park Naturalist

To John Colter, mountain man, trapper, and lone wanderer in the exploration of the Rocky Mountain wilderness, belongs the distinction of being the first white man to enter Jackson Hole and the "Country of the Yellowstone."

His biographers record that Colter was a descendant of Micajah Coalter, Scotsman, who settled in Virginia about 1700. That John was born in Virginia is not definitely known, but there is no evidence to indicate that any of the Coalters, from John's great-great-grandfather to his own generation, ever lived elsewhere. He was born toward the close of the 18th Century, probably about 1775. There are no records of Colter's early life, other than to indicate emigration to Kentucky with other members of the family before 1803. History marks his first appearance with his enlistment in the Lewis and Clark Expedition of October 15 of that year. He proved to be a skillful hunter, a faithful and reliable employee, popular with his commanders and the other men of the Expedition. He served with Lewis and Clark on the westward journey, and was returning to St. Louis in August 1806 when the party, commanded by Captain Clark, encountered 2 trappers enroute to a winter's sojourn on the upper Missouri. Colter expressed a desire to join these men, and was released from the Expedition to do so. The partnership dissolved in the spring of 1807, after what appears to have been an unsuccessful venture, insofar as peltry was concerned, but undoubtedly rewarding experience wise.

Colter again started for St. Louis, by canoe, down the Missouri. By now he was an experienced hand in unknown country. Moving alone and matching his skills against the hazards and rigors of the land were no more than everyday occurrences. As he swept down the turbid river, swollen by spring flood waters, his intention was to return to the civilization he had left 3 years before. Once again his plans were altered by chance.

A young Spaniard, Manuel Lisa, engaged in the fur trade in St. Louis, and influenced by reports of the abundance of beaver on the upper Missouri, had determined to explore the possibilities of extending his operations in that hitherto unexploited region. Accordingly, he organized a brigade and set forth up river. Colter met the party, and was persuaded by Lisa to join him. Lisa, a shrewd trader, was not a frontiersman. He recognized in Colter exactly the type of man he needed, and quite probably the inducements he offered were considerable. Yet, to a man of Colter's stamp, the financial gain possible was secondary to the prospect of further opportunity for adventure. We can surmise that Lisa experienced little difficulty in influencing the young and venturesome trapper to turn his back again on the doubtful attractions of the settlements.

It was late in November of that year, 1807, before Lisa selected a site for his trading post, at the confluence of the Yellowstone and Big Horn Rivers, in what is now south-central Montana. Construction of the post was begun immediately. Lisa named it Fort Raymond, after his son, but it was more generally known as Manuel's Fort.

It was Lisa's objective, not only to trap, but to engage in trade with the Indians, and to learn as much as possible about the trapping territory to the west. Of his men, Colter was the best suited to seek out the tribesmen, encourage them to trade at the post, and survey the lands with an eye to its productivity in fur. Thus Lisa instructed him, outfitted him, and sent him forth.

It could not have been earlier than late November when Colter set out. His equipment must have been meager; snowshoes, his gun, ammunition, a blanket or robe, and little or no food, since he would have intended to "live off the land" and his pack would likely not have exceeded 30 pounds, including "geegaws" for the Indians he encountered.

His exact route has long been a matter for conjecture among historians. He was to venture into country unknown to any other than the Indians, he carried no maps, he followed what must have appeared to him to be the route of least resistance, insofar as he could judge the terrain he traversed. He, from force of circumstance, must have followed the watercourses and game trails, sought the lowest mountain passes he could find, pursuing a devious course which led him to the south and west.

In the light of Colter's own later attempt to trace his route for Captain Clark, and through our knowledge of today's maps, it can be assumed, with a fair degree of reliability, that he moved across country to Pryor's Fork, up that stream and down Gap Creek to its junction with the Big Horn, thence up the Big Horn to the Shoshone (Stinking Water). He followed the course of the Shoshone upstream to the vicinity of what is now Cody, Wyoming, and along the base of the Absaroka Mountains into the Wind River Valley, striking the Wind probably some distance south and east of present day Dubois.

It appears that it was on the Stinking Water that Colter discovered the area which his contemporaries of the trapping fraternity derisively named "Colter's Hell," after Colter's description of the thermal features there. Historians writing many years later, perhaps more romantically than accurately, attributed Colter's reference to one or more of the now famous geyser and hot springs sections of the Yellowstone. It makes a better story thus, but the preponderance of evidence from the accounts of the trappers themselves places "Colter's Hell" in the vicinity of the DeMaris Springs, near Cody. Geological indications are that the area was much more active, insofar as thermal phenomena are concerned, then than now.

Two excellent early authorities confirm this location of "Colter's Hell." As set forth in Burton Harris' John Colter, His Years in the Rockies:

As late as 1848, the accomplished Belgian priest, Father DeSmet, placed Colter's Hell on the Stinking Water on the strength of information obtained from the few trappers who were left in the mountains at that date. The courageous priest, known as "Black Robe" to the Indians, was on his way to visit the Sioux in 1848 when he wrote the following account: "Near the source of the River Puante (Stinking Water, now called Shoshone) which empties into the Big Horn, and the sulphurous waters of which have probably the same medicinal qualities as the celebrated Blue Lick Springs of Kentucky, is a place called Colter's Hell—from a beaver hunter of that name. This locality is often agitated with subterranean fires. The sulphurous gases which escape in great volumes from the burning soil infect the atmosphere for several miles, and render the earth so barren that even the wild wormwood cannot grow on it. The beaver hunters have assured me that the frequent underground noises and explosions are frightful."

Washington Irving, in The Rocky Mountains (1837) says:

The Crow country has other natural curiosities, which are held in superstitious awe by the Indians, and considered great marvels by the trappers. Such is the Burning Mountain, on Powder River, abounding with anthracite coal. Here the earth is hot and cracked; in many places emitting smoke and sulphurous vapors, as if covering concealed fires. A volcanic tract of similar character is found on Stinking River, one of the tributaries of the Big Horn, which takes its unhappy name from the odor derived from sulphurous springs and streams. This last mentioned place was first discovered by Colter, a hunter belonging to Lewis and Clark's exploring party, who came upon it in the course of his lonely wanderings, and gave such an account of its gloomy terrors, its hidden fires, smoking pits, noxious streams, and the all-pervading "smell of brimstone," that it received, and has ever since retained among the trappers, the name of "Colter's Hell!"

Upon reaching the valley of the Wind, it would have been logical for Colter's route to have been north and west over the Wind River Mountains through Union Pass, the easiest available, at an elevation of 9,210 feet. Here historians have indulged in a long standing, and unresolvable debate, some authorities contending that he would probably have followed up the Little Wind River, crossing the Wind River Mountains further north, at Togwotee Pass. Whichever route he used to the westward—Union Pass and the Gros Ventre River drainage, or Togwotee Pass and Blackrock Creek—either brought him into Jackson Hole.

There can be little doubt that in any event his course was a circuitous one, following the twistings and turnings of many water courses, deviating along Indian trails to the winter encampments of the Crows, attentive to his instructions from Manuel Lisa. Quite probably the friendly Crows aided Colter by directing him to routes of easy passage, perhaps accompanying him over parts of his journey, though history makes no mention of this.

Entering Jackson Hole on its eastern margin, Colter saw before him a scene of unsurpassed grandeur. At this season, which must have been well into December, the floor of the Hole presented a broad expanse of snow-blanketed valley, broken only by the forested buttes, looming black against the glistening white, and the timbered water courses, marked by cottonwood, willow, and spruce. No smoke of Indian village lifted above thickets. The tribesmen had moved to areas of less rigorous climate, east, south, or west, weeks before. The soaring peaks, lifting their gleaming spires across the valley, their canyons deep shadowed in blue gloom, stretched for miles to the north and south. Even his stout heart must have faltered, at least momentarily, at the grim barrier ahead.

Other than the Snake River Canyon, a route which he could hardly have anticipated from any vantage point, he would logically have selected Teton Pass as the most feasible crossing of the Teton Range to the southwest. Here the historians, at least those who accept the theory of a trans-Teton route, are in almost unanimous agreement, although some would have us believe that he made a frontal assault through Cascade Canyon. This hardly seems likely, since Colter, bold as he was, evidenced no characteristics of the foolhardy, and to his eyes the Cascade Canyon route could scarcely have appeared to offer a feasible crossing.

One cannot but puzzle a bit, however, as to his reason for crossing the Range at all. From the broad valley of the Hole the route northward up the Snake River into the Yellowstone was to any eye an easy one. The terrain sloped gently, there were no mountain walls to scale or circle, nothing to indicate any obstacle of consequence. Indeed, many notable historical scholars have opposed the Teton Pass theory, asserting that he did avoid the Tetons by moving northward. He would certainly have fulfilled Lisa's orders to contact nearby Indian tribes by the time he had reached Jackson Hole.

Accepting the Teton route, as we must in the light of later evidence, we add further stature to Colter's perseverance and venturesome spirit. He went over the mountains, perhaps because the Indians had described the route and country beyond to him, perhaps because he was seeking the reported "Spanish Settlements" on the headwaters of the Colorado River (Green River), or perhaps for the very simple reason that he wanted to see what was on the other side.

At any rate, the Idaho side of the Range has given us the first really tangible clue as to Colter's whereabouts while on his winter journey. In 1930, about 4 miles east of the Idaho village of Tetonia, was found the "Colter Stone."

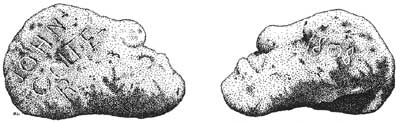

In the spring of that year, while plowing virgin land on his father's homestead, William Richard Beard, then a boy of 16, unearthed the stone from its resting place about 18 inches beneath the surface. His attention was first attracted by the shape of the rock. It had been roughly formed to resemble a human head, flattened, but with the unmistakeable outline of forehead, nose, lips, and chin. When the stone had been cleaned, it was found to have been crudely carved. One side bore the name "JOHN COLTER," the other was inscribed with the almost illegible figures, "1808."

|

| The "Colter Stone," with Colter's name inscribed on one face, the barely legible date 1808 on the other. Found near Tetonia, Idaho, in 1930, the stone is now on display in the History Museum exhibits at the Moose Visitor Center, Park Headquarters, Grand Teton National Park. |

The slab of gray, rhyolite lava from which the stone was shaped is soft and easily worked. It would have taken no great amount of labor to have accomplished the job. Perhaps it provided a means of passing time while Colter was blizzard-bound, or merely loafing in camp, taking a well-earned respite from days of arduous travel.

Immediately after the stone was given to the National Park Service in 1933 by Mr. Aubrey C. Lyon, who had acquired it from the Beards, a controversy developed as to its authenticity. The carving of stones and tree trunks by early trappers and explorers was a well-established practice; several such evidences of their passing have been found. There have been hoaxes revealed also, and there were those who refused to accept the Colter Stone as valid. The evidence, what little there was to investigate, was carefully analyzed. There was no duplicity remotely connected with the finding of the stone. The Beards had never heard of John Colter. It had rested at a depth of some several inches beneath the earth's surface. Certainly Colter would not have carved it, then buried it, so the accumulation of soil above the stone must have been the result of some years, and the stone had weathered before burial, it could hardly have weathered after being covered by earth. In the final analysis, it seems most illogical that anyone mischievously inclined would have been sufficiently informed to perpetrate a hoax at such a remote spot. A prankster would have deposited his bogus relic in a place where he could reasonably expect its ready discovery. Else why bother?

The stone now reposes in the History Museum at Park Headquarters, Grand Teton National Park, as mute evidence that Colter did indeed "pass this way."

Colter's route, from the discovery of "his" stone, appears to have led northward along the base of the western side of the Teton Range, until he perceived the next comparatively easy route for a return toward the east. Recrossing the Tetons he struck the western shore of Yellowstone Lake, called "Lake Eustis" on William Clark's "Map of the West," published in 1814. Tracing the route outlined on this inaccurate map, historical scholars propound that he followed the Yellowstone River to a crossing near Tower Falls, up the Lamar River and Soda Butte Creek, and back across the Absaroka Range. By way then of Clark's Fork and Pryor's Fork he made his way back to Manuel's Fort, arriving early in 1808.

So ended a most remarkable tour of some 500 miles, most of it made during the winter months. Aside from the rigors of winter climate, foot travel, on snowshoes, must have proved easier, with underbrush buried beneath the snow, than hiking in summer over the same route.

That Colter made the journey, that he did traverse, in one way or another, Jackson Hole and the Yellowstone Park area, has been challenged by few historians, though all concede that his exact route will forever be a matter for speculation. The unprovable can hardly be proven.

Though Colter has not been celebrated in history as have other famous "Mountain Men" of a few years later, notably Jim Bridger, Bill Sublette, Joe Meek, and Jedediah Smith, to name a few, he remained a notable figure among his fellows until 1810.

It was in the spring or summer of 1808, following his return to Lisa's post, that Colter had his first encounter with the Blackfeet. It was the custom of these fierce and warlike Indians to send war parties south and west on forays into the lands of their enemies, the Crows and other tribes. They were not, however, particularly hostile to the whites, at least at this time.

Colter had again been dispatched by Lisa to "drum up" trade with the Indians. While traveling with a large party of Flatheads and Crows, near the Three Forks of the Missouri, Colter's band was attacked by a Blackfoot war party. In the battle that ensued Colter was wounded, the Blackfeet were driven off, and the crippled Colter eventually managed to make his way back to Manuel's Fort. The Blackfeet were enraged by the presence of a white man, however accidental it may have been, fighting on the side of their traditional enemies. Colter's participation was apparently the inspiration for the hostility of the Blackfeet toward the whites that followed, and quite probably their hatred of Colter himself, which led to his most famous adventure.

Every school boy has read accounts of Colter's famous "run." Early writers made much of it, various versions have appeared in print, all essentially similar. Summarized briefly the records indicate that Colter, in the company of one John Potts, returned again in 1808 to the Three Forks country. Again he and his companion had a "run in" with the Blackfeet. Surprised while setting their traps, Colter was taken prisoner. Potts made the mistake of resistance against overwhelming odds and was promptly riddled with arrows and bullets after shooting one of the Indians. Colter was disarmed, stripped, and then released by his captors, with the indication that he was to go. He had moved away from the Indians only a little way when several young braves, armed with lances, started in pursuit. He began his run for the Jefferson River, 5 or 6 miles away.

It is unlikely that many men ever ran better, certainly few have run for higher stakes. After some miles Colter had outdistanced all save one of his pursuers, but his strength was failing, it appeared that his desperate effort had been in vain. He stopped in despair to face the oncoming savage, and as the warrior lunged, Colter seized the lance, which broke in his hands. The Indian, off balance, fell, and Colter killed him with the blade of the weapon.

With only a mile remaining to the stream, he turned to run again, and managed to reach the river ahead of his enemies.

Here the accounts vary, one has it that Colter plunged into the stream and swam under water to a nearby beaver house in which he took refuge. The other, and probably more likely version, says he swam to an island and hid beneath a mass of driftwood that had lodged against the shore.

Although the Indians searched for him for the remainder of the day, probing the tangled mass of drift with poles and lances, Colter, in his place of concealment, avoided detection. After nightfall he made his escape and began his trek of nearly 300 miles back to Lisa's post.

Without weapons or any other means of obtaining food, he managed to reach the fort several days later, in the last stages of exhaustion, feet lacerated and torn by rocks and cactus spines, half starved and barely alive.

Colter made two more trips into the area of the Three Forks. Both times he narrowly escaped death at the hands of the Blackfeet; several of his companions were killed.

In 1810 Colter came to the decision that he had had enough of the Blackfeet, narrow escapes, and the repeated loss of furs, traps, and equipment. He left the country, this time to return to civilization without deviation or delay. He settled on a little farm in Missouri, married, and lived there for his remaining years.

Colter died in 1813, reportedly from jaundice. The legal notice of the final settlement of his estate placed its value at $229.41.

So ended, at an age of only 38 years, the career of one of America's greatest frontiersmen, a forerunner of the famous "Mountain Men." Nevertheless, what a lot of living and adventure Colter crammed into the short span of his 7 years beyond the Missouri.

Colter's part in the early exploration of one of the most rugged sections of America will forever stand as an heroic achievement. He was the West's first great pathfinder, a fitting figure to set the pace for those who followed his lonely paths into the wildest areas of the Far Western frontier.

|

| The Colter Memorial, dedicated in June, 1957, stands on the shore of Colter Bay, Jackson Lake, Grand Teton National Park. Photo by Herb Pownall. |

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Beal, Merrill D.: The Story of Man in Yellowstone, The Caxton Printers, Ltd., Caldwell, Idaho, 1949.

Harris, Burton: John Colter, His Years in the Rockies, Charles Scribner's Sons, New York, 1952.

Mattes, Merrill J.: "Jackson Hole, Crossroads of the Western Fur Trade, 1807-1840," The Pacific Northwest Quarterly, Volume 37, April, 1946 and Volume 39, January, 1948.

Mattes, Merrill, J.: "Behind the Legend of Colter's Hell, the Early Exploration of Yellowstone National Park," Mississippi Valley Historical Review, September, 1949.

Mumey, Nolie: The Teton Mountains, Their History and Tradition, The Artcraft Press, Denver, 1947.

Vinton, Stallo: John Colter, Discoverer of Yellowstone Park, Edward Eberstadt, New York, 1926.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

grte/campfire_tales/chap1.htm

Last Updated: 27-Mar-2004