|

GRAND TETON

Campfire Tales of Jackson Hole |

|

THE MOUNTAIN MEN IN JACKSON HOLE

By MERLIN K. POTTS, Chief Park Naturalist

MOUNTAIN MAN. The very term has an aura of romance, and the mountain man of the Fur Trade Era was a romantic character, as he most frequently appears in the novels of the wild Far West. He also appears as an uncouth, illiterate, morally degenerate, lazy lout, addicted to prolonged debauchery, often little better, sometimes inferior, to the savages with whom he frequently associated. Between this extreme, and the fearless, hardy, resourceful wanderer of the lonely plains and mountain highlands, lies the true measure of these men of the mountains. Some were as bad as they were painted, many were as fine as history describes them. They were the products of their time, neither better, nor worse, than any cross-section of the men of any time.

They were, none-the-less, unique even among the pioneers of their day. Their chosen land was far beyond the outposts of the settlements, their fellows were few, they moved through the most remote sections of America, often alone, sometimes in the company of a handful of companions.

Mountain men were the first to explore the Far West; beyond the Missouri, through the Rockies, across the Great American Desert, from the Southwest to Canada, and to the Western Sea. They came not as explorers, such intent probably never occurred to them. Their sole interest was in the quest for pelts, particularly the fine fur of the beaver. Beaver hats were the vogue during the period of the Western Fur Trade, roughly 1800-40. Until this headpiece was supplanted by the silk hat, the trappers followed the fur, their trails crossing and recrossing virtually every area where beaver were to be taken. Some were independent trappers, some were attached to various fur companies. To the organizers of the trade, the "business men" behind the enterprises, fell the financial rewards. The trappers, except in rare instances, barely made a living at their profession. Their rewards were, many times, an unmarked grave or broken health, a maimed and crippled body, or, if they survived to a ripe old age of perhaps 60 years, memories of a lifetime of adventure multiplied many times beyond the normal conception.

They were indeed a breed of men apart. It is in no way remarkable that their story is one of the most fascinating in our history. Bridger, Smith, Fitzpatrick, Carson, Meek, Sublette, Jackson; these are among the famous names engraved upon the face of the land, markers to the indomitable men who left behind these reminders of the days when the beaver was king of the furbearers.

"Jackson's Hole," the great, mountain-encircled valley lying at the east base of the Teton Range, was, as that excellent historian Mattes puts it so aptly, the "Crossroads of the Western Fur Trade." Trapper trails led into and out of the valley from all directions, through the passes to the east, Two Ocean, Togwotee, and Union, along the Hoback River to the south, through Teton and Conant Passes at either end of the great range to the west, and along the valley of the Snake and Lewis Rivers northward into the Yellowstone Country. From John Colter's memorable trek in 1807-08 through 1840 there was much activity throughout the region. With the decline of the fur trade the valley became once again, and for many years thereafter, a place of solitude, unvisited, as far as history records, by white men.

The name Jim Bridger is synonymous with mountain man. Few frontiersmen from the time of Daniel Boone have so captured the imagination, or been so voluminously treated in western lore. Bridger has been celebrated as the greatest of them all, his true exploits tremendous, his fancied feats fantastic. There were others who shared his fame, he was overshadowed by none, perhaps equaled by a very few.

Bridger was born in Richmond, Virginia, on March 17, 1804, his birthday antedating by less than 2 months the departure of Lewis and Clark on the first great western exploration. The family emigrated a few years later to St. Louis, and Jim and his younger sister were left in the care of an aunt when their mother and father died in 1816 and 1817. By the time he was 14 young Jim was supporting himself and his sister by operating a flatboat ferry, then he became an apprentice in the blacksmith's trade. This mundane life was not for him. There were too many exotic influences in the St. Louis of that time which had a tremendous attraction for a teen-aged youngster. Indians on their ponies jogged along the streets; Mexican muleteers and colorful Spaniards off the Santa Fe Trail strolled through the town; there were boatmen, fur traders, and plainsmen with their tales of buffalo, Indian fights, Lisa, Colter, Lewis and Clark; what boy could resist the lure of adventure which beckoned so importunately just beyond the skyline. Jim could not, he did not. Little sister was growing up, expenses were mounting, and there was a fortune to be made beyond the western horizon.

In March 1822, just after Jim had passed his eighteenth birthday, the St. Louis Missouri Republican carried the following notice:

To Enterprising Young Men. The subscriber wishes to engage one hundred young men to ascend the Missouri River to its source, there to be employed for one, two or three years. For particulars inquire of Major Andrew Henry, near the lead mines in the county of Washington, who will ascend with, and command, the party; or of the subscriber near St. Louis.

(Signed) William H. Ashley

No mention was made as to the employment for one, two or three years, nor was it necessary. What else but the quest for fur! Young Jim signed on, and a month later he was on his way to the promised land, one of the "enterprising young men" of Henry's company, bound up the river by keelboat to become a trapper. He was in distinguished company among experienced frontiersmen, though many of the crew were raw recruits, as green as Jim himself. There were Sublette and Fitzpatrick, Davy Jackson and old Hugh Glass, the latter to figure prominently in Jim's introduction to the frontier.

The outfit lost their horses, which had been traveling overland with a party under General Ashley's command, to the Assiniboines, however, and as Ashley returned to St. Louis, the balance of the command "forted up" at the mouth of the Yellowstone that fall. This was "Fort Union." Thus Jim became a "Hivernant." He wintered in the mountains and was a greenhorn no longer, when spring came he was a Mountain Man.

With the breakup of the ice that spring, Major Henry promptly started on the spring hunt, intending to combine trapping with trading with the Indians. The party was jumped by Blackfeet at or near the Great Falls of the Missouri, and the Indians drove them into retreat. They made their way back to the fort, losing four men killed, and with several wounded. Bridger had his first taste of Injun fightin'. It was not a palatable one.

In the meantime Ashley had not arrived at the fort, but some time after the return of Henry's party Jedediah Smith (also recruited by Ashley in the spring of 1822) arrived with one companion and the most unwelcome news that the General's party had run into difficulty with the Arikaras, and was in dire need of reinforcements. Henry, with about 80 of his men, including Bridger, returned with Smith to aid Ashley, arriving in time to achieve a doubtful and shortlived truce with the Indians, with the help of Colonel Leavenworth and a force of soldiers, trappers, and friendly Sioux, who had moved up from Fort Atkinson.

Major Henry and his men, having received their supplies from Ashley, set out at once for the fort on the Yellowstone, intending to again proceed from there into the wilderness in search of furs. Shortly after the Arikara fight occurred an incident that was to have a pronounced and lasting influence on young Jim. The aforementioned Hugh Glass was a hunter for the party, an elderly, tough Pennsylvanian. On the occasion which led to his claim to fame as a victim of one of the most tragic "bear stories" ever related, he was ahead of the party on a hunt, when he was attacked and mauled by a she-grizzly. So severely was the old man mangled that his companions despaired of his life. Here was a knotty problem. He could not be moved, he could not be left alone. Yet the party wanted to get out of the hostile Indian country and go about the business of collecting furs as speedily as possible. Major Henry decided that two men must remain with old Hugh until he died. No one wanted to stay, but the Major proposed that every man contribute a dollar as an inducement to those left behind with the old man. The men were more than willing to subscribe to the arrangement, Jim volunteered to stay, and another, Fitzgerald by name, reluctantly consented to remain also. So it was determined, and the Major and the rest of the party moved on.

Old Hugh clung tenaciously to life, while Jim and Fitzgerald sat and fretted, constantly in fear of discovery and attack by the hostile Arikaras. Fitzgerald found Indian sign on the third day. As far as he was concerned that clinched it, they couldn't do the old man any good, he was certain to "go under" anyway, in the meantime they were in terrible danger. He finally persuaded Jim to leave the dying oldster, taking with them Glass' rifle, powder, knife, all his "fixins," because it wouldn't be reasonable to show up without them, they wouldn't leave the things with a dead man, and their story to the Major would have to be that Glass had died. The old fellow was barely conscious, and they slipped away, catching up to the rest of the party just before it reached the fort on the Yellowstone.

Jim was worried, memories of the old man haunted him, suppose he hadn't died! Imagine his dismay when a few weeks later Glass appeared in the trappers' camp. Jim expected death at the hands of the hunter, he probably felt that he deserved it, but Glass seemed to be most interested in the whereabouts of Fitzgerald, placing the blame on him.

Glass had an incredible story to tell. Realizing that he had been deserted, he determined to save himself, and crawling, hobbling, barely able to move at all, he started for Fort Kiowa, nearly 100 miles away. He made it, and as soon as possible thereafter he started upriver again to locate Henry's party. He wanted "Fitz." When he learned that Fitzgerald had left the Major and gone downriver to Fort Atkinson, Glass went after him, with the avowed intention of revenge. He found him, but found also that he had joined the Army. The commanding officer at Fort Atkinson heard his story, persuaded him that shooting a soldier would be a serious matter, compelled Fitzgerald to make good the old man's losses, and thus the matter was ended, perhaps not to the complete satisfaction of the justly irate old hunter, but at least without bloodshed. Jim never forgot. The rest of his life the lesson remained with him, and his record of service to others, devotion to duty rather than self-interest, is sufficient evidence that the lesson was well learned.

Bridger's exploits in the years that followed were legion. In 1824 he explored the Bear River, discovering the Great Salt Lake which at that time he believed to be an arm of the Pacific. He advanced from a trapper in the employ of others to a partnership in the Rocky Mountain Fur Company with Fitzpatrick, Milton Sublette, Fraeb and Gervais, when in 1830 they brought out the company of Jedediah Smith, David Jackson, and Bill Sublette. He is best known for his services as a guide. As his knowledge of the Rockies increased with his years of wandering over the west, he repeatedly served as a scout for the Army, in which capacity he was invaluable, his knowledge of Indians and their ways was second to none. He guided many notable expeditions, one of them the Raynolds party, into Jackson Hole. It was said of him that he could brush clear a patch of earth and inscribe thereon, with a twig, an accurate and detailed map of any section of the Northern Rockies, depending only upon a photographic memory of the terrain.

Bridger visited Jackson Hole for the first time in 1825, with Thomas Fitzpatrick and 30 trappers, following Jedediah Smith's route of the previous year, that is by way of the Hoback River from the south. They passed through the Hole, going north along the Snake River into the Yellowstone. This was probably the first trapping venture with Jackson Hole as the center of operations. Mattes says, in Jackson Hole, Crossroads of the Fur Trade, 1807-1840:

This was a notable occasion, for the full glory of the Tetons was then revealed for the first time to these two young fur trappers who were destined in later years to become famous as guides for the government explorers and the emigrant trains, and as scouts for the Indian-fighting armies.

Bridger's trails, and those of many others, crossed and recrossed the valley at the foot of the Tetons many times in the ensuing several years, as they moved to and from the rendezvous sites on Bear River, the Green, Pierre's Hole, and the Wind. Through this period the Hole justified its designation as the "crossroads." Traffic was heavy, and upon at least one occasion, following the Pierre's Hole rendezvous of 1832, two men (not with Bridger) were killed by the Blackfeet near the mouth of the Hoback. These men did not, for a time, attain even the "unmarked grave" reward. Their bones were discovered and buried the following August by men of the American Fur Company.

Bridger's fame as a Rocky Mountain guide was well established by 1859, when he was employed by Captain W. F. Raynolds, of the Corps of Engineers of the U. S. Army, to assist his expedition in the exploration of the Yellowstone and all its tributaries. The Raynolds expedition left St. Louis on May 28, 1859, and included about 15 scientific men, one of whom was the later renowned Ferdinand V. Hayden. The expedition wintered on the Platte near the present site of Glenrock, Wyoming.

During the several months that Raynolds and his men were idling away the winter, Bridger's stories of the Yellowstone aroused in Raynolds an intense desire to see these wonders for himself, and he determined to do so. The old guide and his leader were both to suffer keen disappointment. The party left the winter camp on May 6, 1860, and headed for the Wind River country, eventually reaching Union Pass, so named by Captain Raynolds because he thought it was near the geographic center of the Continent, on May 31. Bridger and the Captain reconnoitered to the north, but found the route discovered by Bridger in previous years, Two Ocean Pass, blocked by snow too deep to negotiate. They were thus forced, to their profound regret, to continue on down the Gros Ventre, entering Jackson Hole on June 11. So Raynolds was unable to verify Bridger's tales of the wonders of the Yellowstone, marvels that Jim was as anxious for him to see as the Captain was to see them.

The Snake River was a raging torrent, but a boat was contrived of blankets and a lodge-skin of Bridger's stretched over a framework of poles. The animals were persuaded to swim the river, and the party eventually managed the crossing. One man was drowned, however, while trying to find a ford. Raynolds and his men left Jackson Hole by way of Teton Pass and proceeded north through Pierre's Hole.

Although Bridger was engaged as a guide for many subsequent explorations, including a survey of a more direct stage and freight route between Denver and Salt Lake City, he did not come again to Jackson Hole. He made his last scout for the Army in 1868.

Bridger's name appears on landmarks and features throughout the Rockies. In Wyoming there is Bridger's Pass across the Continental Divide a short distance southwest of Rawlins; Fort Bridger, a small town on U.S. Highway 30 near the site of the Fort established by Bridger in 1843; the Bridger National Forest, and Bridger Lake near the southeastern corner of Yellowstone National Park, to name only a few.

Bridger's "home" was in the mountains he loved. He bought property near Kansas City, a small farm and a home in Westport, where various members of his family lived, but Jim spent little time there until his declining years. He had a large family, was survived by four children from his Indian wives. Jim didn't believe in the practice of plural marriage, as many of the mountain men did. He was married three times, successively to women of the Flathead, Ute, and Snake tribes, his third wife died in 1858. He was a good family man. His children were sent to school in the east, except for one daughter, Mary Ann, who was placed in the Whitman Mission School at Waiilatpu, Oregon, and who died tragically in the Whitman Massacre of 1847.

Jim Bridger's yarns of the west have long been famous. He could supply facts, when facts were needed, but he loved to embroider his facts into fanciful tales for the edification and delight of the "greenhorns," to some extent because his facts were sometimes doubted. One of his greatest stories concerned the petrified forest of the Yellowstone. According to Jim not only the trees were "peetrified," but there were "peetrified birds asettin' on the peetrified limbs asingin' peetrified songs." One time he was riding through this section when he came to a sheer precipice. He was upon it so suddenly that he was unable to check his horse, which walked off the cliff into space and proceeded on its way because even gravity had "peetrified."

Jim died on July 17, 1881. His last years were not pleasant. He had a goitre from which he suffered, rheumatic miseries plagued him, and his sight failed. By 1875 he was totally blind. As his old eyes grew dim he longed for his mountains, he said a man could see so much farther in that country.

His old friend, General Grenville M. Dodge, had erected above his grave in Mount Washington Cemetery in Kansas City a memorial monument which bears the inscription:

1804-James Bridger-1881. Celebrated as a hunter, trapper, fur trader and guide. Discovered Great Salt Lake 1824, the South Pass 1827. Visited Yellowstone Lake and Geysers 1830. Founded Fort Bridger 1843. Opened Overland Route by Bridger's Pass to Great Salt Lake. Was a guide for U. S. exploring expeditions, Albert Sidney Johnston's army in 1857, and G. M. Dodge in U.P. surveys and Indian campaigns 1865-66.

Jedediah Strong Smith, a contemporary of Bridger's, was another of General Ashley's "enterprising young men" who came west with the General and Major Henry in 1822. He was one of the rawest of the green hands, yet was one of the first to attain stature. He was older than Bridger by 5 years, head of an Ashley party at the end of one year on the frontier, in 2 years a partner with the General, and in 3 the senior partner of the fur-trading company of Smith, Sublette, and Jackson.

To say that Smith was second only to Bridger in his prominence as a mountain man, to attempt to place any of the leaders among the trappers in any order of rank or importance, would be like trying to rate the military commanders of history. Each in his own rugged individualistic way moved toward his own destiny. Many would have risen to even greater fame than they achieved, had they not met with misfortune early in their careers. So, we may assume, it might have been with Smith. He was already a famous figure in the West at the time of his untimely death in 1831.

He was an unusual type of man to be a frontiersman, most would have said it was unlikely that he would last long or rise to any prominence in the rough, brawling, blood-and-thunder ways of the west of that day. He did not smoke or chew tobacco, was never profane, and rarely drank any spirituous liquor. He was a profoundly religious man, always carried his Bible with him, and allowed nothing to shake or alter his religious beliefs. For his day he was also a well-educated man, and one of the few who kept a journal, in which he recorded in some detail his experiences.

For all this divergence from the usual ways of his fellows, he was respected and admired, accepted by the other trappers, affectionately known as "Old Jed" or "Diah," and even upon occasion referred to as Mr. Smith. He was the first of the trapping fraternity to reach California overland from the Rockies, the first across the Sierras, and the first to reach Oregon by way of the West Coast.

When Henry had established his fort at the confluence of the Yellowstone and the Missouri in 1822, Smith was sent back to St. Louis to advise General Ashley of the needs of Henry and his men for the following year. Smith then accompanied Ashley west in the spring of 1823, and as mentioned previously, was sent ahead to enlist Henry's aid when Ashley ran into trouble with the Arikaras. He again returned with the General to St. Louis, and in February 1824, Ashley sent him out again with a party which traveled overland by pack train. On this occasion Smith and his party made the first crossing, east to west, of the famous South Pass at the head of the Sweetwater River, the pass which was to become the crossing of the Great Divide on the Oregon Trail. This pass had been used by the Astorians, traveling in the opposite direction, in 1812. (General Dodge's memorial, crediting discovery of the pass to Bridger in 1827, was thus in error, although various routes were being "discovered" and "re-discovered" at intervals by individuals who had no knowledge that others had preceded them.) A new era in fur trade history was opened when Smith's party found the rich beaver fields at the head of Green River. As Smith and his contingent moved north from the Green, they entered Jackson Hole by way of the Hoback, passed through the valley, and crossed north of the Tetons by way of Conant Pass into Pierre's Hole (the Teton Basin.) Thus Smith preceded Bridger into Jackson Hole by a year.

Although Smith became possibly the greatest of the trapper-explorers, at least with relation to the wide territory covered in the course of his journeys, he did not return to Jackson Hole. He was killed by Comanches only 7 years later on the Santa Fe Trail. Crossing desert country with a wagon train, Smith was scouting ahead for water when he was slain. His remains were never found, the story of his death came to light when Mexican traders, who dealt with the Comanches, brought his pistols and rifle to Santa Fe.

William "Bill" Sublette and David E. Jackson became Smith's partners in the fur trade when they bought Ashley's interests in the business at the rendezvous near the Great Salt Lake in 1826. Both of these men had been among those who made up Ashley's 1822 expedition, Sublette at that time was 24 years of age, a Kentuckian whose family moved to Missouri in 1817. Jackson has remained throughout the years an enigma, practically nothing is known of him before his advent into the fur trade, or following his activity as a mountain man.

Sublette was the entrepreneur of the trio. It was Bill who handled the outfitting, the business contracts, the transportation of trade goods and furs. That the partnership was successful is indicated by their disposal of their interests to Bridger and his partners in 1830 for an overall sum involving some $16,000. Sublette and his partners were shrewd enough to anticipate the gradual dissolution of the fur trade, which influenced their desire to get out of the business. It was Sublette's wagon caravan from St. Louis to the Popo Agie and return in 1830 that proved the overland trail could be used by wheeled vehicles, this was the caravan that pioneered the immigrants' route to Oregon. Sublette later returned to the west as a trader, in partnership with Robert Campbell, and built Fort William (later Fort Laramie) in 1834.

Sublette and Jackson first entered Jackson Hole in 1826, after the rendezvous of that year near the Great Salt Lake. They crossed the lower end of the valley on their way to Green River, while their new partner, Smith, was headed with another contingent of trappers southwest across the desert toward California.

The system of trading at annual summer "rendezvous," several of which have been previously mentioned, was inaugurated by Ashley in 1825. The rendezvous site of that year was on Henry's Fork of the Green River. By such a method, more flexible than the previously used "fixed fort" system, the trappers assembled at a previously determined place, conveniently located for the widely separated trapper bands. The trader brought his goods to the site where furs were exchanged for the trade goods. It was a time of celebration, frolic, and general carousal for all concerned. The rendezvous site can be likened to the hub of a wheel, the trails followed by the trappers as they came in from the spring hunt and departed for the fall hunt were the spokes. Thus rendezvous sites were on the Green, Wind, Popo Agie Rivers, at the Bear and Great Salt Lakes, in Pierre's Hole, and finally at Fort Bonneville. Jackson Hole was never a rendezvous site because of the difficulty of access for the traders over the high mountain passes surrounding the valley.

|

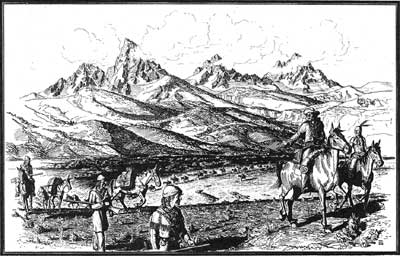

| A fur brigade in Pierre's Hole (Teton Basin, Idaho), at the western base of the Teton Range. |

There is no positive evidence of trapping activity in the valley in 1827-28, although it is quite probable that the Hole received its share of attention. In 1829, however, Sublette and Jackson joined forces again in Jackson Hole, where by previous arrangement they were to meet "Diah." Smith did not appear, and the partners were greatly concerned by his absence. Tradition has it that Sublette named "Jackson's Hole" and "Jackson's Lake" in honor of his associate while they were encamped on the shore of the lake waiting for Smith. Smith was eventually located in Pierre's Hole by one of the Sublette-Jackson party, Joe Meek, and the partners were finally reunited there, Jackson and Sublette moving over via Teton Pass.

Throughout the period 1811-40, nearly every mountain man prominently connected with the fur trade visited Jackson Hole. It was an area greatly favored by Jackson, which undoubtedly accounts for Sublette's most appropriate name. Following Colter's discovery of the valley, it was traversed in 1811 by three employees of the St. Louis-Missouri Fur Company, John Hoback, Edward Robinson, and Jacob Reznor. These three, en route to St. Louis in the spring, encountered the Astorian expedition (John Jacob Astor's overland party of the American Fur Company) and agreed to guide the party, commanded by Wilson Price Hunt, over a part of the westward route. This group entered Jackson Hole that fall by way of the Hoback River, then went west over Teton Pass. Robert Stuart brought a returning band of Astorians back in the fall of 1812, following the same general way and discovering the "South Pass," as they moved eastward beyond the Green.

British interests took the initiative in the exploration of the fur country following the War of 1812 and a general, and temporary, decline of American interest. In 1819 Donald McKenzie of the Northwest Company brought a large party through Jackson Hole and on north into the Yellowstone.

The Americans again entered the picture with Smith's previously mentioned venture of 1824, and from that time forward the list of Jackson Hole visitors reads like a "Who's Who" of the western fur trade. There were James Beckwourth (with Sublette), all of Bridger's partners (Fitzpatrick, Milton Sublette, Fraeb, and Gervais), Nathaniel Wyeth, Captain Benjamin L. E. Bonneville, and probably on one occasion the redoubtable Kit Carson.

The era of the mountain man was brief. It is doubtful that the trappers, traders, and fur company men realized the significance of their exploits in the expansion westward of a new nation. Yet without their activities the exploration of the western lands might have been long delayed, and the claim of the United States to the Pacific Northwest much less secure.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alter, J. Cecil: James Bridger, Trapper, Frontiersman, Scout and Guide, Shepard Book Company, Salt Lake City 1925.

Chittenden, Hiram Martin: A History of the American Fur Trade of the Far West, Academic Reprints, Stanford, California 1954.

Mattes, Merrill J.: "Jackson Hole, Crossroads of the Western Fur Trade, 1807-1840, The Pacific Northwest Quarterly, Volume 37, April, 1946 and Volume 39, January, 1948.

Morgan, Dale: Jedediah Smith and the Opening of the West, The Bobbs-Merrill Company, Incorporated, New York 1953.

Sullivan, Maurice S.: Jedediah Smith, Trader and Trailbreaker, Press of the Pioneers, Incorporated, New York 1936.

Sunder, John E.: Bill Sublette, Mountain Man, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Oklahoma 1959.

Vestal, Stanley: Jim Bridger, Mountain Man, William Morrow and Company, New York 1946.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

grte/campfire_tales/chap2.htm

Last Updated: 27-Mar-2004