|

Theodore Roosevelt and the Dakota Badlands |

|

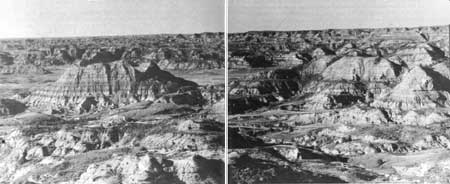

"Hell with the fires Out," where Sully first saw

the Badlands. Painted Canyon, South Unit.

Early History of the Badlands

Surprisingly little is known about the occupation or use by Indians of the Little Missouri Badlands prior to travel by white men and their settlement in the region. During the 19th century, Crow, Cheyenne, Sioux, Anikara, Mandan, and Gros Ventre Indians variously occupied sites along the Missouri River above Bismarck, from the mouth of the Knife River to the mouth of the Yellowstone. The area drained by the Little Missouri, the largest tributary of the Missouri in this region, was frequented by these tribes for hunting and camping.

FUR TRADERS AND TRAVELERS. It was probably not until about 1804 that white men first viewed the Little Missouri Badlands. That year Jean Baptiste LePage, a Canadian "voyageur," descended the Little Missouri River and joined the Lewis and Clark Expedition at its winter camp at Font Mandan north of Bismarck. During the next two decades many trapping and exploring expeditions, notably those of John Colter, Manuel Lisa, Joshua Pilcher, Alexander Henry, William Sublette, William Kipp, and Brig. Gen. Henry Atkinson passed the mouth of the Little Missouri River en route to the Yellowstone River or the Three Forks region. Doubtless the upper reaches of the Little Missouri were explored by trappers or hunters attached to these expeditions, but no definite record of their wanderings survives.

Kipp's trading post, at the mouth of White Earth River, below present Williston, built in 1826, was the white habitation nearest to the Badlands. With the inauguration of steamboat travel on the Missouri in 1832 to Fort Union—an American Fur Company trading post near the present Montana-North Dakota boundary—a succession of fur traders, adventurers, artists, and scientists passed the mouth of the Little Missouri. Among the more distinguished travelers were Prince Maximilian of Wied, Carl Bodmer, Father Pierre de Smet, George Catlin, Kenneth McKenzie, John James Audubon, and Pierre Chouteau.

In 1845, the American Fur Company erected Fort Berthold at Like-a-Fishhook Village, stronghold of the Arikara, Gros Ventre, and Mandan Indians, about 15 miles below the mouth of the Little Missouri. These settlements, coupled with a growing traffic along the Missouri River, would make it seem probable that the Little Missouri wilderness was penetrated frequently by hunting or exploring parties.

THE INDIAN WARS. The Little Missouri River region was first brought to the attention of the American people through the campaign of Brig. Gen. Alfred Sully against the Sioux in 1864 in retaliation for their bloody uprising against the Minnesota settlements. In July 1864, Sully's force established Fort Rice on the Missouri River south of Bismarck. It then marched west accompanied by a long wagon train of men, women, and children bound for the gold fields of Montana and Idaho. Sully learned that the Sioux were encamped above the mouth of the Little Missouri at a favorite hunting ground in the Killdeer Mountains. His troops attacked the Indians there, dispersing them and destroying their camp and supplies.

The expedition resumed its westward march to the edge of the Badlands, and very likely camped in what is now the southeast corner of the park. Here, according to legend, Sully stated that the Badlands looked like "hell with the fires out." In his official report Sully described the country as "grand, dismal and majestic." From the time it arrived at the Little Missouri River until it left the Badlands, Sully's force was subjected to intermittent Sioux attacks. The expedition eventually reached the Yellowstone River, and descended it and the Missouri to Fort Berthold before returning to Fort Rice.

THE COMING OF THE RAILROAD. While Sully was campaigning across the Dakota plains, railroad interests were formulating a plan to link the Great Lakes and Puget Sound. In July 1864, Congress passed the Northern Pacific Railroad Act. Already the miner with his pan and gun had caused uneasiness among the Indians. It was not long before the Sioux attacked the railroad surveyor with his compass and chain. After witnessing the decimation of the buffalo, which accompanied the construction and completion of the railroads farther south, the Indians were determined to prevent the advance of the Northern Pacific rail line west of the Missouri River. This made it necessary for the military to escort each railroad survey party.

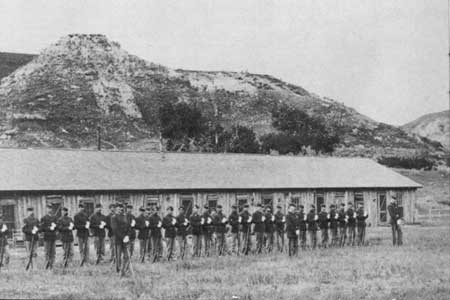

"Custer's Wash"—route used by most military

expeditions through the Badlands.

In 1871, Maj. Joseph N. Whistler furnished an escort for a survey party which followed General Sully's route through the Badlands to the Yellowstone River. The following year, in an attempt to avoid the Badlands, Col. David S. Stanley's troops escorted a survey party south of the "oxbow" of the Little Missouri River and about 25 miles south of Whistler's survey. They continued almost straight west to the mouth of Powder River (near Terry, Mont.). There they awaited the arrival of Col. Eugene M. Baker who was to escort another party of railroad surveyors east from Bozeman, Mont., to the Powder River. Sioux Indian attacks, however, led by Chief Sitting Bull and Chief Gall, forced Baker's command to abandon the survey west of Pompey's Pillar, Mont. The 1872 survey disclosed that the southerly route was not as satisfactory as Whistler's 1871 route near what is now the south boundary of the park.

Lt. Col. George A. Custer and the Seventh Cavalry accompanied Stanley's 1873 survey from Fort Abraham Lincoln near Bismarck. There were no Indian attacks until the expedition was north of present Miles City, Mont. There a major engagement between Sitting Bull's Sioux and Custer's Seventh Cavalry took place. After the survey had been completed, however, financial problems and further Indian hostility delayed construction of the railroad west from Bismarck.

During part of the autumn and winter of 1875—76, Sitting Bull's band of about 500 lodges camped in the Badlands, apparently at the junction of Beaver Creek and the Little Missouri River. (This site is about 10 miles north of and downstream from Roosevelt's Elkhorn Ranch.)

When Custer passed through the Badlands in 1876 en route to the Battle of the Little Bighorn, his regiment camped about 5 miles south of where the town of Medora was soon to be built, on the site of the present Custer Trail Ranch. While there, Custer led a scouting party 50 miles along the Little Missouri in search of Sitting Bull's camp, but found no Indians. A blizzard on June 1 and 2 forced the regiment to camp in the badlands north of Flat Top Butte about 8 miles west of the present Custer Trail Ranch. From this camp the expedition marched up the Yellowstone River Valley to the mouth of Rosebud Creek. After a conference there with Brig. Gen. Alfred H. Terry and Col. John Gibbon, Custer led the Seventh Cavalry northward to its fatal encounter with the Sioux.

Later in 1876, Brig. Gen. George Crook's force pursued some of the Sioux that had participated in the Custer fight. These Indians moved from the Little Bighorn to the Little Missouri and then east along what is now the south boundary of the park. When they came to the plains region east of the Badlands, they turned south. Continuing the pursuit, Crook caught up with the Indians north of the Black Hills; there he fought and beat them in the battle known as Slim Buttes.

Northern Pacific Railroad construction west of

Bismarck in 1879. Courtesy Haynes studios Inc.

Except for sporadic attacks, Sioux resistance had been broken by 1879, and the Northern Pacific Railroad began laying rails west from Bismarck. Late in 1879 the railroad track-laying headquarters was located on the west bank of the Little Missouri River.

In November 1879, to protect the railroad construction workers, a company of the Sixth Infantry, commanded by Capt. Stephen Baker, constructed there a military post which became known as the Badlands Cantonment. The cantonment was located about three-quarters of a mile northwest of, and across the Little Missouri River from, the present village of Medora. The sutler's store at the cantonment served as a clubhouse for the post and the surrounding region. Frank Moore served as sutler or post trader. The Badlands Cantonment was a one-company post, and only about 50 men were stationed there.

Badlands Cantonment, 1880. Courtesy Haynes

Studios Inc.

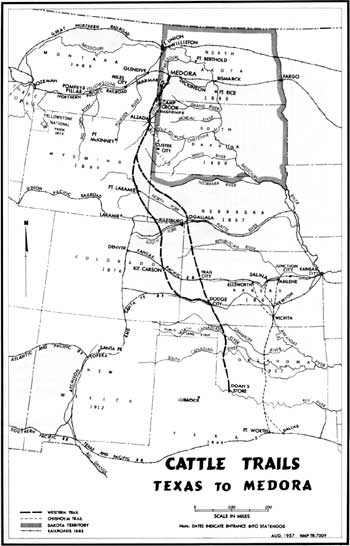

Cattle Trails: Texas to Medora. (click on

image for an enlargement in a new window)

THE OPEN RANGE CATTLE INDUSTRY. As a result of the Indian wars in the 1870's, the power of the Plains Indians was broken and the tribes placed on greatly reduced reservations. This, and the advent of the railroad on the central plains, had a direct effect on the cattle industry in Texas. There, the knowledge that the northern plains were now open to cattle raising without fear of Indian depredations, and that there were railheads connecting with the cattle markets in the East, led to the growth and expansion northward of the open range cattle industry.

This industry had its origin on the Texas plains before the Civil War. During that war the cattle had multiplied by the thousands. Soldiers, returning from the war, found the ranges covered with stock for which there was no market, and therefore selling for about a dollar a head. But the succulent grasses of the plains, and the northern railheads of the Dakota Territory opened a vista of rich profits, and the great cattle drives to the north were organized. Thousands of longhorns were driven over the Chisholm, Western, and other well-known trails. Famous cowtowns along the way, such as Newton, Wichita, Abilene, Ellsworth, and Ogallala, became shipping points to the eastern markets for Texas cattle.

The open range cattle industry was given another boost when miners and settlers poured into the Dakota Territory after the discovery of gold in paying quantities in the Black Hills. At about this same time, the industry was also helped by the hidehunters who were killing off the buffalo herds on the northern plains, leaving the grasslands for more cattle.

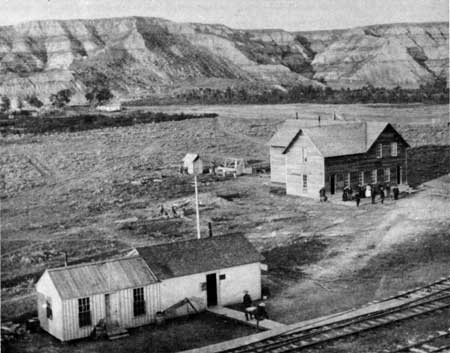

Pyramid Park Hotel and Depot, 1881.

Courtesy Haynes Studios Inc.

|

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Jan 17 2004 10:00:00 am PDT |