|

Theodore Roosevelt and the Dakota Badlands |

|

De Mores packing plant. Courtesy State

Historical Society, North Dakota.

Roosevelt the Rancher

Soon after Roosevelt returned to his Maltese Cross Ranch in 1884 he began planning to extend his ranching operations. He wrote his sister, Mrs. Anna Cowles:

. . . For every day I have been here I have had my hands full. First and foremost, the cattle have done well, and I regard the outlook for making the business a success as being very hopeful. This winter I lost about 25 head from wolves, cold, etc., the others are in admirable shape, and I have about a hundred and fifty-five calves. I shall put on a thousand more cattle and shall make it my regular business. In the autumn I shall bring out Sewell and Dow and put them on a ranch with very few cattle to start with, and in the course of a couple of years give them quite a little herd also.

Acting on this decision, Roosevelt sent his ranch foremen, Sylvane Ferris and William Merrifield, to Iowa to purchase 1,000 cattle. In mid-June the Cow Boy noted Roosevelt's expanding operations:

Mr. Roosevelt is still at Ferris & Merrifield's ranch, hunting and playing cowboy. It seems to be more congenial work than reforming New York state politics. He is thoroughly impressed with the profit of raising cattle in the Bad Lands, as his vigorous backing of Ferris Bros. & Merrifield testifies.

Elkhorn Ranch veranda.

In the summer of 1884 Roosevelt took steps to establish another ranch. He selected the site for this second ranch, which he called Elkhorn, on the Little Missouri River about 35 miles north of Medora. (In common with most of the ranches of that period, both the Elkhorn and Maltese Cross were on railroad or Government land, so Roosevelt did not obtain title to either of them.) He induced two former Maine guides, Wilmot Dow and William Sewall, to become foremen of the new ranch. By August, his cattle numbered about 1,600 head. The Elkhorn buildings, begun in the autumn and winter of 1884-85, were completed in the early summer of 1885. The Elkhorn Ranch house was one of the finest in the Badlands. Roosevelt described it as the "Home Ranch House." Henceforth he spent most of his time in the Badlands there instead of at Maltese Cross.

After returning to the Badlands in the spring of 1885, Roosevelt took part in the roundup for Little Missouri District 6. Such roundup districts, as a rule, conformed to the drainage basin. These roundups were necessary because of the nature of the open range cattle industry.

Very few ranchers owned more than a section on two of land and many, including Roosevelt, were squatters owning no land whatsoever. Each rancher claimed a certain area as his range according to the number of cattle he possessed and his priority of use. The ranges were not fenced, and cattle from different ranches intermingled. Two general roundups were held each year to gather together the cattle from the range and separate them according to ownership. The spring roundup was chiefly concerned with branding calves from that year and any yearlings that had escaped branding the previous year. Cattle were handled more gently during the second, the beef, roundup in the autumn. Marketable cattle were driven to Mingusville (Wibaux), Dickinson, or Medora for shipment, on for slaughter at the De Mores packing plant in Medora.

The roundup started from the mouth of Box Elder Creek on the Little Missouri. The men worked down the river to Big Beaver and up that stream until they made a juncture with men from the Yellowstone roundup. Cattle ranging within 40 miles east of the Little Missouri were driven to that river before the general roundup. It was usually necessary for each ranch to have representatives in adjacent roundup districts in addition to its own. The cook drove his outfit's wagon with bedding, food, and other provisions for the men. About 50 or more men were assigned to a district. Each cowboy had a string of 8 or 10 horses.

On a typical day's roundup one or two men would start from the head of each stream or draw in the district to be covered, driving the cattle ahead of them to a point of concentration which might be a wide bottomland near the river, like Beef Corral Bottom. Cutting the herd (separation of cattle according to brands) usually took place at the point of concentration. Both horse and rider had to be well trained to cut individual cattle from a restless herd of several thousand. Cutting was not a job for greenhorns or dudes.

Elkhorn Ranch stable.

Like the long drive from Texas, the roundup required a well-trained team. In contrast to the long drive it was desirable to end the roundup as soon as possible without being too hard on the horses they rode or the cattle they drove. Only the most experienced men were assigned to the various tasks. Roosevelt never claimed to be a good roper or more than an average rider by ranch standards. Accordingly, while on the roundup he was not assigned the important tasks of cutting, roping, or branding. In the spring roundups, however, he provided fresh meat for the cowboys by hunting.

At the time of the spring roundup of 1885, Roosevelt apparently added more cattle to both of his herds. A contemporary news item stated:

Fifteen hundred head of steers, yearlings and two's came in Thursday morning for the Elkhorn and Chimney Butte ranches of Theodore Roosevelt. They were in fair condition after their long ride and except for the disadvantage of a large number being yearlings, give every evidence of growing into good beef. The larger majority are steers. A good lot of Short-horn bulls and one Polled-Angus were in the herd. A thousand of these cattle will be driven to the Elkhorn ranch and five hundred to the already well-stocked Chimney Butte ranch.

Theodore Roosevelt on the roundup, 1883.

Courtesy Houghton-Mifflin Co.

Cattle losses were light on the northern plains during the winter of 1885-86. Unlike the region farther south, the winter in Dakota and Montana was comparatively mild. After spending that winter in New York City, Roosevelt returned to Dakota in March. Soon after his arrival he wrote Mrs. Cowles: "Things are looking better than I expected; the loss by cattle has been trifling. Unless we have a big accident I shall get through this all right. If not I can get started with no debt."

A letter written about 3 months later to his brother-in-law, Douglas Robinson, expressed similar sentiments:

. . . While I do not see any very great fortune ahead yet if things go on as they are now going and have gone for the past three years I think I will each year net enough money to pay a good interest on the capital, and yet be adding slowly to my herd all the time. I think I have more than my original capital on the ground, and this year I ought to be able to sell between two and three hundred head of steers and drystock.

During 1885-86, Roosevelt's ranching operations were at their peak. Unfortunately, there is no information other than that provided by the tax records of Billings and Stark Counties and the census records to show just how many cattle he owned outright at any time. The estimates vary from about 3,000 to 5,000 head. He was not the biggest operator in the Badlands; neither was he one of the smallest. The census rolls for 1885 disclose that Roosevelt was the fourth largest cattleman in Billings County, which was then of considerably larger area than at present. The census records also show that Ferris, Merrifield, and Roosevelt together owned 3,350 cattle and 1,100 calves. It is highly probable that these figures represent somewhere near the maximum number of cattle on the two Roosevelt ranches. His total investment amounted to about $82,500. Outfits such as the "Three Sevens," "Hashknife," and the "OX" ran as many as 15,000 head of cattle on the Dakota ranges.

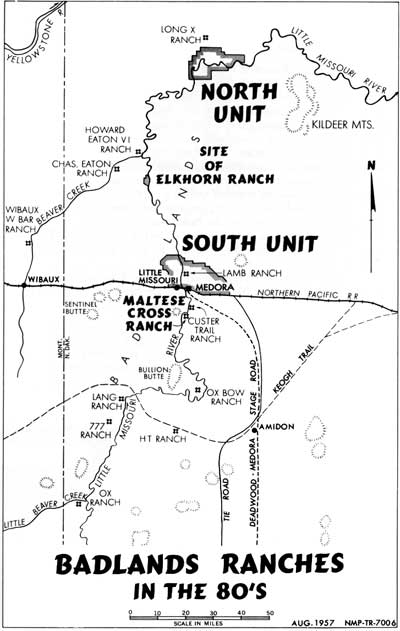

Badlands Ranches in the 1880's.

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

In the Little Missouri spring roundup of 1886, Roosevelt took part as co-captain. Letters to his family indicate he spent considerable time in the saddle. On June 7 he wrote his sister:

. . . I have been on the roundup for a fortnight and really enjoy the work greatly; in fact I am passing a most pleasant summer, though I miss all of you very, very much. We breakfast at three every morning, and work from sixteen to eighteen hours a day, counting night guard; so I get pretty sleepy; but I feel strong as a bear.

Elkhorn Ranch buildings from the Little Missouri

River. Photograph taken by Theodore Roosevelt. Courtesy

Houghton-Mifflin Co.

Roosevelt apparently spent part of his time during the roundup writing and hunting for he wrote several weeks later to his sister: "I write steadily three or four days, and then hunt (I killed two elk and some antelope recently) or ride on the round up for many more."

One morning that spring at the Elkhorn Ranch, Roosevelt discovered that his boat had been stolen. His foremen, Sewall and Dow, immediately improvised another boat and the three started their search for the culprits. The weather was bitterly cold. At the mouth of Cherry Creek (about 12 miles east of the North Park), Roosevelt and his foremen caught up with the three thieves, while they were encamped, got "the drop" on them, and forced the trio to surrender. For several days both captors and prisoners were unable to travel because of ice jams in the river. Roosevelt passed his idle time by reading Tolstoy's Anna Karenina and some of the writings of Matthew Arnold. Provisions ran short. After obtaining supplies and a wagon from the Diamond C Ranch, located several miles north west of the present town of Kildeer, Roosevelt took the prisoners by wagon to Dickinson and turned them over to the sheriff. Meanwhile, his foremen in the recovered boat descended the Little Missouri and Missouri Rivers to Mandan, from which point they shipped the boat by rail to Medora. The 3 thieves were tried in Mandan the following August and 2 were sent to the penitentiary.

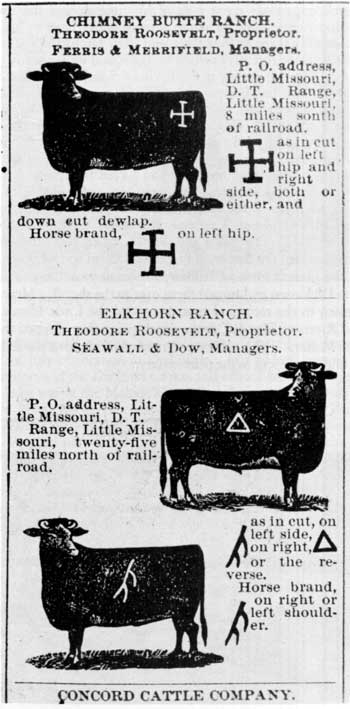

Roosevelt's brands from "Stockgrowers Journal,"

Miles City, Mont. (Sewall's name is misspelled.) Courtesy

Houghton-Mifflin Co.

That summer Roosevelt was one of the featured speakers at the Fourth of July celebration in Dickinson. His address received favorable comment in the Dickinson Press and other Dakota newspapers.

While he was at the Maltese Cross, and during the intervals he was in New York, Roosevelt completed writing his Hunting Trips of a Ranchman as well as several articles for Outlook and Century magazines. A good part of his Life of Thomas Hart Benton was written at the Elkhorn Ranch. Later, he wrote The Winning of the West, undoubtedly drawing on his Badland's experiences for his understanding of pioneer conditions. The bookshelves at the Elkhorn Ranch reflected his naturalist and historical interests. Included among the books to be found there were Elliot Coues' Birds of the Northwest and Col. Richard Dodge's Plains of the Great West. The works of Irving, Hawthorne, Cooper, and Lowell were represented, and there was also lighter reading. Often when hunting or on the roundup, he carried a book in his saddle pack. Such cultural interests and attainments, needless to relate, were quite a rarity on the cattlemen's frontier.

View westward across the Little Missouri River to

the site of Elkhorn Ranch, at left center.

|

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Jan 17 2004 10:00:00 am PDT |