|

Theodore Roosevelt and the Dakota Badlands |

|

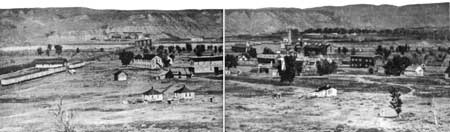

A group of Roosevelt's contemporaries in the

Badlands. Third from left seated is A. C. Huidekoper, famous

rancher. Courtesy Houghton-Mifflin Co.

The Winter of 1886-87

Prior to 1886, nature had been kind to Roosevelt and his neighboring ranchers in the Little Missouri Badlands. Their losses during the previous winters had been relatively small. The winter of 1885-86 also was a mild one on the northern plains and there was but little snow in Dakota and Montana. On the other hand, the winter on the southern plains had been extremely severe. During the summer of 1886 cattlemen from the south continued to drive herds to the parched and already overstocked ranges of the north.

By midsummer the situation had become alarming. When Roosevelt passed through Mandan en route to New York a reporter of the Mandan Pioneer interviewed him:

A few days ago, Mr. Theodore Roosevelt passed through Mandan on his way to New York after spending four months on his ranch in the western part of the territory. . . . Then, speaking of the season on the ranches, he stated where they are wisely and honestly managed they are now paying fairly well but no excessive profits. The days of excessive profits are over. There are too many in the business. In certain sections of the West the losses this year are enormous, owing to the drouth and overstocking. Each steer needs from fifteen to twenty-five acres, but they are crowded on very much thicker, and the cattlemen this season have paid the penalty. Between the drouth, the grasshoppers, and the late frosts, ice forming as late as June 10, there is not a green thing in all the region he has been over. . . .

As summer passed, range conditions continued to become worse. Little rain fell and grazing was poor. Fires destroyed much of the grass that remained. The fate of many stockmen depended upon a mild winter. But as one writer said of the winter of 1886-87, "nature and economics seemed to conspire together for the entire overthrow of the [open range cattle] industry." Late in November the first severe storm struck. The Bismarck Tribune described it as "in many respects the worst on record." Comparatively mild weather followed during the first half of December and a part of the snow melted. Then subzero weather in late December, which lasted until mid-January, formed a crust of impenetrable ice from the melting snow. Cattle could not get through the crusted snow to the grass below. As a result, many of them perished. New heavy snows fell. During the middle of January there was thawing weather accompanied by rain. Again the soggy snow froze. Throughout the remainder of January and during most of February there was continued subzero weather and more heavy snows. Only warm chinook winds which struck in the northern plains in early March saved the stockmen from complete disaster.

Cattle in a blizzard. From "Harper's Weekly," Feb.

27, 1886. Drawing by Charles Graham from a sketch by Henry

Worrall.

The first reports of the results of the winter were quite optimistic. But it was not until after the roundups of the summer that the cattle men were able to appraise their losses.

Roosevelt had returned to New York City in the late summer of 1886, and received the Republican nomination for Mayor of New York City. But in the November election he suffered a severe defeat. The next month he married Miss Edith Carow in England, and the couple spent the winter honeymooning in Europe.

Reports of the hard winter on the northern plains and the heavy losses in cattle brought Roosevelt back from Europe. He went immediately to Medora to study the situation. From there he wrote his friend, Henry Cabot Lodge, soon after his arrival:

Well, we have had a perfect smashup all through the cattle country of the northwest. The losses are crippling. For the first time I have been utterly unable to enjoy a visit to my ranch. I shall be glad to get home.

He wrote his sister in a similar vein:

I am bluer than indigo about the cattle; it is even worse than I feared; I wish I was sure I would lose no more than half the money ($80,000) I invested out here. I am planning to get out of it.

Roosevelt attended the spring meetings of the stockmen's association. There it was decided that, owing to the heavy losses, the Little Missouri stockmen should not hold a general roundup. Believing that the cattle had drifted with the storm, the group decided to send a party to the Standing Rock Indian Reservation in search of them.

The ranchers combed the country in vain for the cattle they believed had drifted in the winter storms. As one stockman pointed out, "Search it [the range] minutely and there was no sign of the tragedy. The carcasses withered up by the end of August, a few bones grass-covered at wide intervals and that was all. How the thousands of cows and steers that died had left no trace is an enigma." By late summer of 1887, after the summer roundups, the cattlemen were able to make somewhere near accurate appraisals. The Mandan Pioneer estimated the losses for the northern plains at about 75 percent.

In May, Roosevelt was back in New York City. We do not know with any certainty how great his losses were from the winter of 1886-87. The Billings County tax records indicate he paid taxes on 60 percent less cattle in 1887 than in 1886.

The effects of the winter of 1886-87 were also felt in Medora. The De Mores packing plant, which had cut down operations the previous autumn because of the drought, closed for good the summer of 1887. Many of the residents of Medora and Little Missouri then moved to Dickinson. The Medora newspaper, The Bad Lands Cow Boy, also went out of business in 1887, after a fire destroyed the office and press. In 1889 the Dickinson Press reported:

Medora, 18866.Medora had a short season of rapid growth when that charming French nobleman and rather visionary man of business, the Marquis de Mores made it the seat of his slaughtering and beef-shipping enterprise. The big abbatoir is silent and deserted now, and is presumably the property of his creditors. The brick hotel is closed and so is the Marquis' Chateau on the hill and there is small use for the brick church he built. . . .

Medora continued to decline, until it was almost a ghost town. The village of Little Missouri across the river fared worse, and eventually disappeared.

The hard winter had dealt a staggering blow to the open range cattle industry in the Little Missouri Badlands. Most of the outfits which were backed by eastern or foreign capital withdrew from the business. A few managed, however, to hang on without outside financial support. Several big outfits, such as the "Three Sevens," the "Hashknife," and the Huidekopers, continued in business until the end of the century. Pierre Wibaux, unlike most of his contemporaries, bought up the remnants of many of the herds after that harsh winter. By the 1890's he had in the neighborhood of 40,000 head and was one of the largest operators in the United States.

|

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Jan 17 2004 10:00:00 am PDT |