|

FORT SUMTER National Monument |

|

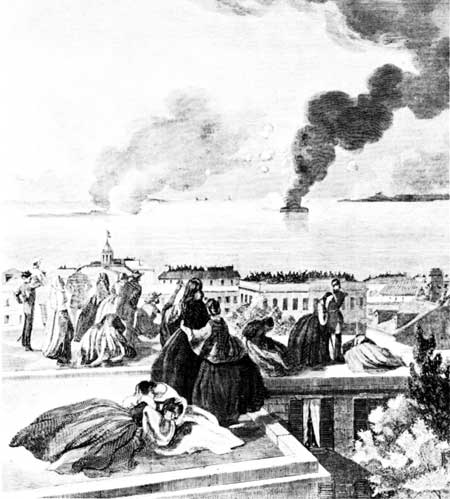

The housetops in Charleston during the bombardment

of April 12-13, 1861.

From Harper's Weekly, May 4, 1861.

AT 4:30 A. M., APRIL 12, 1861, a mortar battery at Fort Johnson fired a shell that burst directly over Fort Sumter. This was the signal for a general bombardment by the Confederate batteries about Charleston Harbor. For 34 hours, April 12 and 13, Fort Sumter was battered with shot and shell. Then the Federal commander, Maj. Robert Anderson, agreed to evacuate; and, on April 14, he and his small garrison departed with the full honors of war. On the following day, President Abraham Lincoln issued a call for 75,000 militia. The tragedy of the American Civil War had begun.

Two years later, Fort Sumter now a Confederate stronghold, became the scene of a stubborn defense. From April 1863 to February 1865 its garrison withstood a series of devastating bombardments and direct attacks by Federal forces from land and sea. Fort Sumter was evacuated only when Federal forces bypassed Charleston from the rear. At the end, buttressed with sand and cotton as well as its own fallen brick and masonry, it was stronger than ever militarily. And it had become a symbol of resistance and courage for the entire South.

Both the "first shot" of April 1861 and the long siege of 1863—65 are commemorated today by Fort Sumter National Monument.

Construction of Fort Sumter

". . . the character of the times particularly inculcates the lesson that, whether to prevent or repel danger, we ought not to be unprepared for it. This consideration will sufficiently recommend to Congress a liberal provision for the immediate extension and gradual completion of the works of defense, both fixed and floating, on our maritime frontier. . . ."

President Madison to Congress,

December 5, 1815

The War of 1812 had shown the gross inadequacy of the coastal defenses of the United States. The crowning indignity had been the burning of Washington. Accordingly, Congress now answered President Madison's call by setting up a military Board of Engineers for Seacoast Fortifications to devise a new system of national defense. Brig. Gen. Simon Bernard, the famed military engineer of Napoleon, was commissioned in the Corps of Engineers and assigned to the Board. Under his unofficial direction, the Board began surveying the entire coast line of the United States in 1817. The South Atlantic coast, "especially regarded as less important," was not surveyed until 1821. One fortification report, covering the Gulf coast and the Atlantic coast between Cape Hatteras and the St. Croix River, had been submitted to Congress earlier that year. Thus, not till the revised form of this report was submitted to Congress in 1826 was the possibility that the "shoal opposite [Fort Moultrie] may be occupied permanently" officially broached. This was the genesis of Fort Sumter. If the location were feasible, reported the Board, "the fortification of the harbor may be considered as an easy and simple problem." With the guns of the projected fort crossing fire with those of Fort Moultrie, the commercial city of Charleston would be most effectively protected against attack.

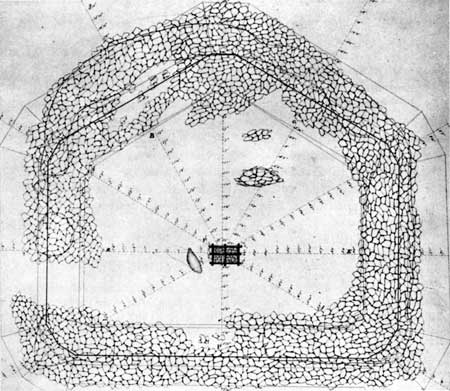

The rock-ring of Fort Sumter's foundation as it looked

4 years after operations were begun.

Courtesy National Archives.

Plans for the new fort were drawn up in 1827 and adopted on December 5, 1828. In the course of that winter Lt. Henry Brewerton, Corps of Engineers, assumed charge of the project and active operations were commenced. Progress was slow, however, and as late as 1834 the new fort was no more than a hollow pentagonal rock "mole" 2 feet above low water and open at one side to permit supply ships to pass to the interior. Meanwhile, it had been named Sumter in honor of Thomas Sumter, of South Carolina, the "Gamecock" of the Revolution.

Late in the autumn of 1834 operations were suddenly suspended. Ownership of the site was in question. In the preceding May, one William Laval, resident of Charleston, had secured from the State a conveniently vague grant to 870 acres of "land" in Charleston Harbor. In November, acting under this grant, Laval notified the representative of the United States Engineers at Fort Johnson of his claim to the site of Fort Sumter. In the meantime, the South Carolina Legislature had become curious about the operations in Charleston Harbor. Late in November, inquiry had been instituted as to "whether the creation of an Island on a shoal in the Channel, may not injuriously affect the navigation and commerce of [Charleston] Harbor Reporting the following month, the Committee on Federal Relations had made the ominous pronouncement that they had not "been able to ascertain by what authority the Government have assumed to erect the works alluded to. . . ." Apparently under the impression that a formal deed of cession to "land" ordinarily covered with water had not been necessary, the Federal Government had commenced operations at the mouth of Charleston Harbor without consulting the State of South Carolina.

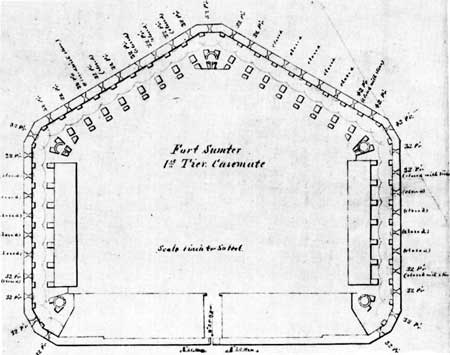

First-floor plan, Fort Sumter, March 1861. The

Gorge (designed for officers' quarters) is at the base of the plan. Gun

casemates line the other four sides. The fort magazines were at either

extremity of the Gorge in both casemate tiers.

Courtesy National Archives.

It was not until January 1841 that work was resumed on the site of Fort Sumter. Laval's claim was invalidated by the State attorney general under act of the South Carolina Legislature, December 20, 1837. But the harbor issue remained and was complicated still further by a memorial presented to the legislature by James C. Holmes, Charleston lawyer, on that same date. Not before November 22, 1841, was the Federal Government's title to 125 acres of harbor "land" recorded in the office of the Secretary of State of South Carolina.

Under the skilful guidance of Capt. A. H. Bowman, the work was now pushed forward. The original plans were changed in several respects. Perhaps the most important modification was with respect to the foundation. Instead of a "grillage of continuous square timbers" upon the rock mass, Bowman's idea of laying several courses of granite blocks was adopted, in the main. Bowman had feared the complete destruction of the wood by worms; and palmetto, which might have resisted such attack, had not the compactness of fiber or the necessary strength to support the weight of the superstructure.

The work was difficult. The granite of the foundation, for example, was laid between high and low watermarks, and there were periods of time when the tide permitted no work to be done at all. Yellow fever was a recurrent problem; so was the excessive heat of the Charleston summers. Much of the building material had to be brought in from the north. The magnitude of the task is indicated by the quantities involved: about 10,000 tons of granite (some of it from as far away as the Penobscot River region in Maine) and well over 60,000 tons of other rock. Bricks, shells, and sand could be obtained locally, but even here there were problems. Local brickyard capacities were small and millions of bricks were required. Similarly, hundreds of thousands of bushels of shells were needed—for concrete, for the foundation of the first-tier casemate floors, and for use in the parade fill next to the enrockment. Even the actual delivery of supplies, however local in origin, was a problem, for then, as now, Fort Sumter was a difficult spot at which to land.

Fort Sumter in December 1860 was a five-sided brick masonry fort designed for three tiers of guns. Its 5-foot-thick outer walls, towering nearly 50 feet above low water, enclosed a parade ground of roughly 1 acre. Along four of the walls extended two tiers of arched gunrooms. Officers' quarters lined the fifth side—the 316.7-foot gorge. This wall was to be armed only along the parapet. Three-story brick barracks for the enlisted garrison paralleled the gunrooms on each flank. At the center of the gorge was the sally port. It opened on the 25-1/2-foot-wide stone esplanade that extended the length of that wall and on a 171-foot wharf.

Fort Sumter was unfinished when, late in December, gathering events prompted its occupation by artillery troops. Eight-foot-square openings yawned in place of gun embrasures on the second tier. Of the 135 guns planned for the gunrooms and the open terreplein above, only 15 had been mounted. Most of these were "32 pounders"; none was heavier. Various details of the interior finish of barracks, quarters, and gunrooms were incomplete. Congressional economies had had their effect, as much as difficulties of construction. As late as 1858 and 1859, work had been virtually at a standstill for lack of funds.

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Dec 2 2002 10:00:00 am PDT |