|

PETERSBURG National Battlefield |

|

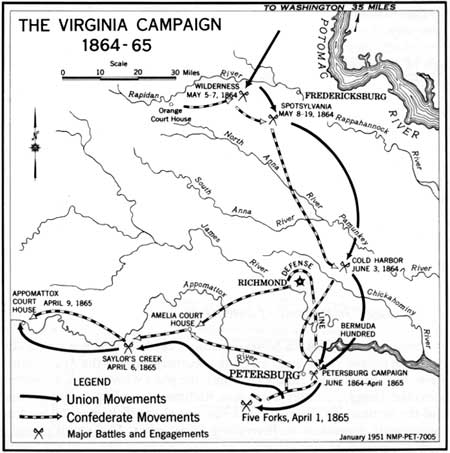

The Virginia Campaign

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

The Union Strategy of 1864

To accomplish the conquest of the Confederacy the Northern plan called for a huge two-pronged attack. Gen. William T. Sherman was in command of the southern prong which was assigned the task of capturing Atlanta, marching to the sea, and then turning north to effect a junction with Grant. Opposed to Sherman was the Army of Tennessee led by Gen. Joseph. E. Johnston.

It was the upper arm of the movement which was directly concerned with Richmond and Petersburg. This was composed of two armies: the Army of the Potomac and the Army of the James. It was the task of these armies to capture Richmond, crush the Army of Northern Virginia, and march south toward Sherman.

The story of the Army of the James in the early phase of the offensive may be briefly told. Gen. Benjamin F. Butler was ordered to advance upon Richmond from the south and threaten communications between the Confederate capital and the Southern States. With some 40,000 Union troops the advance was begun. City Point, located at the junction of the James and Appomattox Rivers and soon to be the supply center for the attack on Petersburg, was captured on May 4, 1864. Within 2 weeks, however, a numerically inferior Confederate force shut up the Army of the James, "as if it had been in a bottle strongly corked," in Bermuda Hundred, a loop formed by the winding James and Appomattox Rivers. Here Butler waited, while north of him the Army of the Potomac and the Army of Northern Virginia engaged in a series of bloody battles.

The Battle of the Wilderness, May 5—7, 1864, began what proved to be the start of the final campaign against the Army of Northern Virginia. Here the Army of the Potomac, commanded by Gen. George G. Meade and numbering approximately 118,000 troops, fought the Confederate defenders of Richmond. Lee had about 62,000 men with him, while an additional 30,000 under Gen. P. G. T. Beauregard held the Richmond-Petersburg area. The battle resulted in a fearful loss of men on both sides, although the armies remained intact. This was followed by an equally heavy series of engagements around Spotsylvania Court House from May 8 to 19.

Failing to destroy the Army of Northern Virginia in these battles, Grant moved the Army of the Potomac to the east of Richmond. It was his hope that he would outflank the Confederate defenders by persistent night marches. Lee was not to be so easily outguessed, however, and after minor battles at the North Anna River (May 23) and Totopotomoy Creek (May 29), Grant arrived at Cold Harbor, about 8 miles east of Richmond. Between him and that city stood Lee's army. On June 3, 2 days after he arrived at Cold Harbor, Grant ordered a direct frontal assault. He was repulsed with heavy losses.

This was the situation at the end of the first month of Grant's campaign:

1. Both sides had suffered heavy casualties. The approximate percentage of casualties to total strength, including reinforcements, was 31 percent for the North and 32 percent for the South.

2. The ability of the Union to refill the depleted ranks was greater than that of the Confederacy.

3. The offensive strength of Lee had been sapped. From the time of the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House until the end of the war, except for local, small-scale actions, the Army of Northern Virginia was a defensive weapon only. This Army, although hurt, had not been crushed, and the Confederate flag still waved over Richmond.

In June, after Cold Harbor, Grant decided to turn quickly to the south of Richmond and isolate the city and the defending troops by cutting the railroads which supplied it. To do this he would need to attack Petersburg.

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Dec 2 2002 10:00:00 am PDT |