|

PETERSBURG National Battlefield |

|

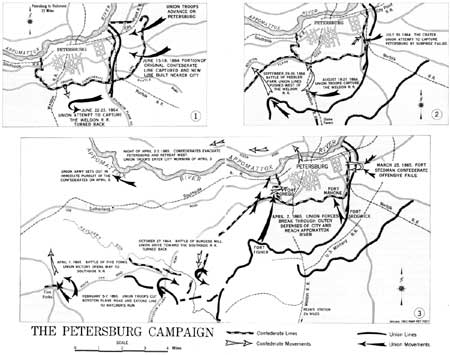

The Petersburg Campaign

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

Union Encirclement Becomes a Reality

The coming of better weather heralded the opportunity for the final blows against the city. Grant, who was now passing some of the most anxious moments of his life, planned that this effort should be concentrated on the extreme right of the long Confederate line which protected Richmond and Petersburg. This meant that hostilities would soon commence somewhere west of Hatcher's Run, perhaps in the neighborhood of Dinwiddie Court House or a road junction called Five Forks which lay 17 miles southwest of Petersburg. On March 24, Grant ordered the II and IX Corps and three divisions of the Army of the James to the extreme left of the Union lines facing Lee. This resulted in a strong concentration southwest of Hatcher's Run. Two days later Gen. Philip Sheridan arrived in City Point, fresh from a victorious campaign in the Shenandoah Valley, and was ordered to join his troops to the concentration on the left. Finally, it began to appear as if the Army of Northern Virginia was to be encircled.

Meanwhile, Lee was waiting only until he collected supplies and rations to last his men for a week and until the roads were passable before leaving to join Johnston. He hoped to leave on or about April 10. The information he received about the rapid accumulation of Union forces opposite his lightly held right was very disturbing, for it not only threatened to cur off his retreat to the west and south, but it also posed a serious danger to the Southside Railroad—the last remaining communication of Petersburg with the south, which continued to deliver a trickle of supplies to the city. So, while Sheridan was assembling his troops around Dinwiddie, Lee issued orders on March 29 which sent Generals George E. Pickett and Fitzhugh Lee to the Confederate right near Five Forks, far beyond Petersburg.

Union soldiers on the ramparts of Confederate Fort

Mahone, April 2, 1865.

Courtesy, National

Archives.

Sheridan was prepared to move against the Confederates with his cavalry on March 30, but heavy rains lasting from the evening of March 29 until the morning of the 31st made a large-scale movement impracticable over the unpaved toads. During the storm he kept his horses around Dinwiddie. On the last day of the month a portion of Sheridan's forces which had pushed northwest toward Five Forks were engaged by Southern forces who succeeded in driving them back toward the main Union troop concentration at Dinwiddie Court House. Pickett, the Con federate leader, then found his men badly outnumbered and withdrew them to Five Forks without pressing the advantage he had gained. This incident, often called the Battle of Dinwiddie Court House, was a minor Confederate victory, although Sheridan's men were neither demoralized nor disorganized by the attack, and Lee could find small comfort in the situation. Lee was able to concentrate on his right only about 10,600 cold and hungry Confederates to meet the expected Union drive to turn his right flank. Massed against him at this part of the line were more than 10,000 Northern cavalry and 43,000 infantry. The desperate urgency of Lee s fears was indicated in the dispatch he sent to Pickett early on April 1, the day of the struggle for Five Forks. "Hold Five Forks at all hazards. Protect road to Ford's Depot and prevent Union forces from striking the south-side railroad. Regret exceedingly your forced withdrawal, and your inability to hold the advantage you had gained."

A Union Army wagon train entering Petersburg.

Courtesy, National Archives.

Throughout April 1, Pickett's troops worked unceasingly, erecting barricades of logs, branches, and earth around Five Forks. At about 4 p. m., with only 2 hours of daylight remaining, Sheridan's cavalry and Warren s infantry attacked. While the dismounted cavalry charged the Confederates from the front of their newly erected defense line, two divisions of foot soldiers from the V Corps drove around to the left of Pickett's troops and, after crossing the White Oak Road which connected Five Forks with Petersburg, hit them on the weakly held left flank. Lacking sufficient artillery support, the Southerners were quickly over come. Realizing that their position was no longer tenable, portions of the Confederate troops tried to retreat to Petersburg, but the avenue of escape had been cut by the Union advance across the White Oak Road.

By dusk, the Battle of Five Forks had ended. Union troops were in possession of the disputed area. They had cut off and captured over 3,200 prisoners, while suffering a loss which was probably less than 1,000.

Now the besieging forces had nearly succeeded in accomplishing Grant's objective of encircling the city. The western extremity of Lee's defenses had crumbled.

Those Confederates who survived the Battle of Five Forks had fallen back to the Southside Railroad where they rallied for a defensive stand, but darkness had prevented a Union pursuit. Grant's troops were within striking distance of the rail line, located less than 3 miles from Five Forks. Lee now knew that Petersburg must be evacuated without delay or the Army of Northern Virginia would be completely cut off from outside help and all possible escape routes would be gone.

The problem of assigning a proper significance to Five Forks is a difficult one. It is now known that Lee and the Confederate government officials were on the eve of the abandonment of their capital. In June of the previous year the Southside Railroad had been a most important objective of the invading army, but the plight of Lee's army had grown so desperate during the intervening months that whether the railroad remained open or not mattered little. Grant, of course, did not know this as a positive fact, although the uncomfortable situation of his opponents was something of which he was doubtless aware. The real importance of Five Forks lay in the probability that, by making it more difficult for Lee to escape, it brought the inevitable a little closer. Brig. Gen. Horace Porter, of Grant's staff, was positive more than 30 years later that news of Sheridan's success prompted the Union commander in chief to issue the orders for the attack that carried the city.

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Dec 2 2002 10:00:00 am PDT |