|

PETERSBURG National Battlefield |

|

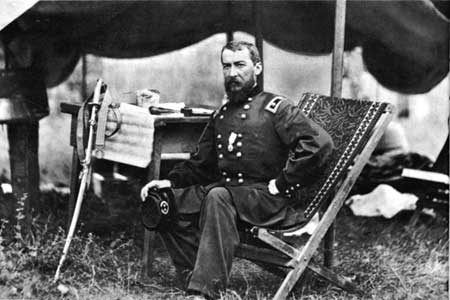

Maj. Gen. Philip H. Sheridan, Union commander

at the Battle of Five Forks.

Courtesy, National Archives.

The Fall of the City

Continuously throughout the night following the Battle of Five Forks, the Union artillery played upon the Confederate earthworks and dropped shells within the city. Troops were prepared for a large general assault which had been ordered for the following dawn. At 4:40 a. m., April 2, 1865, a wide frontal attack was begun with the sound of a signal gun from Fort Fisher. A heavy fog, however, prevented the action from gaining full momentum until after 7 a. m.

The story of the fighting along the Petersburg front on that spring Sunday is one of Union success over stout Confederate resistance. The Union VI Corps, under Gen. Horatio G. Wright, broke through the Confederate right and rushed on to the Southside Railroad. Other elements of Grant's army swept away the remnants of the Confederate lines along Hatcher's Run. Early in the day, Lt. Gen. Ambrose P. Hill, a Con federate corps commander, had been killed by the bullet of a Union soldier near the Boydton Plank Road when on the way to rally his men at Hatcher's Run.

The desperateness of the Southern position was shown when, about 10 a. m., Lee telegraphed President Davis to inform him of the turn events had taken at Petersburg. The message read: "I advise that all preparations be made for leaving Richmond tonight." Davis received the message while attending Sunday services at St. Paul's Church. He left immediately, destroying the calm of worship, in order to prepare for evacuating the capital. The flight of the Confederate government was promptly begun.

By midday the entire outer line to the west of Petersburg had been captured with the exception of Forts Gregg and Baldwin. The city was now completely surrounded except to the north. The left of the Union line finally rested on the bank of the Appomattox River after months of strenuous effort.

It now became apparent to Lee that he must hold an inner line west of Petersburg until nightfall, when it would be possible for him to retreat from the city. While gray-clad troops were forming along this line built on the banks of Old Indian Town Creek, the defenders of Forts Gregg and Baldwin put up a stubborn delaying action against the Northern advance. At Fort Gregg, particularly, there was a desperate Confederate defense. Approximately 300 men and 2 pieces of artillery met an onslaught of 5,000 Northerners. The outcome of the struggle was determined by the numbers in the attacking force, but the capture of Fort Gregg occurred only after bitter hand-to-hand combat. Fort Bald win was forced to yield shortly after the fall of Fort Gregg. The purpose of the defense of these two positions had been accomplished, however, for a thin but sturdy line running behind them from Battery 45 to the Appomattox River had been manned. Temporarily, at least, street fighting within Petersburg had been avoided. Blows directed at this line at other points, such as Fort Mahone near the southeast corner of the defense works, were turned back. Yet there was no doubt in the mind of Lee and other Southern leaders that all hope of retaining Petersburg and Richmond was gone. It was obvious that, if the lines held the Union Army in check on April 2, they must be surrendered on the morrow. The object was to delay until evening when retreat would be possible.

The Crater area. The bank in the background is the

original Confederate earthwork constructed in 1864.

The close of the day found the weary Confederates concentrating within Petersburg and making all possible plans to withdraw. Lee had issued the necessary instructions at 3 o'clock that afternoon. By 8 p. m. the retreat was under way, the artillery preceding the infantry across the Appomattox River. Amelia Court House, 40 miles to the west, was designated as the assembly point for the troops from Petersburg and Richmond.

Grant had ordered the assault on Petersburg to be renewed early the next morning (April 3). It was discovered at 3 a. m. that the Southern earthworks had been abandoned, and so an attack was not necessary. Union troops took possession of the city shortly after 4 a. m. Richmond officially surrendered 4 hours later.

President Lincoln, who had been in the vicinity of Petersburg for several days, came from Army Headquarters at City Point that same day for a brief visit with Grant. They talked quietly on the porch of a private home for an hour and a half before the President returned to City Point. Grant with all of his army, except the detachments necessary to police Petersburg and Richmond and to protect City Point, set out in immediate pursuit of Lee. He left Maj. Gen. George L. Hartsuff in command at Petersburg.

Petersburg had fallen, but it was at a heavy price. In the absence of complete records the exact casualties will never be known, but in the 10-month campaign at least 42,000 Union troops had been killed, wounded, and captured, while the Confederates had suffered losses of more than 28,000. Although the Northern forces had lost more men than their opponents, they had been able to replenish them more readily. Moreover, Grant had been prepared to utilize the greater resources at his disposal, and the Petersburg campaign had been turned by him into a form of relentless attrition which the Southern Army had not been able to stand. The result had been the capture of Petersburg and, more important, of the Southern capital. It had also resulted in the flight of the remnants of the once mighty Army of Northern Virginia.

On the Sunday following the evacuation of Petersburg and Richmond, Lee's troops at Appomattox Court House were cut off from any possibility of uniting with Johnston in North Carolina. In this small Virginia town, nearly 100 miles west of Petersburg, the Army of Northern Virginia, now numbering little more than 28,000, surrendered to the Union forces, Within a week of the fall of Petersburg the major striking force of the Confederacy had capitulated. The Civil War finally was all but ended. Gen. Joseph E. Johnston surrendered his army to General Sherman in North Carolina on April 26, 1865.

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Dec 2 2002 10:00:00 am PDT |