|

FORT PULASKI National Monument |

|

General Lee Returns to Fort Pulaski

The fall of the forts at Hilton Head and Bay Point and the complete rout of the Confederate forces defending them brought panic to Savannah and the adjacent countryside. It was assumed that the Georgia seaport was the real objective of the Federal expedition, and many people, who could afford it, fled to towns and cities in the interior of the State.

At this critical moment Robert E. Lee arrived in Savannah to take charge of the defense. Lee, who had resigned his commission in the United States Army when Virginia seceded from the Union, was now a brigadier general under Confederate colors and had been given command of the forces in South Carolina, Georgia, and east Florida.

The Battle of Port Royal Sound demonstrated to Lee that without adequate naval support it would be impossible to defend the small batteries and forts on the seacoast islands which were all within range of the powerful guns of the Federal fleet. Nor would it be possible to prevent enemy landings on these beach islands without immobilizing thousands of troops for garrison duty, troops that were badly needed in other theaters of war. Even if the manpower could have been spared for island defense, the logistical difficulties of arming and supplying isolated and remote outposts were beyond the capacities of the State or Confederate Governments.

With these considerations in mind, Lee ordered the abandonment of the sea islands of Georgia, the removal of the guns from the batteries, and the withdrawal of the troops to the inner line of defenses on the mainland. This strategy was later confirmed and made the policy of the Confederate Department of War.

On November 10, Tybee Island was abandoned. All batteries were leveled and the heavy guns were ferried across the South Channel to Fort Pulaski. Two companies of infantry from the Tybee garrison were added to the complement at the fort and the remaining troops were withdrawn to Savannah. This was a fateful move for it directly affected the destiny of Fort Pulaski.

At the time, however, no new danger to the fortification on Cockspur Island was anticipated through the abandonment of Tybee Island. It was expected that the fort could defend itself successfully against a naval attack and it was also considered safe from land bombardment. To keep open a line of communications and supply, all side channels leading into the Savannah River above the fort were barred by obstructions. These obstructions, in turn, were protected by floating mines activated by galvanic batteries. The mines, or "infernal machines" as they were called in the naval report, were a new invention which the Confederates borrowed from the Russians. The responsibility for denying the Federal gunboats an opportunity to force a passage through the obstructed side channels into the Savannah River was assigned to Tattnall's flotilla.

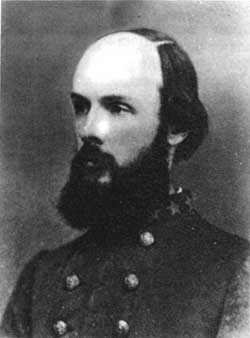

Col. Charles H. Olmstead, who defended Fort Pulaski. Courtesy Miss Florence Olmstead. |

In theory, at least, it should have been possible to hold out at Fort Pulaski indefinitely. When the supply line was finally cut, it was not due to any failure in the plan for the protection of the river, but rather to a lack of vigilance on the part of the Georgia Navy, which permitted the Federals to construct strong batteries in the marshes on the north and south banks of the Savannah between the fort and the city.

Twice during November, General Lee inspected the fort on Cockspur Island and gave minute instructions regarding the manner in which it was to be defended. He foresaw the danger of attack from the rear and ordered certain guns to be mounted on the ramparts above the gorge.

Fort Pulaski celebrated Christmas, 1861, in a big way. The men of the garrison felt snug and secure. In the messes, the tables groaned under the weight of delicacies sent down by friends in Savannah. Eggnog parties were held in many of the casemates. Pvt. John Hart of the Irish Jasper Greens wrote exuberantly in his diary: "Fine day here. Plenty of fighting and whisky drinking."

Ten miles away, in the Federal camp on Hilton Head Island, Christmas was not quite so pleasant. The men were kept hard at work digging entrenchments and unloading captured cotton from a steamboat. When the troops were finally released to enjoy themselves, they had to find their own entertainment. Pvt. Charles Lafferty, of the 48th Regiment of New York Volunteers, wrote his sister: "We had a merry Christmas down hear. We bought sassiges of the nigers and hoe cake and build a fir and cooked our sassiages. That is the way we spent our Christmas."

|

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Mar 4 2002 10:00:00 pm PDT |