|

FORT NECESSITY National Battlefield |

|

The Fort Necessity Campaign (continued)

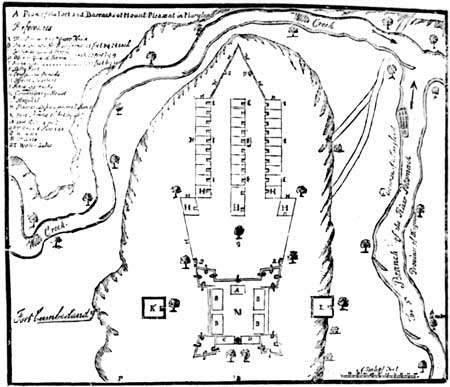

Fort Cumberland, 1755.

From Lowdermilk, History of

Cumberland, Maryland.

PREPARATIONS FOR BATTLE. Governor Dinwiddie realized that in directing an expedition into a wilderness region a strong force of Indians was important for the kind of warfare typical of the frontier. For this support, he turned to the Catawbas and Cherokees of South Carolina. After extended negotiations, in which he had ignored the assistance offered by Gov. James Glen of that colony, Dinwiddie failed utterly.

The loss of this alliance, coupled with the defection of the Shawnee and Delaware tribes soon to occur, was to leave Washington without a single Indian ally in the action at Fort Necessity. Even the Half King, who had long been friendly to the English, now spoke of Washington as "a good-natured man but [who] had no experience" and that "he lay at one place from one full moon to the other and made no fortifications at all, but that little thing upon the Meadow, where he thought the French would come up to him in open field."

The South Carolina Independent Company of regular troops, commanded by Capt. James Mackay, arrived on June 12, but almost immediately difficulties arose over the difference in the rank between Mackay, a regular who held his commission from the King, and Washington, an officer of the militia. Mackay refused to take orders from Washington and then established a separate camp. He also refused to permit his men to work, without additional compensation, on the proposed road to Redstone. In spite of the trouble within his own force, and with the ominous reports that both the Shawnee and Delaware Indians had definitely joined the French, Washington nevertheless decided to press forward with Redstone as his objective.

Leaving the South Carolina regulars at Great Meadows, Washington, on June 16, ordered the Virginia regiment, with nine swivel guns, to move westward over the rugged mountain paths. Upon reaching Gist's Plantation (now Mount Braddock) on June 18, the regiment encountered a band of Mingo, Shawnee, and Delaware Indians. Washington and the Half King, after a long conference, failed to persuade the Indians to hold to the English alliance, and Washington pushed on toward Redstone. On June 28, when the Virginia force, still engaged in clearing the road, was hardly 8 miles from Redstone, Washington learned that a large force of French and Indians was advancing from Fort Duquesne. It was first agreed, in a council of war, to build sufficient entrenchments to make a stand against the French. Captain Mackay and his regulars from Fort Necessity arrived hurriedly on June 29, and, after a second council, it was decided to give way in the face of the strong foe and to withdraw to Great Meadows.

Having lost heavily in horses and wagons in the advance to Gist's Plantation, the return trip over the mountain with baggage and swivels was accomplished only after men and horses alike were completely exhausted. On July 1, after a continuous march, they reached Great Meadows. Many of the men were ill and fatigued. Faced with the danger of being overtaken by the enemy on the march, Washington decided to make a stand at the little stockade. Only a few days earlier he had referred to it, for the first time, as Fort Necessity.

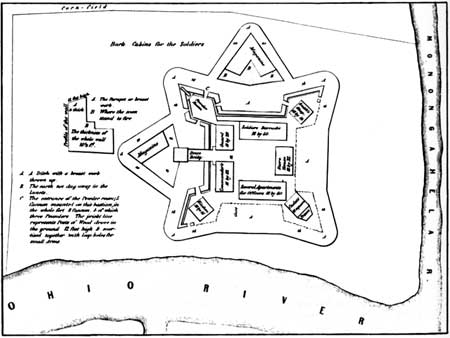

Sketch of Fort Duquesne made by Robert Stobo while a hostage after

the Battle of Fort Necessity

From Sargeant, History of an Expedition Against Fort Duquesne.

In the meantime, at Fort Duquesne the rumor that the English with a force of nearly 5,000 troops were advancing westward had impelled Governor General Duquesne to take measures for the protection of the French fort at the forks of the Ohio. News of Jumonville's death had been dispatched quickly from Fort Duquesne to Montreal. Capt. Louis Coulon de Villiers, brother of Jumonville and an experienced soldier, was commissioned to organize a band of Indians and to proceed to Fort Duquesne. Arriving there on June 26, Villiers found that Contrecoeur, the commandant of the fort, had already formed a detachment of 600 French and about 100 Indians under Chevalier le Mercier to march against Washington. Claiming seniority for the command and requesting the opportunity of avenging the death of his brother, Jumonville, Villiers was given charge of the expedition.

Villiers left Fort Duquesne on June 28, and proceeded to the junction of the Monongahela River and Redstone Creek. Leaving a guard here over his boats and supplies, he began on July 1 the march over the hilly country. Soon the party came upon the uncompleted road which had been abandoned a few days earlier by the English. The force moved slowly and cautiously on July 2 and encamped overnight at Gist's Plantation. At daybreak, July 3, the French again moved forward, in a heavy rain, over the recently built road. Pressing through the drenched forest on the mountainside, pausing briefly at the spot where his brother had been killed and where several bodies still lay exposed, Villiers was soon in the vicinity of the English encampment.

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Dec 2 2002 10:00:00 am PDT |