|

FORT NECESSITY National Battlefield |

|

The Fort Necessity Campaign (continued)

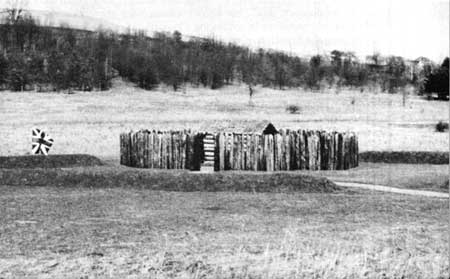

Great Meadows and Fort Necessity from the

southwest, the direction from which the French first approached the

fort.

THE FRENCH STRIKE FORT NECESSITY. Great Meadows was a broad valley through which flowed a small, shallow stream. It was largely marsh land with a heavy growth of tall grass and bushes. On either side of the swale the land rose gradually to ranges of hills. On the southern hill, woodland covered the crest and the slope to a point within 300 yards on the southwest and about 60 yards on the southeast. North of the valley, woodland extended to a line within 250 yards of the creek. It was at the junction of Great Meadows Run and Indian Run, which approaches from the south, that Washington's fort and stockade had been built.

On July 2, the works had been strengthened, and Mackay's men had constructed entrenchments on the exposed southern side of the stockade in order to broaden the defense position, while the Virginians built rifle pits and embankments near the palisades. In the brief time left to Washington for making battle preparations, he had tried to make "the best Defense their small Numbers w'd admit of, by throwing up a small Intrenchm't, which they had not Time to Compleat ..."

Cautiously advancing in mid-forenoon along the Nemacolin Path, under cover of the wooded hills southwest of the fort, Villiers' troops were startled by the firing of a musket. It was one of Washington's sentinels who had given a warning signal that the enemy had been sighted. Within a few minutes, Villiers' men were seen at the edge of the forest.

Unacquainted with the locality, the French at first approached with their flank toward the fort and were fired upon by the swivel guns. "Almost at the same time," Villiers relates, "I noticed the English who were coming toward us in battle array on the right. The savages as well as ourselves shouted the battle cry, and we advanced toward them, but they did not give us time to shoot before they retreated to an entrenchment which belonged to their fort. Then we used all our efforts to surround the fort."

Washington apparently planned at the start to fight a defensive action. His force, now consisting of barely 400 troops, was considerably weakened by the illness of nearly 100 of his men. Part of his force, therefore, was placed in the open ground in front of the entrenchments and, ignoring the first fire of the French, awaited attack in their positions. The French commander failed to draw Washington's men from their stand in front of the entrenchments, and the French force then shifted to the right where "they advanced irregularly within 60 yards of our Forces, and y'n [then] made a second discharge."

Washington, observing that the French did not intend to attack his men in the open field, now ordered them to withdraw to their trenches and reserve their fire until the expected attack upon these defenses. Finding that the French still would not make an attempt against his men in the trenches, Washington ordered them to fire. "We continued this unequal Fight," he relates, "with an Enemy sheltered behind the Trees, ourselves without Shelter, in Trenches full of Water, in a settled Rain, and the Enemy galling us on all Sides incessantly from the Woods, till 8 o'Clock at Night ..." At the start of the battle, declared John B. W. Shaw, a member of the Virginia regiment, as the Indians ventured forth from the cover of the trees, Washington ordered his men to fire and at the same time two swivel guns were discharged, the combined volleys killing many of the Indians. "After this," he states, "Neither French nor Indians appeared any more but kept behind Trees firing at our Men the best part of the Day, as our People did at them."

Mercier suggested in the evening that Villiers "pen up the English in their fort during the night and prevent their coming out at all." At about 8 o'clock, however, the French leader, having strengthened his own positions, called to the English that he was willing to negotiate. "We had endured rain all day long and the detachment was very tired," Villiers later noted in his journal. Since the savages "were making known that their departure was set for the next day, and since it was reported that drum-beating and cannon shot could be heard in the distance . . . .", the French commander apparently decided to take the initiative in requesting a cessation of hostilities.

On hearing the French commander call for a truce, Washington was at first hesitant, stating at a later time ". . . we looked upon this offer to parley as an artifice to get into and examine our trenches and refused on this account until they desired an officer might be sent to them, and gave their parole for his safe return. . . ." Upon being assured by this pledge of safety, however, Washington agreed to send two officers, Jacob Van Braam and William Peyronie, to see Villiers. At the meeting in the open meadow between the lines, Villiers informed Van Braam and Peyronie that the French desired to avoid war and stated that their only mission was to avenge the death of his brother Jumonville and to compel English settlers to vacate lands claimed by the French Crown.

In the terms of capitulation handed to Van Braam, Washington was permitted to return to his own country with his entire force, except two captains, Robert Stobo and Van Braam, who would be held as hostages for the safe return of French prisoners captured in the action on Chestnut Ridge. Of the equipment, only the cannon were taken from them. Although Governor General Duquesne had consistently maintained that the English had never held a proper claim to lands west of the mountains, Villiers inserted a clause stating that the English were to agree not to construct any defense work west of the mountain range for the period of a year.

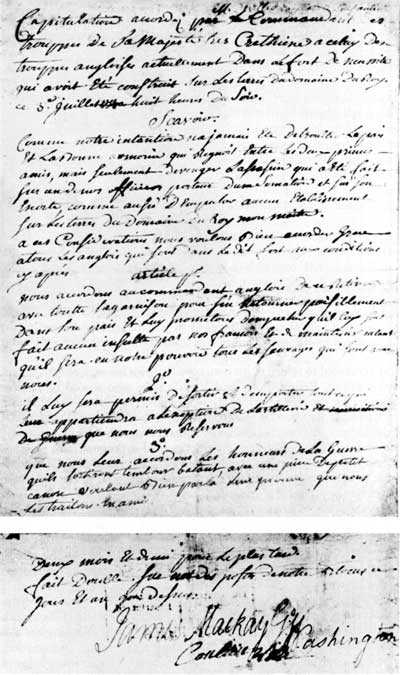

Facsimile of the first page and signatures of the

Articles of Capitulation at Fort Necessity.

Courtesy Department

of Civil Statutes and of Archives, Superior Court, Montreal,

Canada.

This was the substance of the articles of capitulation brought to the fort by Van Braam and examined by Washington. Capt. Adam Stephen later described vividly the manner in which the terms were received. Referring to Van Braam's report on the articles, he wrote: "It rained so heavily that he could not give us a written Translation of them; we could scarcely keep the Candle light to read them; they were wrote in a bad Hand, on wet and blotted Paper so that no person could read them but Van Braam who had heard them from the mouth of the French Officer ..." The articles which Washington unwittingly signed referred to Jumonville's death as an assassination. The combination of poor light and Van Braam's meager knowledge of French led him to translate the word orally as "death". Washington was greatly mortified when the error was discovered as the terms were widely circulated in Europe and it was made to appear that he had admitted an assassination. If he had received an accurate translation, he certainly would not have signed it. Every officer present, according to Captain Stephen, was willing to declare that "there was no such word as Assassination mentioned; the Terms expressed to us were the death of Jumonville.'"

The capitulation arranged, Washington's survivors prepared to leave, early on July 4, a field on which his little force had fought the strong detachment of French and Indians on equal terms and under trying conditions. Relating that his own losses were 30 killed and 70 wounded, he estimated that 300 of the French and Indian force were killed and many more wounded as the enemy were "busy all Night in burying their Dead, and many yet remained the next Day." Villiers reported a loss of only 20, but another participant, Varin, listed them as 72.

The English force was soon on the homeward journey. The horses and cattle had been killed. The men who were able had to carry the sick and wounded. Harassed by the Indians on the march, they finally reached the base at Wills Creek 50 miles away. As the English band started on its way, Villiers' force "demolished their fort, and M. le Mercier had their cannons broken up . . ." a statement which is partially corroborated by that of Colonel Innes at Wills Creek, which notes that "after the capitulation the French demolished the works."

Villiers, having completed his mission of driving the English back across the Alleghenies, retraced his path to Redstone and thence by way of the Monongahela to Fort Duquesne which he reached on July 7.

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Dec 2 2002 10:00:00 am PDT |