|

LITTLE BIGHORN BATTLEFIELD National Monument |

|

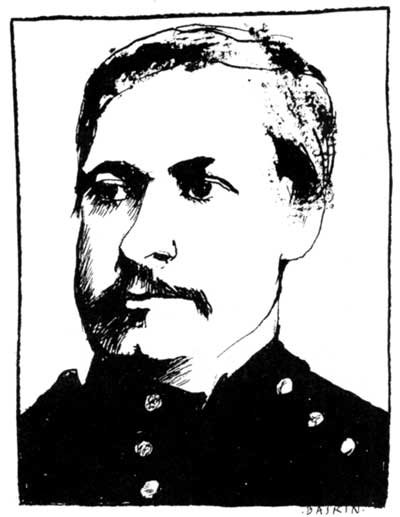

Maj. Marcus A. Reno.

Indian Movements

From General Sheridan down to the newest lieutenant, the great worry was that the hostiles would evade the columns sent after them. Rarely, unless absolutely certain of victory, did the Plains Indian stand and fight; usually he faded into the hills and easily eluded his slow-moving pursuers. Thus military planning focused mainly on how to catch the quarry rather than on how to defeat him once caught. Sheridan's plans assumed that each of the converging columns could alone handle any gathering of hostiles it succeeded in bringing to battle. In all the unceded territory, according to the Indian Bureau, the warrior force did not exceed 800, and the possibility that these might unite in one place was not seriously considered.

As a matter of fact, a great many more Indians were absent from their agencies than the Bureau had reported, and they continued to flock to Sitting Bull's standard throughout the spring. By June the scattered bands had begun to come together in a single village that formed one of the largest in the history of the Great Plains. All the Teton Sioux were represented—Hunkpapas under Sitting Bull, Gall, Crow King, and Black Moon; Oglalas under Crazy Horse, Low Dog, and Big Road; the Miniconjou followers of Hump; Sans Arc, Blackfoot, and Brule Sioux. There were also Northern Cheyennes under Two Moon, Lame White Man, and Dirty Moccasins, and a handful of warriors from tribes of Eastern Sioux. They clustered around six separate tribal circles, and altogether they numbered perhaps 10,000 to 12,000 people, mustering a fighting force of between 2,500 and 4,000 men. Many had firearms—some the Winchester repeating rifle obtained, quite legally, from traders and Indian agents for hunting.

Secure in their unaccustomed numbers, the Sioux and Cheyennes, moving up Rosebud Creek in mid-June, wasted little thought on the news brought by some young men that they had seen soldiers farther south, beyond the head of the Rosebud. Turning west, the great procession crossed the Wolf Mountains and came to rest on a tributary of the Little Bighorn later named Reno Creek. Here further reports confirmed the presence of many soldiers descending the Rosebud, and more than a thousand warriors rode over the mountains to contest the advance.

On the morning of June 17, General Crook collided with this array, and after a severe action lasting most of the day he turned about and marched back to Goose Creek (near present Sheridan, Wyo.) to call for reinforcements. The Indians returned to their tepees in triumph and at once moved down Reno Creek, crossed the Little Bighorn, and laid out a new camp. It lined the west bank of the river for 3 miles and sprawled in places all the way across the mile-wide valley.

The Battle of the Rosebud infused the Indians with confidence. And well it might, for it had thrown back one of Sheridan's columns and prevented its juncture with the others. Of the proximity of the others, however, the hostiles had no knowledge, while of their location the military commanders had formed a nearly correct idea. On the very day of the Battle of the Rosebud, Major Reno had examined the broad Indian trail in Rosebud Valley, and even as the Sioux and Cheyennes moved their village to the Little Bighorn, Terry, Gibbon, and Custer laid plans to smash it.

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Sep 28 2002 10:00:00 pm PDT |