|

LITTLE BIGHORN BATTLEFIELD National Monument |

|

Plan of Action

On the evening of June 21 General Terry gathered his principal subordinates in the cabin of the Far West, moored to the bank of the Yellowstone at the mouth of the Rosebud, and worked out the details of a strategy that had already formed in his mind for snaring the Indians whose trail Reno had seen in the Rosebud Valley. Two fundamental assumptions shaped this plan: that the enemy probably numbered less than a thousand warriors, and that unless surrounded and forced into battle they would flee to the mountains as soon as they discovered the approach of soldiers. Although General Crook had learned that Sioux strength and will to fight had been grossly underestimated, word of his recent setback had not yet reached Terry. Terry's information indicated that the hostile camp almost certainly lay somewhere in the Little Bighorn Valley. By maneuvering Custer into position on one side and Gibbon on the other, he hoped to box in the Indians and force them into battle. Accordingly, Custer would lead his regiment up the Rosebud, cross to the Little Bighorn, and drop down that stream from the south; Gibbon, accompanied by Terry and his staff, would march back up the Yellowstone, ferry to the south bank, ascend the Bighorn, and enter the Little Bighorn Valley from the north.

Although recognizing that uncertainties of terrain and enemy location would prevent close cooperation, Terry hoped that no action would be precipitated before June 26—the earliest day Gibbon's foot soldiers could reach the objective. To afford Gibbon the needed time and to satisfy himself that the quarry had not slipped out of the trap to the southeast, Terry intended for Custer to continue up the Rosebud beyond the point where the hostile trail turned west and not veer toward the Little Bighorn until he had passed the head of the Rosebud.

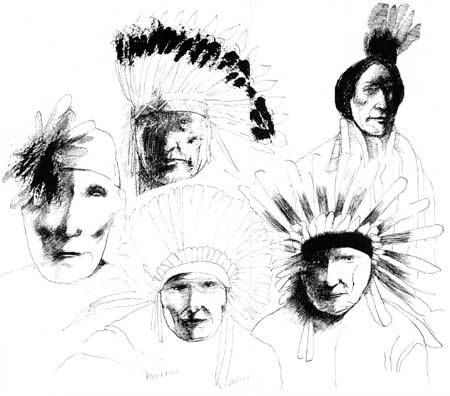

Terry fully understood that Custer's cavalry, with no infantry to hold it back, enjoyed a much better chance of striking a blow than did Gibbon. For this reason he let Custer have six of Gibbon's Crow Indian scouts, who knew the country better than the Arikaras, and also offered to send along Gibbon's battalion of the 2d Cavalry under Maj. James Brisbin, as well as the Gatling gun battery. Custer gratefully accepted the scouts but declined the additional cavalry and the artillery. The Gatlings, he said in truth, would slow his march; Brisbin's cavalry, he explained less plausibly, would not enable him to overcome any opposition that the 7th alone could not cope with.

The next morning, June 22, Terry outlined his views to Custer in writing. Before sketching in general terms the troop movements that had been decided upon, the general noted the impossibility of giving definite instructions, and he professed, anyway, to repose too much confidence in his subordinate's "zeal, energy, and ability" to attempt to lay down detailed orders "which might hamper your action when nearly in contact with the enemy." Custer should conform to Terry's views, therefore, unless he saw "sufficient reason for departing from them." Depart from them he did. Whether sufficient reason existed has ever since been a topic of heated controversy.

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Sep 28 2002 10:00:00 pm PDT |