|

LITTLE BIGHORN BATTLEFIELD National Monument |

|

Chief Gall.

March to the Little Bighorn

At noon on June 22 the 7th Cavalry passed in review for Terry and, behind the buckskin-clad Custer, began the march up the Rosebud. The column numbered 31 officers and about 585 en listed men, 40 Indian scouts, and nearly 20 packers, guides, and other civilian employees. Each trooper carried 100 cartridges for his carbine and 24 for his pistol, and a mule packtrain trans ported another 50 rounds of carbine ammunition per man together with rations and forage for 15 days.

Amid clouds of choking dust, Custer's column pushed up the Rosebud. On the 23d it struck the hostile trail, which through out the afternoon and all next day grew rapidly fresher and larger. In the broad trail and the proliferation of abandoned campsites, the Crow and Arikara scouts saw evidence of a great many more Indians than Custer and his officers suspected—perhaps several thousand—and they made no secret of their misgivings over being drawn into a fight with such an array. Although Custer thought the scouts inclined to exaggerate, he had raised his own estimate of enemy strength to 1,500 warriors, a force he judged his regiment well able to handle. A different fear gripped him, as it had everyone from the beginning of the campaign—that the Sioux would escape if given a chance. Impelled by this likelihood, he pushed the column hard—from 12 miles on the 22d to 30 each on the 23d and 24th. By the evening of the 24th, he had reached the point where the trail bent to the west and ascended the divide between the Rosebud and Little Bighorn Valleys. Indian "sign" left little doubt that the Sioux village lay just over the mountains.

Here Custer made a crucial decision. Instead of continuing up the Rosebud as Terry desired, he would follow the trail nearly to the summit of the divide, spend the 25th resting his exhausted command and fixing the location of the hostile camp, then hit it with a dawn attack on the 26th, the date appointed for Gibbon to reach the mouth of the Little Bighorn.

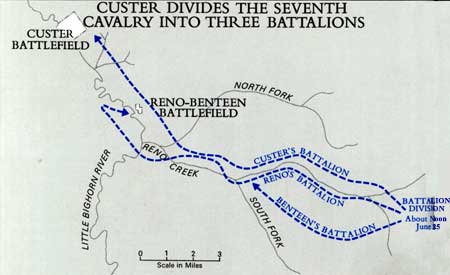

Custer Divides the Seventh Cavalry into Three Battalions.

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

A night march, adding 10 miles to the 30 already covered during the day, carried the regiment nearly to the summit. At the same time, Lt. Charles A. Varnum and several of his scouts climbed a high hill to the south, known as the Crow's Nest, and at dawn scanned the wrinkled landscape stretching off to the Bighorn Mountains. Some 15 miles to the west, where a thread of green traced the course of the Little Bighorn, the Crows discerned smoke rising from the Sioux village and on the benchland beyond a vast undulating mass that represented the Sioux pony herd. Lieutenant Varnum could not see these things, and neither could Custer when he arrived in response to a message from the lieutenant.

Although doubting that his scouts had actually detected the village, Custer knew it could not be far off. Moreover, his worst fears at once seemed confirmed, for two small parties of Sioux were spotted during the morning. Unquestionably, the regiment had now been discovered. If action were delayed until the 26th as planned, there would probably be no Indians to attack. And so Custer made his second crucial decision—to find the village and strike it as soon as possible.

For his decisions on the evening of the 24th and the morning of the 25th, Custer's detractors, pointing to his burning pride in the 7th Cavalry and his reputation as an impetuous commander, have charged him with willful disobedience of orders springing from a blind determination to win all the glory. He failed to meet Terry's desire that he continue up the Rosebud beyond the point where the Indian trail left it before turning to the Little Bighorn, then rushed his exhausted command into battle a day early and without first ascertaining the location and strength of the enemy.

Custer's defenders have replied that Terry's instructions were not binding, that the hostile trail clearly revealed that the Sioux were so close that they could not possibly have slipped off to the southeast, and that to continue the march up the Rosebud would not only have been pointless but might have afforded them the opportunity to escape. Once the regiment had been discovered, moreover, there was no other proper decision than to attack, for the enemy could hardly have been expected to remain in place waiting until the soldiers found it convenient to fight.

A good case can be made for either point of view, and the imponderables insure that men will always arrive at different answers. The command decisions that brought on the Battle of the Little Bighorn will doubtless continue to form fascinating topics of debate.

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Sep 28 2002 10:00:00 pm PDT |