|

OCMULGEE National Monument |

|

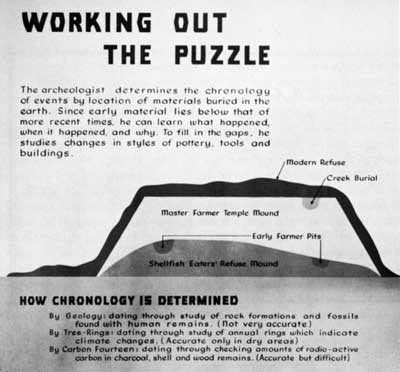

Museum exhibit panel. Arrangement of cultural features

idealized.

The American Indian

Every school boy knows that at the time of its discovery North America was the Red Man's continent. He knows that white people, equipped with the weapons and knowledge of an advanced civilization, took this land by persuasion or by force. For most of us our knowledge of the American Indian begins and ends with the brief interval in time where these two races were involved in a bitter struggle.

Our knowledge is limited because until recently no one really knew the answers to such questions as "Where did the Indian come from ?" Many thought that he had been preceded by another race of superior intelligence, the "Mound Builders"; and in general our information about him had rested on a great deal of ingenious speculation with very little actual knowledge to back it up. The people most actively interested in the problem are the archeologists. They have been studying it intensively for about 75 years; and, while their work was at first mostly descriptive, the last 25 years have seen tremendous strides in both the techniques of their research and the soundness of their interpretations. Now we know a good deal about the Indian and have traced his career on this continent back to a time when our own past becomes almost equally dim and shadowy. But this information is still mostly to be found in big books, or in special studies that are hard to obtain; so it may be helpful to outline briefly here what we know today of the origins and early career of this particular branch of the human race.

In the Old World, human history has been traced to its beginnings through fossil remains suggesting a stage of development earlier than man. In the Western Hemisphere, however, no such remains have been found, which indicates that the American Indian must have immigrated here from another continent. In searching for his closest relatives, therefore, scientists are now agreed that certain physical peculiarities show the modern as well as the prehistoric Indian to be most closely linked to the peoples of eastern Asia.

Cross section, east slope of Funeral Mound, Ocmulgee National

Monument. Arrangement of construction elements confused by erosion and

wash from top and side of successive mound stages.

Most living American Indians share with the east Asians a group of features which are considered to be distinctive of the great Mongoloid division of mankind. These include: straight dark hair, dark eyes, light yellow-brown to red-brown skin, sparse beard and body hair, prominent cheekbones, moderately protruding jaws, rather subdued chin, and large face. Since the question of race determination, however, is one of extreme complexity, it should also be pointed out that while the majority of modern Indians as well as prehistoric skeletal remains in America share enough of these features in common to be regarded as predominantly Mongoloid, they as well as the east Asians themselves, possess other physical traits like stature and head form which vary widely from group to group. Some of these other traits may be explained by the influence of different environments acting over long periods of time, but others point to an admixture of non-Mongoloid features in some of the earliest migrants to these areas. It is just the meaning of this mixture of apparently diverse elements which makes the problem of ultimate origins so difficult; and we shall have to be content for now with the general relationship which seems to have been established. If the earliest wanderers to the Americas were primarily a blend of other racial elements, their influence on the physical type of later American Indians has been largely submerged by the Mongoloid features of the vast majority of later arrivals.

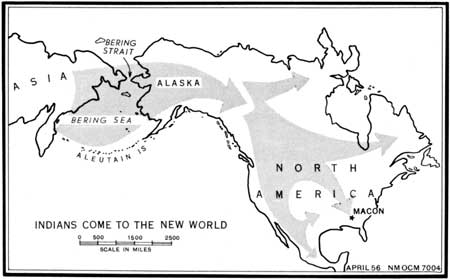

Asia, too, is the closest great land mass to this continent, and from it there are more practicable means of access than from any other area. Even today the Bering Strait could be crossed by rafts, for islands at the middle cut the open water journey into two 25-mile stretches. Eskimos make the trip in their skin boats, or in winter by dog sled over the frozen surface of the strait. In the past, the journey must have been even simpler. During the several worldwide glaciations of the Pleistocene Epoch, a geological period which began more than 600,000 and ended about 10,000 years ago, great masses of ice spread across the surface of the continents in the higher latitudes. Since the growth of these ice sheets was nourished by falling snow, the seas, which supplied the necessary moisture, were reduced in volume as the ice expanded. The maximum drop in sea level has been calculated as between 200 and 400 feet, but the floor of Bering Strait is so shallow that a drop of as little as 120 feet would have been sufficient to create a dry land bridge between the continents. Further lowering must have increased the area and elevation of this passage, but the main effect of this was simply to extend the length of the interval during which the bridge remained open. This may have continued well into the period of milder climate after the time of maximum ice advance.

Another peculiar condition in this region at this time was the presence of considerable areas untouched by glacial ice. These included the foothills and coastal plain along Alaska's northern coast as well as the great central Yukon Valley. This surprising situation was probably due to the small amount of moisture left in the winds which had passed over the high and cold mountain chains bordering the southern coast and the second great mass of the Brooks Range to the north. Furthermore, the broad Mackenzie Valley, leading south along the eastern slopes of the Rockies, was the area latest to be covered by glacial ice and first to open up with the return of warmer conditions. It may even be that the ice failed to cover this region during the last one or more of the minor advances which together make up the latest, or Wisconsin, glacial period.

Taken all together, therefore, the conditions described provided man with a chilly but relatively dry and passable route from the Asiatic mainland to Alaska and thence to the warmer interior sections of North America. For a considerable period this route must have been flanked with glacial ice lying only a few miles away on one side or both through a total distance of some 2,000 miles. It is one of man's distinctive qualities, however, that he is able to adapt himself to extremes; and it is probable that the game he lived on was itself acclimated to living close to the edges of the ice sheets. We are less certain about the conditions under which this journey was begun at its Asiatic end; but it seems likely that there, too, ice would have formed in the high mountain masses, but that the valleys and lowland would have remained open as they did farther east.

We are confident in our knowledge of where man came from to the New World and how he was able to make the trip. We are on less certain ground, however, when we try to determine when he arrived. Estimates have varied widely, changing with every increase in our knowledge. From the first enthusiastic attempts to fit the Indian into the Old Stone Age chronology which was just then unfolding for the Old World, the cold reasoning of skeptical scientists brought down the maximum age of human occupation of this hemisphere to some thing like 3,000 years. Beginning in 1925, however, a series of finds has provided unquestionable evidence that men using very distinctive weapons were living on this continent, largely by hunting the mammoth and a great bison, both now extinct, during the period when the ice was receding for the last time. The typical channeled or fluted spear point of this people has even been found lately along the northern Alaska coast. So, while we still cannot say that this characteristic artifact was brought from Asia rather than being developed here in America, it is at least an interesting coincidence that man hunted large and now extinct game in Alaska in areas where conditions were at times particularly well suited to his immigration.

Other evidence shows that the users of this telltale point were not the first to live in the region of the western plains; at least some of their numbers had been preceded by men whose stone work was almost as unusual and equally easy to identify. Recently developed methods of dating by the use of radioactive carbon—14 show that the span of time when the channeled point users, Folsom man, roamed the Plains included one date of about 8000 B. C. For his predecessors, we feel justified in pushing this date a good 2,000 or 3,000 years further back; and there are even hints taken quite seriously by leading archeologists that man was here many thousands of years before that. We know that the great climatic swings marking the principal stages of the Pleistocene Epoch were actually composed of repeated lesser pulsations. Like a mighty pump, the changing climate worked upon all life within thousands of miles of the shifting ice fronts, driving it southward with icy winds and then sucking it back toward the north as cold and damp were replaced by heat and drought. Man followed the game; and this, rather than any planned migration, probably accounts for the wide spread of his earliest remains.

American Indians, then, are most closely related to the present inhabitants of eastern Asia, where they, too, had their origin. They came to this country as its first human inhabitants some 12,000 to 15,000 years ago at the very least. They did not come all at once, or even in one limited period of time, but probably in a fairly continuous succession of small hunting bands following the game. Their earliest migrations hither were doubtless the indirect result of great fluctuations in climate which marked the coming and going of the ice during the glacial age; and it was the peculiar conditions existing about the present region of Bering Strait that encouraged them to explore the now accessible region to the east. Once they had reached the New World, their hunting travels probably carried them back and forth in both directions so that a knowledge of the seemingly limitless territory beyond became fairly general.

Above: Broken Clovis point and sharp-cornered scrapers

from Ocmulgee excavations. Point length 3-11/16 inches. Right: Artist's

reconstruction of point.

The disappearance of the land bridge must have been very gradual by human standards. Successive generations would have found the journey increasingly difficult, but this would only have led to the adoption of other measures such as waiting for winter ice or the use of rafts or boats to cross the widening stretches of open water. Once arrived, they began to spread out over the country, moving on as the game became scarce to where it was more abundant, looking for new and unpeopled areas whenever they began to catch sight too often of members of other bands hunting the same territory. Not many years would be needed to cover the vast expanse of the two continents. With movements of only 20 or 30 miles each year, it might have happened in as little as a dozen generations; but we can say for sure that man had reached southern Patagonia by about 6000 B. C., possibly far earlier. By then, we may assume, the new homeland had been explored with some thoroughness; and portions of it had already been inhabited for thousands of years. It was by no means filled up; but many of its potentialities were known, and American Indians were well started on their own peculiar course of development.

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Dec 2 2002 10:00:00 am PDT |