|

OCMULGEE National Monument |

|

Mammoth Hunters, from Museum exhibit panel.

Man Comes to Georgia

The roving existence led by these Wandering Hunters brought them into the region which is now Georgia at a relatively early date. We do not know by what route they came here, for it is easier to seek out the geographic limitations which restricted the first migrants to the New World to a single point of entry than it is to trace the wanderings of their descendants over some 8,000,000 square miles of North America. Nevertheless, we are beginning to get a few hints.

Fluted point sites have been found in Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, and Virginia; and single fluted points have been found in a number of places in Georgia, though possibly more often north than south of Macon. One fluted specimen, however, was actually excavated from the Macon Plateau, a designation adopted for the hilltop terrain of the Ocmulgee excavations. The recovery here of other tools of the same greatly decomposed flint strengthens the likelihood of a true "paleo-Indian" occupation at Ocmulgee. The inclusion among them of many thumbnail scrapers of a type recently shown to be distinctive of eastern fluted point sites is especially significant.

The fluted point, missing the forward one-third of its length, was a fine specimen of the so-called Clovis type of these artifacts, and so typical of thousands of such implements which have been picked up at random in the eastern United States as well as in the West. The Clovis point is like its Folsom cousin in several ways, particularly in having a long channel flake removed from one or both of its faces, possibly as a means of reducing its total thickness, and in the grinding of the edge along the lower sides and across the base to avoid cutting the lashings which bound it to the shaft. Like the smaller Folsom point, too, it is named for a site in the western High Plains, where its position underlying Folsom on some sites and its association with mammoth bones give us definite clues to its age west of the Mississippi.

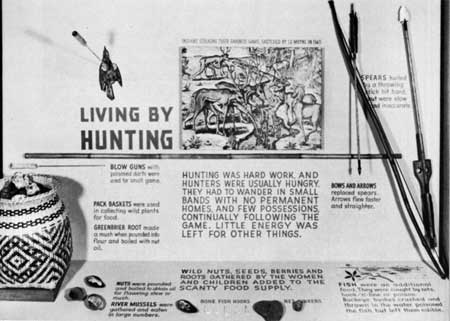

Hunting was hard work. Museum exhibit case.

Unlike Folsom, however, the Clovis fluted point is not limited to the region on the east flank of the Rockies. Instead, it has been found from Alaska to Costa Rica and from Vermont to Florida. Its use, too, seems to have been less specialized. Folsom man was a bison hunter; and the abundant grasses of the Plains probably account for the rather definite limits of his range. The big Clovis points, on the other hand, were certainly used on mammoth; but we do not know that this oversized quarry was their only target. Possibly the mammoth was more adaptable than the bison and could seek out other areas as the changing climate made its accustomed haunts unlivable; or it may have been the Clovis hunters who were the more flexible and could shift more readily to other kinds of game when the mammoth disappeared from the scene.

The wide geographic range of the point is matched by the variety of shapes which are included in the type, though all have a family resemblance built around the distinctive channel formed on one or both faces. Until it is found in a context permitting direct dating, however, the real problem in the East hinges on the significance of this family resemblance. The question is whether this resemblance is a result of chance, or whether it indicates contact with the makers of the fluted points in the West whose age is now reasonably well established.

Perhaps the only thing we can say definitely about these early nomadic hunters would be that their unusual fluted type of projectile point occurs in the eastern United States and has been found in clearly defined contexts which suggest a greater age than that known for any other recognized types in these areas. This distinctive weapon is thought to be a variety of the western Clovis fluted point, which has been found in the West beneath Folsom, and therefore antedating 8000 B. C.

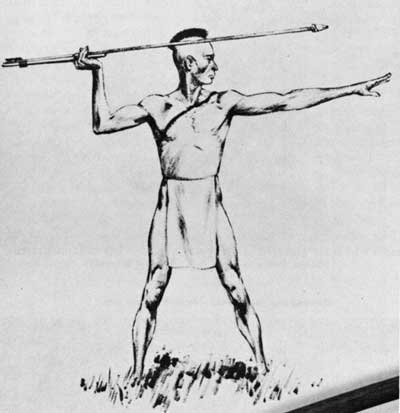

Hunter with atlatl (throwing stick).

Their simple living was obtained with the aid of a few tools and weapons of stone and wood. Being constantly on the move, they could erect no very permanent dwellings; and a rough lean-to shelter was doubtless their only protection from the elements. Hunting was the major activity of the men; for, with fish from the streams, the game which they killed made up the chief element of their diet. The women were not idle, however; for in addition to preparing the food and caring for the children, they spent many hours in gathering the nuts, roots, and berries which made such a necessary and welcome supplement to their daily fare. It is doubtful that the bow and arrow, which to us are almost inseparable from our picture of the Indian, had yet been invented; but the thrusting spear and the thrown javelin were very effective at close range. At greater distances the hunter could bring down his game with the dart propelled by a throwing stick. This increased the effective length of his arm and imparted the resulting greater thrust to the butt of the shaft.

Also missing in their equipment were the pottery cooking vessels of the later Indians, which so simplified the preparation of foods by boiling and thus added variety to the menu. Stone boiling, of course, could be accomplished by means of heated rocks dropped into some suitable container, such as a pit in the ground lined with a skin; but the method was tedious and probably less used for that reason.

Organization for such a life was simple. Since they must move with the game on which they depended, group size had to be limited; for large bodies of people could not move easily from place to place. Moreover, the population was not large, and there was plenty of room to spread out. For all these reasons the hunting band was probably made up of a few related families, numbering on the average perhaps 50 people who habitually camped together. Leadership in such a small group would not be a matter of too great importance; and the chief might be chosen for skill in hunting or for an outstanding personality. Possibly he inherited the office, but in any case his authority is not likely to have been very great. The band doubtless accepted his choice of campsite, his direction in the hunt, or arbitration in disputes; but in doing so it was more likely to be out of respect for his ability than in recognition of his official position.

Even at this simple stage of culture, though, there were doubtless well defined rules of conduct. All primitive peoples today share certain universals of social life. From these we may confidently infer that every man was part of a clearly defined kin group, that the structure and relationships of this group determined into what similar group he might marry, and which were forbidden to him as sources for choosing a mate. We can also be reasonably certain that while antisocial acts like murder, adultery, and theft might not be punished by the community at large, strong measures to hold them in check were generally approved even though they might have to be initiated privately. In short, the rudiments of social living were already thousands of years old. The lives of these early Georgians were different from our own in countless material ways; but even at this early date their primary problems were the same as ours. They must have food, shelter, and protection for individual survival; and the continued existence of the group required the education of its younger members in the skills and habits and community organization of their elders. The means to these ends were crude, and by our standards extremely simple; but they were not developed without considerable ingenuity; and hard work made up for many technical shortcomings.

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Dec 2 2002 10:00:00 am PDT |