|

OCMULGEE National Monument |

|

Shellfish Eater campsites were gradually raised on mounds of their

own shell refuse, sometimes even larger than this.

Courtesy Florida Board of Parks and Historic Memorials.

Food From the Waters

Our knowledge starts to increase as we come to the period beginning about 5,000 years ago. Here a few of the details of Indian life in the Southeast emerge rather clearly. Curiously enough it was the food habits of these Shellfish Eaters which first led to their identification; and even today our scanty information on them still tends to center around this feature of their lives. From the nature of the evidence we will soon present, it is easy to infer that the principal food of many of the groups of this period was shellfish. This may not seem especially remarkable; but we know that, in shifting to a principal reliance on the lowly mussel, clam, or oyster, they accomplished, in effect, a local revolution in man's pattern of living. They had discovered that an almost inexhaustible supply of these prolific creatures was to be had for the taking in places along the rivers and the ocean shore where conditions favored their growth. Perhaps the taste for this form of diet was difficult to acquire, but once achieved it freed them for generations from the hard necessity of moving their camp every time the game grew scarce. At last they could settle in one place; and the numerous sites they occupied tell us not only that life was easier but that the abundant food supply contributed also to a marked increase in the population.

Dart points of the shellheap dwellers were

heavy but workmanship varied from crude to very careful. Length,

2-1/4 to 2-7/8 inches.

Our chief reminder of the presence of these early shell gatherers lies in the piles of shells which mark the scene of their activities. Of course the bones of deer, bear, rabbit, turkey, and other wildlife mixed with the shells show us that to vary their diet they did a good bit of hunting and fishing as well. The river and coastal shorelines are dotted with such refuse heaps, often of monumental size, from Florida to Louisiana and northward inland to the Ohio River and along the coast as far as Maine. It may be doubted that these were all produced by related peoples, or that they even represent the same time period; for it is certain that many of them were still growing in fairly recent years. Still, the fact remains that in the southern area as far north as Kentucky and Tennessee the sites represent the oldest camps yet to be uncovered following the earlier paleo-Indian period; and that besides the evidence of a remarkably uniform economy, they disclose a great similarity in the tools, weapons, and ornaments of their inhabitants.

Projectile points (a term we use because "arrowhead" implies use of the bow and arrow) make up by far the most numerous type of artifact recovered; and these tend to be long and heavy, although proportions may be either narrow or broad. The size of these points indicates that instead of the bow and arrow the dart was used with the "atlatl," the Aztec name we have adopted for the throwing stick or spear thrower. This is confirmed by the presence of many antler hooks for the end of the throwing stick. Shaped much like the hook of a giant crochet needle, these engaged the notched butt of the dart shaft. Additional evidence is found in the special stone, antler, or shell weights which were attached to the shaft to add momentum to the throw.

Mullers and pot boilers were important kitchen tools.

Shell mound people of the Archaic period are the first whose axes

we can surely identify. The hafting groove encircled the ax completely

or, in the three-quarter-groove form, was omitted from the bottom edge.

Length, 22 inches.

Tools included grooved stone axes, chipped drills, and large chipped knife or scraper blades. Mullers, or flared-end "bell" pestles, were used to reduce wild plant foods to edible form; but the mortars or trays with which they were used are thought to have been made mostly of wood. Vessels of soapstone or sandstone were added to the skinlined pit or basket, and the flat pieces of steatite with a large hole bored in them may have been used with these containers for stone boiling. Fish were caught with bone fishhooks and with nets weighted with grooved or notched stones. Bone was also used for awls, which were probably employed in making baskets and for simple stitching operations as in the making of leather moccasins or leggings, as well as for projectile points and flaking tools. Bone heads served as ornaments, as did bone pins which were often decorated, though the plainer ones may have been used merely to secure clothing. Shell was worked into beads of many varieties, and into gorgets or pendants in addition to the atlatl weights mentioned.

Life on the shell mounds, or in the camps along streams and rivers where this source of food was of minor importance, was hardly different in most of its material aspects from that of the wandering hunters who had gone before. Permanent dwellings were still apparently unknown; and the rough shelters which were built were doubtless much the same crude lean-to of poles and brush or tree bark as formerly. Areas which appear to have been floored with clay and the remains of many hearths indicate that the shell mounds themselves were the actual habitation sites. This is confirmed by the presence of the numerous articles of daily living mixed in with the shells. The dead, too, were buried directly in the mound, most commonly in small round pits which required that the corpse be tightly flexed. Dogs were also buried in this manner occasionally, and we can guess either that they were loved by their masters or that they held some special religious significance. The fact that a very few shell mounds were intentionally formed into a large ring, as much as 300 feet in diameter, provides a definite hint of religious ceremonialism. From the few objects of daily use or adornment placed with the dead, we can assume they believed in an after life.

Except for caves, a rough windbreak to give protection from had weather

was probably the only shelter known to the earliest Indians.

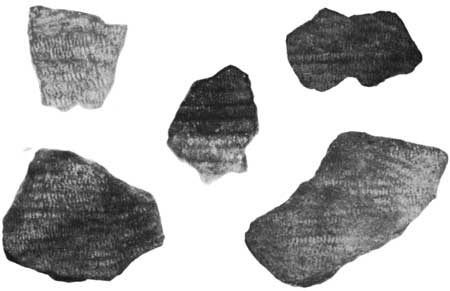

The life of these Indians continued unchanged in any of its major features until perhaps 2000 or 1500 B. C. About that time, according to radiocarbon dating, the knowledge of pottery making seems to have reached them in some manner which has not yet been determined. Perhaps they even discovered it for themselves; but it seems more probable that the idea reached them from some fairly distant tribe, and that by local experiment they developed their own techniques from a hazy understanding of the principles involved. At any rate, the upper levels of the older shell mounds begin to yield "sherds" (fragments) of a coarse undecorated pottery which contains innumerable tiny holes running through the paste in all directions. These are the channels which remain after some vegetable material like grass or moss fibers was burned out when the vessel was fired. Any substance mixed with the clay to make it easier to handle and keep it from cracking during the drying out and final firing of the pot is known as "temper," and the process itself is called "tempering." Later potters learned that a temper of sand, crushed shell, or, better still, crushed rock or crumbled bits of old pottery made stronger and better pottery; and therefore "fiber-tempered" wares usually represent the oldest type of pottery we find in any region where they occur. While this pottery was undecorated at first, its makers in the Georgia area later developed a type of decoration composed most often of lines of indentations, or punctates, made with the point of a stick or a bone tool.

Fiber-tempered pottery might be only a crude beginning of the

potter's art, but even these vessels were large and strong enough to be

highly useful. Width, 15 inches.

This new item in the household inventory was probably one of the most significant advances which ever took place in the life of the American Indian, and second in importance only to the later introduction of agriculture. With it, the awkward and tedious routine of stone boiling came to an end, and soups and stews enlarged the menu and became at once the easiest prepared and one of the most appetizing of the foods used. Pottery, too, marks a big change in the work of the archeologist when it appears in the cultures which he is studying. Types of projectile points and other stone artifacts have a way of continuing in use for long periods without change. Clay vessels, however, seem to have been constantly changing in form or decoration or construction, possibly because the potter's clay is so plastic and responsive to any fancy it is desired to express, and there are many different ways of producing similar results. For this reason, it forms a sensitive indicator of the passage of time and is one of our best clues to relationships between sites and the cultures of their inhabitants.

Simple stamping, as in this Mossy Oak jar, often appears like

crude scratching. Height, 10 inches.

No sizable shell mounds of these Archaic peoples, as they are known to the archeologist, have been found in the central-Georgia area. Numerous sites occur here, however, which contain no pottery but are littered with scraps of worked flint and where large numbers of the heavy Archaic projectile points are plowed up annually. At other sites, including those on the Macon Plateau, these points are found with a considerable quantity of the distinctive fiber-tempered pottery. It appears, therefore, that the Shellfish Eaters proper were a limited portion of the population of that era and that others with just about the same material equipment followed the old hunting and gathering life in temporary camps. The shell heaps themselves were occupied for rather brief periods by single groups of people. Possibly the large shell mounds represent an annual camping spot for numerous groups who used them successively and at other times of the year lived chiefly on game or along the smaller rivers where shell fish were available but not in such vast quantities. This would account for the smaller accumulations of shells in some areas; and it could be that recent changes in the courses of such rivers as the Ocmulgee and the Oconee, brought about by industrial activity and flood control measures, have resulted in the obliteration of small heaps of this sort.

In any case, it appears that the Macon Plateau had again demonstrated its advantages as a habitation site, and that a people with a material culture similar to that of the Shellfish Eaters dwelt here at intervals during the period 2000 B. C. to 100 B. C. Their residence was not continuous for very long at any one time, however, since their lives depended on hunting. Instead they probably moved about over a fairly large area, returning every so often to the familiar banks of the Ocmulgee to set up their village again and to hunt the surrounding region until the game once more became scarce.

The woven basketry fabric which produced these impressions is

among the earliest recorded in eastern North America

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Dec 2 2002 10:00:00 am PDT |