|

OCMULGEE National Monument |

|

Restored eagle effigy of white quartz boulders near Eatonton, Ga.

Length, 102 feet; width, 120 feet.

Potmaking Becomes an Art

The next period which can be clearly identified on the Macon Plateau is the one whose inhabitants we have called Early Farmers. It lasted for roughly 1,000 years and naturally witnessed considerable change; yet the evidence for this change in middle Georgia is tantalizingly slender. There are more and larger sites, and the increase of population reflected in these might be thought to signify an increased food supply such as the beginnings of planting and tending a few crops could produce. Direct evidence for the introduction of such hoe cultivation, however, is lacking; and we can only say that a number of different lines of reasoning lead us to believe that some plants—possibly pumpkins, beans, sunflowers, and tobacco—probably were being cultivated before the period ended. Through the provision of increased leisure and stability, an assured food supply may well have been one of the factors permitting an enrichment of Indian life at this time. Since this cannot yet be demonstrated, however, we must turn to what we do know. Perhaps the reader will not be too surprised to learn that we shall again be talking about pottery, since we have already mentioned it as one of the archeologist's most unfailing sources of information.

Like most archeological field work the excavations at Ocmulgee did not result in an independent body of information which could be added unchanged to the total fund of our archeological knowledge. We know in detail what was found; but we must turn to work in nearby and more distant areas for assistance in its correct interpretation. In the present case, four main types of pottery occurred more or less intermixed at almost the deepest levels excavated on the plateau. The first of these was the fiber-tempered ware described in the previous section. The other three are tempered with sand or with "grit" (finely crushed stone) in varying amounts. Like the fiber-tempered pottery these three types are important time markers in the Southeast. It would be tedious to go in detail through all the steps involved in placing them in their proper position in the time scale; but some idea of the nature of the problem might help us to gain an understanding of its complexities. It could help us, too, to realize what a jigsaw puzzle an archeological reconstruction is likely to be.

First let us see what we know about the earliest appearance of pottery in eastern North America. It has long been thought, and radiocarbon tests have recently demonstrated, that the earliest pottery known in this section has come chiefly from the area drained by the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers from New York State to Illinois and south as far as north Georgia. This pottery has such close parallels at a like early period in northeastern Asia that many students believe it may have been brought here by direct migration, though naturally over a period of generations. Its chief characteristic is the roughening of its surfaces with the marks of twisted cords and somewhat later with those made by a plaited basketry fabric. Here, some believe, must have been the models which stimulated the shellheap dwellers to their first experiments in making pottery.

Reconstructed pottery stamps. Designs taken from sherds excavated at the

Swift Creek site. Total length of paddle, 9 inches.

The two sand-tempered wares in the early Macon Plateau collections referred to above are Mossy Oak Simple Stamped and Dunlap Fabric Marked. The name of the first of these combines that of the site with which it was first principally identified with an indication of its general type, i. e., exhibiting the straight grooves left by the paddle used in finishing the pot. The paddle itself may have been carved with simple straight grooves, or it may have been wrapped with a thong or smooth bit of plant fiber such as honeysuckle vine. Dunlap, on the other hand, is the name of a family which had long owned a large part of the Ocmulgee area, while the type designation refers to the use of a piece of woven basketry used in finishing the vessel.

In order to place these two types of pottery we must examine their occurrence on the Georgia coast and in north Georgia. Such a study reveals that the simple stamping follows directly after fiber tempering on the coast; and that in north Georgia, where the latter is absent, it lies immediately above a fabric-marked pottery very similar to Dunlap. It would seem likely, then, that this latter type of pottery might have worked its way south by the end of the period in which fiber temper was in vogue. Both types exhibit a kind of finish which, like the early cordmarking farther north, resulted from techniques that had probably been found most effective in working the wet clay. Some sort of implement was needed for thinning and compacting the vessel walls, and experiment has shown that a paddle with roughened surface is more efficient for this purpose than a smooth one. No doubt this is caused by the more tenacious adherence of the wet clay to the latter. In any event, different ways were found of roughening a flattened stick or paddle, whether by wrapping various materials about it or carving it with deep grooves; and some groups may well have rolled up a piece from an old broken basket or bit of matting and found it equally useful. Then, if a smooth surface were desired, the marks of any of these implements could be erased easily by smoothing with a wet hand.

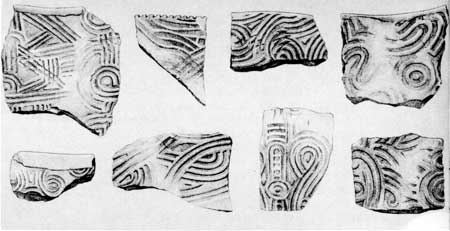

Fragments of Swift Creek stamp designs. Scale about

two-fifths.

The time we have been describing belongs to the general period of eastern United States archeology known as Early Woodland. The Adena culture, which apparently spread from centers in the Ohio Valley, belongs to this period and is well known for its elaborate burial mounds and other distinctive features which are regarded as typical markers over a wide area. While no burial mounds are known from middle Georgia at this time, the fabric-marked and simple-stamped pottery does belong to a general class of wares occurring also in Adena sites. It seems also to relate Ocmulgee to a pair of eagle effigy mounds of stone near Eatonton, Ga.; and bird symbolism is likewise a distinctive Adena feature, though one more fully developed in the following Middle Woodland stage. So it appears that a few traits have been found to connect this period quite definitely with some of the broader currents affecting other areas in the same time span.

The fourth pottery type found mixed in the lower levels at Ocmulgee was Swift Creek Complicated Stamped. Actually this was either grit- or sand-tempered; but its outstanding characteristic was the complex patterns with which the paddles were carved. The type is named for the Swift Creek site only a few miles down the river which was occupied almost exclusively by the people of this culture. This ware covers a longer time span than the other two types, and its distinctive influence was exhibited in some sections even into historic times. In its early stages, it probably served as the source for a tradition of complicated stamping which covered most of the Southeast and even spread to some extent beyond its limits. We don't know just when it began. In northwest Florida and on the Georgia coast it seems to fall in the Middle Woodland period. Since the type site, though, is close to its apparent center of development, its occurrence on the plateau mixed with Mossy Oak and Dunlap may well represent its true position and thus place its origins in Early Woodland.

Swift Creek villagers preferred these roughly

chipped axes to ones of ground stone. Many are too light for real

chopping and may have been weapons, kitchen tools, or even digging

implements. Length, 22 inches.

During its long history, a number of changes may be seen in the form and decoration of Swift Creek pottery. The commonest vessel shape consists of a deep jar with slightly flaring rim and nearly conical base. Many of the earlier pieces had four small bumps at the point of the base, as a sort of reminder of the feet which were common, also, on earlier pottery in nearby areas; these disappeared in the later examples. The lip of the jar, too, was only crudely finished in the earliest forms, being left rough and irregular or sometimes haphazardly notched or scalloped with pressure from the potter's finger. In time the edge tended to be pushed out a little; and this gradually developed into a smooth outward fold of the lip and finally a collar of smooth clay about an inch in width about the rim. This extreme "folded rim," however, occurs after the Master Farmer period shortly to be described.

Straight tubes of steatite or soapstone are the earliest known

form of pipe. They probably belonged only to shamans or medicine men.

These come from north Georgia. Lengths, 2 inches and 11 inches.

As for decoration, no description can adequately convey the wealth and variety of complex and often highly attractive designs with which Swift Creek pottery is stamped. The fragments illustrated give some idea of the general effect obtained, but only a painstaking reconstruction of the entire stamp can do them adequate justice. Intricate and beautifully proportioned combinations of curved and straight lines are numerous. Despite the cruder efforts which are naturally common, one is constantly surprised at the artistry exhibited in even the less expertly conceived decorative motifs.

As we should expect, this form of expression underwent such changes as might occur in the development of any form of art. The earliest paddles were carved with many narrow, shallow grooves in a pattern of two or more chief design elements. Smaller elements were used to connect these, fill in blank spaces, and generally round out the paddle. In time, however, the designs grow bolder and were more deeply cut as the motifs became better organized and as unnecessary filler elements could be eliminated. These, of course, are not the sort of differences to enable one to judge a particular sherd as early or late; but in very general terms, they describe the distinctions which become apparent when large numbers of sherds from different time periods are examined. It should also be pointed out that this remarkable pottery style covered such a wide area that any simplified description can only suggest a few general features which appear widely applicable, while recognizing that particular areas had their own varying histories of the type.

This temple mound is a lasting memorial to the energy of the Master

Farmers, the fourth group to occupy Ocmulgee.

Nothing has been said about other distinctive features of this period of development in Georgia. Projectile points vary from heavy, shapeless forms with stems to smaller triangular ones without. Flat stones with two holes through them were once presumed to have been used as gorgets, i. e., hung upon the chest as a sort of decoration, but they may well have been atlatl weights or served some other purpose. "Boatstones" and the prismatic form of atlatl weight are also said to occur, but there is some disagreement on this and even on the continued exclusive use of the atlatl in this period at all. In some areas the large numbers of smaller points may suggest that the bow and arrow were beginning to be used. The characteristic ax of the period was roughly chipped in a double-bitted form. Steatite or soapstone was still fashioned into crude bowls and the perforated net sinkers or pot boilers we have noted previously, as well as into short tubular pipes which are found in the region of central Georgia.

Just as Mossy Oak and Dunlap in Georgia appear to reflect more noteworthy developments farther north, so Swift Creek has its more spectacular parallels, too. These relate to Hopewell, the outstanding culture of the Middle Woodland period. The Hopewell burial mounds and other massive and complex earthen structures were accompanied by an overall artistic achievement in pottery, chipped and polished stone, bone, sheet mica, and copper which is probably with out equal among North American Indians. These materials were traded far and wide so that Hopewellian influence is strongly indicated in the neighboring states of Florida, Alabama, and Tennessee. Even Georgia shows some evidence of Hopewell connections, although in middle Georgia this is confined to the complicated stamped pottery. Types evidently related to Swift Creek occur frequently in classic Hopewell sites. In north Georgia, however, elaborately carved stone pipes are said to denote this relationship, and it is even more clearly indicated by a number of burial mounds. One of them, built of stones, contained a burial displaying such typical Hopewell features as a covering of mica plates and a breast plate and celt of copper.

During the Early Farmer period, then, we feel that the Indians in middle Georgia must have become more settled. Fragile pottery is not easily carried in any quantity by wandering bands of hunters. On the other hand, the technique of gathering wild foods is not likely to have become suddenly so efficient that this alone could account for the large increase in population which must be reflected in the more numerous sites. Knowledge of planting and plant care, too, is likely to have spread piecemeal rather than as a single unit. Hence, as we have already stated, this seems the most likely period for the Indians to have begun learning to raise some of the many plants which not too long afterwards became so important in their existence.

Early stage in excavation of the ceremonial earthlodge at

Ocmulgee.

In central Georgia, though, we see instead a different side of their lives. We follow the experiments made by the Indian women of the several tribes in trying to improve the pottery which had now become such an important utensil in their homes. Stronger vessels would break less easily; so paste was improved from time to time, if this end was not outweighed by other considerations. The attractiveness of the finished piece, however, was soon a matter of universal concern, at least to the potters themselves; and as their skill increased and their ideas and standards became more clearly defined, we can follow a process which never ceases to astonish us by its workings in our own society. The whims of fashion surprise and puzzle us today as they are expressed in our women's clothing, our automobiles, our houses, and our furnishings. Evidently, however, if we may judge by the variations in his wife's pottery, they were hardly less a problem to the Indian of 2,000 years ago.

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Dec 2 2002 10:00:00 am PDT |