|

OCMULGEE National Monument |

|

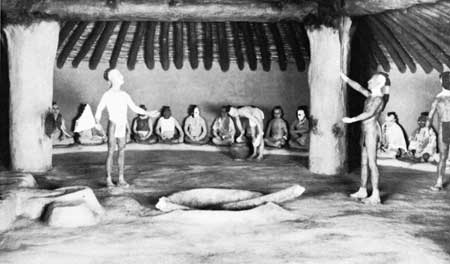

Council meeting in Master Farmer winter

temple. Museum diorama.

Temple Mounds and Agriculture

We now come to the period in Ocmulgee history which is the most plentifully supplied with facts resulting from the excavations. The Master Farmers, which is the name chosen for these people in the Museum exhibits, were newcomers to Ocmulgee. It may be that their arrival was strongly resisted by the Early Farmers who had claimed title to these lands for the past thousand years. About A. D. 900, they moved into this area, probably from a northwesterly direction, and started to build villages with some very novel features.

We do not know where this migration had its start; students of the subject believe that it may have begun in the Mississippi Valley near the mouth of the Missouri River. We do know, however, that some of their closest relatives settled in northeastern Tennessee; and perhaps, as the ancestral group journeyed up the Tennessee River it split apart at the point of that river's abrupt northward bend in northern Alabama. Then a succeeding generation, which took central Georgia for its home, settled in two places near the Ocmulgee River. The smaller village was about 5 miles below the present city of Macon on a limestone remnant known as Brown's Mount; the larger, with which we are here concerned, was the "Ocmulgee Old Fields" of the early settlers, across the river from the modern city and adjoining its eastern limit.

The most important feature distinguishing these people from their predecessors, however, was not their town but their very way of life. They were farmers; besides tobacco, pumpkins, and beans, they cultivated the New World staff of life, corn. This way of life enabled them to settle in one place long enough and in sufficient numbers to create a large village, and to develop the religious and ceremonial complex which was expressed in its numerous distinctive structures. They built it on the rolling high ground above the river, where their square, thatched houses were scattered among the many buildings connected with their form of worship. These latter consisted of rectangular wooden structures which we call temples, and a circular chamber with a wooden framework covered with clay which was a form of earth lodge. From our knowledge of the later Indian pattern in this area, we believe that these represented the summer and winter temples, respectively, of the tribe. Here the grown men took part in religious ceremonies and held their tribal councils; and here the chief could render decisions in individual disputes, or in matters of importance to the tribe as a whole.

The photo in the original handbook

pictured human remains. Out of respect to the descendants of the people

who lived at Ocmulgee, the depiction of human remains and

funerary objects will not be displayed in the online edition.

A log tomb and its central location may indicate

the principal burial in the first stage of the Funeral Mound. The

face-down position could result from the reassembled bones being wrapped

in a skin or mat for burial.

The photo in the original handbook

pictured human remains. Out of respect to the descendants of the people

who lived at Ocmulgee, the depiction of human remains and

funerary objects will not be displayed in the online edition.

Masses of shell beads must have been valued

possessions of many of the earlier temple mound

dignitaries.

Perhaps the single outstanding archeological feature to be disclosed by the excavations at Ocmulgee is the preserved floor and lower portions of one of these winter temples. The remains consist of a low section of clay wall outlining a circular area some 42 feet in diameter. At the foot of the wall, a low clay bench about 6 inches high encircles the room and is divided into 47 seats, separated by a low ramp of clay. Each seat has a shallow basin formed in its forward edge, and three such basins mark seats on the rear portion of a clay platform which interrupts the circuit of the bench opposite the long entrance passage.

This platform, on the west side of the lodge and extending from the wall almost to the sunken central fire pit, is the most remarkable feature of all. Slightly higher than the bench, it forms an eagle effigy strongly reminiscent of a number of such effigies embossed on copper plates which are a part of the paraphernalia of the Southern Cult religion, to be described in a later section. Surface modeling of the tapering body section may once have been present, but is now so much obliterated that only a sort of scalloped effect across the shoulders can be made out. Nevertheless this feature is present on at least two of the plates mentioned, one from the Etowah site in north Georgia and the other from central Illinois. Moreover both of these figures, which represent the spotted eagle, are distinguished by the same, almost square, shape of the body and wings with only a slight taper from their base toward the shoulder. Finally, the head of the platform eagle is almost entirely filled with a clear representation of the "forked eye," which is presented also, though in smaller scale, on the two figures in question, and is a distinctive symbol of the Southern Cult. The entire ceremonial chamber has been reconstructed on the basis of burned portions of the original which were uncovered by excavation. It forms one of the principal exhibits of the monument, and represents a unique archeological treasure.

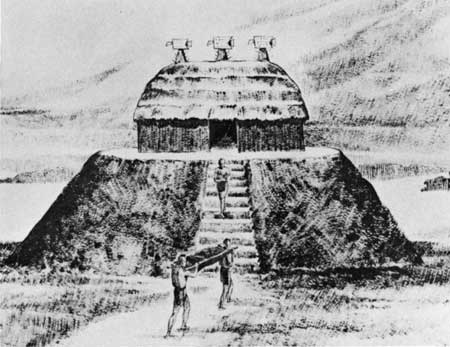

Fourteen clay steps, buried under later mound

construction, led up the west slope

of the earliest funeral mound to its summit.

Other structures uncovered included a small circular hut framed with poles and containing a large fireplace, out of all proportion to the size of the building. This was evidently a sweathouse where steam was produced by throwing water on heated stones; but it is not known whether this common form of purification was related to their religion or merely a sanitary feature of the village life. At the west edge of the village the tribal chiefs and religious leaders were buried in great log tombs where from one to seven bodies, possibly those of wives and retainers, were deposited with masses of shell beads and other ornaments befitting their rank. Over the whole was raised a low flat-topped mound with 14 clay steps leading to the summit.

Pottery for everyday use was plain but well made and came in a large

variety of pleasing shapes. Diameter of jar on right, 14 inches.

Beside their large and thriving religious center, we can reconstruct many aspects of their daily lives in which the Master Farmers were different from their predecessors. This difference is noted in their tools, weapons, and household utensils. These have survived because they were made of such durable material as stone and pottery. The many smaller projectile points now making their appearance suggest that the bow and arrow were in general use at this time. Greater range and accuracy have been advanced as possible reasons for adopting this weapon in place of the spear thrower and dart, which preceded the bow in most parts of the world. Perhaps equally important was an increase in tribal unrest and strife which made a larger quantity of relatively small and light missiles more effective in the brief skirmishes of Indian warfare than two or three of the bulkier darts. With regard to their other equipment, surprisingly few bone tools have been preserved; but this may be due to their greater use of cane, which was very effective for knives, awls, and other implements but did not last as well as bone. Evidence has also been found to show that they manufactured and used basketry and a simple twined weave type of cloth fabric.

The pottery obtained in excavation has already been studied in considerable detail because of the recognized importance of this time marker to the archeologist. It is here that we find one of the most noticeable differences between these people from the Mississippi Valley and the native Georgia tribes whose pottery had developed along very different lines for some thousand years or more. Now) in place of the many forms of surface roughening which marked the history of the latter, plain surfaces become the rule. Jar forms have rounded bottoms, are often as broad as they are tall, or broader, and show a tendency toward constricted openings. One common form has a straight sloping shoulder which turns in from the rounded body contour of the pot rather suddenly. Its slope may continue without change to the rim, but more often it will turn upward again to form a slight lip or even a short neck. These contrast with the deep jars of the preceding period in which the mouth, regardless of neck or rim treatment, tends almost to equal the largest diameter, and in which the base is conoidal, i. e., rounded to at least the suggestion of a point.

The clay figures which often adorned the rims of

open bowls represented all manner of creatures both real and imaginary.

About one-third actual size.

Of course the Master Farmers made other types of pottery, too. Some were open bowls, and others had an incurving rim which gracefully repeated the curve of the lower portion just below the belly. There were also deep, straight-sided jars with extremely thick walls, and big shallow bowls several feet in diameter which have been called salt pans from the belief that the type was sometimes used in the making of that substance. Actually they were probably the large family food bowl in common use also in later times. Impressions of a twined cloth fabric on the outer surfaces of the latter, some cord marking, and crude scoring or other treatment of the sides of the former were exceptions to the general rule of smooth surfaces during this period.

Effigy bottles were usually a finer grade of

pottery and generally accompanied burials. The hole in the human figure

is in the hack of the head; the face is painted while, the body red, and

the hair the natural brown of clay. Diameter of bottle, 5-5/16

inches.

In place of surface decoration, however, we find another form of elaboration which is somewhat less common but equally distinctive. This is the attempt to depict some form, either natural or supernatural, in the body of the vessel or attached to it in some way as an independent figure. Small heads suggesting a fox or an owl or some night creature with big staring eyes grow out of the rim of a bowl and peer into it. The small handles which are fairly common on the straight-shouldered jars often have two little earlike knobs at the top; and knobs and bosses with more or less modeling of the body of the pot are frequently used to represent gourds or squashes or some other vegetable which is not easy to identify. One curious style of jar has a neck which is closed at the top, something like a gourd, but has an opening about an inch in diameter below this on the side. Modeling at the top suggests ears, a style of hair arrangement, or some other human or animal feature that gives rise to the name, "blank-faced effigy bottle."

In time, other changes began to mark the village of the Master Farmers. The temples, built originally at ground level, were rebuilt occasionally; and with the leveling of the old building to make way for the new the surrounding ground surface was raised at first into a small platform. Gradually this platform was increased in height and size until the mound at the south side of the village was some 300 feet broad at the base and almost 50 feet high. The other temple mounds grew in a similar fashion but were either started later or were less important and so never achieved as great a size. The earthlodges, too, were sometimes rebuilt and often on the same site; but no attempt was made to increase their elevation. The funeral mound, however, followed the pattern of the others; and in each new layer of the seven there were fresh burials of the village leaders, and on top of each a new wooden structure which may have been connected with the preparation of the dead for their final rites. In the later stages, too, the flat summit area was surrounded by an enclosure of wooden posts.

The structure atop the funeral mound may have been

for preparing corpses for burial. From Museum

exhibit.

At the northwest corner of the village lay a cultivated field which surrounded the site of one of the earlier temples. This was no ordinary field since most of these must have lain in the bottom land below the village. From its position, then, could we infer some sacred purpose, possibly to create an offering to the spirits, or by the power in its seed absorbed from the surroundings to increase the yield of the villagers' crops? In any case, the mounds for succeeding structures were gradually raised above it; and by this act the rows were buried and thus preserved as conclusive proof of the advanced state of culture which the Master Farmers had achieved.

This series of cultivated rows buried beneath the

fill of later mound construction confirms our belief that the temple

mound builders lived mainly by farming.

The construction of all these mounds and earthlodges required a large amount of material as well as innumerable man-hours of labor. Two series of great linked pits, averaging about 7 feet deep and 18 by 40 feet in area, seem to indicate that the earth was obtained immediately outside the main village limits, for they have been traced around considerable portions of its north and south borders. They do not enclose the entire area occupied by the temple mounds, though, because at least three of these mounds lie outside their confines today; others were destroyed in the construction of Fort Hawkins and the adjacent portions of East Macon a little farther to the north. It is not unlikely that the irregular ditches formed by these pits served also as a protection against raids on the village; for otherwise, why would their course have outlined the village area so closely?

All the evidence, then, points to the existence here at Ocmulgee of a town of Indians who lived in a state of culture as advanced in some respects as any to be found north of Mexico. We see a prosperous community devoted chiefly to the yearly round of activities designed to cement its relationship with the powerful unseen forces on which its well-being depended. Not too much work was required with the abundant rainfall on this fertile soil to raise the principal food supply for an entire family. The men, like all later Indians, hunted to supply the meat for their diet; but they had plenty of free time to devote to the construction and repair of the town's several temple buildings. Here they gathered at stated intervals to go through the time-honored ritual first taught to their fathers by the very spirits themselves, those spirits which gave man the fish and the game and finally the wonderful gift of the corn plant. All of these gifts and many more must be accepted with reverence and treated according to the rules established for their proper use; otherwise the spirits would be offended, the game would disappear, and the fields would wither and die.

General view of excavations northeast of

ceremonial earthlodge, showing portion of trench surrounding the

village.

Of all the annual round of ceremonies the most important was that in honor of the deity whose gift of corn had the miraculous power to renew itself every year. The summer temple, then, was the scene of the year's biggest festival when the new crop was ripe. All the fires of the village were put out; and after the men had fasted and purified themselves with the sacred drink, the new fire was lit and offered with the first of the new corn to the Master of Breath. With this act the sins of the past year were forgiven, and the town entered upon a new year with rejoicing. But ever so often the temple needed to be rebuilt, perhaps at the death of the chief priest, who may at the same time have been the chief of the town as well. This called for a mound to be built or the old one to be enlarged and raised higher as a mark of extra devotion; and every man must have given his allotment of working days to complete the project, even if several years were required before it was finished. For the new mound was proof to the divine forces of how much their gifts had been appreciated, and a plea that their favor might continue and the town prosper. Also it was proof to all the surrounding tribes of the wealth and strength of the village which was able to erect and maintain these large structures and at the same time to live in plenty and defend itself from its enemies.

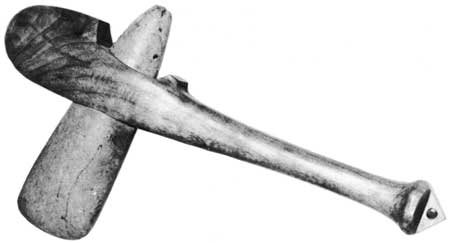

Ungrooved ax, or celt, of the temple mound

builders

Much of this reconstruction depends heavily on our knowledge of the later tribes of the Southeast and on broader analogies as well. Archeological proof does not exist for much that we have inferred. Yet we know that what we find here could not have been built by villagers living at the level of bare subsistence. Economic surplus was essential, and we know the Indians had the corn with which to create it. Strong leadership was needed to carry such large projects to completion; and with it there must have been a social and religious class system to organize the economic and priestly functions of such a community. The temple priests and their assistants and retainers would have formed a rather numerous class with high status in a society so clearly impressed with the importance of the physical expression of its religious ideas. Wealth and power may likewise have rested with a specialized warrior class which controlled the governing function of the group, or it may be that these were combined with the religious duties of the priestly class. Whatever the system employed, several hundred unusually important individuals given special burial in the Funeral Mound attest to the distinctions which existed. Class differences of this sort are the most common basis for a high degree of social and political control; and Ocmulgee is a good example of the real attainments of some American Indians along these lines.

In spite of the relatively large amount of information we have about them, however, we know surprisingly little of the ultimate fate of the Master Farmers. We do know that these first bearers of an alien culture from the Mississippi Valley did not persist very long in the area in terms of its previous history. Within 200 years the busy village was deserted, only to be visited by an occasional traveling band descended from the Early Farmers who had lived on in nearby sections. We do not know even whether the last occupants left here in a body to settle elsewhere, whether they gradually died off, whether they were absorbed into the surrounding population, or whether they were finally exterminated by neighbors who had themselves developed large settled communities capable of effective military action. Other ideas came to Georgia from the Mississippi Valley, but Ocmulgee lay silent and was passed by. Only in the last chapter of Indian history in this State was the site again reoccupied for a brief time. Here at the end, to be described in our final chapter, we find the Creek Indians once more living among the haunts of their ancestors.

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Dec 2 2002 10:00:00 am PDT |