|

OCMULGEE National Monument |

|

Model of portion of Lamar village, showing ball

post in plaza at foot of smaller mound.

Early Creeks

After the mound village at Ocmulgee was abandoned we lose the thread of Indian history in this area for about 250 years. When we pick it up again in the Reconquest period, it is at a new village some 3 miles down the river. Much had happened in the meantime, though; and we are able to piece together a good bit of the story.

In the first place, it is clear that the Master Farmers had been only a small group which had settled in this one small section of Georgia; and that the Early Farmers did not leave Georgia when they gave up their settlements along the Ocmulgee. We cannot say for certain either that they even quit the valley entirely. Their distinctive pottery seems to have continued the course of development already outlined, but during the interval a variety of new influences came in from other regions to produce a number of striking changes. Noteworthy among these were the "carinated" bowl form and incised and pinched or punctate decoration around the shoulder or rim. In its extreme form the first of these may be described as a shallow bowl with flaring sides which abruptly turn inward to form a distinct shoulder and inward-sloping rim. The angle thus produced may be as sharp as 90°, and the shoulder itself may vary from abrupt to more or less gently rounded. It is this flattened rim which normally bears the broad, deep incised-line decoration in the form of scrolls alternating with nested flat-topped pyramids or with inverted chevrons, all worked into a continuous pattern similar to the Greek fret. Below the shoulder, the body of the bowl still carries the old complicated stamping, but gradually the pattern be comes less distinct and the paddle is applied several times to the same spot. It is even impossible sometimes to make out any design whatever in the overall roughening.

Pottery bowl showing carinated shoulder, bold

incising, complicated stamping, and reed punctates typical of Lamar Bold

Incised. Diameter, 16 inches.

Another new element is to be found in a series of notches, bosses, or circular impressions which are applied just below the lip on jars or bowls with only complicated stamping, or at the point of the shoulder on "bold incised" vessels. The lip of most vessel shapes, except the carinated bowl, is thickened by folding or with an added strip of clay, and it is the lower edge of this band which is often pinched or otherwise worked to produce a notched or beaded effect. On the carinated bowls there is commonly a line of circular impressions made with the end of a piece of cane or other hollow tube situated on the point or bend of the shoulder to separate the area of incised decoration from the body stamping below. Circles of this sort are sometimes used in place of the beading around the rim.

Lamar Complicated Stamped jar.

Clearly defined stamping more common in early Lamar period.

Height, 9-1/4 inches

Whether the incised decoration and the carinated bowl form came from the Florida or the Mississippi Valley area has not yet been settled. Temple mounds, however, are a definite Mississippian trait; and the Lamar village below Macon, which has given its name to the archeological period we are discussing, is typical in possessing two mounds with an adjacent open court. The larger mound is rectangular, while the smaller is circular; but the latter is most unusual in its spiral ramp which leads counterclockwise to the top in four complete traverses about the mound. Mounds showing this feature have been reported by early travelers, but this is the only one known to exist today.

Lamar mound with spiral ramp, after initial

clearing.

The village occupied a low natural ridge of higher ground in the swamp close to the river. This position may have been chosen for its inconspicuous and defensible nature, or to be close to good farmland; but we do know that it was surrounded by a palisade of upright logs some 3,500 feet in length to protect it from enemy attacks. Within the enclosed area, the rectangular houses were grouped about the mounds and the nearby court. Their construction consisted of a framework of light posts interlaced with cane which was plastered with clay and roofed with sod or some sort of grass thatch. Some of them were raised on low dirt platforms, evidently as a protection from the periodic overflow of the river.

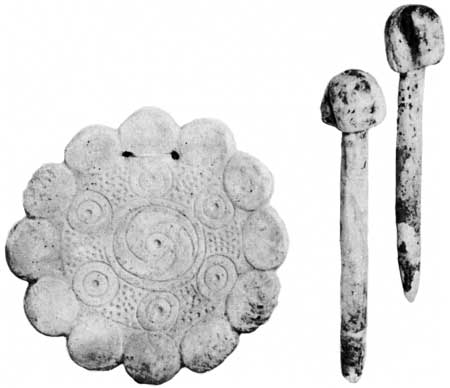

The life of these late prehistoric farmers was otherwise much the same as that of their predecessors who had lived on the bluffs up the river. To be sure, the region was now more thickly settled, and other villages like theirs could be reached by a short journey in almost any direction. Farming was doubtless the principal activity; and burned corncobs and beans have been found, indicating two of the important crops. Hunting, likewise, continued as a major pursuit; and the small, triangular projectile points tell us that the bow was now the favorite weapon even though large, stemmed dart or spear points were still made. Small, flat celts of triangular outline were used. Shell was extensively worked for ornament, mainly in the form of large beads, large, knobbed pins which seem to have dangled from the ears, and circular gorgets bearing designs of the Southern Cult, to be discussed presently.

Pipes in both plain and fancy styles were numerous.

Gorgets were made of the outer shell, and large beads and these knobbed

"ear bobs" from the inner whorl of the marine whelk, or conch. "Ear

bobs" about 5 inches long.

Finally, smoking appears to have become so habitual that it may have been released from the religious implications which everywhere seem to accompany the use of tobacco in aboriginal America. Pipes in an astonishing variety of skillfully executed shapes, principally of clay but also in stone, have been found scattered throughout the village refuse. Human heads with great goggle eyes, bird and animal heads, boats (?), and a stylized representation of a hafted celt are common.

DeSoto probably encountered some distant towns of these people when he explored Georgia in 1540, and they were undoubtedly the ancestors of various historic Creek Indian tribes of this State. We have suggested that their culture was a mixture of very old elements in the region, such as complicated stamping, with newer ideas coming in with the Master Farmers or even later, such as temple mounds and incised decoration. We know from work in other areas that the Early Farmer bearers of the Swift Creek tradition had continued their existence uninterrupted save only in the immediate vicinity of Macon. Therefore, despite the admixture of many outside influences, we see in the reappearance here of one of their major cultural elements, the old paddled pottery surfaces, proof that the basic culture and presumably the people themselves were still the same. In effect, an actual reoccupation of the area seems indicated; and it is this fact that the museum exhibits recognize in the name 'Reconquest" given to the period we are discussing.

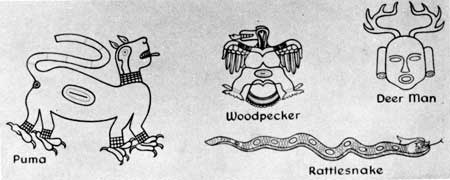

Some of the important beings of the Southern Cult as depicted on

shell or copper.

The culture represented at the Lamar site just described, which is the type site for this archeological period, covered a very wide geographical range and lasted in some locales into the historic period. Typical Lamar pottery is found on numerous sites in regions as widely separated as Florida, Alabama, the Carolinas, and even parts of Tennessee. We know that it was made by the historic Cherokee, which accounts for the persistence of complicated stamping into historic times mentioned earlier, and possibly also by some Siouan-speaking tribes in the Carolinas, as well as by the early Creeks. While not all elements of the culture were uniformly shared in all of these areas, there can be little doubt that the material aspects of the lives of these different groups were surprisingly much alike. This may appear the more remarkable when one considers the difference in language and even the active hostility of such historic tribes as the Creek and the Cherokee. Nevertheless, one has only to consider the diversity of modern European nations sharing a single culture which we know as "Western Civilization" to realize that language, nationality, and culture are not mutually interrelated on any one-to-one basis.

Mention has been made of the Southern Cult. Briefly, this is the name given to the religious idea behind a group of frequently recurring symbols, and the paraphernalia on which they are depicted, which have been found all the way from Oklahoma and the Great Lakes to Florida and the gulf coast. These unusual articles occur in association with the platform mounds, and at some sites appear to be limited to the graves of an important class of personages who had the unique privilege of burial within the sacred structures atop the mounds.

The objects themselves appear to be symbols of office or religious vessels or regalia of diverse sorts. They include engraved circular gorgets of shell, engraved copper plaques, hafted ceremonial axes made of copper or from a single piece of stone, as well as stone axheads either so finely made or of such soft material that they could not have been put to practical use. A ceremonial atlatl looks to us more like a mace or sceptre; both this form and that of the hafted ax are reproduced in beautifully chipped flint, and these are found in association with long blades and reproductions of other elements of the cult in the same material. Vessels include conch shell cups and pottery bottles of various forms.

Museum exhibit portraying eagle-costumed figure embossed on copper

plate from the Etowah site, north Georgia. Original about 20 inches high.

Of perhaps even greater importance than the physical apparatus just described are the symbols pictured on some of these specimens, and representations of these and other objects being worn or carried by god-animal beings, mythological creatures, or their impersonators. Important figures of the mythology or the religious pantheon include the eagle, ivory-billed woodpecker, and turkey; various forms of the rattlesnake, the cat or mountain lion; and the human chunkee player. These are depicted most clearly on some of the engraved copper plaques like that of the Eagle Man from the Etowah site, which is reproduced in the Ocmulgee Museum in the colors most likely to have been used in the original costume. They are also engraved on shell cups, masks, and gorgets and on pottery vessels. Among the important symbols occurring alone or as ornament on these figures are the cross, swastika, sun circle, hi-lobed arrow, forked eye, hand and eye, and death head. The figures are also shown brandishing the ceremonial atlatl, holding a long flint knife, or throwing the chunkee stone; and some wear the hi-lobed arrow as a hair ornament. The forked eye, sun circle, and other symbols are shown painted on these figures or on their regalia.

We are still uncertain as to the origin and significance of the Southern Cult, although we know that it is associated with the platform or temple mounds of the late Mississippian period, and that it very likely represents the ritual which accompanied the use of these mounds. One interesting suggestion has been made as to the motives behind its development, relating these rather closely to the effects of the introduction of corn agriculture. Populations naturally increased rapidly with the improved food supply. Good land thus becoming relatively scarce, tribes were no longer able to find suitable areas for new settlements, as our Master Farmers had done, by the simple act of moving to another region. At the same time the success of their crops grew steadily more vital to the life of the tribe, and this, in turn, led to a great elaboration in the worship of the special dieties connected with them, i.e., the Southern Cult. This theory seems logical as far as it goes; but the forces which are seen at work are not of a sort likely to reverse direction. Therefore other factors would have to be introduced to account for the later decline of this religious phenomenon.

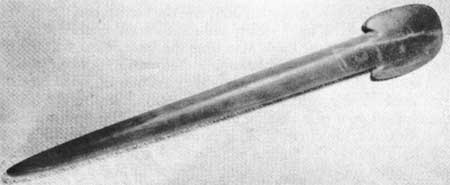

Ceremonial ax from burial near Funeral Mound. Length, 19 inches.

Various explanations have been advanced to account for the actual origin of the Southern Cult, where it first appears, and from what source or sources its several elements were drawn to enrich the ceremonial life of the temple mound builders. Suggestions of Middle American origins have thus far failed to receive any but the vaguest support from the existing evidence. Agreement appears to be general, on the other hand, that many of the basic elements from which it could have been formed are contained in Hopewell. The emphasis on large marine shells and on copper is shared by both; and acquisition from Hopewell of the method for supplying these scarce or remotely situated materials might well have encouraged an interest in expanding and beautifying the ceremonial apparatus. The artistic skills of the older culture, too, might possibly have passed into the hands of a new school of artists who sought to express with them the religious ideas or mythology of their own people. The techniques of the two art styles are basically similar, and the Southern Cult closely approaches both the technical proficiency and the facility of expression which are so characteristic of Hopewell. The connection appears to stop there, however; for aside from one or two isolated designs occurring on Florida Hopewellian pottery, nothing has been found from which the Southern Cult designs could reasonably be thought to have developed.

The earliest expressions of the Southern Cult to appear in the Macon area occur in the Master Farmer period. The eagle effigy platform of the ceremonial earthlodge seems to portray the spotted eagle of the Southern Cult and, in any case, a distinct representation of the forked eye, probably the earliest use of this symbol on record. A ceremonial ax from the vicinity of the Funeral Mound is also typical, while the more Hopewellian traits such as undecorated shell cups and gorgets and cut animal jaws (unique, however, in their copper plating) may be thought to argue for origins from this direction. It was during the interval while Ocmulgee was abandoned that this religious idea must have reached its fullest and most elaborate expression; and this period probably corresponds to that of the occupation of the Etowah site in north Georgia, where much of the spectacular material was found. By the time the Lamar village was occupied, however, the vigor of this form of religious expression seems to have been already on the wane. Engraved shell gorgets occur, but only in the simpler designs; perhaps the hafted ax form of pipe could be considered a Southern Cult object or at least to show its influence. Possibly more complete excavation would reveal additional and more distinctive paraphernalia.

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Dec 2 2002 10:00:00 am PDT |