|

CHICKAMAUGA and CHATTANOOGA National Military Park |

|

Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant. Courtesy National Archives. |

Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman. Courtesy National Archives. |

Reinforcements for the Besieged Army

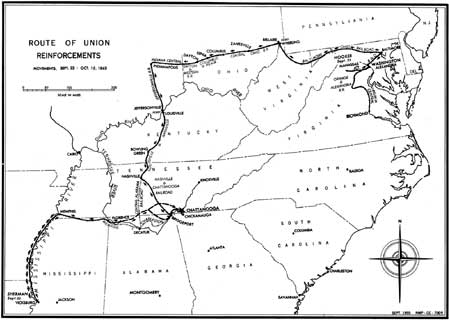

As early as September 13, General in Chief Halleck ordered reinforcements sent to Rosecrans. His dispatches on September 13, 14, and 15 to Major Generals Hurlbut at Memphis and Grant and Sherman at Vicksburg directed the troop movements. These dispatches, however, were delayed for several days en route from Cairo to Memphis and, in the meantime, the Battle of Chickamauga was fought. Grant received the orders on the 22nd and immediately instructed four divisions under Sherman to march to Chattanooga.

One division of the Seventeenth Corps, already in transit from Vicksburg to Helena, Ark., was ordered to proceed on to Memphis. General Sherman quickly brought three divisions of his Fifteenth Army Corps from the vicinity of the Big Black River into Vicksburg, where they embarked as fast as water transportation could be provided. By October 3, all of the movement of 17,000 men was under way.

The route of travel was by boat to Memphis, then by railroad and overland marches to Chattanooga. From Memphis the troops followed closely the Memphis and Charleston Railroad, which Sherman was ordered to repair as he advanced. By November 15, the troops were at Bridgeport, Ala., having traveled a distance of 675 miles.

When the War Department in Washington received word that the Army of the Cumberland was besieged in Chattanooga, it considered the situation so critical that President Lincoln was called out of bed late at night to attend a council meeting. This meeting occurred on the night of September 23, and is described by Nicolay and Hay:

Immediately on receipt of Rosecrans dispatch, Mr. Stanton sent one of the President's secretaries who was standing by to the Soldier's Home, where the President was sleeping. A little startled by the unwonted summons,—for this was "the first time" he said, Stanton had ever sent for him,—the President mounted his horse and rode in through the moonlight to the War Department to preside over an improvised council to consider the subject of reinforcing Rosecrans.

There were present General Halleck, Stanton, Seward and Chase of the Cabinet; P. H. Watson and James A. Hardie of the War Department, and General D. C. McCallum, Superintendent of Military Transportation. After a brief debate, it was resolved to detach the Eleventh and Twelfth Corps from the Army of the Potomac, General Hooker to be placed in command of both . . .

(click on map for an enlargement in a new window)

The movement of the Eleventh and Twelfth Army Corps from the Army of the Potomac to Tennessee eclipsed all other such troop movements by rail up to that time. It represented a high degree of cooperation between the railroads and the government and was a singular triumph of skill and planning. It also shows the great importance the War Department attached to the Chattanooga campaign.

The troops began to entrain at Manassas Junction and Bealton Station, Va., on September 25, and 5 days later on September 30 the first trains arrived at Bridgeport, Ala. The route traveled was by way of Washington, D. C.; Baltimore, Md.; Bellaire and Columbus, Ohio; Indianapolis, Ind.; Louisville, Ky.; Nashville, Tenn.; and Bridgeport, Ala. Several major railroad lines, including the Baltimore and Ohio, Central Ohio, Louisville and Nashville, and Nashville and Chattanooga were involved.

Not all of the troops, however, made such good time as the first trains, and for the majority of the infantry the trip consumed about 9 days. The movement of the artillery, horses, mules, baggage, and impediments was somewhat slower, but by the middle of October, all were in the vicinity of Bridgeport ready to help break the siege.

These two corps under Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, comprising 20,000 troops and more than 3,000 horses and mules, traveled 1,157 miles. Differences in the railroad gauges hampered the movement, but most of the changes in gauge occurred at river crossings which had no bridges and the troops had to detrain at these points anyway.

Confederate cavalry raids, bent on destroying the railroad bridges and otherwise interfering with the reinforcing effort, imposed a more serious difficulty, but, except for delaying the latter part of the movement a few days, the raids were ineffective.

At the beginning of the siege, the Union Army had large supply trains in good condition and transporting supplies seemed feasible. But early in October rain began to fall and the roads became almost impassable. To make the situation more critical Bragg sent Wheeler to harass and destroy the Union supply trains as they moved over Walden's Ridge on their trips to and from Bridgeport. Wheeler destroyed hundreds of wagons and animals and it was not long before the Union soldier received less and less food. Wagon horses and mules and artillery horses were on a starvation diet and many died each day.

Chattanooga headquarters of General Rosecrans during the siege.

Courtesy National Archives.

Command of the two hostile armies had undergone a considerable change during the siege period. Grant received orders to meet "an officer of the War Department" at Louisville, Ky. He proceeded by rail to Indianapolis, Ind., and just as his train left the depot there, en route to Louisville, it was stopped. A message informed Grant that Secretary of War Stanton was coming into the station and wished to see him. This was the "officer" from the War Department who gave Grant command of the newly organized Military Division of the Mississippi. Thomas replaced Rosecrans. McCook and Crittenden had previously been relieved of their commands and their corps consolidated into the Fourth Corps under command of Granger. Stanton accompanied Grant to Louisville and there the two spent a day reviewing the situation.

In Bragg's camp, Polk was relieved of his command, and Lt. Gen. William J. Hardee rejoined the army. Bragg's army was reorganized into three corps commanded by Longstreet, Hardee, and Breckinridge.

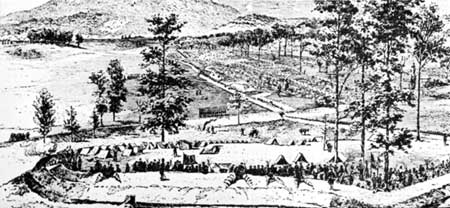

Entrenchments of Thomas' Corps, Army of the Cumberland in front of

Chattanooga. Lookout Mountain in distance.

From Battles and Leaders of the Civil War.

When Grant reached Chattanooga on October 23 he found a plan already drawn up to open a new supply line for the besieged army. This plan of necessity was conditioned upon the terrain and the configuration of the river between Bridgeport, the railhead and base of supplies for the Union Army, and Chattanooga. (After the Tennessee River passes the city it flows southward for some 2 miles until it strikes Lookout Mountain where, after a short westerly course, it curves northward. This elongated loop of the river is called Moccasin Bend.)

The plan called for 1,500 men on pontoons to float down the river from Chattanooga during the night of October 26-27 while another force marched across Moccasin Point to support the landings of the river-borne troops. Grant ordered the plan executed. The pontoon borne troops quickly disembarked upon striking the west bank at Brown's Ferry, drove off the Confederate pickers, and threw up breast works. The troops marching across the neck of land came up to the east side of the ferry, joined this group, and constructed a pontoon bridge.

Hooker's advance from Bridgeport coincided with this action. He marched by the road along Raccoon Mountain into Lookout Valley. There he met the advance post of a Confederate brigade and drove it back. Maj. Gen. O. O. Howard's Eleventh Corps moved to within 2 miles of Brown's Ferry, while Brig. Gen. John W. Geary of the Twelfth Corps remained at Wauhatchie to guard the road to Kelley's Ferry.

The Confederates made a night attack against Geary which the latter repulsed, but both sides lost heavily. After this action, the short line of communication with Bridgeport by way of Brown's and Kelley's Ferries was held by Hooker without further trouble.

With the successful seizure of Brown's Ferry and construction of a pontoon bridge across the Tennessee River there, and Hooker's equally successful advance from Bridgeport and seizure of the south side of the river at Raccoon Mountain and in Lookout Valley, the way was finally clear for the Union Army to reopen a short line of supply and communication between Chattanooga and Bridgeport, the rail end of its supply line. This "Cracker Line" ran by boat up the Tennessee River from Bridgeport to Kelley's Ferry. Above Kelley's Ferry, the swift current made the stream unnavigable at certain points to boats then available. Accordingly, at Kelley's Ferry, the "Cracker Line" left the river and crossed Raccoon Mountain by road to Brown's Ferry. There it crossed the river on the pontoon bridge, thence across Moccasin Point, and finally across the river once more into Chattanooga.

Early in November, Bragg ordered Longstreet to march against Burnside in East Tennessee with Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaw's and Maj. Gen. John B. Hood's Divisions of infantry, Col. E. Porter Alexander's and Maj. A. Leyden's battalions of artillery, and five brigades of cavalry under Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler—about 15,000 men in all. This movement caused great anxiety in Washington and the authorities urged Grant to act promptly to assist Burnside. Grant felt that the quickest way to aid him was to attack Bragg and force the latter to recall Longstreet. On November 7, Thomas received Grant's order to attack Bragg's right. Thomas replied that he was unable to move a single piece of artillery because of the poor condition of the horses and mules. They were not strong enough to pull artillery pieces. In these circumstances, Grant could only answer Washington dispatches, urge Sherman forward, and encourage Burnside to hold on.

|

|

|

Last Modified: Fri, May 17 2002 10:00:00 pm PDT |