|

SCOTTS BLUFF National Monument |

|

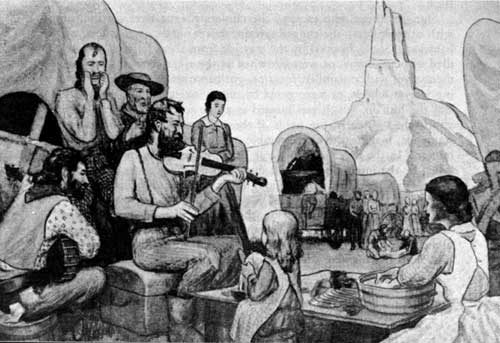

Cavalcade of the Forty-niners.

Original sketch in Oregon Trail Museum.

Scotts Bluff and the Forty-niners

Early in the spring the Forty-niners converged by steamboat upon the Missouri River towns of Independence, Westport, and St. Joseph; assembled wagons, animals, and provisions; and organized into companies. Eager to reach the new Eldorado, they were undismayed by the prospective 2,000-mile trek across hostile plains and mountains. On May 1, as soon as the prairie grass was green, the great gold rush began. The Oregon Trail became the California Road.

The trail from Independence, up the Kansas and Blue Rivers, joined the trail from St. Joseph near present Marysville, Kans., then followed up the Little Blue to its source to reach the "Coast of Nebraska," historic Platte River. Just beyond was Fort Kearny, established in 1847, now commanded by the same Captain Bonneville who first took wagons across the Continental Divide 17 years before.

Onward from Fort Kearny the white-hooded prairie schooners crawled like an army of gigantic ants along the south bank of the Platte. The Forty-niners were awed by the vast emptiness of the treeless plains, the endless horizon, the shimmering haze, and the sudden, drenching thunderstorms. Pushing beyond the forks of the Platte, they followed the margin of the South Platte to near the present town of Ogallala, Nebr. Here, at what was called Lower California Crossing, they ferried or swam the river amid scenes of shouting confusion, then headed for the North Platte.

Hundreds of extant emigrant journals vividly describe the classic trunk route of the Oregon-California Trail up the North Platte. From the plateau the trail descended rather abruptly via steep Windlass Hill down Ash Hollow (near Lewellyn) to the river. Hugging the south bank, the trail passed many curious hills and formations which afforded welcome relief from the monotonous scenery. Courthouse and Jail Rocks near present Bridgeport, Chimney Rock near Bayard, and Scotts Bluff were among the most notable of these landmarks, which so frequently aroused poetic fancies and rapturous descriptions in emigrant journals.

At Scotts Bluff in 1849 the trail made a wide detour, south of the present monument, up Gering Valley, and over Robidoux Pass, then northwest to regain the Platte near the mouth of Horse Creek.

Sixty miles beyond the bluff the Forty-niners came to historic adobe-walled Fort Laramie (Fort John of the American Fur Company), which was in the very process of being purchased by the United States Army. The Stars and Stripes were hauled up at the fort on June 26, and the army immediately began the construction of new buildings. Pausing here only briefly to rest and obtain provisions, the emigrants continued west and north via the North Platte and the Sweetwater toward the Continental Divide, guided by such landmarks as Laramie Peak, Red Butte, Independence Rock, Devil's Grate, and Split Rock. Just beyond broad, barren South Pass, flanked by the snow-covered Wind River Mountains, the Forty-niners reached the edge of the Pacific drainage. They still had a grueling journey over mountain and desert before they would reach the end of their rainbow.

The California gold rush of 1849 and ensuing years, in addition to being on a much larger scale, was entirely different in character from the earlier Oregon migration. Oregon travelers were families, seeking farms; most of the California emigrants were young men, unmarried or unaccompanied by wives, who were seeking a quick fortune. Young women who did make the hazardous journey were besieged with suitors. There were weddings and honeymoons on the trail. There are also records of gold rush babies born in wagon beds.

After a rugged day on the trail, the evening campfire was often the occasion for yarn-swapping and sentimental songs, like Oh, Susanna! It can be imagined that these campfire scenes were commonplace at Scotts Bluff and the tale of Hiram Scott's tragic death was doubtless repeated with endless variations. The prevailing mood was not always gray. The haunting mystery of Scotts Bluff struck a fittingly somber note for the Forty-niners. Before the epic drama of the gold-rush was played out a few years later, 20,000 of these adventurous emigrants had died and lined the California Road with their graves.

Asiatic cholera was the greatest killer. Ships docking at New Orleans brought infected people who carried the dread disease by steamboat up the Mississippi to St. Louis. There, the disease spread by contagion to people in the Missouri River outfitting towns. As the tired Argonauts struggled across the unfamiliar Nebraska landscape, the disease raced like wildfire among them, decimating their number.

Children were orphaned. The husband who buried his wife might himself be dead the next day. Numerous diaries record inscriptions on the crude headboards of the hastily dug shallow graves. Hundreds of burials took place in the North Platte Valley between Ash Hollow and Fort Laramie. Several have been identified at Scotts Bluff.

Many of those who escaped the cholera plague were confronted with other killers—the rugged terrain, inexperience, carelessness, exhaustion. Some dropped by the wayside from sheer fatigue. Others died of pneumonia, or were drowned at the river crossings, or shot themselves with unfamiliar firearms, got run over by the big lumbering wagon wheels, or were gored by unruly oxen. Another menace was the buffalo, which was hunted as a fine source of food. Unless approached gingerly, big herds of these creatures would sometimes stampede, making the earth tremble, trampling to death the unwary hunter. In the desert of the Great Basin, more of the travelers were killed by the intense heat, alkali dust, and parching thirst. The trek of the Forty-niners was not for long a gay escapade; it became a grim survival of the fittest.

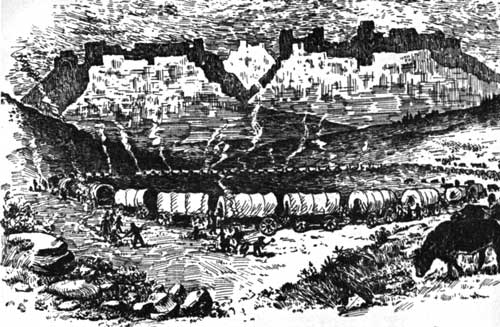

"Camp at Scott's Bluffs." From The Old

Journey

Contemporary sketch by Alfred Lambourne.

Contrary to popular impression, the number of emigrants who died at the hands of marauding Indians was negligible. The Diggers along the Humboldt River in Nevada accounted for some stragglers; the Plains Indians were a bit thievish but peaceful—for a time, at least. True, at nights the wagons were arranged in a circular compound and guards were posted; but an Indian attack on the emigrants Hollywood style, was a rarity.

Although visions of an Indian raid served as a healthy influence on emigrant vigilance, daily preoccupation with the necessities of life was a more pressing concern. There were three primary needs—food, grazing, and good campsites. Although some of the better organized companies had ample provisions, many others miscalculated and suffered accordingly. True, buffalo, antelope, and other game were hunted; but the wildlife was frightened by the endless, noisy, dusty column, and the hunters who galloped forth with romantic notions of a dashing buffalo hunt often came back empty-handed.

The ideal campsite would boast a good spring and a generous supply of timber for campfires and the repair of wagon gear. There were a few such campsites—Scotts Bluff with its springs and its ponderosa pine and cedars was one of the best—but these soon suffered from the pressure of converging crowds. Clear springs were muddied, the sparse groves of timber were chopped away, and the grass vanished from overgrazing or withered in the summer sun.

The emigrant guidebooks—Hastings, Fremont, Joseph Ware, and others—were usually adequate as a rough index to the whereabouts of obvious landmarks and choice campsites, but they were deficient in sound advice to the tenderfoot. It wasn't always possible to reach a good campsite, and then one had to camp out on the prairie, conserving the precious water supply and eating a cold supper. Smart emigrants learned the old trappers' practice of gathering bois du vache (dried buffalo dung) to make an acrid but usable campfire.

In camp at Chimney Rock

Original sketch in Oregon Trail Museum.

A typical wagon train with all its encumbrances, plus quicksand, mud, creek crossings, and other difficulties of terrain, could make but 15 to 20 miles per day over the level plains. In rough mountain country, progress was even slower; and there had to be frequent halts to rest worn-out, emaciated stock and to mend faulty gear. Thus it took perhaps 4 months for a train to reach a California gold camp. (Starting on May 15, the crest of the migration wave would pass Scotts Bluff about mid June.) Some were later still, and had to be rescued from early snows of the Sierras. A disconsolate few would spend the winter at Fort Laramie or Salt Lake City.

Wherever and whenever they arrived, the Forty-niners were in scarecrow condition with few worldly possessions. Stoves, anvils, plows, furniture, and hardware of every description were thrown overboard from prairie schooners to ease the strain on the animals. Often this sacrifice was in vain; dead horses and oxen, littered the road to California gold.

How many Forty-niners? The population of California increased some 40,000 in 1849; it is estimated that 15,000 sailed around Cape Horn or made sailing connections at Panama; of 30,000 who went overland, perhaps 5,000 died en route. In seven succeeding years, 1850-56, the California gold rush was resumed each spring. No official census was possible, but a register kept at Fort Laramie helps to estimate that during the period 150,000 people journeyed overland westward. The peak year was 1852, when an estimated 50,000 emigrants poured through Scotts Bluff Pass.

|

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Dec 9 2000 10:00:00 am PDT |