|

SCOTTS BLUFF National Monument |

|

Mitchell Pass looking west.

Courtesy of Downey's Midwest Studio, Scottsbluff, Nebr.

Oregon-California Trail Geography at Scotts Bluff

Today the hills of the North Platte Valley are not accounted among the scenic wonders of the United States; in Oregon Trail days, to emigrants who had been bored with the flatness and drabness of the Platte scenery, and who would be too exhausted later to appreciate the grandeur of the Rocky Mountains, the landmarks along the Platte had a captivating charm. Courthouse Rock and Chimney Rock were the appetizers; Scotts Bluff was the grand climax.

A typical journal entry of 1849 is that of Alonzo Delano:

June 9: The wind blew cold and unpleasant as we left our pretty encampment this morning for Scott's Bluff, a few miles beyond. The bare hills and water-worn rocks on our left began to assume many fantastic shapes, and after raising a gentle elevation, a most extraordinary sight presented itself to our view. A basin-shaped valley, bounded by high rocky hills, lay before us, perhaps twelve miles in length, by six or eight broad. The perpendicular sides of the mountains presented the appearance of castles, forts, towers, verandas, and chimneys, with a blending of Asiatic and European architecture, and it required an effort to believe that we were not in the vicinity of some ancient and deserted town. It seemed as if the wand of a magician had passed over a city, and like that in the Arabian Nights, had converted all living things to stone.

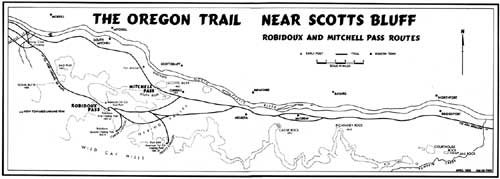

Recent research has cleared up long-standing confusion about the geography of the Oregon-California Trail in the vicinity of Scotts Bluff. Today Scotts Bluff is understood to mean the large bluff within the national monument, between the river badlands and Mitchell Pass, which separates it from a ridge extending westward at a right angle; about 10 miles south of the river, parallel to this ridge, lies the Wildcat Hills, which extend for over 25 miles, from Chimney Rock to Robidoux Pass (see map). Because of this modern nomenclature, some historians have misunderstood the emigrant diaries, failing to realize that in Oregon Trail days Scotts Bluff, frequently spelled "Scott's Bluffs," commonly referred to all these hills, including the Wildcat Hills. William Kelly, above-mentioned, showed remarkable acumen in likening the outline of Scotts Bluff to a shepherd's crook, with the present Wildcat Hills as the straight staff and present Scotts Bluff as the flair at the end of the crook.

Similarly, the identity of the pass at Scotts Bluff has frequently been misunderstood. In historic times there were actually two different passes here. The first, which would be at the bow of the shepherd's crook, is now called Robidoux Pass, and this was predominantly used during the period up to and including 1849. In October 1850, Government explorer Capt. Howard Stansbury, returning from Salt Lake, reported the first evidence of wagon wheels through the gap now called Mitchell Pass.

Explanation for the splitting of the Oregon-California Trail at Scotts Bluff lies in its peculiar topography. The main bluff lays like a giant whale across the valley floor, blocking the way, with impenetrable badlands between it and the river. Although the existence of Mitchell Pass was, of course, known prior to 1850, it was little used because of its rugged badlands character. Travel via Robidoux Pass involved a wide swing away from the river, beginning at a point west of present Melbeta and proceeding down present Gering Valley, south of Dome Rock. In T. H. Jefferson's Map of the Emigrant Road, it is called Karante Valley.

Emigrant John Brown in 1849 noted that "14 miles from Chimney Rock the road [to Robidoux Pass] leaves the river. . . . [It] lies through one of the finest valleys I ever saw and is decidedly the best twenty miles of road we have travelled." Maj. Osborne Cross, leading a company of mounted riflemen to Fort Laramie, described the ascent to Robidoux Pass as "the first high hill since leaving Fort Leavenworth. This is partly covered with cedar, which was the first we had met on the march."

(click on image for larger size)

It is suspected that the U. S. Army Quartermaster from Fort Laramie was the first to take wagons through Mitchell Pass, possibly doing a little engineering to widen the passage and ease the grade. Later emigrants, finding wagon tracks now going toward Mitchell Pass, readily switched to the new route. The two branches came together once more east of Horse Creek.

During the summer migration of 1850, equal in volume to that of 1849, the Robidoux Pass route up Gering Valley was still favored. Bennett Clark refers to his "encampment within a semicircle of high bluffs, which rise abruptly from the river's edge and sweep around rain-bow like." To Franklin Street this camp at Scotts Bluff was "one of the most delightful places that nature ever formed." To Thomas Woodward, "Every place seems like a fairy vision. It is no use trying to describe [Scotts Bluff] for language cannot do it." To Mormon emigrant Leander V. Loomis the view of the bluffs from the north side of the river was "highly beautiful, almost approaching the sublime." His journal contains this delectable entry of May 30:

This morning there arose a heavy clowd between us and Scotts Bluff, which hid it entirely from view, and as it rolled away Showing first its lofty peak, which ascended Some 300 feet in the air, and which was covered with Small Pine or cedar trees, the scene was highly Novel, and no less beautiful we could see as it were, standing upon a clowd, a huge rock, covered with small trees, and as the clowd would rise and fall, it presented mutch the appearance of a Theater, the trees presented the appearance of the actors, the Rock, of the Stage—the clowd of the curtain, and nature itself was the tragedy they were Acting, each one playing there parts to perfection.

In 1851 use between the two passes was perhaps equally divided. William C. Lobenstine writes:

. . . We approached the Scotch Bluffs [sic], which we saw the evening before golden in the light of the setting sun, and our whole attention was attracted by the grandeur of the former, still more beautiful country. The appearance of these sand hills, although from far off like solid rock, has a very accurate resemblance to a fortification or stronghold of the feudal barons of the middle age, of which many a reminder is yet to be met with along the bank of the Rhine. The rock itself is separated nearly at its middle, having a pass here about fifty to sixty feet wide, ascending at both sides perpendicular to a height of three to four hundred feet. The passage through here was only made possible in 1851 and is now preferred by nearly all the emigrants, cutting off a piece of eight miles from the old road. We passed through without any difficulty and after having passed another blacksmith shop and trading post, which are very numerous, protection being secured to them by the military down at Fort Laramie, we encamped for the night.

With the migration of 1852, the historical spotlight permanently shifted to Mitchell Pass. During the early fifties the California migration reached its peak; the charms of Scotts Bluff and the peculiarities of the new pass were not lost on the new crop of journalists.

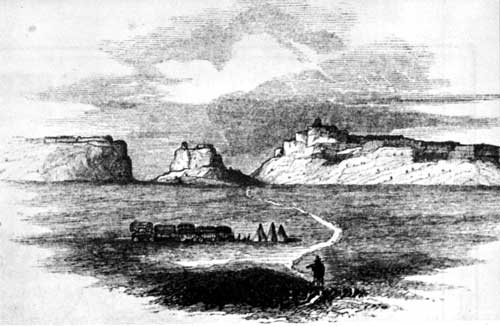

"Scott's Bluffs.".

From Richard Burton's City of the Saints, 1860.

It was in 1852, apparently, that the little-used name "Capitol Hills" was first applied to Scotts Bluff by Hosea Horn and other guidebook writers. The origin of this name is suggested in the Sexton diary of June 10:

Made our noon halt opposite Scott's Bluff, altogether the most symmetrical in form and the most stupendous in size of any we have seen. One of them is close in its resemblance to the dome of the Capitol in Washington.

There is a pass through that is guarded on one side by Sugar Loaf Rock, on the other by one that resembles a square house with an observatory. It is certainly the most magnificent thing I ever saw.

In the National Wagon Road, a guidebook by W. Wadsworth based on a trip of 1852, Scotts Bluff is one of the three major landmarks described on the whole California Road: "Here is some of the most beautiful and picturesque scenery upon the whole route." Wadsworth labels the Scotts Bluff of today as "Convent Rock." In 1853 Frederick Piercy made a remarkable sketch of the bluffs, with buffalo hunters in the foreground. He referred to these bluffs as "certainly the most remarkable sight I have seen since I left England."

The Celinda Himes diary of 1853, describing abandoned log structures, indicates the occasional use of Robidoux Pass in later years. The Helen Carpenter journal of 1856, freely quoted in Paden Wake of the Prairie Schooner, clearly describes the fork in the road east of Scotts Bluff but indicates that most people now took "the river road" through Mitchell Pass. She vividly describes also the sheer walls of Mitchell Pass, the excellent view to be had from the "summit" of the pass, the many inscriptions in the clay (long since vanished), and a soldier's grave on the side of the bluff.

To summarize, Robidoux Pass, 8 miles west of monument headquarters, was used by the Forty-niners and most of those who preceded them, including the fur traders, the emigrants to Oregon, Francis Parkman, Kearny's Dragoons, and the regiment of mounted riflemen under Maj. Winslow F. Sanderson who in 1849 rode to take over Fort Laramie. Robidoux Pass has historical primacy as "the first Scott's Bluffs Pass." On the other hand, "the second Scott's Bluffs Pass," now known as Mitchell Pass, was used by 150,000 or more emigrants, soldiers, and freighters of the 1850's and 1860's. And it was also the scene of the overland stage, the Pony Express, and the first transcontinental telegraph. Honors are about equally divided.

|

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Dec 9 2000 10:00:00 am PDT |