|

ANTIETAM National Military Site |

|

Focal point of the early morning attacks, the Dunkard Church and

some who defended it.

From photograph attributed to James

Gardner.

Courtesy, Library of Congress.

IN WESTERN MARYLAND is a stream called Antietam Creek. Nearby is the quiet town of Sharpsburg. The scene is pastoral, with rolling hills and farmlands and patches of woods. Stone monuments and bronze tablets dot the landscape. They seem strangely out of place. Only some extraordinary event can explain their presence.

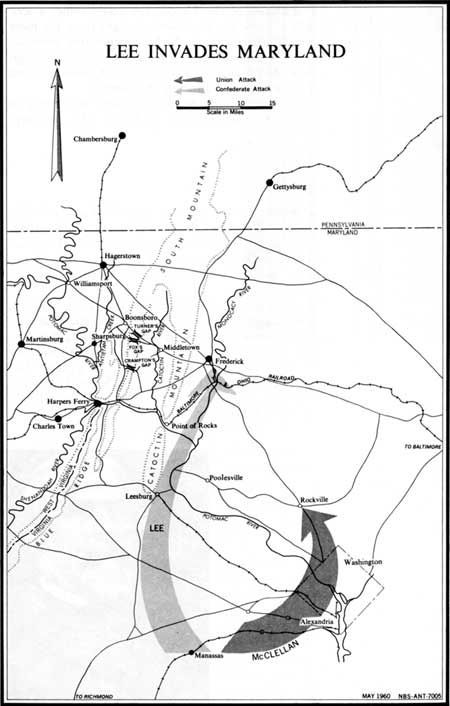

Almost by chance, two great armies collided here. Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia was invading the North. Maj. Gen. George R. McClellan's Army of the Potomac was out to stop him. On September 17, 1862—the bloodiest day of the Civil War—the two armies fought the Battle of Antietam to decide the issue.

Their violent conflict shattered the quiet of Maryland's countryside. When the hot September sun finally set upon the devastated battlefield, 23,000 Americans had fallen—nearly eight times more than fell on Tarawa's beaches in World War II. This single fact, with the heroism and suffering it implies, gives the monuments and markers their meaning. No longer do they presume upon the land. Rather, their mute inadequacy can only hint of the great event that happened here—and of its even greater consequences.

Across the Potomac

On September 5-6, 1862, a ragged host of nearly 55,000 men in butternut and gray splashed across the Potomac River at White's Ford near Leesburg, Va. This was Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia embarked on the Confederacy's first invasion of the North. Though thousands of Lee's men were shoeless, though they lacked ammunition and supplies, though they were fatigued from the marching and fighting just before the historic crossing into Maryland, they felt invincible.

Only a week before, August 28-30, they had routed the Federals at the Battle of Second Manassas, driving them headlong into the defenses of Washington. With this event, the strategic initiative so long held by Union forces in the East had shifted to the Confederacy. But Lee recognized that Union power was almost limitless. It must be kept off balance—prevented from reorganizing for another drive on Richmond, the Confederate capital. Only a sharp offensive thrust by Southern arms would do this.

Because his army lacked the strength to assault Washington, General Lee had decided on September 3 to invade Maryland. North of the Potomac his army would be a constant threat to Washington. This would keep Federal forces out of Virginia, allowing that ravaged land to recuperate from the campaigning that had stripped it. It would give Maryland's people, many of whom sympathized with the South, a chance to throw off the Northern yoke.

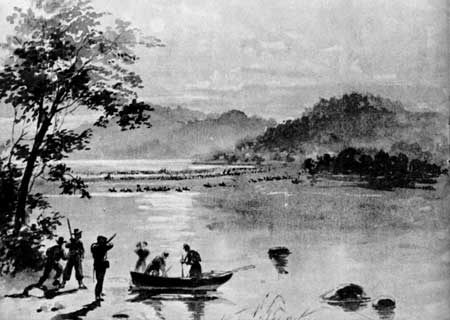

Lee's army crossing the Potomac; Union scouts in

foreground.

From wartime sketch by A. R. Wood.

Courtesy,

Library of Congress.

From Maryland, Lee could march into Pennsylvania, disrupting the east-west rail communications of the North, carrying the brunt of war into that rich land, drawing on its wealth to refit his army.

Larger political possibilities loomed, too. The North was war weary. If, in the heartland of the Union, Lee could inflict a serious defeat on Northern arms, the Confederacy might hope for more than military dividends—the result might be a negotiated peace on the basis of Southern independence. Too, a successful campaign might induce England and France to recognize the Confederacy and to intervene for the purpose of mediating the conflict.

So it was that the hopes of the South rode with this Army of Northern Virginia as it marched into Frederick, Md., on September 7.

(click on map for an enlargement in a new window)

|

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Mar 4 2002 10:00:00 pm PDT |