|

ANTIETAM National Military Site |

|

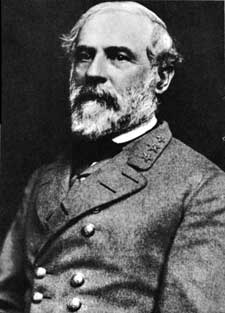

Gen. Robert E. Lee. From photograph by Julian Vannerson. Courtesy, Library of Congress. |

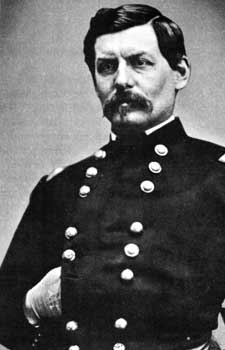

Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan. From photograph by Matthew B. Brady or assistant. Courtesy, National Archives. |

McClellan in Command

On that same September 7, another army assembled at Rockville, Md., just northwest of Washington. Soon to be nearly 90,000 strong, this was Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan's Army of the Potomac. Its goal: To stay between Lee's army and Washington, to seek out the Confederate force, and, as President Abraham Lincoln hoped, to destroy it.

Hastily thrown together to meet the challenge of Lee's invasion this Union army was a conglomerate of all the forces in the Washington vicinity. Some of its men were fresh from the recruiting depots—they lacked training and were deficient in arms. Others had just returned from the Peninsular Campaign where Lee's army had driven them from the gates of Richmond in the Seven Days' Battles, June 26-July 2. Still others were the remnants of the force so decisively beaten at Second Manassas.

In McClellan the Union army had a commander who was skilled at organization. This was the reason President Lincoln and Commander in Chief of the Army Henry Halleck had chosen him for command on September 3. In 4 days he had pulled together this new army and had gotten it on the march. It was a remarkable achievement.

But in other respects, McClellan was the object of doubt. He was cautious. He seemed to lack that capacity for full and violent commitment essential to victory. Against Lee, whose blood roused at the sound of the guns, McClellan's methodical nature had once before proved wanting—during the Seven Days' Battles. At least so thought President Lincoln.

But this time McClellan had started well. Could he now catch Lee's army and destroy it, bringing the end of the war in sight? Or, failing that, could he at least gain a favorable decision? A victory in the field would give the President a chance to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, which he had been holding since mid-summer. The proclamation would declare free the slaves in the Confederate States. By this means, Lincoln hoped to infuse the Northern cause with regenerative moral power. Spirits were lagging in the North. Unless a moral purpose could be added to the North's primary war aim of restoring the Union, Lincoln questioned whether the will to fight could be maintained in the face of growing casualty lists.

And so, followed by mingled doubt and hope, McClellan started in pursuit of the Confederate army. McClellan himself was aware of these mingled feelings. He knew that Lincoln and Halleck had come to him as a last resort in a time of emergency. He knew they doubted his energy and ability as a combat commander. Even his orders were unclear, for they did not explicitly give him authority to pursue the enemy beyond the defenses of Washington.

Burdened with knowledge of this lack of faith, wary of taking risks because of his ambiguous orders, McClellan marched toward his encounter with the victorious and confident Lee.

|

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Mar 4 2002 10:00:00 pm PDT |