|

ANTIETAM National Military Site |

|

First Virginia Cavalry at a halt during invasion of Maryland.

From wartime sketch by Waud. Courtesy, Library of Congress.

Lee Divides His Forces

Maryland was a disappointment to Lee. On September 8, he had issued a dignified proclamation inviting the men of that State to join his command and help restore Maryland to her rightful place among the Southern States. His words concluded with assurance that the Marylanders could make their choice with no fear of intimidation from the victorious Confederate army in their midst.

Maryland took him at his word. Her people did not flock to the Confederate standard, nor were they much help in provisioning his army. No doubt Lee's barefooted soldiers were a portent to these people, who had previously seen only well-fed, well-equipped Federal troops.

Deprived of expected aid, Lee had to move onward to Pennsylvania quickly. For one thing, unless he could get shoes for his men, his army might melt away. Straggling was already a serious problem, for Maryland's hard roads tortured bare feet toughened only to the dirt lanes of Virginia.

By now, Lee's scouts were bringing reports of the great Federal army slowly pushing out from Rockville toward Frederick.

Lee's proposed route into Pennsylvania was dictated by geography. West of Frederick—beyond South Mountain—is the Cumberland Valley. This is the northern half of the Great Valley that sweeps northeastward through Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania. That part of the Great Valley immediately south of the Potomac is called the Shenandoah Valley.

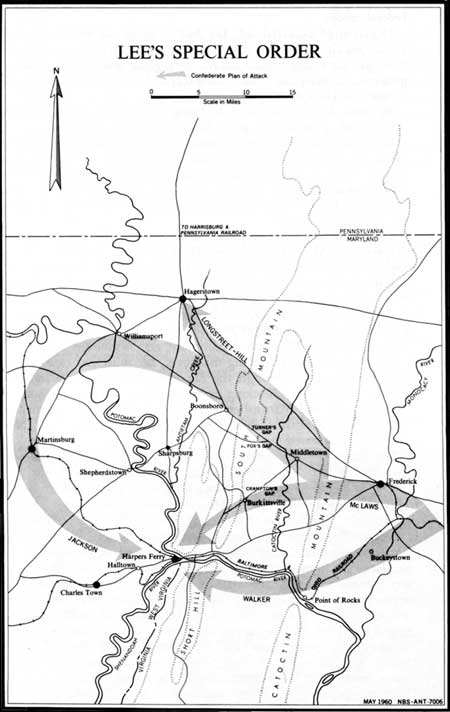

Lee planned to concentrate his army west of the mountains near Hagerstown, Md. There he would be in direct line with his supply base at Winchester in the Shenandoah Valley. After replenishing his supplies and ammunition, he could strike northeast through the Cumberland Valley toward Harrisburg, Pa., where he could destroy the Pennsylvania Railroad bridge across the Susquehanna River. Once loose in the middle of Pennsylvania he could live off the country and threaten Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington.

Before launching this daring maneuver, Lee must first clear his line of communications through the Shenandoah Valley to Winchester and to Richmond. Blocking it were strong Federal garrisons at Harpers Ferry and Martinsburg. Unaccountably, they had remained at their posts after the Confederate army crossed the Potomac. Now they must be cleared out.

Lee decided to accomplish this mission by boldly dividing his army into four parts. On September 9, he issued Special Order 191. Briefly, it directed Maj. Gen. James Longstreet and Maj. Gen. D. H. Hill to proceed across South Mountain toward Boonsboro and Hagerstown. Three columns cooperating under Maj. Gen. Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson were ordered to converge on Harpers Ferry from the northwest, northeast, and east. En route, the column under Jackson's immediate command was to swing westward and catch any Federals remaining at Martinsburg. Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws, approaching from the northeast, was to occupy Maryland Heights, which overlooks Harpers Ferry from the north side of the Potomac. Brig. Gen. John Walker, approaching from the east, was to occupy Loudoun Heights, across the Shenandoah River from Harpers Ferry. Maj. Gen. J. E. B. Stuart's cavalry was to screen these movements from McClellan by remaining east of South Mountain.

(At this point a fateful event occurred—one which was destined to change the subsequent course of the campaign. D. H. Hill, Jackson's brother-in-law, had until this time been under Jackson's command. Unaware that a copy of Lee's order had already been sent to Hill, Jackson now prepared an extra copy for that officer. Hill kept the copy from Jackson; the other was to provide the script for much of the drama that followed.)

Lee was courting danger by thus dividing his force in the face of McClellan's advancing army. Against a driving opponent, Lee probably would not have done it. But he felt certain that McClellan's caution would give Jackson the margin of time needed to capture Harpers Ferry and reunite with Longstreet before the Federal army could come within striking distance. That margin was calculated at 3 or 4 days. By September 12, Jackson's force should be marching north toward Hagerstown. As soon as the army reconcentrated there Lee could begin his dash up the Cumberland Valley into Pennsylvania.

So confident was Lee of the marching capacities of the Harpers Ferry columns, and so certain was he that McClellan would approach slowly, that he made no provision for guarding the gaps through South Mountain.

(click on map for an enlargement in a new window)

|

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Mar 4 2002 10:00:00 pm PDT |