|

ANTIETAM National Military Site |

|

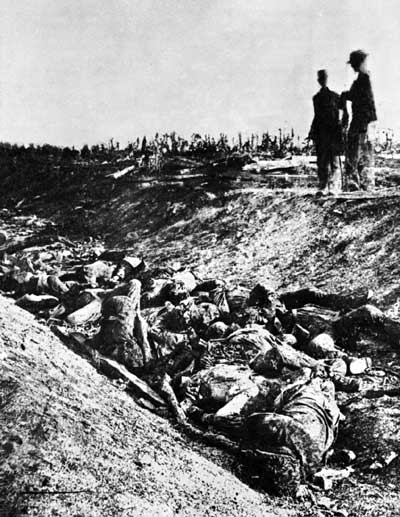

Sunken Road in 1877 (top).

The same view today (bottom).

The Fight for the Sunken Road

Sedgwick may have wondered, in the moments before the Confederate onslaught in the West Woods, why General French was not closely following him. Nor is it clear, in view of French's instructions, why he did not do so.

French's troops had crossed Pry's Mill Ford in Sedgwick's wake. After marching about a mile west, they had veered south toward the Roulette farmhouse, possibly drawn that way by the fire of enemy skirmishers. Continuing to advance, they became engaged with Confederate infantry at the farmhouse and in a ravine which inclines southward to a ridge. On the crest of this ridge, a strong enemy force waited in a deeply cut lane—the Sunken Road.

Worn down by farm use and the wash of heavy rains, this natural trench joins the Hagerstown Pike 500 yards south of the Dunkard Church. From this point the road runs east about 1,000 yards, then turns south toward the Boonsboro Pike. That first 1,000 yards was soon to be known as Bloody Lane.

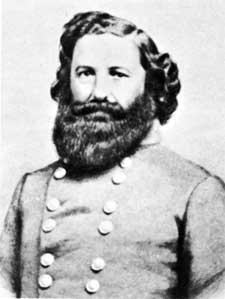

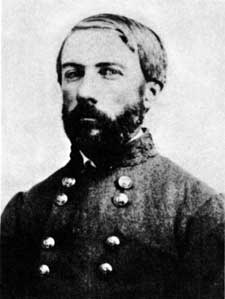

Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws, who led Maj. Gen. D. H. Hill. Courtesy, Library of Congress. |

Jackson's counterattack after the ambush. Courtesy, Frederick Hill Meserve Collection. |

Posted in the road embankment were the five brigades of D. H. Hill. At dawn these men had faced east, their line crossing the Sunken Road. But under the pressure of the Federal attacks on the Confederate left, they had swung northward. Three of Hill's brigades had been drawn into the fight around the Dunkard Church. Then Greene's Federals had driven them back toward the Sunken Road. There Hill rallied his troops. About 10:30 a.m., as the men were piling fence rails on the embankment to strengthen the position, a strong enemy force appeared on their front, steadily advancing with parade-like precision. It was French's division, heading up the ravine toward Sunken Road Ridge.

Crouched at the road embankment, Hill's men delivered a galling fire into French's ranks. The Federals fell back, then charged again. One Union officer later wrote: "For three hours and thirty minutes the battle raged incessantly, without either party giving way."

But French's division alone could not maintain its hold on the ridge. Hurt by fire from Confederates in the road and on either side, the Union men gave way. Still it was not over. French's reserve brigade now rushed up, restoring order in the disorganized ranks; once again the division moved forward.

Now, opportunely, Maj. Gen. Israel Richardson's Federal division—also of Sumner's corps—arrived on the left of French and was about to strike Hill's right flank in the road embankment.

It was a critical moment for the Confederates. Aware that loss of the Sunken Road might bring disaster, Lee ordered forward his last reserve—the five brigades of Maj. Gen. R. H. Anderson's division. At the same time Brig. Gen. Robert Rodes of Hill's division launched a furious attack to hold the Federals back until Anderson's men could arrive. This thrust kept French's men from aiding Richardson, who even now prepared to assault the Confederates in the road.

As French's attack halted, Richardson swept forward in magnificent array. Richardson was a tough old fighter—bluff and courageous, a leader of men. One of his officers recalled his leading the advance, sword in hand: "Where's General _________?" he cried. Some soldiers answered, "Behind the haystack!" "G-- d--- the field officers!" the old man roared, pushing on with his men toward the Sunken Road. In three units they passed to the east of the Roulette farmhouse and charged the Confederates at the crest of the ridge.

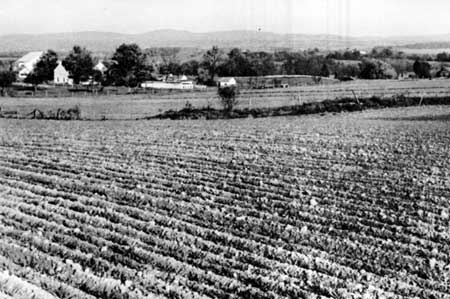

Mumma farm, left; Roulette farmhouse, far right. This view looking

east from Hagerstown Pike. French's division advanced from left toward

the Sunken Road, which is off picture to the right. Both farmhouses seen

in this modern view were here at time of the battle.

As the struggle increased in fury, R. H. Anderson's brigades arrived in the rear of Hill's troops in the road. But Anderson fell wounded soon after his arrival, and suddenly the charging Confederate counteroffensive lost its punch. By a mistaken order, Rodes' men in the Sunken Road near the Roulette lane withdrew to the rear. A dangerous gap opened on the Confederate front. The artillerist Lt. Col. E. P. Alexander wrote later, "When Rodes' brigade left the sunken road . . . Lee's army was ruined, and the end of the Confederacy was in sight."

Union Col. Francis Barlow saw the gap in the Confederate front opened by Rodes' withdrawal. Quickly swinging two regiments astride the road, he raked its length with perfectly timed volleys. Routed by this devastating enfilade, the Confederate defenders fled the road and retreated south toward Sharpsburg. Only a heroic rally by D. H. Hill's men prevented a breakthrough into the town.

The Sunken Road was now Bloody Lane. Dead Confederates lay so thick there, wrote one Federal soldier, that as far down the road as he could see, a man could have walked upon them without once touching ground.

The Federals had suffered heavily, too. Their bodies covered the approaches to the ridge. In the final moments, while leading his men in pursuit, Colonel Barlow had been seriously wounded; and shortly after, his commander, General Richardson, had fallen with a mortal wound.

The fight for the Sunken Road had exhausted both sides. At 1 p.m. they halted, and panting men grabbed their canteens to swish the dust and powder from their rasping throats.

The Confederate retreat from Bloody Lane had uncovered a great gap in the center of Lee's line. A final plunge through this hole would sever the Confederate army into two parts that could be destroyed in detail. "Only a few scattered handfuls of Harvey Hill's division were left," wrote Gen. William Allen, "and R. H. Anderson's was hopelessly confused and broken. . . . There was no body of Confederate infantry in this part of the field that could have resisted a serious advance." So desperate was the situation that General Longstreet himself held horses for his staff while they served two cannon supporting Hill's thin line.

But McClellan's caution stopped the breakthrough before it was born. Though Franklin's VI Corps was massed for attack, McClellan restrained it. "It would not be prudent to make the attack," he told Franklin after a brief examination of the situation, "our position on the right being . . . considerably in advance of what it had been in the morning."

On the Firing Line.

By Gilbert Gaul. Courtesy, Library

of Congress.

So McClellan turned to defensive measures. Franklin's reserve corps would not be committed, but would remain in support of the Federal right. And in the center, McClellan held back Fitz-John Porter's V Corps. After all, reasoned the Federal commander, was not this the only force that stood between the enemy and the Federal supply train on the Boonsboro Pike?

But Porter was not quite alone. The entire Federal artillery reserve stood with him. Further, Brig. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton had placed his cavalry and artillery on a commanding ridge west of the Middle Bridge during the morning. From here he had already supported the attack by Sumner's corps on the Sunken Road, and he had aided Burnside's efforts on the left. Now he stood poised for further action. Pleasonton was to wait in vain. His dual purpose of obtaining ". . . an enfilading fire upon the enemy in front of Burnside, and of enabling Sumner to advance to Sharpsburg" was nullified by McClellan's decision to halt and take the defensive.

In striking contrast to McClellan's caution, General Lee was at that very moment considering a complete envelopment of the Federal flank at the North and East Woods. By this means he might relieve the pressure on D. H. Hill; for despite the lull, Lee could not believe that McClellan had halted the attack there. If the attack in the North Woods succeeded, Lee hoped to drive the Federal remnants to the banks of Antietam Creek and administer a crushing defeat.

Jackson and J. E. B. Stuart, early in the afternoon, shifted northward and prepared to charge the Federal lines. When they arrived close to the powerful Federal artillery on Poffenberger Ridge, they saw that a Confederate attack there would be shattered by these massed guns. A wholesome respect for Federal artillerists now forced Lee to withdraw his order. As he did so, heavy firing to the south heralded a new threat developing there.

Bloody Lane

Courtesy, Library

of Congress.

|

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Mar 4 2002 10:00:00 pm PDT |